Magnetic stripe card

2.jpg)

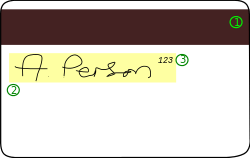

A magnetic stripe card is a type of card capable of storing data by modifying the magnetism of tiny iron-based magnetic particles on a band of magnetic material on the card. The magnetic stripe, sometimes called swipe card or magstripe, is read by swiping past a magnetic reading head. Magnetic stripe cards are commonly used in credit cards, identity cards, and transportation tickets. They may also contain an RFID tag, a transponder device and/or a microchip mostly used for business premises access control or electronic payment.

Magnetic recording on steel tape and wire was invented during World War II for recording audio. In the 1950s, magnetic recording of digital computer data on plastic tape coated with iron oxide was invented. In 1960 IBM used the magnetic tape idea to develop a reliable way of securing magnetic stripes to plastic cards,[1] under a contract with the US government for a security system. A number of International Organization for Standardization standards, ISO/IEC 7810, ISO/IEC 7811, ISO/IEC 7812, ISO/IEC 7813, ISO 8583, and ISO/IEC 4909, now define the physical properties of the card, including size, flexibility, location of the magstripe, magnetic characteristics, and data formats. They also provide the standards for financial cards, including the allocation of card number ranges to different card issuing institutions.

The magnetic stripe

Magnetic storage was known from World War II and computer data storage in the 1950s.[1]

In 1969 Forrest Parry, an IBM engineer, had the idea of securing a piece of magnetic tape, the predominant storage medium at the time, to a plastic card base. He became frustrated because every adhesive he tried produced unacceptable results. The tape strip either warped or its characteristics were affected by the adhesive, rendering the tape strip unusable. After a frustrating day in the laboratory, trying to get the right adhesive, he came home with several pieces of magnetic tape and several plastic cards. As he walked in the door at home, his wife Dorothea was ironing clothing. When he explained the source of his frustration: inability to get the tape to "stick" to the plastic in a way that would work, she suggested that he use the iron to melt the stripe on. He tried it and it worked.[2][3] The heat of the iron was just high enough to bond the tape to the card.

First magnetic striped plastic credit and badge access cards

The major development of the magnetic striped plastic card began in 1969 at the IBM Information Records Division (IRD) headquartered in Dayton N.J. In 1970 the marketing organization was transferred by IBM DPD back to the Information Records Division in order to begin sales and marketing strategies for the magnetically striped and encoded cards being developed.[4] It took almost two years for IBM IRD engineers to not only develop the process for reliably applying the magnetic stripe to plastic cards via a hot stamping method, but also develop the process for encoding the magnetic stripe utilizing the IBM Delta Distance C Optical Bar Code format.[5][6] This engineering effort resulted in IBM IRD producing the first magnetic striped plastic credit and ID cards used by banks, insurance companies, hospitals and many others. Another result of this project was that IBM IRD and IBM Data Processing Division announced on February 24, 1971 the first Magnetic Credit Card Service Center and the IBM 2730-1 Transaction Validation Terminal.[4] Arthur E. Hahn Jr.[7] was hired by IBM IRD in Dayton, N.J. on Aug 12, 1969 to head up this engineering effort. Other members of the group were David Morgan (Manager), Billy House (Software Developer), William Creeden (Programmer), and E. J. Gillen (Mechanical Engineering/Machining). They were given a recently announced IBM 360 Model 30 computer with 50k of RAM for control of the encoding/embossing of the Magnetic Stripe Cards.[8] The IBM 360 computer was for scientific/business applications so the IRD engineers first had to convert the 360 into a "process control computer" and then develop software and hardware around it. Due to the limited RAM the software was developed in 360 Assembler Language. This conversion enabled the 360 computer to monitor and control the entire production process the IRD engineers designed and built. The engineering design/build effort was carried out in a raised floor secured area of IBM IRD in Dayton, N.J. which was built specifically for the project. This tightly secured area with limited access was required because of the sensitivity of the data that would ultimately be used to encode and emboss the credit and ID cards.

Bar code encoding developments

The IRD engineers first had to develop a reliable process of hot stamping the magnetic stripe to the plastic cards. This was necessary in order to meet the close tolerances required to reliably encode and read the data on the Magnetic Stripe Cards by magnetic write/read heads. The magnetic stripe was encoded with a single track of data utilizing the IBM Delta Distance C Optical Bar Code format.[5][6] The Delta Distance C Optical Bar Code was developed by the IBM Systems Development Division working at Research Triangle Park in Raleigh North Carolina headed up by George J. Laurer. Other members of the group were N. Joseph Woodland, Paul McEnroe, Dr. Robert Evans, Bernard Silver, Art Hamburgen, Heard Baumeister and Bill Crouse.[5] The IBM group in Raleigh was competing with RCA, Litton-Zellweger and other companies who were working with the National Retail Merchants Association NRMA to develop a standard optical bar code to be used in the retail industry. NRMA wanted an optically readable code that could be printed on products allowing purchasers to rapidly “check out” at the new electronic cash register/checkout counters being developed. The code would also be used for production and inventory control of products. Of the many optical bar codes submitted to NRMA by IBM and other companies, NRMA finally selected the later version of the IBM bar code known as the Delta Distance D Optical Bar Code format. The Delta Distance C Code was an earlier version of the UPC Universal Product Code. The UPC code was selected in 1973 by NRMA as their standard and has become the World Wide Standard that we all know today as the UPC Uniform Product Code.[9]

The production process

In 1971, after the IBM IRD engineers completed the development and building phase of the project they began in 1969, they released the equipment to the IRD manufacturing group in Dayton N.J. to begin producing the plastic magnetic striped credit and ID cards. Because of the sensitivity of the customer data and the security requirements of banks, insurance companies and others, the manufacturing group decided to leave the entire line in the secured area where it was developed.

Banks, insurance companies, hospitals etc., supplied IBM IRD with “raw plastic cards” preprinted with their logos, contact information etc. They also supplied the data information which was to be encoded and embossed on the cards. This data was supplied to IRD on large 0.5 inch wide, 10.5 inch diameter IBM Magnetic Tape Reels which was the standard for computers at that time.[8] The manufacturing process started by first applying the magnetic stripe to the preprinted plastic cards via the hot stamping process developed by the IBM IRD engineers. This operation of applying the magnetic stripe to the plastic cards was done off line in another area of IBM IRD and not in the secured area. The cards were then brought into the secured area and placed in “hoppers” at the beginning of the production line. The tape reels containing the data were then installed on the modified IBM 360 computer prior to beginning the encoding, embossing and verification of the cards. After the 360 performed a check to verify that all systems and stations were loaded and ready to go, the computer began feeding the Magnetic Striped Plastic Cards from the hoppers at the front end of the production line down a motorized track. The entire operation was fully automated and controlled by the modified IBM 360 business computer. The line consisted of the following stations and operations:

- Plastic card feeder station: The cards were fed down a track in single file from card hoppers.

- Magnetic write/read encoding station: The IBM 360 computer sent over the data which was encoded on the magnetic stripe utilizing the IBM Delta Distance C Optical Bar Code format. The card passed under the read head and the encoded data was sent back to the 360 for verification.

- An embossing station: The IRD engineers purchased and modified a Data Card Corp embossing machine and interfaced it with the IBM 360 computer to emboss the cards.[8] The original design concept called for an Addressograph-Multigraph embossing machine, however, the IRD engineers quickly switched to a Data Card Corp embossing machine. Data Card Corp, a Minneapolis/St. Paul company had just developed the first electronically controlled embossing machine for plastic cards and effectively obsoleted all other mechanical operated embossers.

- A topping station: To highlight the embossing.

- An imprinter station: To imprint the embossing on an automatically fed paper roll.

- An optical reader station: To read the embossed information off the paper roll and feed it back to the 360 computer for verification.

- A one card rejection station: If either the encoding or embossing data on the card was not verified by the 360 computer, that one card was rejected. If both the encoded and embossed data was confirmed by the 360 computer, the card proceeded down the line.

- A mailer station: A mailer was printed with the name and address of the card holder along with the date and other relevant card information. These mailers were also preprinted and die cut by IRD according to the customers specs and logo requirements and were fed into the line out of boxes in a continuous fan feed method.

- A card insertion station: Here the card was automatically inserted onto the mailer.

- A bursting and folding station: Here the mailers were burst apart and then folded into a 3 fold packet that would fit into a business size envelope.

- An envelope printer/ insertion station: Here an envelope was printed with the name and address of the customer and the mailer containing the card was automatically inserted into the envelope and sealed.

This completed the manufacturing line for the magnetic striped encoded and embossed plastic credit and badge access cards. The envelopes were then taken to be posted and mailed directly to the customers of the companies who had ordered the cards from IRD.

What this small engineering group at IBM IRD and the IBM Bar Code development group in Raleigh accomplished in developing the first magnetic stripe credit and ID cards cannot be overstated. They laid the foundation for the entire magnetic stripe card industry that we know and use today through our use of credit cards, ATM cards, ID cards, hotel room and access cards, transportation tickets, and all the terminals and card readers that read the cards and enter the data into computers. Their developments resulted in every person having the ability to easily carry a card that connects them directly to computers with all the ramifications thereof.

Nether IBM nor anyone else applied for or received any patents pertaining to the magnetic stripe card, the delta-distance barcodes or even the Uniform Product Code (UPC). IBM felt that with an open architecture it would enhance the growth of the media thereby resulting in more IBM computers and associated hardware being sold. As with all new technologies, the magnetic stripe card developed and produced by IBM IRD with one track of encoded data using the Delta Distance C Bar Code format was quickly obsolete. Because of the electronic ATM/reservation/check out/and access systems that were rapidly developing, the banks, airlines and other industries required more encoded data. A wider magnetic stripe enabling multiple tracks of encoding along with new encoding standards was required.

The first US Patents for the ATM were granted in 1972[10] and 1973.[11]

Other groups within IBM and other companies continued on with expanding the work done by this small group of engineers at IBM IRD, however, the contributions that these IBM IRD engineers made to the development of the magnetic stripe card is analogous to the Wright Brother’s contribution to the airline industry of today.

Further developments and encoding standards

There were a number of steps required to convert the magnetic striped media into an industry acceptable device. These steps included:

- Creating the international standards for stripe record content, including which information, in what format, and using which defining codes.

- Field testing the proposed device and standards for market acceptance.

- Developing the manufacturing steps needed to mass-produce the large number of cards required.

- Adding stripe issue and acceptance capabilities to available equipment.

These steps were initially managed by Jerome Svigals of the Advanced Systems Division of IBM, Los Gatos, California from 1966 to 1975.

In most magnetic stripe cards, the magnetic stripe is contained in a plastic-like film. The magnetic stripe is located 0.223 inches (5.66 mm) from the edge of the card, and is 0.375 inches (9.52 mm) wide. The magnetic stripe contains three tracks, each 0.110 inches (2.79 mm) wide. Tracks one and three are typically recorded at 210 bits per inch (8.27 bits per mm), while track two typically has a recording density of 75 bits per inch (2.95 bits per mm). Each track can either contain 7-bit alphanumeric characters, or 5-bit numeric characters. Track 1 standards were created by the airlines industry (IATA). Track 2 standards were created by the banking industry (ABA). Track 3 standards were created by the Thrift-Savings industry.

Magstripes following these specifications can typically be read by most point-of-sale hardware, which are simply general-purpose computers that can be programmed to perform specific tasks. Examples of cards adhering to these standards include ATM cards, bank cards (credit and debit cards including Visa and MasterCard), gift cards, loyalty cards, driver's licenses, telephone cards, membership cards, electronic benefit transfer cards (e.g. food stamps), and nearly any application in which value or secure information is not stored on the card itself. Many video game and amusement centers now use debit card systems based on magnetic stripe cards.

Magnetic stripe cloning can be detected by the implementation of magnetic card reader heads and firmware that can read a signature of magnetic noise permanently embedded in all magnetic stripes during the card production process. This signature can be used in conjunction with common two factor authentication schemes utilized in ATM, debit/retail point-of-sale and prepaid card applications.[12]

Counterexamples of cards which intentionally ignore ISO standards include hotel key cards, most subway and bus cards, and some national prepaid calling cards (such as for the country of Cyprus) in which the balance is stored and maintained directly on the stripe and not retrieved from a remote database.

Magnetic stripe coercivity

.jpg)

Magstripes come in two main varieties: high-coercivity (HiCo) at 4000 Oe and low-coercivity (LoCo) at 300 Oe, but it is not infrequent to have intermediate values at 2750 Oe. High-coercivity magstripes require higher amount of magnetic energy to encode, and therefore are harder to erase. HiCo stripes are appropriate for cards that are frequently used, such as a credit card. Other card uses include time and attendance tracking, access control, library cards, employee ID cards and gift cards. Low-coercivity magstripes require a lower amount of magnetic energy to record, and hence the card writers are much cheaper than machines which are capable of recording high-coercivity magstripes. However, LoCo cards are much easier to erase and have a shorter lifespan. Typical LoCo applications include hotel room keys, time and attendance tracking, bus/transit tickets and season passes for theme parks. A card reader can read either type of magstripe, and a high-coercivity card writer may write both high and low-coercivity cards (most have two settings, but writing a LoCo card in HiCo may sometimes work), while a low-coercivity card writer may write only low-coercivity cards.

In practical terms, usually low coercivity magnetic stripes are a light brown color, and high coercivity stripes are nearly black; exceptions include a proprietary silver-colored formulation on transparent American Express cards. High coercivity stripes are resistant to damage from most magnets likely to be owned by consumers. Low coercivity stripes are easily damaged by even a brief contact with a magnetic purse strap or fastener. Because of this, virtually all bank cards today are encoded on high coercivity stripes despite a slightly higher per-unit cost.

Magnetic stripe cards are used in very high volumes in the mass transit sector, replacing paper based tickets with either a directly applied magnetic slurry or hot foil stripe. Slurry applied stripes are generally less expensive to produce and are less resilient but are suitable for cards meant to be disposed after a few uses.

Financial cards

There are up to three tracks on magnetic cards known as tracks 1, 2, and 3. Track 3 is virtually unused by the major worldwide networks, and often isn't even physically present on the card by virtue of a narrower magnetic stripe. Point-of-sale card readers almost always read track 1, or track 2, and sometimes both, in case one track is unreadable. The minimum cardholder account information needed to complete a transaction is present on both tracks. Track 1 has a higher bit density (210 bits per inch vs. 75), is the only track that may contain alphabetic text, and hence is the only track that contains the cardholder's name.

Track 1 is written with code known as DEC SIXBIT plus odd parity. The information on track 1 on financial cards is contained in several formats: A, which is reserved for proprietary use of the card issuer, B, which is described below, C-M, which are reserved for use by ANSI Subcommittee X3B10 and N-Z, which are available for use by individual card issuers:

Track 1, Format B:

- Start sentinel — one character (generally '%')

- Format code="B" — one character (alpha only)

- Primary account number (PAN) — up to 19 characters. Usually, but not always, matches the credit card number printed on the front of the card.

- Field Separator — one character (generally '^')

- Name — 2 to 26 characters

- Field Separator — one character (generally '^')

- Expiration date — four characters in the form YYMM.

- Service code — three characters

- Discretionary data — may include Pin Verification Key Indicator (PVKI, 1 character), PIN Verification Value (PVV, 4 characters), Card Verification Value or Card Verification Code (CVV or CVC, 3 characters)

- End sentinel — one character (generally '?')

- Longitudinal redundancy check (LRC) — it is one character and a validity character calculated from other data on the track.

Track 2: This format was developed by the banking industry (ABA). This track is written with a 5-bit scheme (4 data bits + 1 parity), which allows for sixteen possible characters, which are the numbers 0-9, plus the six characters : ; < = > ? . The selection of six punctuation symbols may seem odd, but in fact the sixteen codes simply map to the ASCII range 0x30 through 0x3f, which defines ten digit characters plus those six symbols. The data format is as follows:

- Start sentinel — one character (generally ';')

- Primary account number (PAN) — up to 19 characters. Usually, but not always, matches the credit card number printed on the front of the card.

- Separator — one char (generally '=')

- Expiration date — four characters in the form YYMM.

- Service code — three digits. The first digit specifies the interchange rules, the second specifies authorisation processing and the third specifies the range of services

- Discretionary data — as in track one

- End sentinel — one character (generally '?')

- Longitudinal redundancy check (LRC) — it is one character and a validity character calculated from other data on the track. Most reader devices do not return this value when the card is swiped to the presentation layer, and use it only to verify the input internally to the reader.

Service code values common in financial cards:

First digit

- 1: International interchange OK

- 2: International interchange, use IC (chip) where feasible

- 5: National interchange only except under bilateral agreement

- 6: National interchange only except under bilateral agreement, use IC (chip) where feasible

- 7: No interchange except under bilateral agreement (closed loop)

- 9: Test

Second digit

- 0: Normal

- 2: Contact issuer via online means

- 4: Contact issuer via online means except under bilateral agreement

Third digit

- 0: No restrictions, PIN required

- 1: No restrictions

- 2: Goods and services only (no cash)

- 3: ATM only, PIN required

- 4: Cash only

- 5: Goods and services only (no cash), PIN required

- 6: No restrictions, use PIN where feasible

- 7: Goods and services only (no cash), use PIN where feasible

United States and Canada driver's licenses

The data stored on magnetic stripes on American and Canadian driver's licenses is specified by the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators. Not all states and provinces use a magnetic stripe on their driver's licenses. For a list of those that do, see the AAMVA list.[13][14]

The following data is stored on track 1:[15]

- Start Sentinel - one character (generally '%')

- State or Province - two characters

- City - variable length (seems to max out at 13 characters)

- Field Separator - one character (generally '^') (absent if city reaches max length)

- Last Name - variable length

- Field Separator - one character (generally '$')

- First Name - variable length

- Field Separator - one character (generally '$')

- Middle Name - variable length

- Field Separator - one character (generally '^')

- Home Address (house number and street) - variable length

- Field Separator - one character (generally '^')

- Unknown - variable length

- End Sentinel - one character (generally '?')

The following data is stored on track 2:

- ISO Issuer Identifier Number (IIN) - 6 digits

- Drivers License / Identification Number - 13 digits

- Field Separator — generally '='

- Expiration Date (YYMM) - 4 digits

- Birth date (YYYYMMDD) - 8 digits

- DL/ID# overflow- 5 digits (If no information is used then a field separator is used in this field.)

- End Sentinel - one character ('?')

The following data is stored on track 3:

- Template V#

- Security V#

- Postal Code

- Class

- Restrictions

- Endorsements

- Sex

- Height

- Weight

- Hair Color

- Eye Color

- ID#

- Reserved Space

- Error Correction

- Security

Note: Each state has a different selection of information they encode, not all states are the same. Note: Some states, such as Texas,[16] have laws restricting the access and use of electronically readable information encoded on driver's licenses or identification cards under certain circumstances.

Other card types

Smart cards are a newer generation of card that contain an integrated circuit. Some smart cards have metal contacts to electrically connect the card to the reader, and contactless cards use a magnetic field or radio frequency (RFID) for proximity reading.

Hybrid smart cards include a magnetic stripe in addition to the chip — this is most commonly found in a payment card, so that the cards are also compatible with payment terminals that do not include a smart card reader.

Cards with all three features: magnetic stripe, smart card chip, and RFID chip are also becoming common as more activities require the use of such cards.[17]

Vulnerabilities

DEF CON 24

During DEF CON[18] 24, Weston Hecker presented Hacking Hotel Keys, and Point Of Sales Systems. In the talk, he described the way mag-strip cards function and what they are composed of. He then went on to use Samy Kamkar's Mag-Spoof software[19], an Arduino, and other parts, to pull admin access from hotel keys, via maids walking by. He further used this method to explain how to use admin keys from POS systems on other systems, effectively giving you access to any system with a mag reader enabled, giving you access to run root commands. This could be used to, for example to refund transactions to a separate card, siphoning money to the hacker, or send all rewards points at stores to your card(s).

See also

- Access badge

- Access control

- Common Access Card

- Credential

- Credit card number

- Forrest Parry, the IBM engineer who invented the magnetic stripe card

- Identity document

- ID card printer

- Keycard

- MetroCard (New York City)

- Photo identification

- Physical security

- Proximity card

- Security

- Security engineering

- Smart card

- Stored-value card

References

- 1 2 Jerome Svigals, The long life and imminent death of the mag-stripe card, IEEE Spectrum, June 2012, p. 71

- ↑ "IBM100 - Click on "View all icons". Click on 8th row from the bottom titled "Magnetic Stripe Technology"". 2011-02-03. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ "Article on Forrest Parry, pages 3-4" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- 1 2 "IBM Archives: DPD chronology - page 4". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- 1 2 3 "Who Made That Universal Product Code". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- 1 2 "IBM100 - UPC". 03.ibm.com. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ Archived September 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "IBM100 - System 360". 03.ibm.com. 1964-04-07. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ "Retail Identification History Museum History of the UPC". Idhistory.com. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 3,685,690, "Credit card automatic currency dispenser"; Thomas Barnes, George Chastain, and Marion Karecki; issued August 22, 1972

- ↑ U.S. Patent 3,761,682, "Credit card automatic currency dispenser"; Thomas Barnes, George Chastain, and Don Wetzel; issued September 25, 1973

- ↑ "Welcome to MagnePrint®: What is MagnePrint?". Magneprint.com. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ↑ "ID Security Technologies". AAMVA. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ Archived December 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 2010 AAMVA DL/ID Card Design Standard Ver 1.0, Annex F.6, Aamva.org, June 2010, retrieved 2010-08-09

- ↑ "Texas statutes, section 521.126, restricting use of electronically readable information from driver's licenses or personal identification certificates". Texas Legislature Online, State of Texas. June 2015. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ↑ "ID Card Supply Now Offers Triple-Secure ID Cards With Magnetic Strip, RFID and Smart Chip - Press Release". Digital Journal. 2014-07-09. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ↑ "DEF CON". Wikipedia. 2016-11-05.

- ↑ "Samy Kamkar: MagSpoof - credit card/magstripe spoofer". samy.pl. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

External links

- Magnetic Stripe Formats

- A brief comparison of Mag stripe and RFID technology (2012)

- A Brief History of Reprogrammable Card Technology (2012)

- Magnetic Developer and Magnetic Encoding Standards