Malacañang Palace

| Malacañan Palace | |

|---|---|

| Palasyo ng Malakanyang (Filipino) | |

|

Malacañan Palace as viewed from the Pasig River. | |

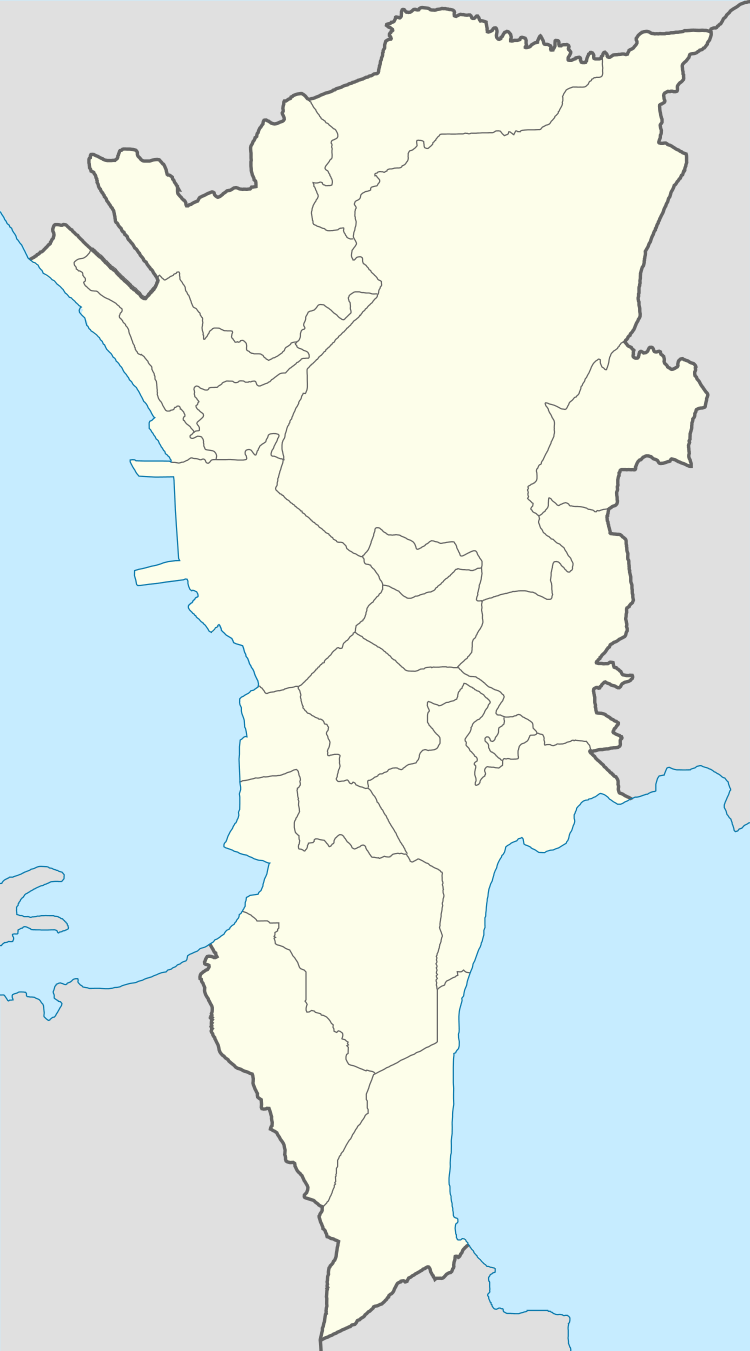

Location in Metro Manila | |

| Former names |

Palacio de Malacañan Palacio de Malacañán |

| Alternative names | Malacañan Palace (official) |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Spanish colonial architecture, Neo-classical architecture |

| Location | San Miguel, Manila |

| Address |

José P. Laurel Street, San Miguel, Manila |

| Country | Philippines |

| Coordinates | 14°35′38″N 120°59′40″E / 14.5939°N 120.9945°ECoordinates: 14°35′38″N 120°59′40″E / 14.5939°N 120.9945°E |

| Current tenants |

Rodrigo R. Duterte President of the Philippines |

| Construction started | 1750[1] |

Malacañang Palace (officially Malacañan Palace, colloquially "Malacañang"; Filipino: Palasyo ng Malakanyang [malakɐˈɲaŋ], Spanish: Palacio de Malacañan [pala'sjo 'de malakaˈɲaŋ]) is the official residence and principal workplace of the President of the Philippines located in the capital city of Manila. The Palace is in fact a complex of buildings built largely in Spanish colonial and Neo-classical style. Under the current administration, President Rodrigo Duterte wants to rename Malacañang to Peoples' Palace.[2]

The original structure was built in 1750 by Don Luís Rocha as a summer house along the Pasig River. It was purchased by the state in 1825 as the summer residence for the Spanish Governor-General. After the June 3, 1863 earthquake destroyed the Palacio del Gobernador (Governor's Palace) in the walled city of Manila, it became the Governor-General's official residence. After sovereignty over the Islands was ceded to the United States in 1898, it became the residence of the American Governors, with General Wesley Merritt being the first.[3]

Since 1863, the Palace has been occupied by eighteen Spanish Governors-General, fourteen American Military and Civil Governors, and later the Presidents of the Philippines.[3] The Palace had been enlarged and refurbished several times since 1750; the grounds were expanded to include neighboring estates, and many buildings were demolished and constructed during the Spanish and American periods. Most recently, the Palace complex was again drastically remodeled and extensively rebuilt during the term of Ferdinand Marcos.[4] Among the presidents of the present Fifth Republic, only Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo has actually lived in the main Palace, with all others residing in nearby properties that form part of the larger Palace complex.[4]

The Palace has been seized several times as the result of protests starting with the People Power Revolution, the 1989 coup attempt (when the Palace was buzzed by T-28 Trojans); the 2001 Manila riots; and the EDSA III or May 1 riots.

Etymology

Whence "Malacañang"?

Place names often provide a valuable and sometimes colorful window on the past, preserving how earlier generations perceived a locality as distinct and noteworthy as a point of reference.

Filipino geography is especially rich and evocative with such names as – to take one common form found around Manila – Meycauayan (“there is bamboo,” a town in Bulacan province), Maysantol (“there are santol fruit trees,” a part of the city of Pasig), Maybunga (“there is fruit,” also part of Pasig) and the origin of Manila itself: Maynilad (“there are nilad plants”). There are also places such as Pulanglupa (“red earth,” a part of the city of Las Piñas) and the now defunct Malapad-na-bato (“broad rock,” at Guadalupe in the city of Makati). Further examples abound.

If scholars are to be believed, “Malacañan” – a small area by the Pasig River – is also just such a name, but with a less obvious origin that has prompted different etymological explanations since the 19th century. There are four possibilities, all evoking something different.

Malacañan as a Place of Work

The earliest explanation was given by the Spanish historian Felipe de Govantes in his 1877 Compendio de la Historia de Filipinas, and gives an echo of occupational life. Govantes wrote that “…Malacañan quiere decir en castellano, sitio del pescador” (Malacañan in Spanish means place of the fisherman) . This was repeated in the 1895 Historia general de Filipinas by José Montero y Vidal and the Historia de Filipinas by Manuel Artigas y Cuerva in 1916 . In 1972, Ileana Maramag in her work on Malacañan history supplied the Tagalog word: mamalakáya, or fisherman. On this view then, the name was originally something like Mamalakáya-han – with the addition of the Tagalog suffix for “place of,” and must have been later simplified and Hispanized as “Malacañan”.

Malacañan as a Site of Worship

In the mid-1930s, the Assistant Director of the National Library, Eulogio Rodriguez wrote an undated letter to William Teahan, who was an advisor (as well as brother-in-law) to the then American Governor General, Frank Murphy. Drawing from unfortunately unknown sources, Rodriguez stated that “Malacañan” had two possible derivations: the Tagalog ma lakán iyán, meaning “a place of many great ones,” or the Spanish mala caña, or “evil bamboo” or “evil cane”.

These two alternative explanations are actually related in their general basis. The thick groves of bamboo that were most likely abundant at Malacañan in earlier times would have been typically regarded by pre-evangelized Filipinos (and by more than a few even to this day) as the dwelling place of powerful spirits, or nuno. Other dwelling places would have been the streams and large Calumpang trees also profuse in the area. The “great ones” referred to were almost certainly these spirits, rather than actual living people, and therefore “Malacañan” by this version truly evokes a central element of early Filipino civilization: the often delicate relationship between people and the environment around them, populated as it was with forces that could undo a man’s labors and fortune. The appeasement of such “great ones” was an important part of Filipino religiosity, and the evangelizing missionaries were much concerned with stamping out these and other “pagan” practices.

While ma lakán iyán, or a similar oft-proposed variant may lakán diyán, meaning “there are great ones there” in its acknowledgement of powerful spirits among the dense bamboo, prompts respect and then perhaps fear, the other possibility that Rodriguez proposed suggests something wholly negative. Mala caña may reasonably have been coined by proselytizing friars as part of their efforts to have parishioners look more to the gospels and the one true faith rather than to such a malacañang lugar or “place of evil bamboo.”

Malacañan as the Home of a ‘Big Man’

The Rocha family cherish a legend that would have the word “Malacañan” as directly attributable to Luis Rocha himself. In a 1972 interview conducted by Ileana Maramag, Antonio Rocha related that his illustrious ancestor would take siesta in the house that he had built and that the Sikh watchman would hush noisy passers-by. Malakí iyán or “he is a big man” he would say, gesturing towards the house at the sleeping tycoon who would not be amused at being prematurely roused. In this way, the house and its immediate area came to be named.

Malacañan as a Reference from the Waterway

A glance at a map is suggestive of a fourth possibility. Malacañan is on the right bank of the Pasig River, and there is a Tagalog word referring to “of the right,” which is malakánan. But so what? The river is somewhat long and meandering, with a correspondingly lengthy right bank. However, the river at Malacañan divides around the Isla de Convalecencia as it does nowhere else along its course. Hence, the need to make a distinction between left and right would seem to be most relevant at this very place. Perhaps then, Malacañan’s origin is as a point of reference in the lively and ancient traffic on the water of the Pasig river.

In the end, there is no conclusive evidence that points one way or another to the true origin of the name of Malacañan. The area was swampy, insalubrious, and hence uninhabited. But it could have been a good fishing spot (if not actually the home of a fishermen) and almost certainly was perceived – precisely because of its marshy, unhealthy, bamboo-teeming riverbank, as an abode of many nuno. The Rocha derivation sounds whimsical, but even treating it as a serious possibility, personality-conscious Filipinos would surely have remembered in their local traditions the formidable caballero who had lived so largely in their midst in the second half of the 18th century. And finally, Malacañan as a landmark for riverine life, while intuitively appealing, is pure speculation. Given everything, the derivation of Malacañan as “Place of the Fisherman,” has the advantage of being put forward at a much earlier and different time – in the 1870s – when economic development had only just started and oral traditions would have perhaps been more intact.[5]

In current political and common parlance, "Malacañang" and "the Palace" has become metonyms for the Presidency, the executive branch, and by extension, the national government as a whole.

Spelling

Whatever the origin, the word Malacañang is indisputably Tagalog. During the Spanish Colonial Era, Spanish language books published during the era spelled the word as Malacañang (not Malacañán).[7][8][9][10] Early Spanish plans for the palace spell the name as Malacañang.[11] The name was allegedly changed to "Malacañan" during the American occupation of the Philippines from 1898 until 1946, despite the fact that "-ng" as a final sound is very familiar in the English language.[12] However, after the inauguration of President Ramon Magsaysay on December 30, 1953, the Philippine government changed the name to Malacañang: Residence of the President of the Philippines in honor of Palace's historical roots.[12]

During the administration of President Corazon Aquino, for historical reasons, government policy has been to make the distinction between "Malacañan Palace", official residence of the President and "Malacañang", Office of the President. The restoration of the designation "Malacañan Palace" was reflected in official stationery, and signage, including the often seen backdrop in the press room modeled after the White House sign.[6] In practice, the heading Malacañan Palace is reserved for official documents personally signed by the President, while those delegated to and signed by subordinates use the heading Malacañang.

History

Spanish colonial era

The Spanish Captains-General (before the independence of New Spain, from which the Philippines was directly governed) and the later Governors-General originally resided at the Palacio del Gobernador (Governor's Palace) fronting the city square in the walled city of Intramuros in Manila. Malacañan Palace was originally built as a casita (or country house) in 1750 – made of adobe, wood, with interiors panelled with finest narra and molave. It sits in a 16 hectare land owned by Spanish aristocrat Don Antonio V. Rocha. It was subsequently sold to Col. José Miguel Formento in November 16, 1802 for a sum of thousand pesos. Later it was sold to the government upon his death in January 1825. It became the temporary summer residence of the Governors-General when the heat became unbearable in Intramuros with its gardens and a verandah along the wide river.[8]

Rafael de Echague y Berminghan, previously Governor of Puerto Rico, became the first Spanish Governor-General to reside in the Palace. Finding the place too small, a wooden two-story building was added to the back of the original structure, as well as smaller buildings for aides, guards and porters, as well as stables, carriage sheds and a boat landing for river-borne visitors. Between 1875 and 1879, reconstruction and expansion resumed after the Palace was hit by more earthquakes, typhoons and fire. An 1869 earthquake hit Malacañang, thus, repairs are made urgent. Posts and supports were repaired or replaced. Balconies are reinforced. Cornices are provided for the roof. Roofing was replaced with G.I. roofing (formerly tile roofs) to lighten loads to the walls. The interior was refurbished. By the end of Spanish rule in 1898, Malacañan Palace was a rambling complex of mostly wooden buildings that had sliding capiz windows, patios and azoteas.[4]

In 1880, an earthquake occurred again. Porticos were added to the facade to shelter waiting carriages. In 1885, the flagpole was installed in front of the palace. Decaying woodwork, stuck shell windows, leaking roofs, loose kitchen tiles, drooped stables – these are some of the reflected deterioration due to numerous natural phenomena. A total of Php 22,000 was spent for renovation and reconstruction.

American colonial rule

When the Philippines came under the American sovereignty following the Spanish–American War, Malacañan Palace became the residence of the American Governor-General. Gen. Wesley Merritt became the first American Military Governor to reside at the Palace in 1898, while William Howard Taft became the first Civil Governor resident in 1901.[3] They continued to improve and enlarge the Palace, buying more land and reclaiming more of the Pasig River. From 1875 up to 1879, renovations were conducted. Left and right wings were added. An azotea facing the river was joined to the existing azotea. A staircase was transferred to the center of the foyer; and galleries were built around the stairway where the public could circulate during crowded receptions. Ground level was raised above the flood line, replacing wood with concrete, and beautifying the interiors with hardwood panelling and adding magnificent chandeliers.[4]

Commonwealth Era

The complex became residence of the President of the Philippines upon the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines on November 15, 1935. President Manuel L. Quezon became the first Filipino resident of the Palace. It has been the Philippine President's official residence ever since. One major improvement addressed with American Period was solution to flood control. He tackled the flooding problem around Malacañang by reclaiming 15 feet of the Pasig River Bank and building a concrete wall. He also converted the ground floor (bodega) into a social hall. In addition to that, Americans use shutters alike of Japanese shoji (made of opalescent shell) to soften intensity of tropic sunlight.

Emilio Aguinaldo, recognized as the first Filipino president but of the revolutionary government, the First Philippine Republic, established during the Spanish rule. He did not reside but was later taken to the Palace by the Americans as a political prisoner for a few weeks in 1901 after his capture in Palanan, Isabela. He resided in his private home as president, now the Aguinaldo Shrine, in Kawit, Cavite.

Malacañan Palace survived the Second World War, the only major government building left standing after the Bombing of Manila. Only the southwest side of the Palace—which would have been the State Dining Room and its service area—was damaged by shelling.[4] During the Second World War, in 1942, Japanese turned Malacañang into a gilded prison. Quezon moved his seat to Corregidor, the headquarters of General Douglas MacArthur.

Efforts of Macapagal

By the time former President Diosdado Macapagal moved to the palace, it was in need of immense repair and restoration works. First Lady Mrs. Eva Macapagal initiated a massive beautification project which drove sidewalk vendors away from the grounds and turned muddy areas to landscaped gardens.

Sovereign Philippines

The longest residents of the Palace were President Ferdinand Marcos and his wife, Imelda, who resided there from December 1965 to February 1986. Following a student uprising that nearly breached the Palace gates in the early 1970s, Martial Law was declared, and the Palace complex and its surrounding neighbourhood was closed to the public.

The Pasig River, cleaner in the 19th century, had developed a foul odour in the 1970s and became a breeding ground for mosquitoes. Between 1978–79, Mrs. Marcos oversaw the reconstruction of the Palace to her own extravagant tastes. The Palace was expanded with the façades on all four sides moved forward. The Presidential quarters were enlarged on the front along J.P. Laurel, destroying the small garden and driveway leading to the private entrance, while a new dining room and expanded guest suites were built on the main entrance front. On the side facing the river, the Ceremonial Hall was built to replace the azoteas, veranda and pavilion. A larger Presidential Bedroom was constructed on the remaining side, with a disco at roof level. The layout of the old rooms was retained, although the rooms themselves were enlarged and new bedroom suites inserted in what had been part of the garden.[4]

The old Palace was gutted almost entirely, not only to meet the needs of the Presidential Family, but also because the buildings had been weakened by patch up renovations over a century that had resulted in unstable floors and leaking roofs. The building is now made of poured concrete, concrete slabs, steel girders and trusses, all concealed under elegant hardwood floors, panels and ceilings. It is fully bullet-proofed, cooled by central air-conditioning with filters, and has an independent power supply. Architect Jorge Ramos oversaw the reconstruction, which was closely supervised by Mrs. Marcos. The refurbished Palace was inaugurated on May 1, 1979–the Marcos' silver wedding anniversary.[4]

Several changes were implemented to beautify the Malacañan Palace. The servants' quarters building was transformed—what we know today as the Premier Guest House. The veranda overlooking Pasig River was walled up to become the new Maharlika Hall. Across the river, a guest house was constructed. It is situated on the grounds of Malacañang Golf Club. It was called Bahay Pangarap (Dream House).

When Marcos was overthrown in the 1986 People Power Revolution, the Palace complex was stormed by protesters who roamed the grounds. The international worldwide media subsequently exposed the excesses of the Marcos family that the latter had left at the Palace during the few hours it had before it fled to Hawaii, including Mrs. Marcos' infamous collection of thousands of shoes. The main Palace was later reopened to the public and was converted into a museum for three years.

After Marcos' exile, a lifestyle of excess was revealed. Some of these excesses include 15 square feet of a sunken bathtub with a mirrored ceiling and an altar with a 19th-century religious statuary of ivory with gold-embroidered robes.

In an effort to distance herself from the decadence of the Fourth Republic, President Corazon Aquino chose to live in the nearby Arlegui Mansion but held government affairs in the Executive Building. Her successor, President Fidel Ramos, followed suit. After the Second EDSA Revolution, security in the Palace was tightened due to attempts against the government. Ramos' First Lady restored Bahay Pangarap, which became an extension of the Malacañang Ceremonial Hall. The chapel was also retained, despite Ramos' different religious point of view (Ramos was a Protestant).

President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who had once resided in Malacañang during the rule of her father, President Diosdado Macapagal, chose to live again in the main Palace after her accession in 2001.

Two presidents (Former president Benigno Aquino III and President Rodrigo Duterte[13]) chose to reside in the Bahay Pangarap, the guest villa on the south bank of the Pasig River across the main Palace.

Buildings

Malacañan Palace

The Main Palace contains 10 current main existing halls, some restored from historical times.

Entrance Hall

Official visitors to Malacañan Palace use the Entrance Hall. Its floor and walls are of beige Philippine marble. Straight from the entrance hall are the doors to the Grand Staircase leading to the state reception rooms. To its left is the Palace chapel and the passage to the right leads to Heroes Hall.

The doors leading to the Grand Staircase depict the Philippine mythology of Malakas (Strong) and Maganda (Beautiful), the first Filipino man and woman who emerged from a large bamboo stalk. The present resin doors were installed in 1979, replacing wrought iron and painted glass doors from the American period depicting Lapu-Lapu and the other Mactan chieftains who felled Ferdinand Magellan.

A pair of lions used to stand guard on each side of the doors to the Grand Staircase. The lions were originally at the vestibule of the Ayuntamiento Building in Intramuros. They were apparently discarded during the 1978–79 renovations. Wooden benches dating back to the American Regime that were in the Hall were transferred to the private entrance that lead directly to the living quarters of the Palace.[14]

Heroes Hall

From the Entrance Hall, one walks through a mirrored passage hung with about 40 small paintings of famous Filipinos painted in 1940 by Florentino Macabuhay. The adjoining large room was originally the Social Hall, intended for informal gatherings. It was renamed Heroes Hall by First Lady Eva Macapagal, who commissioned Guillermo Tolentino to sculpt busts of national heroes.

In 1998, the National Centennial Commission installed three large paintings specially commissioned for the place. The one in the vestibule is by Carlos Valino, while the two others are by a group of artists headed by Karen Flores and Elmer Borlongan.

The painting in the vestibule is chronologically the second of the three, depicting events of the Propaganda Movement (Marcelo H. Del Pilar, José Rizal, etc.) and the Philippine Revolution from the formation of the Katipunan by Andrés Bonifacio, the sewing of the Philippine flag, the Proclamation of Independence at Kawit, and the Malolos Congress. At Heroes Hall itself are the other two paintings.

As one enters from the vestibule, the painting on the left shows key events from the earliest times (arrival of the ancient Filipinos and the Manunggul Jar) through Lapu Lapu and the death of Magellan, the Muslim resistance to Spanish rule, the Basi Revolt, and Gabriela Silang, to the 1872 martyrdom of the priests Gomez, Burgos and Zamora.

The painting on the right begins with the Battle of Tirad Pass and Gregorio Del Pilar and other events of the Philippine–American War, the Independence Movement under Osmeña and Quezon, events of the Japanese occupation, and the Presidents of the Philippines all the way to the Marcoses, President Corazon Aquino, and President Ramos.

The Hall, as large as the Ceremonial Hall directly above, received a mirrored ceiling in 1979 and for the rest of the Marcos era was used not only for meetings and informal gatherings but also for state dinners in honor of visiting heads of state. Dinner was usually followed by a cultural presentation, after which formal toasts were offered by the President and the guest of honor.[14]

Grand Staircase

Past the Malakas and Maganda doors of the Entrance Hall is the Grand Staircase, made of the finest Philippine hardwood and carpeted in red. Its walls are made of tiny pieces of wood, assembled to simulate sawali panels. These were put up in 1979 replacing the stucco and hardwood panels. At the top of the stairs is the landing that serves as vestibule to the Reception Hall.

The Spanish and American Governors General and Philippine Presidents and their visitors used this staircase. The staircase was narrower before the Marcos reconstruction. There is a story that José Rizal's mother, Teodora Alonzo, went up these stairs on her knees to beg the Governor General Camilo Polavieja for her son's life.

A legacy of the Spanish regime are unsigned portraits of Spanish conquistadores Hernando Cortés, Sebastian del Cano, Fernando Magallanes, and Cristobal Colon, hanging at the balcony around the stairs. At the end of the balcony a magnificent harvest scene by Fernando Amorsolo hangs.

A large painting of Nereids (sea nymphs) by noted Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla used to hang in place of the Luna. A case of Marcos war medals, subsequently alleged to be fake, took its place towards the end of the Marcos regime. The case continued to be on display, empty, for some years thereafter.

To the left as one reaches the top of the stairs, is the famous 'The Blood Compact', painted by Juan Luna in 1886, still in its original carved frame. It was given to the government in return for the artist's scholarship in Spain. The door on the left leads to the private quarters of the presidential families. This wing contained the private dining and living rooms and two guest suites, used for meetings and waiting rooms between 1986–2001, while Presidents Corazon Aquino and Fidel Ramos lived at the Arlegui Guest House and President Estrada lived at the Premier Guest House. President Arroyo and her family lived in this wing. The door straight ahead leads to a corridor that surrounds the inner court within the private quarters.[14]

Reception Hall

Visitors assemble in this impressive room prior to a program or state function at the Ceremonial Hall beyond, or while waiting to be received by the President or the First Lady at the Study Room or the Music Room to its left, or before entering the State Dining Room on the right.[15]

This room was the largest in the Palace before the 1979 renovation. Easily the most outstanding feature of the Reception Hall are the three large Czech chandeliers bought in 1937 by President Quezon. These have always been treasured and during the Second World War, were carefully disassembled prism by prism and hidden for safe-keeping. They were taken out and reassembled after the war.

Official portraits of all Philippine Presidents are on the walls, from Emilio Aguinaldo, President of the Malolos Republic, to Rodrigo Duterte, painted by Fernando Amorsolo, García Llamas and other noted artists. The first portrait of President Arroyo in this hall was a photograph taken by Rupert Jacinto. That of President Fidel Ramos is unique on three counts – it is on a narra plank rather than on canvas, the likeness as well as the decorations along the sides are painstakingly singed on the wood and it was a gift of the artist, Gaycer Masilang, a prisoner serving a life sentence.

An elaborate ceiling was installed in the 1930s, carved by noted sculptor Isabelo Tampingco who depicted vases of flowers against a lattice background. Large mirrors, gilt sofas and armchairs, and Chinese bronze pedestals holding plant and flower arrangements decorate the Hall. The Tampingco woodwork was curved and in some eyes gave the room a coffin shape. This is supposedly why in the 1979 renovation, the Tampingcos were replaced with two facing balconies.[14]

Rizal Ceremonial Hall

This room, the largest in the Palace today, is also known as the Ballroom, used for state dinners and large assemblies, notably the mass oath takings of public officials begun by President Ramos. The upholstered benches are lined up for guests on such occasions. When the room is used for state dinners, the benches are removed and round tables set in place. Orchestras sometimes play from the minstrels' galleries at two ends of the hall.[16]

Three large wood and glass chandeliers illuminate the Hall. Carved and installed in 1979 by the famous Juan Flores of Betis, Pampanga, the chandeliers are masterpieces of Philippine artistry in wood.

The Hall used to be much smaller and was in effect merely an extension of the Reception Hall. It had a coved ceiling similar to those of old Philippine homes, and glass doors opening to verandahs on three sides overlooking the Pasig and Malacañang Park. Many an al fresco party was held here, with round tables set on the azoteas and verandah for dinner and the Ceremonial Hall, doors thrown open, cleared for dancing. Fireworks lit the skies promptly at midnight from the Park across the river at New Year's Eve parties. The azoteas (covered patios), verandas and the intimate pavilion in the middle were combined in 1979 into the present enormous Ceremonial Hall.

A recurring Palace ritual is the presentation of credentials when a new Ambassador arrives. During the Marcos Administration and prior to the 1979 renovation, new Ambassadors presented their credentials in an impressive ceremony. A flourish of trumpets accompanied the arriving Ambassador as he mounted the Grand Staircase and marched the full length of the Reception Hall. The yellow-gold curtains to the old Ceremonial Hall were parted to reveal the President standing alone at the far end, with members of the Cabinet lined up on the left. The Ambassador presented his documents of credence to the President, who handed them to the Foreign Secretary. The President then delivered his welcome speech and offered a champagne toast to the head of state of Ambassador's home country. The Ambassador then delivered his response, offered a toast to the President, and after small talk, left in another burst of trumpets.

Presidents Corazon Aquino and Ramos were less formal, receiving new Ambassadors in the Music Room without ceremony. The old rituals were revived by President Estrada, when an arriving diplomat disembarked from his car at General Solano Street and boards what is called a chariot, a luxurious open jeep where the occupant stands on a red carpet holding onto a stout bar while progressing up J.P. Laurel Street to the Palace grounds. He received military honors in the garden outside the main entrance and to fanfare, is escorted up to the Reception Hall. He marched through two columns of guards in gala uniform to present his credentials to the waiting President.[14]

State Dining Room

The State Dining Room is used mainly for Cabinet meetings. Before the 1935–37 renovations, this room was the ballroom of the Palace. This is where Presidents dined with state guests and official visitors. A long adjustable table could accommodate up to about fifty guests. The President would sit at the center of the table and the First Lady across from him. The best glassware (Irish Waterford and French St. Gobain) and china (Limoges and Meissen) were brought out on special occasions. The chandeliers are Spanish, from the Ayuntamiento Building in Manila, as are the gilded mirrors that seem have been here since the Spanish Regime.

Two paintings dominate the room. The larger is a fiesta scene by National Artist Carlos Botong Francisco – a pair of tinikling dancers, a serenade, churchgoers, boatmen, and other vignettes of rural life. Commissioned for the Manila Hotel, it originally hung in one of the hotel lobbies but was transferred to Malacañan Palace in 1975. The other painting is an early Amorsolo rural scene.

The room was widened and a mirrored ceiling installed in 1979. Previously, there was a long dining table at center and the decorations consisted of heavy crimson velvet curtains, large gilded mirrors and elaborate chandeliers.

Beyond is a smaller room just as long but narrower than the dining room called the Viewing Room. The room was intended for Cabinet meetings and film showings. The room proved rather small and was rarely used as such, it was more frequently used to hold buffets for people meeting in the State Dining Room. Another 1979 renovation, this occupies what was a verandah overlooking the Palace driveway and garden.[14]

The State Dining Room is also where Emilio Aguinaldo was kept prisoner after his capture by the Americans in Palanán, Isabela in 1901. One of the most dramatic scenes in Palace history occurred here. In The Good Fight, President Quezon wrote that "in April 1901, I had walked down the slopes of Mariveles Mountain, a defeated soldier, emaciated from hunger and lingering illness, to place myself at the mercy of the American Army." Suffering from malaria, he was also instructed to verify that Aguinaldo had in fact been captured. In Quezon's words,

... I was ushered into the office of General Arthur MacArthur, the father of the hero of the Battle of the Philippines. ... [The interpreter]... told General MacArthur in English what I had said in Spanish, namely, that I was instructed by General Mascardo to find out if General Aguinaldo had been captured. The American General, who stood erect and towered over my head, raised his hand without saying a word and pointing to the room across the hall, made a motion for me to go in there. Trembling with emotion, I slowly walked through the hall toward the room hoping against hope that I would find no one inside. At the door two American soldiers in uniform, with gloves and bayonets, stood on guard. As I entered the room, I saw General Aguinaldo the man whom I had considered as the personification of my own beloved country, the man whom I had seen at the height of his glory surrounded by generals and soldiers, statesmen and politicians, the rich and the poor, respected and honored by all. I now saw that same man alone in a room, a prisoner of war! It is impossible for me to describe what I felt, but as I write these lines, forty-two years later, my heart throbs as fast as it did then. I felt that the whole world had crumbled; that all my hopes and dreams for my country were gone forever! It took me some time before I could collect myself, but finally, I was able to say in Tagalog, almost in a whisper, to my General: Good evening, Mr. President.

Presidential Study

The Presidential Study is the official Office of the President, equivalent to the United States' Oval Office of the White House. Formerly known as the Rizal Room, this is where Presidents from Quezon to Marcos and then Ramos received their daily stream of callers. It is currently on the second floor of the Palace itself, while the old Executive Office at Kalayaan Hall (the old Executive Building) has been renamed the Quezon Executive Office.

The presidential desk is the same in use since the Commonwealth of the Philippines. It was used by all presidents from Quezon to Marcos, who use it officially until 1978 when he used his private study. Marcos had an ornately carved top added to the desk in 1969. It was restored by President Ramos, used by President Joseph Estrada, and restored once more by President Arroyo. She made the Study into a conference room with the Council of State table of the Commonwealth as centerpiece, until she finally restored the room to its original function as the President's Office.[14] There is a large chandelier in the Study from the 1935–1937 renovations. Behind the Presidential Study is a small conference room called the Study Conference Room.

Music Room

The room's usage changed over the years. It was a bedroom during the American period; turned into a library and reception room during the Commonwealth; after the war, it eventually became the Music Room. First Ladies customarily received callers in this room. A Luna masterpiece, 'Una Bulaqueña' hangs above the grand piano. 'A Cellist,' painted by Miguel Zaragoza, hangs as its pendant across the room above the sofa. The wall niches now hold Chinese trees and flowers made of semi precious stones, where there used to be Guillermo Tolentino sculptures representing the different fine arts and later, large Ming and Qing porcelain vases. A supposed Michelangelo, a stone head, was once here.

Imelda Marcos decorated the room in mint green. She would sit on the antique French sofa and the visitors on the armchairs. On rare occasions, small concerts were held here, featuring famous Filipino and foreign musicians.

The room immediately behind the Music Room was set up by Imelda Marcos as her office. It later became President Fidel Ramos' private office. The room beyond was originally a small sitting room and was converted by President Joseph Estrada into his own office. President Arroyo decided to use the room as her office at first. Today, the room is used by the President to receive visitors.[14]

Private quarters

Each new presidential couple took their pick of the available bedrooms, each President frequently avoiding the bedroom of his predecessor.

A President with many children or grandchildren usually had problems, particularly when a foreign head of state arrived, expecting to be invited to stay in the Palace such as when Indonesian President Sukarno visited President Quirino shortly after the war, like many personalities who have stayed beforehand in Malacañang over the years. It is recounted that the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, dropped by in the 1920s to play polo. American and Asian heads of state have stayed at Malacañan Palace on visits to Manila.

With three grown children, leaky roofs, noisy air conditioners, and cramped space, the Marcos family decided to expand the Palace in 1978. The bedrooms of President and the First Lady were enlarged and suites were built for their children Ferdinand, Jr., Imee, Irene, and their niece Aimee. The private living room was expanded and the entire private quarters generally added to or enlarged resulting in the present-day structure.

Bedroom Suites. The bedroom suites open from the former private dining room, between which is a small sky-lit room that used to be a courtyard. These are furnished with large canopy beds, gilded wardrobes and the like. The King's Room leads to the balcony over the main entrance, from which Pope John Paul II blessed a waiting crowd during his 1981 Philippine visit and which President Arroyo confides was her bedroom as the young daughter of President Diosdado Macapagal.

The rooms are large, furnished expensively, and impressive, but are not quite the stupendous rooms that 'in comparison make Versailles Palace look like a hovel,' as a foreign observer declared.

The Spanish period "Malacañan Palace" probably centered on the small, open-roofed inner court that leads to all areas of the private quarters. The rooms opening to the Grand Staircase were the Dining and Living Rooms and guest suites of the Marcos period. These became meeting rooms during the Ramos and Estrada administrations and reverted to being the private quarters of the presidential family under President Arroyo.

Reception Room. This was the family dining room of Presidential families until the 1979 renovation. It used to have a magnificent coffer ceiling in the Filipino-Spanish style. The famous painting of Fabián de la Rosa, Planting Rice, used to hang on one wall. Other paintings, notably those by Fernando Amorsolo, were here and in the adjoining room.

The room beyond was used by the Marcos family variously as private living room and a chapel. It became Meeting Room No. 1 in the Aquino, Ramos, and Estrada presidencies. A large Botong Francisco painting of dancers is on one wall. Brought from the Manila Hotel, this artwork is a pair to the one in the State Dining Room.

Discothèque. The third floor added in 1979 has a roof garden and a discothèque. Reached by an elevator, the disco is immediately above President Marcos' bedroom. It was complete with strobe and infinity lights, fog equipment, and the latest in music equipment then. A wide waterfall-fountain plays on the terrace outside the disco and steps lead up to a rooftop helipad. It has apparently been disused since 1986.[14] During the Macapagal-Arroyo administration, it was renovated into a Music Hall.[17]

Paranormal activity

Alleged paranormal activity has been reported as occurring in the Palace, including one that some identified to be the long deceased valet of President Quezon, who occasionally ministered to favored guests.[18]

Kalayaan Hall

The Old Executive Building now Kalayaan Hall, now the oldest part of the Palace, was constructed in 1920 Governor General Francis Burton Harrison. Till then, the Governors General had to commute daily to their office at the Ayuntamiento Building in Intramuros. Gov. Gen. Leonard Wood was the last chief executive to hold office there and the first in Malacañan Palace.[4] It was their first concrete structure in the palace grounds and was enlarged over the years until 1939. It combines the histories of the American, Commonwealth, and Second and Third Republics, on the grounds of the picadero pavilion of the Spanish period.[19]

The Renaissance-revivalist architecture of Kalayaan Hall, elegant with its high-arched windows, once glittered with Romblon marble embedded into the concrete of its façade, but subsequent coats of white paint since the 1960s have obscured this. Kalayaan Hall has remained intact after the war and withstood the test of time, serving as link between the old and the new. The precast ornamentation, elaborate wrought iron porte-cochère and balconies, the loggias and high ceilings ideal for the circulation of air under tropical conditions, all created a building of imposing appearance. For generations, the executive functions of the Philippine state were conducted in this building. The Building held the Office of the Press Secretary and other offices on the ground floor until early in the Arroyo administration.[19]

The main hall at the second floor of Kalayaan Hall was once the location of the guest bedrooms during the American era, and then of offices for the Office of the President during the Commonwealth. This is where former United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower worked as a Major in the U.S. Armed Forces and military adviser to the Commonwealth government. In 1968, it was cleared and renovated to form a large room called Maharlika Hall. It became the site for state dinners and citizens’ assemblies during the Marcos administration. Until 1972, the second floor was a warren of offices, including those of the Executive Secretary and the Vice President. An elegantly paneled office on the second floor used to be the President's Executive Office until President Ferdinand Marcos began to use the Study Room (now the Presidential Study) of the Palace itself. It was from the front west balcony of this hall where he took his last public oath of office and delivered his farewell speech on February 25, 1986. It was subsequently used as the Office of the Press Secretary until 2002, when it was transformed into the main gallery of the Presidential Museum and Library.[19]

Presidential Museum and Library

The Presidential Museum and Library, formerly Malacañang Museum, the official repository of memorabilia of the President of the Philippines, is located in Kalayaan Hall. It was established in 2004 when the Presidential Museum and Malacañang Library were merged into the Malacañang Museum then renamed to its present name in 2010. The Gallery of Presidents features exhibits and galleries showcasing the heritage of the Presidents beginning from Emilio Aguinaldo to the present. It is composed of objects and memorabilia – including clothing, personal effects, gifts, publications and documents of former presidents as well as the artwork and furniture from the Palace collections.[20]

Former Presidential Museum

Prior to 2004, the Presidential Museum was a distinct entity from the Malacañang Library. The Quezon, Osmeña, Roxas, Quirino, Magsaysay, and García Rooms of the Presidential Museum under the Ramos and Estrada administrations occupied the suites formerly allotted to the Marcos children (Ferdinand, Jr., Imee and Irene) which open from the inner court corridor. Most of these rooms were added in 1978 when the José P. Laurel St. front of the Palace was moved forward.

Magsaysay Room

The first in the series was the Magsaysay Room, furnished as the entrance lobby to the private quarters.

García Room

The García Room was a game room, containing chess sets that President García owned and which were lent by his family. These and the other President's rooms included portraits, furniture and memorabilia on loan from the President's families.

Bedroom of Imee Marcos

The former bedroom of Imee Marcos had an antique gilded arch made by Isabelo Tampingco, carved to represent a coconut tree complete with fruit and leaves. Shelves held her collection of 19th century French porcelain dolls. At one time, now-Senator Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. lived elsewhere and used his room to practise golf. Nets were hung on all walls to catch flying balls.

Laurel Room

The Marcoses made this room into a library with bookcases on all sides. It was used to exhibit memorabilia of President José P. Laurel.

Aguinaldo Room

Furnished as a dining room with the Malolos Congress table borrowed from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas and an original flag used during the Philippine Revolution (captured by an American soldier and returned by his descendants decades after), this room was at one time the Marcos Family Chapel. Antique and modem religious images were arranged around the room, including figures of the Santo Niño, the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint Lorenzo Ruiz. There was an exquisite silver altar frontal, probably dating from the 18th century. President Marcos had numerous devotions, including one to Saint Martín de Porres.

Ramos Room

The dressing room of Mrs. Marcos adjoined her bedroom and has windows opening to the garden and J.P. Laurel Street. Together with the large walk-in vault for valuables, it is now used to display Ramos memorabilia.

Marcos Room

The room contains Marcos memorabilia, including a whiteboard on which is drawn a map of Camp Crame, evidently used in February 1986 to devise or present a plan to attack the Enrile-Ramos forces. This was the bedroom-sitting room of Mrs. Marcos. Almost as large as that of President Marcos', it had a large bed with pina cloth bedspread and cushions. From the canopy was hung a mosquito net, arranged in Spanish Regime style. A railing surrounded the bed, reminiscent of the state bedrooms at European palaces. There was an Austrian Bosendorfer grand piano, regarded as among the best concert pianos in the world. A similar piano was at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

The bathroom (not open to visitors) is accented in green malachite, the bathtub surrounded by a mural of Olot Beach in Mrs. Marcos' native Leyte province. Concealed doors lead to a walk-in safe that once contained Mrs. Marcos' fabled jewels and to a staircase leading to the ground floor room that contained Mrs. Marcos' clothes and accessories, including ternos and the much publicized 3000 shoes (actually 1500 pairs). The Quezon bedroom was on this site.

Macapagal and Estrada room

The memorabilia of President Macapagal and exhibits on President Estrada were exhibited in this large room, formerly the bedroom of President Marcos. With windows to the Palace garden and the Pasig River, the room used to have a large bed with an elaborate headboard and a round canopy that held a mosquito net. The Palace, ironically, needed mosquito nets – it must have been tough to catch even one in such large and high rooms. A desk, video equipment and medical paraphernalia completed the room's furnishings. President Marcos apparently liked to have his grandchildren sleep with him in this room, on mattresses laid out on the floor.

The en-suite bathroom (closed to visitors) is large, its bathtub surrounded by a mural of Paoay Lake which is near President Marcos' native Batac, Ilocos Norte. The view is the same as that seen from the Presidential retreat of Malacañang ti Amianan (Malacañang of the North).

Corazon Aquino Room

This was the Marcos Family Dining Room, with a kitchen alcove behind a sliding screen. Mrs. Marcos liked to cook and frequently did so in this kitchen for family members and close friends. With numerous family recipes, she liked to improvise.

New Executive Building

On the other side of the Palace grounds, beyond the President's Residence is the New Executive Building. This was the administration building of San Miguel Corporation until bought by government. President Manuel L. Quezon first proposed the purchase of the nearby San Miguel Brewery as additional office space in 1936. President Ferdinand E. Marcos initiated plans to transform it into an integral part of the Palace, the former San Miguel Brewery buildings were demolished upon the expansion in 1978–79, paving way to a park near the San Miguel Church. However, it was in 1989 under President Corazon C. Aquino that its reconstruction and refurbishing as the New Executive Building took place.[21]

Its architectural elements deliberately pay homage to the Palace of the Third Republic of the Philippines. Its utilitarian nature, however, made possible much needed additional administrative space, although its newness and lack of proximity to the Palace led to the resumption of the use of the Palace itself by Aquino’s successors, Presidents Ramos and Estrada. Currently, it houses the Office of the Presidential Spokesperson, Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office, Presidential Communications Operations Office, and the Malacañang Press Briefing Room. Across the street is a Spanish colonial period house adapted to office use now known as the Bahay Ugnayan (Ugnayan House).[21]

Mabini Hall

The current Administration Building or Mabini Hall on Ycaza Street is the large structure to the left upon entering Gate 4. It began as the Budget Building upon the creation of the Budget Commission (now the Department of Budget and Management) in 1936. After World War II, it temporarily housed the Supreme Court, as the Ayuntamiento building wasdestroyed during the Battle for Manila in February 1945. After the war, it was later expanded with wings and top floors added. It houses the Office of the Executive Secretary, some units of the Department of Budget and Management, and offices of Presidential assistants and advisers. Some offices in this building, particularly those of the Office of Media Affairs, were invaded by an unruly mob on the evening of February 25, 1986, during the storming of Malacañang that capped the People Power Revolution. After it was gutted in a fire in 1992, plans to demolish it and build a high-rise building in its place were completely dropped due to budgetary constraints. President Fidel V. Ramos supervised its reconstruction into a spartan but well-ventilated and lit office complex, and renamed it Mabini Hall, after Apolinario Mabini.[22]

Bonifacio Hall

The Premier Guest House (now Bonifacio Hall), the glass-fronted building across the garden from the Palace's main entrance, was originally built by the American Governors General as servants' quarters to screen off Malacañang from the brewery (San Miguel) next door. The building was remodeled into the Premier Guest House in 1975 for use during the IMF-World Bank Boards of Governors Meeting.

The building, separate from the palace itself, became the temporary residence of the Marcos family while the main Palace was being reconstructed in 1978–1979, when repairs were made to the Palace after a fire in 1982, and when the air purification system was being improved in 1983. President Corazon C. Aquino used this building as her office from 1986 to 1992. The Ramos administration relegated this building to secondary status despite its integration into the New Executive Building. It was renovated in 1998 as a residence and office for President Joseph Estrada and his family. His and Mrs. Estrada's bedroom was on the second floor, where Pres. Marcos' bedroom and President Corazon Aquino's office were. Pres. Estrada's office was on the ground floor.

The front of the building facing the garden is a two-story high reception area, with a staircase in the center that leads to the corridor above. The President's office was on the ground floor, near the stairs. On the floor above were bedrooms and the family dining room.

In 2003, President Gloria Macapagal–Arroyo renamed this building Bonifacio Hall in honor of Andrés Bonifacio. The private office of then-President Benigno S. Aquino III is located at the Aquino Room in Bonifacio Hall. After the building's structural integrity was called into question, Aquino's office was temporarily moved to the Presidential Study on June 21, 2011.[23]

Malacañang Park and Bahay Pangarap

Malacañang Park, directly across the river from Malacañan Palace, adjoins the Mabini Shrine and the former quarters of the Presidential Security Command and of the National Intelligence and Security Agency. It boasts a Recreation Hall, a small golf course and the guesthouse Bahay Pangarap.

The park was created when the rice fields and grasslands of Pandacan on the south bank of the Pasig River were acquired on orders of President Manuel L. Quezon in 1936–1937. Intended as a recreational retreat, it contained three buildings: a recreation hall used for official entertaining, a community assembly hall for conferences with local government officials, and a rest house directly opposite the Palace across the Pasig River, which would serve as the venue for informal activities and social functions of the President and First Family. The buildings, constructed by the Bureau of Public Works, were designed by Juan M. Arellano and Antonio Toledo. In addition to the buildings are a putting green, stables, and shell tennis courts.[24]

President José P. Laurel had the putting green expanded into a small golf course after an assassination attempt at the Wack-Wack golf course. The existing gazebo at the golf course dates to the Laurel administration. President Manuel Roxas further improved the golf course as well as maintaining a truck garden as part of the food self-sufficiency program of his administration.

During the administration of President Ramon Magsaysay, a marshy area was filled-in joining the properties of Malacañang Park and the Bureau of Animal Industry building as part of a GSIS housing project for presidential guards and other workers. The Park grounds were refurbished through the efforts of First Lady Eva Macapagal in the early 1960s. She renamed the rest house Bahay Pangarap (House of Dreams).

In the subsequent presidency of Ferdinand E. Marcos, Malacañang Park became increasingly identified with the Presidential Guards. It was during the Marcos administration that the Bureau of Animal Industry building became the headquarters of the Guards (known today as Presidential Security Group or PSG). General Fabián Ver gained jurisdiction over some of the historic buildings, including the recreation hall, which became (and remains) the PSG gymnasium, and the community assembly hall which was turned into the presidential escorts building. Malacañang Park, though, has always been a recreational park and not a military facility. The facilities and area of the PSG are distinct from the demarcation of Malacañang Park.

Under President Fidel V. Ramos, the Bahay Pangarap was restored and became the clubhouse of the Malacañang Golf Club (the old Clubhouse became the former residence of Marcos’s mother, Mrs. Josefa Edralin Marcos). Restoration was supervised by Francisco Mañosa at the initiative of First Lady Amelita Ramos and inaugurated as the New Bahay Pangarap on March 15, 1996 as an alternate venue for official functions in addition to recreational and social activities.

In 2008, the historic Bahay Pangarap was essentially demolished by Conrad Onglao and rebuilt in contemporary style (retaining the basic shape of the roof as a nod to the previous historic structure), replacing, as well, the Commonwealth-era swimming pool and pergolas with a modern swimming pool. It was inaugurated on December 19, 2008 by President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo at a Christmas reception for the Cabinet. Administrative Order Nº. 251, issued on December 2008, placed the administration of Bahay Pangarap under the Internal House Affairs Office of the Office of the President of the Philippines.

Former president Benigno S. Aquino III became the first President of the Philippines to make Bahay Pangarap his official residence, although previous presidents have stayed there.[25] Despite living at his private residence at the start of his term, he has since occupied the house from August 2010 until July 2016. His successor, incumbent president Rodrigo Duterte is the second president to reside at the said house.

Other buildings

Satellite facilities outside the Palace proper but within the gated Palace complex include a television station, two churches and various other guesthouses in addition to the Premier Guest House.

- Laperal Mansion or the Arlegui Guest House is a remodeled and enlarged 1930s mansion located along Arlegui Street, half a block away. When World War II broke out, it served at one point as the residence of the speaker of the National Assembly established by the Japanese puppet state, Second Philippine Republic, Benigno S. Aquino, Sr., the grandfather of former Philippine president Benigno S. Aquino III. When the war ended, it served temporarily as the National Library. Around the early postwar era that the Laperal family acquired the property. In 1975, the property was seized by the presidential security forces under Marcos for “security reasons". The house became the office of the Presidential Economic Staff (precursor of today’s National Economic and Development Authority) before former First Lady Imelda Marcos decided to expand the house to grander proportions to become a guesthouse, giving the building two turrets when it used to have one.

- After the 1986 People Power Revolution, Corazon Aquino as a symbolic counterpoint to the opulence of the Marcos regime refused to live in the Palace as her predecessors have, choosing instead to stay at the Arlegui Guest House. Her successor, Fidel V. Ramos, followed suit and also resided in Arlegui. During Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s term, the house became the Office of the Press Secretary.

- Legarda Mansion was built in 1937 by Doña Filomena Roces y de Legarda, one of the first art deco houses built in Manila. In this house, Alejandro Legarda, the son of Doña Filomena, lived with his wife Ramona Hernández, and their four children. Doña Ramona was well known for her lavish parties. The Legarda house is a tribute to Doña Ramona (Moning), as it houses La Cocina de Tita Moning, a fine dining restaurant that aims to recreate the wonderful parties of Manila’s most elegant era, using heirloom recipes of the Legardas, served on antique china, glassware, and silverware. The house includes living room with paintings by Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo and Juan Luna, Don Alejandro’s collection of antique radio equipment, a dressing room showcasing the memorabilia of the Legarda women, and the dining room where banquets are held.

- Goldenberg Mansion, on General Solano Street, is a historic structure built in the 19th century by the Eugster family and passed into the possession of the Oidor de la Audiencia (Judge of the Court), José Moreno Lacalle. It also served as home of the Spanish Navy Admiral and the Spanish Royal Navy Club from 1897–98. When the Americans arrived, the house served as the home and headquarters of the US Military Governor Arthur MacArthur, father of Gen. Douglas MacArthur. This also served as the session floor of the Philippine Senate for its historic first session in 1916.

- It was later bought by cosmetics manufacturer Michael Goldenberg (hence its name) and was eventually bought by the Philippine government during the Marcos regime in 1966, which became the office of the Marcos Foundation, a cultural heritage structure. National Artist Leandro Locsin did the restoration of the house which is filled with artifacts like antique furniture, pottery, and books from here and other parts of the world. It held Mrs. Marcos' collection of excavated porcelain and pottery, Ban Chieng prehistoric pottery from Thailand and Filipiniana book rarities, and treasures such as a statue from Angkor and Chinese jade furniture. It is still used occasionally for official functions.

- Teus House, on General Solano Street, was bought by the Marcos government and was converted into a guesthouse in 1974 under the supervision of Manila interior designer Ronnie Laing. It has a large living-dining area that used to hold a display of antique European silverware (that have since been sold at auction), including some by famous 18th and 19th century silversmiths Paul de Lamerie and Paul Storr. Much of these were apparently gifts to the Marcoses on their silver wedding anniversary in 1979. Some of these gifts are allegedly could still be found in the house. Access to the house is restricted.

- Two other Spanish colonial houses on Gen. Solano Street were bought by the Marcoses in the 1970s and remodeled also into guesthouses and office of the Marcos Foundation.

- Valdés Mansion along San Rafael St. in San Miguel, near the Plaza Avilés/Freedom Park. Unlike the aforementioned mansions, the house has not been maintained. Nevertheless, it currently serves as one of the offices of the Palace security.

- Presidential Broadcast Staff Radio Television Malacañang (PBS-RTVM) was organized in 1986 following the peaceful EDSA revolt. Before 1986, the organisation that existed was Radio-Television-Movies, and adjunct of the National Media Production Centre which was based in Malacañang. In 1987, Executive Order Nº. 297 dated 25 July 1987 was signed and issued by President Corazon C. Aquino, creating the Office of the Press Secretary and cites under Section 14 (Attached agencies) the creation of the Presidential Broadcast Staff (Radio-Television Malacañang).

- Executive Order No. 297 designated the PBS-RTVM as the entity with the sole responsibility and exclusive prerogative to decide on policy / operational matters concerning the television medium as it is utilised for the official documentation of all the President's activities for news dissemination purposes and video archiving.

- PBS-RTVM is involved in television coverage and documentation, and news and public affairs syndication of all the activities of the President, either live or delayed telecast, by national or local, government or private collaborating networks

- San Miguel Church was established by the Jesuits in 1603 adjacent to the Tripa de Gallina (river bend) and became a parish church in 1611. The church also ministered to Japanese Christians fleeing persecution under the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1615, and since many of these exiles belonged to the samurai, or the warrior class, the church was dedicated to Saint Michael. It was moved to its present location in 1783 under the Parish of Quiapo. The present church, erected in 1918, is notable for the symmetry of its twin bell towers, following the model of European Baroque architecture. The church was declared as the National Shrine of Saint Michael, the Archangel in 1986.[26]

Gardens

The extensive grounds of Malacañang comprise one of the few parks in Manila, with tropical shrubbery, century-old acacia trees, and even a balete tree or two. The acacias are festooned with the cactus like 'Queen of the Night.' The broad lawns, lush trees and greenery indicate how Manila may have been when it was less populous and times were more leisurely.

The public garden now known as 'Freedom Park' fronts the Administration and Executive Buildings. It has statues symbolizing the four freedoms (religion, expression, want and fear), that were brought to Malacañang from the Manila International Fair of the 1950s. The statues were long forgotten at the cogon field that was then Rizal Park, when First Lady Eva Macapagal retrieved them. An Art Deco fountain from the 1930s still flows near the main Palace entrance. Cannons and lamp posts dating from the Spanish Regime accent odd corners.

A bamboo teahouse, built in 1948 as a rest house, no longer exists, but it used to be by the river near where the swimming pool is now located.

At the main entrance is the large balete tree with a reputed resident kapre. Usually lit with capiz shell globe lights, it is hung with multicolored star lanterns during Christmas. One time only, it was lit with thousands of flickering fireflies, captured from some distant towns where fireflies still abounded and released as a grand ephemeral gesture of a present for the then First Lady.

Marker from the National Historical Commission of the Philippines

The marker of Malacanan Palace was installed in 1941 at Malacañan Palace site, San Miguel, Manila. It was installed by Philippines Historical Committee (now National Historical Commission of the Philippines).[27]

| Malacanan Palace |

|---|

| THIS WAS THE FORMER SITE OF SUMMER RESIDENCE PURCHASED IN 1802 FROM LUIS ROCHA BY COLONEL MIGUEL JOSE FORMENTO, WHOSE TESTAMENTARY-EXECUTORS SOLD IT TO THE SPANISH GOVERNMENT IN 1825. BY ROYAL DECREES OF 1847, THIS PROPERTY WAS SET ASIDE AS THE SUMMER RESIDENCE OF THE GOVERNOR GENERAL. THE PALACE IN INTRAMUROS HAVING BEEN DESTROYED BY THE EARTHQUAKE OF JUNE 3, 1863, THE GOVERNOR GENERAL MOVED TO THIS PLACE, THEN KNOWN AS THE POSESION DE MALACAÑAN. THIS BUILDING WAS RECONSTRUCTED, NEW LOTS WERE PURCHASED, OLD GROUNDS RAISED, REGRADED AND PARKED DURING AMERICAN AND FILIPINO ADMINISTRATORS. EXTENSIVE IMPROVEMENTS WERE MADE IN 1929–1932 UNDER GOVERNOR GENERAL DWIGHT F. DAVIS AND IN 1935–1940 UNDER PRESIDENT MANUEL L. QUEZON, THE FIRST FILIPINO CHIEF EXECUTIVE TO OCCUPY THIS PALACE.

THE EXECUTIVE BUILDING ADJOINING WAS COMPLETED IN 1939.[27] |

See also

- Presidential Palace

- The Mansion, Baguio, the official summer residence of the President of the Philippines

- Malacañang sa Sugbo, the official residence of the President of the Philippines in the Visayas

- Malacañang of the South, the official residence of the President of the Philippines in Mindanao

- Quezon City Reception House, the official residence of the Vice President of the Philippines

- World's largest palace

References

- ↑ "Malacañan Palace Sesquicentennial". Presidential Museum & Library.

- ↑ Ramos, Marlon (August 26, 2016). "Duterte wants to rename Malacañang". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Residents of Malacañan Palace and their respective periods of residence". Presidential Museum & Library (Philippines). Retrieved on 2013-06-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Malacañan Palace". Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved on 2013-06-15.

- ↑ http://malacanang.gov.ph/about/malacanang/where-did-the-name-malacanan-come-from/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Official Gazette of the Philippines – www.gov.ph – Briefer on the new Malacañang Briefing Room signage

- ↑ De Moya y Jimenez, Francisco Javier (1882). "Las Islas Filipinas en 1882: estudios historicos, geográficos, estadísticos", pg. 274. El Correo, Madrid.

- 1 2 De Carlos, Abelardo (1896). "La Ilustracion española y americana, Part 2", pg. 171. Madrid.

- ↑ Montero y Vidal, D. Jose (1895). "Historia General de Filipinas, Tomo III", pg. 504. Impreso de Camara de S. M., Madrid.

- ↑ Sociedad Geografica de Madrid (1886). "Boletin de la Sociedad Geografica de Madrid, Tomo XXI", pg. 274. Imprenta de Fortanet, Madrid.

- ↑ "Government and Administration". Discovering Philippines. Retrieved on 2013-06-15.

- 1 2 Ocampo, Ambeth (1995). "Inside Malacañang". Bonifacio's Bolo. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing Inc. p. 122. ISBN 971-27-0418-1.

- ↑ Macas, Trisha (July 6, 2016). "Duterte picks Bahay Pangarap as official residence". GMA News. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Museum". Office of the President of the Philippines. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ↑ "Reception Hall". Presidential Museum & Library (Philippines).

- ↑ "Rizal Ceremonial Hall". Presidential Museum & Library.

- ↑ Robles, Raïssa (January 31, 2010). "Asking President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo about sex was easier than asking about politics and her feelings". raissarobles.com. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ↑ (2012-10-12). "Malacañan Palace Prowlers: Ghosts, elementals, and other phantasmagoric tales". Presidential Museum & Library. Retrieved on 2013-06-16.

- 1 2 3 "Kalayaan Hall". Presidential Museum & Library (Philippines). Retrieved on 2013-06-15.

- ↑ "About". Presidential Museum & Library (Philippines).

- 1 2 "New Executive Building". Presidential Museum & Library (Philippines).

- ↑ "Mabini Hall". Presidential Museum & Library.

- ↑ Conde, Chichi (2011-07-05). InterAksyon.com: "Aquino moves to Palace study as Bonifacio Hall office undergoes repair" InterAksyon.com.

- ↑ Enriquez, Marge C. (6 June 2010). "New President can live in style but homey House of Dreams". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ Esguerra, Christian V. (30 July 2010). "RP's most tightly guarded bachelor's pad is ready". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- ↑ "File:SanMiguelChurchjf2252 06.JPG". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved on 2013-06-15.

- 1 2 Historical Markers: Metropolitan Manila. National Historical Institute. 1993.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malacañang Palace. |

- Presidential Museum & Library – About Malacañan Palace

- (Archived) Office of the President – Malacañang Museum

- Inside Malacañan Palace

- Pictures of old Malacañan Palace

- Malacañang History & Maps at Discovering Philippines – Government and Administration

.jpg)