Mackenzie River

| Mackenzie River (Deh-Cho, Kuukpak) | |

The Mackenzie River in August 2009 | |

| Name origin: Alexander Mackenzie, explorer | |

| Country | Canada |

|---|---|

| Region | Yukon, Northwest Territories |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Liard River, Keele River, Arctic Red River, Peel River |

| - right | Great Bear River |

| Cities | Fort Providence, Fort Simpson, Wrigley, Tulita, Norman Wells |

| Source | Great Slave Lake |

| - location | Fort Providence |

| - elevation | 156 m (512 ft) |

| - coordinates | 61°12′15″N 117°22′31″W / 61.20417°N 117.37528°W |

| Mouth | Arctic Ocean |

| - location | Beaufort Sea, Inuvik Region |

| - elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| - coordinates | 68°56′23″N 136°10′22″W / 68.93972°N 136.17278°WCoordinates: 68°56′23″N 136°10′22″W / 68.93972°N 136.17278°W |

| Length | 1,738 km (1,080 mi) |

| Basin | 1,805,200 km2 (696,992 sq mi) [1] |

| Discharge | for mouth; max and min at Arctic Red confluence |

| - average | 9,910 m3/s (349,968 cu ft/s) [2] |

| - max | 31,800 m3/s (1,123,000 cu ft/s) [3] |

| - min | 2,130 m3/s (75,220 cu ft/s) |

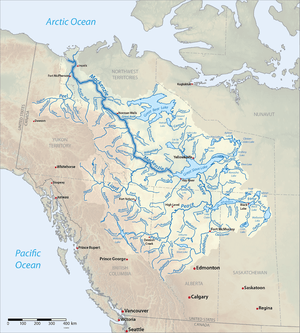

Map of the Mackenzie River watershed | |

The Mackenzie River (Slavey language: Deh-Cho, big river or Inuvialuktun: Kuukpak, great river) is the largest and longest river system in Canada, and is exceeded only by the Mississippi River system in North America. It flows through a vast, isolated region of forest and tundra entirely within the country's Yukon and Northwest Territories, although its many tributaries reach into four other Canadian provinces and territories. The river's mainstem runs 1,738 kilometres (1,080 mi) in a northerly direction to the Arctic Ocean, draining a vast area nearly the size of Indonesia. It is the largest river flowing into the Arctic from North America, and with its tributaries is one of the longest rivers in the world.

Course

Rising out of the marshy western end of Great Slave Lake, the Mackenzie River flows generally west-northwest for about 300 km (190 mi), passing the hamlet of Fort Providence. At Fort Simpson it is joined by the Liard River, its largest tributary, then swings towards the Arctic, paralleling the Franklin Mountains as it receives the North Nahanni River. The Keele River enters from the left about 100 km (62 mi) above Tulita, where the Great Bear River joins the Mackenzie. Just before crossing the Arctic Circle, the river passes Norman Wells, then continues northwest to merge with the Arctic Red and Peel rivers. It finally empties into the Beaufort Sea, part of the Arctic Ocean, through the vast Mackenzie Delta.[2][4][5]

Most of the Mackenzie River is a broad, slow-moving waterway; its elevation drops just 156 metres (512 ft) from source to mouth.[6] It is a braided river for much of its length, characterized by numerous sandbars and side channels. The river ranges from 2 to 5 km (1.2 to 3.1 mi) wide and 8 to 9 m (26 to 30 ft) deep in most parts, and is thus easily navigable except when it freezes over in the winter. However, there are several spots where the river narrows to less than half a kilometre (0.3 mi) and flows quickly, such as at the Sans Sault Rapids at the confluence of the Mountain River and "The Ramparts", a 40 m (130 ft) deep canyon south of Fort Good Hope.[7][8]

Watershed

At 1,805,200 square kilometres (697,000 sq mi), the Mackenzie River's watershed or drainage basin is the largest in Canada, encompassing nearly 20% of the country.[1] From its farthest headwaters at Thutade Lake in the Omineca Mountains to its mouth, the Mackenzie stretches for 4,241 km (2,635 mi) across western Canada, making it the longest river system in the nation and the thirteenth longest in the world.[1] The river discharges more than 325 cubic kilometres (78 cu mi) of water each year, accounting for roughly 11% of the total river flow into the Arctic Ocean.[9][10] The Mackenzie's outflow holds a major role in the local climate above the Arctic Ocean with large amounts of warmer fresh water mixing with the cold seawater.[2]

Many major watersheds of North America border on the drainage of the Mackenzie River. Much of the western edge of the Mackenzie basin runs along the Continental Divide. The divide separates the Mackenzie watershed from that of the Yukon River and its headstreams the Pelly and Stewart rivers, which flow to the Bering Strait; and the Fraser River and Columbia River systems, both of which run to the Pacific Ocean.[11] Lowland divides in the north distinguish the Mackenzie basin from those of the Anderson, Horton, Coppermine and Back Rivers – all of which empty into the Arctic. Eastern watersheds bordering on that of the Mackenzie include those of the Thelon and Churchill Rivers, both of which flow into Hudson Bay. On the south, the Mackenzie watershed borders that of the North Saskatchewan River, part of the Nelson River system, which empties into Hudson Bay after draining much of south-central Canada.[4][11]

Through its many tributaries, the Mackenzie River basin covers portions of five Canadian provinces and territories – British Columbia (BC), Alberta, Saskatchewan, Yukon, and Northwest Territories. The two largest headwaters forks, the Peace and Athabasca Rivers,[12] drain much of the central Alberta prairie and the Rocky Mountains in northern BC then combine into the Slave River at the Peace-Athabasca Delta near Lake Athabasca, which also receives runoff from northwestern Saskatchewan.[13] The Slave is the primary feeder of Great Slave Lake (contributing about 77% of the water); other inflows include the Taltson, Lockhart and Hay Rivers, the latter of which also extends into Alberta and BC.[14] Direct tributaries of the Mackenzie from the west such as the Liard and Peel Rivers carry runoff from the mountains of the eastern Yukon.[15]

The eastern portion of the Mackenzie basin is dominated by vast reaches of lake-studded boreal forest and includes many of the largest lakes in North America. By both volume and surface area, Great Bear Lake is the biggest in the watershed and third largest on the continent, with a surface area of 31,153 km2 (12,028 sq mi) and a volume of 2,236 km3 (536 cu mi).[16] Great Slave Lake is slightly smaller, with an area of 28,568 km2 (11,030 sq mi) and containing 2,088 km3 (501 cu mi) of water, although it is significantly deeper than Great Bear.[14] The third major lake, Athabasca, is less than a third that size with an area of 7,800 km2 (3,000 sq mi).[13] Six other lakes in the watershed cover more than 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi), including the Williston Lake reservoir, the second-largest artificial lake in North America, on the Peace River.[2]

With an average annual flow of 9,910 m3/s (350,000 cu ft/s), the Mackenzie River has a smaller discharge than the St Lawrence but is the fourteenth largest in the world in this respect.[17] About 60% of the water comes from the western half of the basin, which includes the Rocky, Selwyn, and Mackenzie mountain ranges out of which spring major tributaries such as the Peace and Liard Rivers, which contribute 23% and 27% of the total flow, respectively. In contrast the eastern half, despite being dominated by marshland and large lakes, provides only about 25% of the Mackenzie's discharge.[18] During peak flow in the spring, the difference in discharge between the two halves of the watershed becomes even more marked. While large amounts of snow and glacial melt dramatically drive up water levels in the Mackenzie's western tributaries, large lakes in the eastern basin retard springtime discharges. Breakup of ice jams caused by sudden rises in temperature – a phenomenon especially pronounced on the Mackenzie – further exacerbate flood peaks. In full flood, the Peace River can carry so much water that it inundates its delta and backs upstream into Lake Athabasca, and the excess water can only flow out after the Peace has receded.[19]

Geology

As recently as the end of the last glacial period eleven thousand years ago the majority of northern Canada was buried under the enormous continental Laurentide ice sheet. The tremendous erosive powers of the Laurentide and its predecessors, at maximum extent, completely buried the Mackenzie River valley under thousands of meters of ice and flattened the eastern portions of the Mackenzie watershed. When the ice sheet receded for the last time, it left a 1,100 km (680 mi)-long postglacial lake called Lake McConnell, of which Great Bear, Great Slave and Athabasca Lakes are remnants.[16][20] Significant evidence exists that roughly 13,000 years ago, the channel of the Mackenzie was scoured by one or more massive glacial lake outburst floods unleashed from Lake Agassiz, formed by melting ice west of the present-day Great Lakes. At its peak, Agassiz had a greater volume than all present-day freshwater lakes combined.[21] This is believed to have disrupted currents in the Arctic Ocean and led to an abrupt 1,300-year-long cold temperature shift called the Younger Dryas.[22]

Ecology

The Mackenzie River's watershed is considered one of the largest and most intact ecosystems in North America, especially in the north. Approximately 63% of the basin – 1,137,000 km2 (439,000 sq mi) – is covered by forest, mostly boreal, and wetlands comprise some 18% of the watershed – about 324,900 km2 (125,400 sq mi). More than 93% of the wooded areas in the watershed are virgin forest. There are fifty-three fish species in the basin, none of them endemic.[23] Most of the aquatic species in the Mackenzie River are descendants of those of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. This anomaly is believed to have been caused by hydrologic connection of the two river systems during the Ice Ages by meltwater lakes and channels.[24]

Fish in the Mackenzie River proper include the northern pike, some minnows, and lake whitefish, and the river's shores are lined with sparse vegetation like dwarf birch and willows, as well as numerous peat bogs. Further south the tundra vegetation transitions to black spruce, aspen and poplar forest. Overall, the northern watershed is not very diverse ecologically, due to its cold climate – permafrost underlies about three-quarters of the watershed, reaching up to 100 m (330 ft) deep in the delta region[2] – and meager to moderate rainfall, amounting to about 410 millimetres (16 in) over the basin as a whole.[25] The southern half of the basin, in contrast, includes larger reaches of temperate and alpine forests as well as fertile floodplain and riparian habitat, but is actually home to fewer fish species due to large rapids on the Slave River preventing upstream migration of aquatic species.[26]

Migratory birds use the two major deltas in the Mackenzie River basin – the Mackenzie Delta and the inland Peace-Athabasca Delta – as important resting and breeding areas. The latter is located at the convergence of four major North American migratory routes, or flyways.[27] As recently as the mid-twentieth century, more than 400,000 birds passed through during the spring and up to a million in autumn. Some 215 bird species in total have been catalogued in the delta, including endangered species such as the whooping crane, peregrine falcon and bald eagle. The construction of the W.A.C. Bennett Dam on the Peace River has reduced the seasonal variations of water levels in the delta, causing damage to its ecosystems. Populations of migratory birds in the area have steadily declined since the 1960s.[28]

History

The Mackenzie (previously Disappointment) River was named after Scottish explorer Alexander Mackenzie, who travelled the river in the hope it would lead to the Pacific Ocean, but instead reached its mouth on the Arctic Ocean on 14 July 1789. No European reached its mouth again until Sir John Franklin on 16 August 1825. The following year he traced the coast west until blocked by ice while John Richardson followed the coast east to the Coppermine River. In 1849 William Pullen reached the Mackenzie from Bering Strait.

The Royal Canadian Mint honoured the 200th anniversary of the naming of the Mackenzie River with the issue of a silver commemorative dollar in 1989.

In 1997, a cultural landscape along the section of the Mackenzie River at Tsiigehtchic was designated the Nagwichoonjik (Mackenzie River) National Historic Site of Canada due to its cultural, social and spiritual significance to the Gwichya Gwich'in.[29]

In 2008, Canadian and Japanese researchers extracted a constant stream of natural gas from a test project at the Mallik methane hydrate field in the Mackenzie Delta. This was the second such drilling at Mallik: the first took place in 2002 and used heat to release methane. In the 2008 experiment, researchers were able to extract gas by lowering the pressure, without heating, requiring significantly less energy.[30] The Mallik gas hydrate field was first discovered by Imperial Oil in 1971–1972.[31]

Human use

As of 2001, approximately 397,000 people lived in the Mackenzie River basin – representing only 1% of Canada's population. Ninety percent of these people lived in the Peace and Athabasca River drainage areas, and mainly in Alberta. The cold northern permafrost regions beyond the Arctic Circle are very sparsely populated, mainly by indigenous peoples.[2] As a result, much of the Mackenzie watershed consists of unbroken wilderness and human activities presently have little influence on water quality or quantity in the basin's major rivers.[32] Perhaps the heaviest use of the watershed is in resource extraction – oil and gas in central Alberta, lumber in the Peace River headwaters, uranium in Saskatchewan, gold in the Great Slave Lake area and tungsten in the Yukon. Especially in the case of oil, these activities are beginning to pose a threat to riverine ecology in the headwaters of the Mackenzie River.[2][33]

During the ice-free season, the Mackenzie is a major transportation link through the vast wilderness of northern Canada, linking the numerous scattered and isolated communities along its course. Canada's northernmost major railhead is located at the town of Hay River, on the south shore of Great Slave Lake. Goods shipped there by train and truck are loaded onto barges of the Inuit-owned Northern Transportation Company.[34] Barge traffic travels the entire length of the Mackenzie in long "trains" of up to fifteen vessels pulled by tugboats, with the sole exception being in a few of the river's narrows, where the barges are uncoupled and towed one by one through difficult stretches. Goods are shipped as far as the town of Tuktoyaktuk on the eastern end of the Mackenzie Delta. From there they are further distributed among communities along Canada's Arctic coast and the numerous islands north of it.[35] During the winter, the frozen channel of the Mackenzie River, especially in the delta region, is crisscrossed with ice roads served by dogsleds and snowmobiles.[36]

Although the entire main stem of the Mackenzie River is undammed, many of its tributaries and headwaters have been developed for hydroelectricity production, flood control and agricultural purposes. The W.A.C. Bennett Dam and Peace Canyon Dam on the upper Peace River were completed in 1968 and 1980 for power generation purposes. The two dams, both owned by BC Hydro, have a combined capacity of more than 3,400 megawatts (MW).[37][38] The reservoir of W.A.C. Bennett – Williston Lake – is the largest body of fresh water in BC and the ninth largest man-made lake in the world, with a volume of 70.3 km3 (57,000,000 acre·ft).[39] Williston's additional purpose of flood control has led to reduced flooding in the Peace River valley, the Peace-Athabasca Delta, and the Slave River, which while providing for better farming conditions, has had significant impacts on wildlife and riparian communities. The decrease in annual flow fluctuations has had impacts as far downstream as the main stem of the Mackenzie.[40][41]

Agriculture in the Mackenzie River basin is mainly concentrated in the southern portion of the watershed, namely the valleys of the Peace and Athabasca Rivers. The valley of the former river is considered to be some of the best northern farmland in Canada. These conditions are expected to be improved even more by recent trends in climate change, such as warmer temperatures and a longer growing season.[42][43] It is even said that "there is enough agricultural capability in the Peace River Valley to provide vegetables to all of northern Canada".[44] However, reaches of the Peace River Valley are threatened with flooding by the proposed Site C Dam, which would generate enough electricity to power about 460,000 households. Site C has been the center of a protracted and ongoing environmental battle since the 1970s, and a decision has not yet been reached as to whether or not to build the dam.[44][45]

Site C is not the only proposed water project in the Mackenzie basin. A potential US$1 billion run-of-the-river hydroelectricity station on the Slave River would generate at least 1,350 MW of power.[46][47] Some tentative proposals have gone as far as to include dams on the main stem of the Mackenzie itself.[48] By far the largest engineering project ever slated for the Mackenzie River was the North American Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA), a vast series of dams, tunnels and reservoirs designed to move 150 km3 (120,000,000 acre·ft) of Arctic meltwater to southern Canada, the western United States and Mexico. The system would involve building massive dams on the Liard, Mackenzie, Peace, Columbia, and Fraser rivers, then pumping water into a 650 km (400 mi) long reservoir in the Rocky Mountain Trench. The water would then flow by gravity to irrigate more than 220,000 km2 (85,000 sq mi) in the three countries and generate more than 50,000 MW of surplus energy.[49] First proposed in the 1950s, the project's estimated cost has since risen to over $200 billion. Because of its massive cost and environmental impacts, it is considered unlikely ever to be implemented.[50]

Tributaries

Largest

| Tributary | Length | Watershed | Discharge | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km | mi | km2 | sq mi | m3/s | cu ft/s | |

| Liard River | 1,115 | 693 | 277,100 | 106,989 | 2,434 | 85,960 |

| North Nahanni River | 200 | 124 | ||||

| Root River | 220 | 138 | ||||

| Redstone River | 289 | 180 | 16,400 | 6,332 | 417 | 14,726 |

| Keele River | 410 | 255 | 19,000 | 7,340 | 600 | 21,200 |

| Great Bear River | 113 | 70 | 156,500 | 60,425 | 528 | 18,646 |

| Mountain River | 370 | 230 | 13,500 | 5,212 | 123 | 4,344 |

| Arctic Red River | 500 | 311 | 22,000 | 8,494 | 161 | 5,690 |

| Peel River | 580 | 360 | 28,400 | 10,965 | 689 | 24,332 |

Full list

See also

- List of rivers of Canada

- List of rivers of the Northwest Territories

- Peace River Country

- Steamboats of the Mackenzie River

- Peel Watershed

Works cited

- Hodgins, Bruce W.; Hoyle, Gwyneth (1994). Canoeing north into the unknown: a record of river travel, 1874 to 1974. Dundurn Press. ISBN 0-920474-93-4.

- Pielou, E.C. (1991). After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-66812-6.

References

- 1 2 3 "Rivers". The Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Whole Basin overview" (PDF). Mackenzie River Basin: State of the Aquatic Ecosystem Report 2003. Saskatchewan Watershed Authority. pp. 15–56. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "MAGS: Daily Discharge Measurements". University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- 1 2 NRCAN Topo Maps for Canada (Map). Cartography by Natural Resources Canada. ACME Mapper. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Hodgins and Hoyle, p. 135

- ↑ "Mackenzie River: Physical Features". Encyclopaedia Britannica (1995 edition). University of Valencia. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "Mackenzie River: The Lower Course". Encyclopaedia Britannica (1995 edition). University of Valencia. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Hebert, Paul D. N. (2008-11-18). "Mackenzie River, Canada". Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "Mackenzie River Basin". Conservation. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Arnell, Nigel W. (2005-04-08). "Implications of climate change for freshwater inflows to the Arctic Oceans" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. Far Eastern Federal University. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- 1 2 Watersheds (Map). Cartography by CEC, Atlas of Canada, National Atlas, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC). Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ Marsh, James. "Mackenzie River". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion Institute. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- 1 2 Muzik, I. (1991). "Hydrology of Lake Athabasca" (PDF). Hydrology of Natural and Manmade Lakes. International Association of Hydrological Sciences. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- 1 2 "Great Slave Sub-basin" (PDF). Mackenzie River Basin: State of the Aquatic Ecosystem Report 2003. Saskatchewan Watershed Authority. pp. 143–168. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Major Drainage Areas of the Yukon Territory (Map). Cartography by Yukon Environment Geomatics. Yukon Environment. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- 1 2 "Great Bear Lake". World Lakes Database. International Lake Environment Committee Foundation. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "Water Sources: Rivers". Environment Canada. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Woo, Ming-Ko; Thorne, Robin (2003-03-04). "Streamflow in the Mackenzie Basin, Canada" (PDF). Arctic Institute of North America. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "The Peace-Athabasca Delta". Northern River Basins Study Final Report. Government of Alberta. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ Pielou, p. 193

- ↑ Schiermeier, Quirin (2010-03-31). "River reveals chilling tracks of ancient flood". Naturenews. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ↑ "The Younger Dryas". NOAA Paleoclimatology. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- ↑ "Mackenzie Watershed". EarthTrends: Watersheds of the World. World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Pielou, p. 190-191

- ↑ Burridge, Mary; Mandrak, Nicholas (2011-08-16). "105: Lower Mackenzie". Freshwater Ecoregions of the World. World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Burridge, Mary; Mandrak, Nicholas (2011-08-16). "104: Upper Mackenzie". Freshwater Ecoregions of the World. World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Peace-Athabasca Delta: Tar Sands Oil Expansion Threatens America's Premier Nesting Ground". Save BioGems. Natural Resources Defense Council. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Peace-Athabasca Delta". Important Bird Areas. Bird Studies Canada. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Nagwichoonjik (Mackenzie River) National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ Thomas, Brodie (2008-03-31). "Researchers extract methane gas from under permafrost". Northern News Services Online. Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ "Geological Survey of Canada, Mallik 2002". Natural Resources Canada. 2007-12-20. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ "Mackenzie River Watershed". Boreal Songbird Initiative. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "Northern Lifeblood: Empowering Northern Leaders to Protect the Mackenzie River Basin from the Risks of Oil Sands Development" (PDF). Pembina Institute. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ "What does North America look like to Canada's Northern Transportation Company?". Arctic Economics. 2008-06-12. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Mackenzie River: Barging ahead – The North's Native-owned transportation service". Canadian Council for Geographic Education. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Jozic, Jennifer. "Transportation in the North". Northern Research Portal. University of Saskatchewan. p. 3. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "40 Years On: The Story of the W.A.C. Bennett Dam". Hudson's Hope Museum. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Site C Dam". Watershed Sentinel. 2008. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Williston". BC Hydro. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Williston Lake". World Lakes Database. International Lake Environment Committee. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Flooding in the Peace-Athabasca Delta". Regional Aquatics Monitoring Program. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Media Release: Significant BC food source might go under water" (PDF). It's Our Valley. 2010-04-09. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Feinstein, Asa (February 2010). Churchill, Brian; Rowan, Arnica, eds. "BC's Peace River Valley and Climate Change: The Role of the Valley's Forests and Agricultural Land in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation" (PDF). It's Our Valley. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- 1 2 "Peace River Valley: Habitat for biodiversity, food security for British Columbia". The British Columbia Environmental Network. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Fawcett, Max (2010-04-05). "The Case against the Site C Dam: A reporter's Peace River journey against a powerful current of dubious assumptions and official spin. First of five parts this week.". The Tyee. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Slave River hydro project mixed". CBC News. 2010-10-18. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Jaque, Dom (2009-03-12). "Proposed Slave River Hydro Project Update" (PDF). Alberta Whitewater Association. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ "Some Canadian rivers at risk of drying up". WWF Global. World Wildlife Fund. 2009-10-15. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ LaRouche, Lyndon H. (January 1988). "The Outline of NAWAPA". The Schiller Institute. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- ↑ Nelson, Barry (2009-12-04). "The Rip Van Winkle of Water Projects – NAWAPA Reemerges after a 50 Year Slumber". Switchboard. Natural Resources Defense Council. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mackenzie River. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Mackenzie. |

- Information and a map of the Mackenzie's watershed

- Canadian Council for Geographic Education page with a series of articles on the history of the Mackenzie River.

- Atlas of Canada's page devoted to Arctic rivers of Canada.

- MAGS: Daily Discharge Measurements.