Manchurian revival

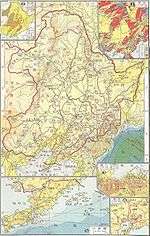

The Manchurian revival of 1908 was a Protestant revival that occurred in churches and mission stations in Manchuria (now Liaoning Province, China).

It was the first such revival to gain nationwide publicity in China as well as international repute.[1] The revival occurred during a series of half-day-long meetings led by Jonathan Goforth, a Canadian Presbyterian missionary with the Canadian Presbyterian Mission, who, along with his wife, Rosalind (Bell-Smith) Goforth went on to become the foremost missionary revivalist in early 20th century China and helped to establish revivalism as a major element of missionary work. The effect of the revivals in China reached overseas and contributed to some tension among Christian denominations in the United States, fueling the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy in the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.[2]

Beginnings

A major revival had recently taken place in Pyongyang, Korea in 1907 that involved more than 1000 people during a series of meetings where there was an emphasis of teaching on the work of the Holy Spirit. This influenced revivals in China, including the Manchurian revival of 1908.[3]

Goforth notes a fellow missionary's initial observations of the Manchurian Revival in his book, By My Spirit:

| “ | Hitherto I have had a horror of hysterics and emotionalism in religion, and the first outbursts of grief from some men who prayed displeased me exceedingly. I didn't know what was behind it all. Eventually, however, it became quite clear that nothing but the mighty Spirit of God was working in the hearts of men.[4] | ” |

Goforth arrived in Manchuria in February, 1908, but according to Goforth’s account, he ‘’…had no method. I did not know how to conduct a Revival. I could deliver an address and let the people pray, but that was all.[5]”

Shenyang

Goforth held a series of special meetings at Shenyang (Mukden), with some initial opposition from church leaders, there.

After Goforth’s address the first morning an elder stood up before all the people and confessed to having embezzled church funds. The effect on the hearers was “instantaneous”. One person gave a “piercing cry” then many, now in tears, began spontaneous prayer and confession. For three days these incidents continued. Goforth recorded, "On the fourth morning an unusually large congregation had assembled. The people seemed tense, expectant… Just then the hymn ended, and I rose to speak. All through that address I was acutely conscious of the presence of God. Concluding, I said to the people: "You may pray." Immediately a man left his seat and, with bowed head and tears streaming down his cheeks, came up to the front of the church and stood facing the congregation. It was the elder who, two days before, had given vent to that awful cry. As if impelled by some power quite beyond himself, he cried out: "I have committed adultery. I have tried three times to poison my wife." Whereupon he tore off the golden bracelets on his wrist and the gold ring from his finger and placed them on the collection plate, saying: "What have I, an elder of the Church, to do with these baubles?" Then he took out his elder's card, tore it into pieces and threw the fragments on the floor. "You people have my cards in your homes," he cried. "Kindly tear them up. I have disgraced the holy office. I herewith resign my eldership." For several minutes after this striking testimony no one stirred. Then, one after another, the entire session rose and tendered their resignations. The general burden of their confession was: "Though we have not sinned as our brother has, yet we, too, have sinned, and are unworthy to hold the sacred office any longer." Then, the deacons one by one got up and resigned from their office. "We, too, are unworthy," they confessed. For days I had noticed how the floor in front of the native pastor was wet with tears. He now rose and in broken tones said, "It is I who am to blame. If I had been what I ought to have been, this congregation would not be where it is to day. I'm not fit to be your pastor any longer. I, too, must resign." Then there followed one of the most touching scenes that I have ever witnessed. From different parts of the congregation the cry was heard: "It's all right, pastor. We appoint you to be our pastor." The cry was taken up until it seemed as if every one was endeavouring to tell the broken man standing there on the platform that their faith and confidence in him had been completely restored. There followed a call for the elders to stand up; and as the penitent leaders stood in their places, with their heads bowed, the spontaneous vote of confidence was repeated, "Elders, we appoint you to be our elders." Then came the deacons' turn. "Deacons, we appoint you to be our deacons." Thus were harmony and trust restored. That evening the elder whose confession had had such a marked effect was remonstrated with by one of his friends. "What made you go and disgrace yourself and your family like that?" he was asked. "Could I help it?" he replied.[6]"

That year hundreds of members returned to the church fellowship, many of them confessing that they did not think that they had ever really been converted before.[7]

Liaoyang

Goforth then traveled to hold a series of meetings at the Liaoyang congregation. "The revival at Liaoyang was the beginning of a movement which spread throughout the whole surrounding country. Bands of revived Christians went here and there preaching the Gospel with telling effect. At one out-station there was a Christian who had a notoriously bad son. During the meetings that were held by one of the revival bands at his village, the young man quite broken up, confessed his sins and came out strongly for Christ. His conversion produced a remarkable effect upon the whole village. Heathen would say to each other on the streets: "The Christian's God has come. Why, He has even entered that bad fellow, and driven all the badness out of him. And now he's just like other Christians. So, if you don't want to go the same way you had better keep away from that crowd." [8]"

Guangning

Goforth proceeded to Guangning (Kwangning) (near Beizhen, Liaoning) where it was told him by another missionary that, "Reports have come to us of the meetings at Mukden and Liaoyang. I thought I had better tell you, right at the beginning, that you need not expect similar results here."

After Goforth had given his sermon, he said to the people: "Please let's not have any of your ordinary kind of praying. If there are any prayers which you've got off by heart and which you've used for years, just lay them aside. We haven't any time for them. But if the Spirit of God so moves you that you feel you simply must give utterance to what is in your heart, then do not hesitate. We have time for that kind of praying. Now, the meeting is open for prayer." Spontaneous prayers come forth from several individuals at every meeting, followed by more confessions of sin and wrongdoing among church leaders.

"After the meetings, bands of revived Christians toured the surrounding country. At every out station that was visited, except one, a deep spiritual movement resulted. When the bands returned to the city this particular place was made the occasion for special prayer. Then another band was sent to the village, and a movement set on foot which quite eclipsed anything which had been seen in any of the other out stations.[9]"

Jinzhou

From the very first meeting that Goforth led at Jinzhou (Chinchow) a renewal movement began to develop. Intense prayer and anxiety to get rid of sin characterized the effect on these believer as it had done at the other mission stations.[10]

Dr. Walter Phillips, who was present at two of the meetings in Jinzhou, wrote: "It was at Chinchow that I first came into contact with the Revival. Meetings had been going on there for a week, hence, I was ushered into the heart of things unprepared, and in candour, I must add, with a strong temperamental prejudice against 'revival hysterics' in every form, so that mine is at least an unbiased witness. At once, on entering the church, one was conscious of something unusual. The place was crowded to the door, and tense, reverent attention sat on every face. The very singing was vibrant with new joy and vigour . . . The people knelt for prayer, silent at first, but soon one here and another there began to pray aloud. The voices grew and gathered volume and blended into a great wave of united supplication that swelled till it was almost a roar, and died down again into an undertone of weeping. Now I understood why the floor was so wet - it was wet with pools of tears! The very air seemed electric -- I speak in all seriousness - and strange thrills coursed up and down one's body. Then above the sobbing, in strained, choking tones, a man began to make public confession. Words of mine will fail to describe the awe and terror and pity of these confessions. It was not so much the enormity of the sins disclosed, or the depths of iniquity sounded, that shocked one. . . . It was the agony of the penitent, his groans and cries, and voice shaken with sobs; it was the sight of men forced to their feet, and, in spite of their struggles, impelled, as it seemed, to lay bare their hearts that moved one and brought the smarting tears to one's own eyes. Never have I experienced anything more heart breaking, more nerve racking than the spectacle of those souls stripped naked before their fellows. So for hour after hour it went on, till the strain was almost more than the onlooker could bear. Now it was a big, strong farmer groveling on the floor, smiting his head on the bare boards as he wailed unceasingly, 'Lord! Lord!' Now a shrinking woman in a voice scarce above a whisper, now a wee laddie from the school, with the tears streaking his piteous grimy little face, as he sobbed out: 'I cannot love my enemies. Last week I stole a farthing from my teacher. I am always fighting and cursing. I beseech the pastor, elders and deacons to pray for me.' And then again would swell that wonderful deep organ tone of united prayer. And ever as the prayer sank again the ear caught a dull undertone of quiet sobbing, of desperate entreaty from men and women, who, lost to their surroundings, were wrestling for peace.[11]"

Xinmin

The Christians in Xinmin (Shinminfu) had suffered persecution during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. 54 of the church had been killed and were considered "martyrs" for dying for their faith at the hands of the Boxers. The survivors had prepared a list, containing 250 names of those who had taken part in the massacre. It was hoped by some that revenge would one day be possible. However, after the revival meetings, the list of names was brought up to the front of the church and torn into pieces and the fragments were trampled under foot.[12]

Yingkou

Goforth ministered at Yingkou (Newchwang), the final resting-place of Scottish missionary William Chalmers Burns. Burns’ impact was still being felt 40 years later among the Christian community of Yingkou. However, the same kind of repentance and prayer broke out, here as Goforth wrote: "On entering the pulpit, I bowed as usual for a few moments in prayer. When I looked up it seemed to me as if every last man, woman and child in that church was in the throes of judgment. Tears were flowing freely, and all manner of sin was being confessed.[13]"

References

- ↑ Blumhofer, Edith Waldvogel (1993). Modern Christian Revivals. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01990-3. p.162

- ↑ Blumhofer, Edith Waldvogel (1993). Modern Christian Revivals. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01990-3. p.167

- ↑ Lee, Young-Hoon (2001). Korean Pentecost: The Great Revival of 1907. Asian Journal of Pentecostal Studies 4. p.73-76

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 1

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 3

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 3

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 3

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 3

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 4

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 4

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 4

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 4

- ↑ Goforth, Jonathan (1929). By My Spirit. Evangel Publishing House. ISBN 1-928915-65-5. ch. 4

Bibliography

- Rosalind Goforth,Goforth of China; McClelland and Stewart, (1937), Bethany House, 1986.

- Rosalind Goforth, How I Know God Answers Prayer (1921), Zondervan.

- Ruth A. Tucker, From Jerusalem to Iriyan Jaya; A Biographical History of Christian Missions; 1983, Zondervan.

- By My Spirit (1929, 1942, 1964, 1983)

- Rosalind Goforth, Chinese Diamonds for the King of Kings (1920, 1945)

- Alvyn Austin, Saving China: Canadian Missionaries in the Middle Kingdom, 1888-1959 (1986), chaps. 2, 6

- Daniel H. Bays, Christian Revival in China, 1900-1937

- Edith L. Blumhofer and Randall Balmer, eds., Modern Christian Revivals (1993)

- James Webster, Times of Blessing in Manchuria (1908)

- "Revival in Manchuria," p. 4; published by the Presbyterian Church in Ireland.