Maka hannya haramitsu

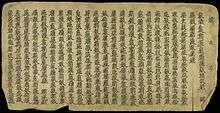

Maka hannya haramitsu (Japanese: 摩訶般若波羅蜜), the Japanese transliteration of Mahāprajñāpāramitā meaning The Perfection of Great Wisdom, is the second book of the Shōbōgenzō by the 13th century Sōtō Zen monk Eihei Dōgen. It is the second book in not only the original 60 and 75 fascicle versions of the text, but also the later 95 fascicle compilations. It was written in the summer of 1233, the first year that Dōgen began occupying his first monastery Kannondōri (later renamed Kōshō-ji) outside of modern-day Kyoto.[1] As the title suggests, this chapter lays out Dōgen's interpretation of the Mahaprajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Sūtra, or Heart Sutra, so called because it is supposed to represent the heart of the 600 volumes of the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra. The Heart Sutra focuses on the Buddhist concept of prajñā, or wisdom, which indicates not conventional wisdom, but rather wisdom regarding the emptiness of all phenomena. As Dōgen argues in this chapter, prajñā is identical to the practice of zazen, not a way of thinking.[2]

Allusions to other works

Although Dōgen's writing usually references other Buddhist works with heavy frequency, Maka hannya haramitsu only references the Heart Sutra, the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra, and a poem about a wind bell by his teacher, Tiantong Rujing. The poem is from Record of the Words of Master Rujing and is as follows:

The whole body is like a mouth hanging in empty space.

Not questioning the winds from east, west, south, or north,

Equally all of them, speaking of prajñā:

Ding-dong-a-ling ding-dong.[1]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Vowwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

According to Shohaku Okumura, the wind bell or hanging mouth represents ourselves while the winds represent all of the different circumstances that can face us. Regardless of what comes our way, we need not discriminate. When we view the world without discrimination, we express prajñā and see the reality of life. The last line is an onomatopoeia for the sound the bell makes, representing the expression of prajñā, wisdom of reality itself, as well as the interdependence of all things.[2]

References

- ↑ Nishijima, Gudo; Cross, Chodo (1994), Master Dogen's Shōbōgenzō, 1, Dogen Sangha, pp. 31–40, ISBN 1-4196-3820-3

- 1 2 Okumura, Shohaku (2012), Living By Vow: A Practical Introduction to Eight Essential Zen Chants and Texts, Simon and Schuster, pp. 134–135, 177, ISBN 9781614290100