Mamoru Oshii

| Mamoru Oshii | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Mamoru Oshii introduces his work NEC Sky Crawlers, in 2008 | |

| Native name | 押井守 |

| Born |

Mamoru Oshii August 8, 1951 Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | Film director, screenwriter, manga writer, television director, novelist |

| Years active | 1977–present |

| Part of a series on |

| Anime and manga |

|---|

|

|

Selected biographies |

|

|

|

General |

|

|

Mamoru Oshii (押井 守 Oshii Mamoru, born August 8, 1951) is a Japanese filmmaker, television director and screenwriter. Famous for his philosophy-oriented storytelling, Oshii has directed a number of popular anime, including Urusei Yatsura, Ghost in the Shell, and Patlabor 2: The Movie. He also holds the distinction of having created the first ever OVA, Dallos. For his work, Oshii has received and been nominated for numerous awards, including the Palme d'Or and Golden Lion. He has also attracted praise from international directors such as James Cameron and The Wachowskis.

Currently, Oshii lives in Atami, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan with his dog – a mutt named Daniel.[1]

Career

Early career (1977–1982)

As a student, Mamoru Oshii was fascinated by the film La jetée by Chris Marker.[2] He also repeatedly watched European cinema, such as films by Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Jean-Pierre Melville.[3] These filmmakers, together with Jean-Luc Godard, Andrei Tarkovsky and Jerzy Kawalerowicz,[4] would later serve as influences for Oshii's own cinematic career.[5]

In 1976, he graduated from Tokyo Gakugei University. The following year, he entered Tatsunoko Productions and worked on his first anime as a storyboard artist on Ippatsu Kanta-kun.[6] During this period at Tatsunoko, Oshii worked on many anime as a storyboard artist, most of which were part of the Time Bokan television series. In 1980, he moved to Studio Pierrot under the supervision of his mentor, Hisayuki Toriumi.[6]

Success with Urusei Yatsura (1981–1984)

Mamoru Oshii's work as director and storyboard artist of the animated Urusei Yatsura TV series brought him into the spotlight. Following its success, he directed two Urusei Yatsura films: Urusei Yatsura: Only You (1983) and Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer (1984). While the first film, though an original story, continued much in the spirit of the series, Beautiful Dreamer (which was also written by Oshii with no consultation from Takahashi)[7] was a significant departure and an early example of his now contemporary style.[8]

Dallos, Angel's Egg and Anchor (1983–1985)

In the midst of his work with Studio Pierrot, Oshii took on independent work and directed the first OVA, Dallos, in 1983. In 1984, Oshii left Studio Pierrot.[9] Moving to Studio Deen, he wrote and directed Angel's Egg (1985), a surreal film rich with Biblical symbolism, featuring the character designs of Yoshitaka Amano. The producer of the film, Toshio Suzuki, later founded the renowned Studio Ghibli with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.[10] Following the release of the film, Miyazaki and Takahata began collaborating with Mamoru Oshii on his next film, Anchor. The film was canceled early in the initial planning stages when the trio had artistic disagreements.[11][12] Despite their differences, Toshio Suzuki and Studio Ghibli would later help Oshii with his production of Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004).[13] To this day, Oshii maintains skeptical, but respectful, views of each of Takahata and Miyazaki's films. Though he has been critical of Miyazaki's attitude towards his workers, he also claims that he would feel "strangely empty" and "it would be boring" if both Miyazaki and Takahata stopped making films.[14]

Patlabor and live-action (1987–1993)

In the late 1980s, Oshii was solicited by his friend Kazunori Itō to join Headgear as a director. The group was composed of Kazunori Itō (screenwriter), Masami Yuki (manga artist), Yutaka Izubuchi (mechanical designer), Akemi Takada (character designer) and Mamoru Oshii (director).[15][16] Together they were responsible for the Patlabor TV series, OVA, and films. Released in the midst of Japan's economic crisis, the Patlabor series and films projected a dynamic near-future world in which grave social crisis and ecological challenges were overcome by technological ingenuity, and were a big success in the mecha genre.

Between production of the Patlabor movies/series, Oshii delved into live-action for the first time, releasing his first non-animated film, The Red Spectacles (1987). This led to another live-action work titled Stray Dog: Kerberos Panzer Cops (1991); both films are part of Oshii's ongoing Kerberos saga. Following Stray Dog Oshii made yet another live-action film, Talking Head (1992), which is a surreal look at his view on film.

Recent career (1995–present)

In 1995, Mamoru Oshii released his landmark animated cyberpunk film, Ghost in the Shell, in Japan, the United States, and Europe. It hit the top of the US Billboard video charts in 1996, the first anime video ever to do so.[2][17] Concerning a female cyborg desperate to find the meaning of her existence, the film was a critical success and is widely regarded to be a masterpiece and anime classic.

After a 5-year hiatus from directing to work on other projects, Oshii returned to live-action with the Japanese-Polish feature Avalon (2001), which was selected for an out of competition screening at the Cannes Film Festival. His next animated feature film was the long-awaited sequel to Ghost in the Shell, titled Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence. Four years in the making, the film focuses on Batou as he investigates a series of gruesome murders, while trying to reconcile with his deteriorating humanity. Though it received mixed reviews, Innocence was selected to compete at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival[18] for the coveted Palme d'Or prize, making it the first (and thus far, only) anime to be so honored.[19]

Oshii was approached to be one of the directors of The Animatrix, but he was unable to participate because of his work in Innocence.[20] Following Innocence, Oshii also contemplated directing a segment for the anthology film Paris, je t'aime, but ultimately declined the offer.[5] Meanwhile, in 2005, there were talks of a Kenta Fukasaku and Oshii collaboration. It was announced that Oshii would write the script for a film titled Elle is Burning, as well as provide CGI consultation, while Fukasaku would direct.[21][22] Although Oshii completed the script, the film was ultimately shelved because, among other problems, the large budget it would require.[23]

His next film, The Sky Crawlers (2008), competed for the Golden Lion in the Venice Film Festival. In the film, Oshii posits an alternate history in which war has been privatised; children are manufactured and sent to aerial battles which are exploited for commercial entertainment. Subsequent to The Sky Crawlers, Oshii wrote the screenplay to the Production I.G film Musashi: The Dream of the Last Samurai, which has been described as possibly the first ever anime documentary.[24] In 2009, he wrote and directed the live-action feature Assault Girls and served as creative director for the Production I.G-produced segment of the animated short film anthology Halo Legends. In 2010, Oshii announced his next film will be an adaptation of Mitsuteru Yokoyama's Tetsujin-28 manga.[25] The Tetsujin-28 project turned out to be a live action film called '28 1/2'.[26]

In 2012, Oshii announced that he was working on a new live-action film. He will be writing and directing the military science-fiction thriller Garm Wars: The Last Druid.[27] The film's trailer was released in September 2014,[28] and the premiere screening was held the following month at the 27th Tokyo International Film Festival.[29]

He followed with the live-action film Tōkyō Mukokuseki Shōjo, a suspense thriller released in July 2015.[30]

Style

Oshii has stated his approach to directing is in direct contrast to what he perceives to be the Hollywood formula, i.e. he regards the visuals as the most important aspect, followed by the story and the characters come last. He also notes that his main motivation in making films is to "create worlds different from our own."[31]

Mamoru Oshii's films typically open with an action sequence. Thereafter, the film usually follows a much slower rhythm punctuated by several sequences of fast action. Oshii also frequently inserts a montage sequence in each of his movies, typically two-minutes long, muted of dialogue and set against the backdrop of Kenji Kawai's music.[32] Recurrent imagery include reflections/mirrors,[33] flocks of birds,[34][35] and basset hounds similar to his own.[34][36] The basset hound was seen most prominently in Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence,[36] and was a major plot point in his live-action film, Avalon. The Mauser C96 also appears periodically in his films.[37]

Oshii is especially noted for how he significantly strays from the source material his films are based on, notably in his adaptations of Urusei Yatsura, Patlabor, and Ghost in the Shell. In their original manga versions, these three titles exhibited a mood that was more along the lines of frantic slapstick comedy (Urusei Yatsura) or convivial dramedy (Patlabor, Ghost in the Shell). Oshii, in adapting the works created a slower, more dark atmosphere especially noticeable in Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer and Patlabor 2: The Movie. For the Ghost in the Shell movie, Oshii elected to leave out the humor and character banter of Masamune Shirow's original manga.

"Oshii's work... steers clear of such stereotypes in both image and sexual orientation," wrote Andrez Bergen in an article on Oshii that appeared in Japan's Daily Yomiuri newspaper in 2004. "His movies are dark, thought-provoking, minimalist diatribes with an underlying complexity; at the same time he pushes the perimeters of technology when it comes to the medium itself. Character design plays equitable importance."[3]

Oshii also wrote and directed several animated movies and live-action films based on his personal world view, influenced by the anti-AMPO student movements of the 1960s and 1970s in which he participated.[38] The anti-AMPO student movements were protests during 1960s Japan against the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan. The first film to touch on this political background was the live-action film The Red Spectacles. This film, set in the same world as the Oshii-scripted film Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (1999), is about a former member of the special unit of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Force dealing with a fascist government.

Influence

The Wachowskis are known to have been impressed with Ghost in the Shell and went as far as to screen it to producer Joel Silver to show him what kind of film they wanted to make for The Matrix.[39][40] Indeed, various scenes from Ghost in the Shell have been seemingly lifted and transposed in The Matrix.[41][42] Ghost in the Shell was also the chief inspiration for the video game Oni.[43]

Kenji Kamiyama, the director of the Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex television series, considers Oshii his mentor,[44] and states that he tried to copy Oshii's entire style when creating the Stand Alone Complex series, believing that audiences would be tricked into thinking Oshii had directed the series.[45]

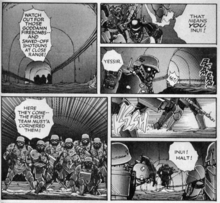

Many have also noted the similarities in the Helghast design from the Killzone series of video games to the Kerberos Panzer Protect Gear, first seen in the 1987 film The Red Spectacles. Asked of these observations, Guerrilla Games, video game developer for the Killzone series, did not address the similarities. The developers contend the Helghast design was inspired by the gas masks of World War I,[46] though this does not account for the similarity in the glowing red/orange eyes between the two designs.

James Cameron is another filmmaker who has voiced his admiration for Oshii, stating at one point that Avalon was "the most artistic, beautiful and stylish sci-fi film."[47] He also praised Ghost in the Shell, stating it was "the first truly adult animation film to reach a level of literary and visual excellence."[48]

Oshii appeared in the 2013 documentary film, Rewind This! about the impact of VHS on the film industry and home video. He also recently had a get-together with Duncan Jones.[49]

Collaboration

Mamoru Oshii has worked extensively with Production I.G. Every animated film he has made since Patlabor: The Movie (1989) has been produced under the studio. He also worked closely with screenwriter Kazunori Itō; they made five films together, beginning with The Red Spectacles and ending with Avalon. His closest colleague, however, is music composer Kenji Kawai. Kawai has composed most of the music in Oshii's work, including ten of his feature films. According to Oshii, "Kenji Kawai's music is responsible for 50 percent of [his] films' successes" and he "can't do anything without [Kenji Kawai]."[50]

Kerberos saga

1980s

The Kerberos saga is Mamoru Oshii's lifework, created in 1986.[51] A military science fiction franchise and alternate history universe, it spans all media and has lasted for more than 20 years since his January 1987 radio drama While Waiting for the Red Spectacles. In 1987, Oshii released The Red Spectacles, his first live-action feature and the first Kerberos saga film. The manga adaptation, Kerberos Panzer Cop, written by Mamoru Oshii and illustrated by Kamui Fujiwara, was serialized in 1988 until 1990.

1990s

Acts 1~4 of Kerberos Panzer Cop was compiled in 1990 as a single volume. In 1991, the live-action film adaptation of the tankōbon was released as StrayDog Kerberos Panzer Cops. In 1999, the Oshii-scripted Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade, the anime feature film adaptation of the manga's first volume, was directed by Oshii's collaborator Hiroyuki Okiura, and was released in International Film Festivals starting in France.[52]

2000s

In 2000, the second part of the manga (Acts 5~8) was serialized, then published and compiled as a second volume. After the manga's completion and publishing as volumes 1 and 2, Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade was finally released in Japan during the same year.[53] In 2003, Kerberos Panzer Cop's sequel, Kerberos Saga Rainy Dogs was serialized, then compiled as a single volume in 2005. In 2006 Kerberos Panzer Jäger was broadcast in Japan as a 20-year celebration of the saga. The same year, Oshii revealed his plan to release an anime/3DCG adaptation film of the drama in 2009, the Kerberos Panzer Blitzkrieg project.[51] But, there are many sources on the Internet revealed that the project was canceled long time ago. As there are no sources or the news on the Internet on the project, one of the sources revealed that Oshii has canceled the project in year 2010, circa March. Many fans of Kerberos Saga were outraged and disappointed after learning the cancellation of the project. There are also many sources which revealed the reasons that lead to the cancellation of the project. Despite that, the fans of Kerberos Saga assumed and believed that the reasons are not reasonable and "just another pile of rubbish"(according to the fans) to justify the decision of cancelling the project. In late 2006, Oshii launched a Kerberos saga crossover manga series titled Kerberos & Tachiguishi.

Other work

In addition to his directing work, Oshii is a prolific screenwriter and author of manga and novels. As well as writing the Kerberos series of manga, Oshii wrote the script for the manga Seraphim 266,613,336 Wings originally illustrated by Satoshi Kon.[54] Their collaboration was difficult due to artistic differences over the development of the story and Seraphim was not completed.[55] Part one was serialised in 16 instalments in the May 1994 through November 1995 issues of monthly Animage. Following Satoshi Kon's death in 2010 it was partially reissued in a special memorial supplement of Monthly Comic Ryū and published in comic book form the same year.[56][57][58] Oshii has since worked on a Seraphim Prologue, the Three Wise Men's Worship Volume, with illustrations by Katsuya Terada, released by Tokuma Shoten as an other Ryū supplement.[59] Oshii also wrote the screenplay of Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade[60] and is credited as a co-planner for Blood: The Last Vampire (2000)[61] and Blood+.[62] Oshii is also credited as providing "story concept" for Ghost in the Shell: S.A.C. 2nd GIG, though he asserts he was tasked to supervise and provide the plots for all 26 episodes of the series.[5] In 2005 Oshii served as supervisor for the Mobile Police Patlabor Comes Back: MiniPato video game.[63] In 2008, he again served as special consultant for the development of a video game, The Sky Crawlers: Innocent Aces.

Awards and nominations

- 1996: Feature Film Award (Ghost in the Shell)[64]

- 2004: Feature Film Award (Ghost in the Shell: Innocence)[64]

- 2004: Nominated for Palme d'Or (Ghost in the Shell: Innocence)[65]

- 2002: Best Feature Film (Avalon)[66]

- 1993: Best Animated Film (Patlabor 2: The Movie)[67]

- 2008: Best Animated Film (The Sky Crawlers)[68]

- 2004: 25th Nihon SF Taisho Award (Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence)[69]

Sitges - Catalonian International Film Festival:

- 2004: Orient Express Award (Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence)[70]

- 2008: Nominated for Golden Lion (The Sky Crawlers)[71]

- 2008: Future Film Festival Digital Award (The Sky Crawlers)[72]

Filmography

Notes

- ↑ "Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence - The Creators". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- 1 2 Wah Lau, Jenny Kwok (2003). Multiple Modernities: Cinemas and Popular Media in Transcultural East Asia. Temple University Press. p. 78. ISBN 1-56639-986-6.

- 1 2 Bergen, Andrez (March 2004). "The Age of Innocence". Daily Yomiuri.

- ↑ "Midnight Eye interview: Mamorou Oshii". Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- 1 2 3 "THERE IS NO APHRODISIAC LIKE INNOCENCE". Archived from the original on 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- 1 2 Ruh, Brian (2004). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 1-4039-6334-7.

- ↑ Mamoru Oshii commentary in U.S. Manga Corps DVD release of Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer

- ↑ Ruh, Brian (2004). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 1-4039-6334-7.

- ↑ Ruh, Brian (2004). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 6. ISBN 1-4039-6334-7.

- ↑ "Who's Who // Nausicaa.net". Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ Ruh, Brian (2004). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 59, 60. ISBN 1-4039-6334-7.

- ↑ "Oshii on Miyazaki and Takahata // Hayao Miyazaki Web". Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ "Toshio Suzuki - IMDB Profile". Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ "Oshii on Miyazaki and Takahata". Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ↑ Ruh, Brian (2004). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 74, 76. ISBN 1-4039-6334-7.

- ↑ "Headgear". Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ "Ghost in the Shell taking the World by Storm". Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ "GHOST IN THE SHELL 2: INNOCENCE invited to compete at this year's CANNES INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL" (Press release). About.com. 2004-05-02. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ↑ "Interviewing the Animatrix, Part 1". Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ↑ "KENTA FUKASAKUS' 'ERU NO RAN' SCREENPLAY & CGI BY MAMORU OSHII.". Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ↑ "SOME DETAILS ON THE OSHII / FUKASAKU COLLABORATION ELLE IS BURNING". Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ↑ "Hopes for Fukasaku + Oshii collaboration still burning faintly". Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ↑ "Musashi: The Dream of the Last Samurai - San Francisco Film Society". Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- ↑ "Ghost in the Shell's Oshii Announces Tetsujin 28 Film (Updated)". Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ↑ "28 1/2 official site". Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ↑ "Ghost in the Shell Director Mamoru Oshii Trades Cyberpunk for Steampunk in The Last Druid: Garm Wars". Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- ↑ "Watch The Trailer For Oshii's Live Action GARM WARS: THE LAST DRUID". Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- ↑ "Special Screenings: GARM WARS The Last Druid". Retrieved 2014-11-28.

- ↑ "Mamoru Oshii Makes Live-Action Thriller Tōkyō Mukokuseki Shōjo". Anime News Network. April 30, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ Nelmes, Jill (2007). Introduction to Film Studies. Routledge. pp. 228, 229. ISBN 0-415-40929-2.

- ↑ "senses of cinema - Mamoru Oshii". Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- ↑ Lunning, Frenchy (2006). Mechademia 1: Emerging Worlds of Anime and Manga. Univ Of Minnesota Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-8166-4945-6.

- 1 2 "Mamoru Oshii A.V. Club Interview". Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- ↑ "Miyazaki vs Oshii around Patlabor 2 // Hayao Miyazaki Web". Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- 1 2 "Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence - The Inspiration". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "C96 Broomhandle Mauser in Films & TV". Retrieved 2009-05-24.

- ↑ Ruh, Brian (2004). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 80. ISBN 1-4039-6334-7.

- ↑ Joel Silver, interviewed in "Scrolls to Screen: A Brief History of Anime" featurette on The Animatrix DVD.

- ↑ Joel Silver, interviewed in "Making The Matrix" featurette on The Matrix DVD.

- ↑ "A Matrix & Ghost in the Shell Comparison". Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ↑ "Scrolls to Screen: A Brief History of Anime" featurette on The Animatrix DVD

- ↑ "Interview with lead engineer Brent Pease". Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ↑ "Behind the Scenes Part 10: Kenji Kamiyama (Director)". Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- ↑ "Interview: Kenji Kamiyama". Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- ↑ "Guerrilla Games of Killzone (Guerrilla Games/Sony) Interview". Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ↑ DVD cover of Miramax release of Avalon

- ↑ "Manga.com - Ghost in the Shell". Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- ↑ http://ro69.jp/blog/cut/59186

- ↑ "The Japan Times Online Interview". Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- 1 2 押井守の「ケルベロス」最新作はラジオドラマ (in Japanese). Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ Beck, Jerry (2005). The Animated Movie Guide. Chicago Review Press. p. 130. ISBN 1-55652-591-5.

- ↑ "Production I.G> Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade> OVERVIEW". Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ Amano, Masanao (2004). Manga Design. Taschen. p. 228. ISBN 3-8228-2591-3.

- ↑ "Kon's Tone Unreleased Comic" (in Japanese). Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Kon's Tone 月刊COMICリュウ 12月号" [Kon's Tone December issue Monthly Comic Ryū] (in Japanese). October 19, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Satoshi Kon's Seraphim, Opus Manga Reprinted". Anime News Network. December 8, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ Oshii, Mamoru; Kon, Satoshi (December 4, 2014). セラフィム 2億6661万3336の翼 [Seraphim: 266,613,336 Wings] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten. p. 231. ISBN 978-4-19-950220-0. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ Terada, Katsuya (April 10, 2013). 寺田克也 ココ10年 [Tetsuya Terada 10 Ten - 10 Year Retrospective] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Pie International. p. 250. ISBN 978-4-7562-4376-8. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Production I.G > Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade> STAFF & CAST". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Production I.G > Blood: The Last Vampire> STAFF & CAST". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Production I.G > BLOOD+> STAFF & CAST". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Production I.G > Mobile Police Patlabor Comes Back: MiniPato> STAFF & CAST". Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- 1 2 これまでの記録 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes - Official Selection 2004". Festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "SCI-FI-London film festival 1-3 Feb 2002". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ 毎日映画コンクール 歴代受賞作品 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2005-03-06. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Production I.G - The Sky is Best Animated Feature Film at the 63rd Mainichi Film Awards". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "25th Nihon SF Grand Prize announced (December 4, 2004)". Jlit.net. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Sitges Previous Editions - 37 edition. 2004". Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ↑ "Production I.G - The Sky Crawlers in Competition at the 65th Venice Film Festival". Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ "Oshii's Sky Crawlers Wins Venice Fest's Digital Award". Retrieved 2009-06-12.

References

- Ruh, Brian (2004). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6334-7.

- Mamoru Oshii -- Senses of Cinema: Great Directors Critical Database

- Production I.G

- TheBassetHound.net - A Mamoru Oshii Fansite

Further reading

- Cavallaro, Dani (2006). Cinema of Mamoru Oshii: Fantasy, Technology and Politics. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2764-7.

- Ruh, Brian (2014). Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii. Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9781137437891.

External links

- Mamoru Oshii Official Site (Japanese)

- Mamoru Oshii at the Internet Movie Database

- Mamoru Oshii at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- The Straydog Fansite (Japanese)