Maithili language

| Maithili | |

|---|---|

| मैथिली | |

| Native to | India and Nepal |

| Region | Northern Bihar in India; Terai in Nepal |

| Ethnicity | Maithil |

Native speakers |

12 million in India (2001)[1] 3.1 million in Nepal (2011)[2] |

| Dialects |

|

|

Tirhuta (Mithilakshar) Kaithi (Maithili style) Devanagari | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

mai |

| ISO 639-3 |

mai |

| Glottolog |

mait1250[3] |

Maithili (/ˈmaɪtᵻli/;[4] Maithilī) is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in eastern Terai of Nepal and northern and eastern Bihar in India. It is written in the Devanagari script and is the second largest language of Nepal. In the past, Maithili was written primarily in Mithilakshar.[5] Less commonly, it was written with a Maithili variant of Kaithi, a script used to transcribe other neighboring languages such as Bhojpuri, Magahi, and Awadhi.

In 2002, Maithili was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, which allows it to be used in education, government, and other official contexts.[6] It is recognized as one of the largest languages in India and is the second most widely used language in Nepal.[7]

In 2007, Maithili was included in the Interim Constitution of Nepal 2063, Part 1, Section 5 as a Nepalese language.[8]

Geographic distribution

In India, Maithili is spoken mainly in northern Bihar in the districts of Madhubani, Darbhanga, Samastipur, Muzaffarpur, Sitamarhi, Begusarai, Purnia, Katihar, Kishanganj, sheohar, Bhagalpur, Madhepura, Araria, Supaul and Saharsa. Madhubani and Darbhanga constitute cultural and linguistic centers. Native speakers also reside in Delhi, Calcutta, Ranchi and Mumbai.[9]

In Nepal, Maithili is spoken mainly in the Outer Terai districts including Sarlahi, Mahottari, Dhanusa, Sunsari, Siraha and Saptari Districts. Janakpur is an important linguistic centre of Maithili.[9] It is spoken by various castes and ethnic groups such as the Brahmin, Chamar, Khatawe, Kurmi, Rajput, Yadav and Teli;[5]:265 and also by Bahun, Chhetri, Poddar, Pandey and Maithil Brahmin. A constitutional provision foresees the introduction of Maithili as medium of education at the primary school level.[7]

Classification

In the 19th century, linguistic scholars considered Maithili as a dialect of Bengali or Eastern Hindi languages and grouped it with other languages spoken in Bihar. Hoernlé compared it with Gaudian languages and recognised that it shows more similarities with Nepali languages than with Hindi. Grierson recognized it as a distinct language and published the first grammar in 1881.[10][11]

Chatterji grouped Maithili with Magadhi Prakrit.[12]

Dialects

Maithili varies greatly in dialects.[13] Several geographic variations of Maithili dialects are spoken in India and Nepal, including Dehati, and Kisan. Some dialects such as Bantar, Barmeli, Musar and Tati are spoken only in Nepal, while the Kortha, Jolaha and Thetiya dialects are spoken in India. All the dialects are intelligible to native Maithili speakers.[9]

Other dialects include:

- Thēthi is spoken between the western part of the Mahottari and the eastern part of the Sarlahi districts of Nepal, and in adjacent areas in Bihar.[14]

- The Madhubani dialect spoken in north India is generally considered to be the standard form.[15]:186

- Central Maithili is also considered as the standard form.[16]

- The Kulhaiya dialect is spoken in most of north-eastern Bihar.

The standard form of Maithili is spoken in Darbhanga and and Madhubani districts.[17]

History

Maithili dates back to the 14th century. The Varna Ratnākara is the earliest known prose text, preserved from 1507, and is written in Mithilaksar script.[10]

The name Maithili is derived from the word Mithila, an ancient kingdom of which King Janaka was the ruler (see Ramayana). Maithili is also one of the names of Sita, the wife of King Rama and daughter of King Janaka. Scholars in Mithila used Sanskrit for their literary work and Maithili was the language of the common folk (Abahatta).

With the fall of Pala rule, disappearance of Buddhism, establishment of Karnāta kings and patronage of Maithili under Harasimhadeva (1226–1324) of Karnāta dynasty, Jyotirisvara Thakur (1280–1340) wrote a unique work Varnaratnākara in pure Maithili prose, the earliest specimen of prose available in any modern Indo-Aryan language.

In 1324, Ghyasuddin Tughluq, the emperor of Delhi invaded Mithila, defeated Harasimhadeva, entrusted Mithila to his family priest Kameshvar Jha, a Maithil Brahmin of the Oinvar family. But the disturbed era did not produce any literature in Maithili until Vidyapati Thakur (1360 to 1450), who was an epoch-making poet under the patronage of king Shiva Simha and his queen Lakhima Devi. He produced over 1,000 immortal songs in Maithili on the theme of erotic sports of Radha and Krishna and the domestic life of Shiva and Parvati as well as on the subject of suffering of migrant labourers of Morang and their families; besides, he wrote a number of treaties in Sanskrit. His love-songs spread far and wide in no time and enchanted saints, poets and youth. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu saw divine light of love behind these songs, and soon these songs became themes of Vaisnava sect of Bengal. Rabindranath Tagore, out of curiosity, imitated these songs under the pseudonym Bhanusimha. Vidyapati influenced the religious literature of Asama, Banga and Utkala.

After the invasion of Mithila by the sultan of Johnpur, Delhi, and the disappearance of Shivasimha in 1429, Onibar rule grew weaker and the literary activity shifted to present-day Nepal.

The earliest reference to Maithili or Tirhutiya is in Amaduzzi's preface to Beligatti's Alphabetum Brammhanicum, published in 1771. This contains a list of Indian languages amongst which is 'Tourutiana.' Colebrooke's essay on the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages, written in 1801, was the first to describe Maithili as a distinct dialect.

Many devotional songs were written by vaisnava saints, including in the mid-17th century, Vidyapati and Govindadas. Mapati Upadhyaya wrote a drama titled Pārijātaharaṇa in Maithili. Professional troupes, mostly from dalit classes known as Kirtanias, the singers of bhajan or devotional songs, started to perform this drama in public gatherings and the courts of the nobles. Lochana (c. 1575 – c. 1660) wrote Rāgatarangni, a significant treatise on the science of music, describing the rāgas, tālas and lyrics prevalent in Mithila.

The Malla dynasty's mother tongue was Maithili, which spread far and wide throughout Nepal from the 16th to the 17th century. During this period, at least 70 Maithili dramas were produced. In the drama Harishchandranrityam by Siddhinarayanadeva (1620–57), some characters speak pure colloquial Maithili, while others speak Bengali, Sanskrit or Prakrit. The Nepal tradition may be linked with the Ankiya Nāta in Assam and Jatra in Odisha.

After the demise of Maheshwar Singh, the ruler of Darbhanga Raj, in 1860, the Raj was taken over by the British Government as regent. The Darbhanga Raj returned to his successor, Maharaj Lakshmishvar Singh, in 1898. The Zamindari Raj had a lackadaisical approach toward Maithili. The use of Maithili language was revived through personal efforts of MM Parameshvar Mishra, Chanda Jha, Munshi Raghunandan Das and others.

Publication of Maithil Hita Sadhana (1905), Mithila Moda (1906), and Mithila Mihir (1908) further encouraged writers. The first social organization, Maithil Mahasabha, was established in 1910 for the development of Mithila and Maithili. It blocked its membership for people outside from the Maithil Brahmin and Karna Kayastha castes. Maithil Mahasabha campaigned for the official recognition of Maithili as a regional language. Calcutta University recognized Maithili in 1917, and other universities followed suit.

Babu Bhola Lal Das wrote Maithili Grammar (Maithili Vyakaran). He edited a book Gadyakusumanjali and edited a journal Maithili.

In 1965, Maithili was officially accepted by Sahitya Academy, an organization dedicated to the promotion of Indian literature.

In 2002, Maithili was recognized on the VIII schedule of the Indian Constitution as a major Indian language; Maithili is now one of the 22 national languages of India.[6]

The publishing of Maithili books in Mithilakshar script was started by Acharya Ramlochan Saran.

Writing system

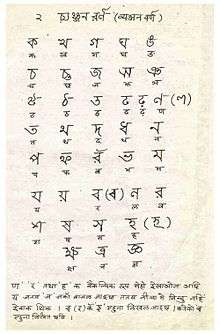

Maithili was traditionally written in the Maithili script, also known as Mithilakshar and Tirhuta. Devanagari script is most commonly used since the 20th century.[18]

The Tirhuta (Mithilakshar) and Kaithi scripts are both currently included in Unicode.

Maithili calendar

The Maithili calendar or Tirhuta Panchang (तिरहुता पंचांग / তিরহুতা পঞ্চাঙ্গ) is followed by the Maithili community of India and Nepal. It is one of the many Hindu calendars based on Bikram Sambat. It is a sidereal solar calendar in which the year begins on the first day of Baisakh month, i.e., Mesh Sankranti. This day falls on 13/14 April of the Georgian calendar. Pohela Baishakh Bangladesh and in Poschim Banga, Rangali Bihu in Assam, Puthandu in Tamil Nadu, and Vaishakhi in Punjab are observed on the same day. These festivals mark the beginning of new year in their respective regions.

| No. | Name | Maithili (Tirhuta) | Maithili (Devanagari) | Sanskrit | Days (Traditional Hindu sidereal solar calendar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baishakh | বৈসাখ | बैसाख | वैशाख | 30 / 31 |

| 2 | Jeth | জেঠ | जेठ | ज्येष्ठ | 31 / 32 |

| 3 | Asharh | আষাঢ় | आषाढ़ | आषाढ | 31 / 32 |

| 4 | Saon | সাৱোন | सावोन | श्रावण | 31 / 32 |

| 5 | Bhado | ভাদো | भादो | भाद्रपद,भाद्र,प्रोष्ठपद | 31 / 32 |

| 6 | Aasin | আসিন | आसिन | आश्विन | 31 / 30 |

| 7 | Katik | কাতিক | कातिक | कार्तिक | 29 / 30 |

| 8 | Agahan | অগহন | अगहन | अग्रहायण,मार्गशीर्ष | 29 / 30 |

| 9 | Poos | পূস | पूस | पौष | 29 / 30 |

| 10 | Magh | মাঘ | माघ | माघ | 29 / 30 |

| 11 | Fagun | ফাগুন | फागुन | फाल्गुन | 29 / 30 |

| 12 | Chait | চৈতি | चैति | चैत्र | 30 / 31 |

Literature

The most famous literary figure in Maithili is the poet Vidyapati (1350–1450), who wrote his poems in the language of the people, i.e., Maithili, at a time when state's official language was Sanskrit and Sanskrit was being used as a literary language. The use of Maithili, instead of Sanskrit, in literature became more common after Vidyapati.

The main characteristics of Magadhi Prakrit is to mutate 'r' into 's', the 'n' for n, of 'j' for 'y', of 'b' for 'y' In the edicts of Ashoka the change of 'r' to 'h' is established. Mahavir and Buddha delivered their sermons in the eastern languages. The secular use of language came mainly from the east as will be evident from the Prakritpainglam, a comprehensive work on Prakrit and Apabhramsa-Avahatta poetry. Jyotirishwar mentions Lorika. Vachaspati II in his Tattvachintamani and Vidyapati in his Danavakyavali have profusely used typical Maithili words of daily use.

The Maithili script, Mithilakshara or Tirhuta as it is popularly known, is of a great antiquity. The Lalitavistara mentions the Vaidehi script. Early in the latter half of the 7th century A.D., a marked change occurred in the northeastern alphabet, and the inscriptions of Adityasena exhibit this change for the first time. The eastern variety develops and becomes the Maithili script, which comes into use in Assam, Bengal and Nepal. The earliest recorded epigraphic evidence of the script is found in the Mandar Hill Stone inscriptions of Adityasena in the 7th century A.D.), now fixed in the Baidyanath temple of Deoghar.[20]

The Kamrupa dialect was originally a variety of eastern Maithili and it was the spoken Aryan language throughout the kingdom, which then included the Assam valley, North Bengal and the district of Purnea. The language of the Buddhist dohas is described as belonging to the mixed Maithili—Kamrupi language.[21]

Early Maithili Literature (ca. 700–1350 AD)

The period was of ballads, songs, and dohas. Some important Maithili writers of this era were:

- Kavi Kokil Pre-Jyotirishwar Vidyapati

- Jyotirishwar Thakur (1290–1350) whose Varnartnakar is the first prose and encyclopedia in northern Indian language.

Middle Maithili Literature (ca. 1350–1830 AD)

The period was of theatrical writings. Some important Maithili writers of this era were:

- Vidyapati (1350–1450)

- Srimanta Sankardeva (1449–1568)

- Govindadas

Modern Maithili Literature (1830 AD to date)

Modern Maithili came into its own after George Abraham Grierson, an Irish linguist and civil servant, tirelessly researched Maithili folklore and transcribed its grammar. Paul R. Brass wrote that "Grierson judged that Maithili and its dialects could fairly be characterized as the language of the entire population of Janakpur, Siraha, Saptari, Sarlahi, Darbhanga and Madhubani".[22]

In April 2010 a translation of the New Testament into Maithili was published by the Bible Society of India under joint copyright with Nepal Wycliffe Bible Translators.

The development of Maithili in the modern era was due to magazines and journals mainly concentrated at Janakpur. Some important writers of this era are:

- Acharya Ramlochan Saran (1889–1971)

- Baldev Mishra (1890–1975)[23]

- Prof.Krishna Kumar Jha 'Anveshak" Editor Maithili Darpan Magazine and author Mithila Anveshan

- Surendra Jha 'Suman' (1910–2002) represented Maithili in the Sahitya Akademi

- Radha Krishna Choudhary (1921–1985)

- Sudhanshu Shekhar Chaudhary (1920–1990) authored plays in Maithili and received the Sahitya Akademi Honour in 1981

- Jaykant Mishra (20 December 1922 – 3 February 2009) represented Maithili in the Sahitya Akademi

- Anant Bihari Lal Das “Indu” (1928–2010), awarded in 2007 by Sahitya Akademi

- Rajkamal Chaudhary (1929–1967)

- Binod Bihari Verma (1937–2003)

- Parichay Das [1964 ]

- Raman Jha 1957-

- Gajendra Thakur (1971– )

- Rambhadra (1933– )

- Rupesh Teoth

- Vinit Utpal

- Umesh Mandal

- Amarendra Yadav

- Shankardeo Jha

- Roshan Janakpuri

- Sumit Anand 1992-

See also

| Maithili edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Mithilakshar

- Languages of Nepal

- Languages of India

- Languages with official status in India

- List of Indian languages by total speakers

Bibliography

- George A. Grierson (1909). An Introduction to the Maithili dialect of the Bihari language as spoken in North Bihar. Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

- Ramawatar Yadav , Tribhvan University. Maithili Language and Linguistics: Some Background Notes (PDF). University of Cambridge.

References

- ↑ Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2000, Census of India, 2001

- ↑ http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/census/wphc/Nepal/Nepal-Census-2011-Vol1.pdf

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Maithili". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Maithili". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 Yadava, Y. P. (2013). Linguistic context and language endangerment in Nepal. Nepalese Linguistics 28: 262–274.

- 1 2 Singh, P., & Singh, A. N. (2011). Finding Mithila between India’s Centre and Periphery. Journal of Indian Law & Society 2: 147–181.

- 1 2 Sah, K. K. (2013). Some perspectives on Maithili. Nepalese Linguistics 28: 179–188.

- ↑ Government of Nepal (2007). Interim Constitution of Nepal 2007

- 1 2 3 Lewis, M. P. (ed.) (2009). Maithili Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- 1 2 Yadav, R. (1979). "Maithili language and Linguistics: Some Background Notes". Maithili Phonetics and Phonology (PDF). Doctoral Disseration, University of Kansas, Lawrence.

- ↑ Yadav, R. (1996). A Reference Grammar of Maithili. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, New York.

- ↑ Chatterji, S. K. (1926). The origin and development of the Bengali language. University Press, Calcutta.

- ↑ Brass, P. R. (2005). Language, Religion and Politics in North India. iUniverse, Lincoln, NE.

- ↑ Ray, K. K. (2009). Reduplication in Thenthi Dialect of Maithili Language. Nepalese Linguistics 24: 285–290.

- ↑ Yadav, R. (1992). "The Use of the Mother Tongue in Primary Education: The Nepalese Context" (PDF). Contributions to Nepalese Studies. 19 (2): 178–190.

- ↑ Asad, M. (2015). Reduplication in Modern Maithili. Language in India 15: 28–58.

- ↑ Choudhary, P.K. 2013. Causes and Effects of Super-stratum Language Influence, with Reference to Maithili. Journal of Indo-European Studies 41(3/4): 378–391.

- ↑ Pandey, A. (2009). Towards an Encoding for the Maithili Script in ISO/IEC 10646. University of Michigan, Michigan.

- ↑ Maithili Calendar, published from Darbhanga

- ↑ Choudhary, R. (1976). A survey of Maithili literature. Ram Vilas Sahu.

- ↑ Barua, K. L. (1966). Early history of Kamarupa. Lawyers Book Stall, Guwahati, India, 234. Page 318

- ↑ Brass, P. R. (1974). Language, Religion and Politics in North India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974. page 64

- ↑ Mishra, V. (1998). Makers of Indian Literature series (Maithili): Baldev Mishra. Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi. ISBN 81-260-0465-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maithili language. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Maithili phrasebook. |

- UCLA Language Materials Project : Maithili

- National Translation Mission's (NTM) Maithili Pages

- Videha Ist Maithili ejournal – ISSN 2229-547X

- Maithili Books

- Udbodhana Regd International e journal

- Birth place of Vidyapati