Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson served as the 36th President of the United States from 1963 to 1969. Johnson assumed the office after serving as the 37th Vice President of the United States under President John F. Kennedy, who was assassinated in 1963. Johnson was a Democrat from Texas who had previously served as Senate Majority Leader. After succeeding Kennedy, Johnson ran for a full term in the 1964 election, winning by a landslide over Republican opponent Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater. Johnson's presidency marked the high tide of modern liberalism in the United States, as Johnson expanded upon the New Deal with the Great Society.

Johnson's Great Society created Medicare and Medicaid, defended civil rights, and promoted federal spending on education, the arts, urban and rural development, public services, and a "War on Poverty". Assisted in part by a growing economy, the War on Poverty helped millions of Americans rise above the poverty line during Johnson's presidency.[1] Civil rights bills signed by Johnson banned racial discrimination in voting, public facilities, housing, and the workplace. With the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the country's immigration system was reformed and all racial origin quotas were removed (replaced by national origin quotas).

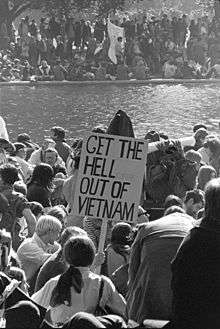

Johnson's popularity waned as other issues came to the fore. Johnson pursued a policy of containment in Vietnam, hoping to stop the spread of Communism into Southeast Asia during the Cold War. The number of American military personnel in Vietnam increased dramatically, from 16,000 advisors in non-combat roles in 1963,[2] to 550,000 in early 1968, many in combat roles. Growing unease with the war stimulated a large, angry antiwar movement based especially on university campuses in the U.S. and abroad.[3] Johnson faced further troubles when summer riots broke out in most major cities after 1965, and crime rates soared, as his opponents raised demands for "law and order" policies. While he began his presidency with widespread approval, support for Johnson declined as the public became upset with both the war and the growing violence at home. The Democratic Party factionalized as antiwar elements denounced Johnson, and Johnson ended his bid for renomination after a disappointing finish in the New Hampshire primary.

Major acts as president

|

Domestic Policy Actions

|

Foreign Policy Actions

Supreme Court nominations

|

Succession

President John F. Kennedy, in office since 1961, was assassinated in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963. Johnson was sworn in as president on the Air Force One plane in Dallas just 2 hours and 8 minutes after Kennedy's assassination. Johnson was sworn in by U.S. District Judge Sarah T. Hughes, a family friend. In the rush, a Bible was not at hand, so Johnson took the oath of office using a Roman Catholic missal from President Kennedy's desk.[4] Cecil Stoughton's iconic photograph of Johnson taking the presidential oath of office as Mrs. Kennedy looks on is the most famous photo ever taken aboard a presidential aircraft.[5][6]

Johnson was convinced of the need to make an immediate transition of power after the assassination to provide stability to a grieving nation in shock. He and the Secret Service were concerned that he could also be a target of a conspiracy, and felt compelled to rapidly return to Washington, D.C.. Johnson's rush was greeted by some with assertions that Johnson was in too much haste to assume power.[7]

In the days following the assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson made an address to Congress, saying that "No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the Civil Rights Bill for which he fought so long."[8] The wave of national grief following the assassination gave enormous momentum to Johnson's promise to carry out Kennedy's plans and his policy of seizing Kennedy's legacy to give momentum to his legislative agenda. On November 29, 1963 just one week after Kennedy's assassination, Johnson issued an executive order to rename NASA's Apollo Launch Operations Center and the NASA/Air Force Cape Canaveral launch facilities as the John F. Kennedy Space Center.[9]

Johnson was alert to the public demand for answers. To head off snowballing speculation about such conspiracies, he immediately created a panel headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren, known as the Warren Commission, to investigate Kennedy's assassination.[10] The commission conducted extensive research and hearings and unanimously concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassination. Conspiracy theorists were not satisfied and formulated numerous theories which continue to circulate.[11]

Personnel

Johnson retained senior Kennedy appointees, some for the full term of his presidency. Robert Kennedy, brother of the former president, stayed on as Attorney General despite a notoriously difficult relationship between Johnson and the Attorney General. Kennedy remained in office for a few months until leaving in 1964 to successfully run for the Senate.[12] Although Johnson had no official chief of staff, Walter Jenkins was the first among a handful of equals and presided over the details of daily operations at the White House. George Reedy, who was Johnson's second-longest-serving aide, assumed the post of press secretary when John F. Kennedy's own Pierre Salinger left that post in March 1964.[13] Horace Busby was another "triple-threat man," as Johnson referred to his aides. He served primarily as a speech writer and political analyst.[14] Bill Moyers was the youngest member of Johnson's staff. He handled scheduling and speechwriting part-time.[15] Johnson had no vice president during his first term, as the Constitution lacked a mechanism for choosing a replacement vice president until the ratification of the twenty-fifth amendment in 1967. Johnson selected Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota as his running mate for the 1964 election after Humphrey helped pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 through the Senate, and Humphrey served as vice president during Johnson's second term. Johnson created two new Cabinet posts during his presidency: the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and the Secretary of Transportation joined the Cabinet in 1965 and 1966, respectively.

Administration and Cabinet

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

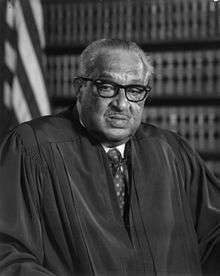

Johnson appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Abe Fortas – 1965

- Thurgood Marshall – 1967

Johnson anticipated court challenges to his legislative measures, and thought it would be advantageous to have a close confidant on the Supreme Court who could provide him with inside information. Johnson chose to appoint Abe Fortas to the Supreme Court in hopes of filling this role, and Johnson created an opening on the court by convincing Associate Justice Arthur Goldberg to become United States Ambassador to the United Nations.[16] In 1967, Johnson successfully nominated Thurgood Marshall to succeed the retiring Tom C. Clark on the Court; Marshall became the first African-American to serve on the Supreme Court. Clark retired from the Supreme Court after Johnson appointed his son, Ramsey Clark, as Attorney General. When Earl Warren announced his retirement in 1968, Johnson nominated Fortas to succeed him as Chief Justice of the United States, and nominated Homer Thornberry to succeed Fortas as Associate Justice. However, Fortas's nomination was defeated by Senators opposed to Fortas's liberal views and close association with President Johnson.[17] President Richard Nixon instead appointed Warren's replacement in 1969.

Other courts

In addition to his Supreme Court appointments, Johnson appointed 40 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 126 judges to the United States district courts. Johnson also had a small number of judicial appointment controversies, with one appellate and three district court nominees not being confirmed by the United States Senate before Johnson's presidency ended.

Domestic policy

Though many liberals had been suspicious of Johnson during his Congressional career, on taking office, Johnson sought to expand the government on a level comparable to the New Deal.[18] Johnson wanted a catchy slogan for the 1964 campaign to describe his proposed domestic agenda. Eric Goldman, who joined the White House in December of that year, thought Johnson's domestic program was best captured in the title of Walter Lippman's book The Good Society. Richard Goodwin tweaked it—to "The Great Society" and incorporated this in detail as part of a speech for Johnson in May 1964 at the University of Michigan. It encompassed movements of urban renewal, modern transportation, clean environment, anti-poverty, healthcare reform, crime control, and educational reform.[19]

Taxation

Despite his previous role as Senate Majority Leader, Johnson had largely been sidelined in the Kennedy administration.[18] Nonetheless, upon taking office, Johnson decided to pursue many of Kennedy's domestic initiatives, which had largely failed to pass Congress.[18] Johnson worked closely with Harry F. Byrd of Virginia to negotiate a reduction in the budget below $100 billion in exchange for what became overwhelming Senate approval of the Revenue Act of 1964, which provided a major tax cut.[20] Congressional approval followed in late-February and facilitated efforts to follow on civil rights.[21] Johnson's Keynesian economic advisers hoped that the bill, which cut the top tax rate from 91% in 1963 to 70% in 1965, would strengthen the economy without causing inflation.[22]

Late into his first term in office, Johnson signed in law the Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968, the second major tax bill. The product of months of negotiations, he reluctantly signed it to pay for the Vietnam War's mounting costs. The bill included a mix of tax increases and spending cuts.[23]

Civil rights

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Though a product of the South and a protege of segregationist Senator Richard Russell, Jr., Johnson had long been personally sympathetic to the Civil Rights movement,[24] and felt that the time had come to pass the first major civil rights bill since the Reconstruction Era.[25] President Kennedy had submitted a civil-rights bill to Congress in June 1963, which was met with strong opposition.[26][27] Kennedy's bill had already been approved by the House Judiciary Committee, but still faced opposition in the House Rules Committee and the Senate.[28] Historian Robert Caro notes that the bill Kennedy had submitted faced the same tactics that prevented the passage of civil rights bills in the past; southern congressmen and senators used congressional procedure to prevent it from coming to a vote.[29] In particular, they held up all of the major bills Kennedy had proposed and that were considered urgent, especially the tax reform bill, in order to force the bill's supporters to pull it.[29] On taking office, Johnson's first move was to pass the Revenue Act of 1964, which removed the leverage of southern Congressmen who had sought to trade support for the bill in exchange for the dropping of the civil rights measure.[20]

The chairman of the House Rules Committee, Howard Smith, was a segregationist who sought to kill the civil rights bill.[20] Johnson decided on a campaign to use a discharge petition to force it onto the House floor, and he and his allies worked to persuade uncommitted Republicans and Democrats to support the petition.[30] Facing a growing threat that they would be bypassed, the House Rules Committee approved the bill and moved it to the floor of the full House, which passed it on February 10, 1964, by a vote of 290–110.[31] Before the bill's passage, Smith proposed an amendment that added protection from gender discrimination to the bill, in a sly attempt to prevent the bill's passage.[32] However, Smith's maneuver backfired, as the House still voted to approve the bill; 152 Democrats and 136 Republicans voted in favor of it, while the majority of the opposition came from 88 Democrats representing states that had seceded during the Civil War.[33]

Johnson convinced Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield to put the House bill directly into consideration by the full Senate, bypassing the Senate Judiciary Committee and its segregationist chairman James Eastland.[34] Since the tax bill had already passed, and bottling up the bill in a committee was no longer an option, the anti-civil-rights senators were left with the filibuster as their only remaining tool. Overcoming the filibuster required the support of over 20 Republicans, who were growing less supportive due to the fact that their party was about to nominate for president a candidate who opposed the bill.[35] Senator Hubert Humphrey and Mansfield led the effort to pass it in the Senate, and one of their major tasks was to convince Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen and other Midwestern conservatives to support it.[20][36] Johnson and the conservative Dirksen reached a compromise in which the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's enforcement powers were weakened, but civil rights groups still supported the bill due to its "end of de jure segregation."[37] After months of debate, the Senate voted for closure in a 71-29 vote, narrowly clearing the 67-vote threshold then required to break filibusters.[38] Though most of the opposition came from southern Democrats, 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater, and five other Republicans also voted against the bill.[38] On June 19, the Senate voted to 73-27 in favor of the bill, sending it to the president.[39]

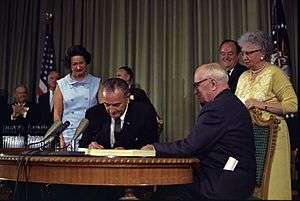

Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law on July 2. Legend has it that as he put down his pen Johnson told an aide, "We have lost the South for a generation", anticipating a coming backlash from Southern whites against Johnson's Democratic Party.[40] The act banned segregation in public accommodations, banned employment gender discrimation, and strengthened the federal government's power to investigate racial and gender employment discrimination.[41] The law later upheld by the Supreme Court in cases such as Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States.[20]

Biographer Randall B. Woods has argued that Johnson effectively used appeals to Judeo-Christian ethics to garner support for the civil rights law. Woods writes that Johnson undermined the Southern filibuster against the bill:

LBJ wrapped white America in a moral straight jacket. How could individuals who fervently, continuously, and overwhelmingly identified themselves with a merciful and just God continue to condone racial discrimination, police brutality, and segregation? Where in the Judeo-Christian ethic was there justification for killing young girls in a church in Alabama, denying an equal education to black children, barring fathers and mothers from competing for jobs that would feed and clothe their families? Was Jim Crow to be America's response to "Godless Communism"? [42]

Voting Rights Act

Johnson began his elected presidential term with similar motives as he had upon succeeding to the office, ready to "carry forward the plans and programs of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Not because of our sorrow or sympathy, but because they are right."[43] He was reticent to push southern congressmen even further after passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and suspected their support may have been temporarily tapped out. Nevertheless, the Selma to Montgomery marches in Alabama led by Martin Luther King ultimately led Johnson to initiate debate on a voting rights bill in February 1965.[44] The 15th Amendment had barred voting discrimination, but African-Americans were still largely denied the right to vote through mechanisms, such as literacy tests and poll taxes.[45]

Johnson gave a congressional speech—Dallek considers it his greatest—in which he said, "rarely at anytime does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself…rarely are we met with the challenge… to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved nation. The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation."[46] In 1965, he achieved passage of the Voting Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination in voting thus allowing millions of southern blacks to vote for the first time. In accordance with the act, several states, "seven of the eleven southern states of the former confederacy" (Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia) were subjected to the procedure of preclearance in 1965 while Texas, home to the majority of the African American population at the time, followed in 1975.[47] The Senate passed the voting rights bill by a vote of 77-19 just after 2 1/2 months and won passage in the house in July, by 333–85. The results were significant—between the years of 1968 and 1980, the number of southern black elected state and federal officeholders nearly doubled. The act also made a large difference in the numbers of black elected officials nationally—in 1965, a few hundred black office-holders mushroomed to 6,000 in 1989.[46] Perhaps most impressively, between 1964 and 1967, the voter registration rate of Mississippi African-Americans rose form 6.7 percent to 59.8 percent.[48]

After the murder of civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo, Johnson went on television to announce the arrest of four Ku Klux Klansmen implicated in her death. He angrily denounced the Klan as a "hooded society of bigots," and warned them to "return to a decent society before it's too late." Johnson was the first President to arrest and prosecute members of the Klan since Ulysses S. Grant about 93 years earlier.[49] He turned to themes of Christian redemption to push for civil rights, thereby mobilizing support from churches North and South.[50] At the Howard University commencement address on June 4, 1965, he said that both the government and the nation needed to help achieve goals, "To shatter forever not only the barriers of law and public practice, but the walls which bound the condition of many by the color of his skin. To dissolve, as best we can, the antique enmities of the heart which diminish the holder, divide the great democracy, and do wrong—great wrong—to the children of God...[51]

1968 Civil Rights Act

Johnson expected to lose seats in the 1966 mid-term elections, and chose to pursue a housing discrimination bill as his final major legislative goal of the 89th Congress.[52] In April 1966, Johnson submitted a bill to Congress that barred owners from refusing to enter into agreements on the basis of race; the bill immediately garnered opposition from many of the northerners who had supported the last two major civil rights bills.[53] Though a version of the bill passed the House, it failed to win Senate approval, marking Johnson's first major legislative defeat.[54] The law gained new impetus after the April 4, 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the civil unrest across the country following King's death.[55] On April 5, Johnson wrote a letter to the United States House of Representatives urging passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.[56] With newly urgent attention from legislative director Joseph Califano and Democratic Speaker of the House John McCormack, the bill passed the House by a wide margin on April 10.[55][57] The Fair Housing Act, a component of the bill, outlawed housing discrimination, and allowed many African-Americans to move to the suburbs.[58]

War on Poverty

After the passage of the Revenue Act of 1964, and while the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was being debated in the Senate, Johnson looked to further bolster his legislative record in advance of the 1964 election.[59] While the previous two bills had been priorities of Kennedy, Johnson chose to next focus on the War on Poverty based on the advice of economist Walter Heller.[60] In April 1964, Johnson proposed the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which would create the Office of Economic Opportunity to oversee local Community Action Agencies charged with dispensing aid to those in poverty.[60] The act would also create the Job Corps, a work-training program, and AmeriCorps VISTA, a domestic version of the Peace Corps.[61] Johnson was able to win the support of enough conservative Democrats to pass the bill, which he signed on August 20.[62] Sargent Shriver, a brother-in-law of John Kennedy, became the first head of the Office of Economic Opportunity.

Johnson took an additional step in the War on Poverty with an urban renewal effort, presenting to Congress in January 1966 the "Demonstration Cities Program". To be eligible a city would need to demonstrate its readiness to "arrest blight and decay and make substantial impact on the development of its entire city." Johnson requested an investment of $400 million per year totaling $2.4 billion. In the fall of 1966 the Congress passed a substantially reduced program costing $900 million, which Johnson later called the Model Cities Program. Changing the name had little effect on the success of the bill; the New York Times wrote 22 years later that the program was for the most part a failure.[63]

Federal funding for education

Johnson, whose own ticket out of poverty was a public education in Texas, fervently believed that education was a cure for ignorance and poverty, and was an essential component of the American dream, especially for minorities who endured poor facilities and tight-fisted budgets from local taxes.[64] In the 1960s, education funding was especially tight due to the demographic challenges posed by the large Baby Boomer generation, but Congress had repeatedly rejected increased federal financing for public schools.[65] Johnson made education the top priority of the Great Society agenda, with an emphasis on helping poor children. After the 1964 landslide brought in many new liberal Congressmen, LBJ launched a legislative effort which took the name of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965. The bill sought to double federal spending on education from $4 billion to $8 billion.;[66] with considerable facilitating by the White House, it passed the House by a vote of 263 to 153 on March 26 and then it remarkably passed without change in the Senate, by 73 to 8, without going through the usual conference committee. This was an historic accomplishment by the president, with the billion dollar bill passing as introduced just 87 days before.[67] For the first time, large amounts of federal money went to public schools. In practice ESEA meant helping all public school districts, with more money going to districts that had large proportions of students from poor families.[68] Johnson was able to pass the bill for a few reasons: the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made segregation in public schools a relative non-issue for the, a "pupil-centered" approach to federal funding neutralized the divisive issue of funding parochial schools, and large Democratic majorities diluted the influence of many Republicans who tended to dislike teacher's unions.[69]

Johnson's second major education program was the Higher Education Act of 1965, which focused on funding for lower income students, including grants, work-study money, and government loans. College graduation rates boomed after the passage of the act, with the percentage of college graduates tripling from 1964 to 2013.[58] Johnson also signed a third important education bill in 1965, establishing the Head Start program to provide grants for preschools.[70]

Johnson created a new role for the federal government in supporting the arts, humanities, and public broadcasting. His administration set up the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, to support humanists and artists (as the WPA once did).[71] In 1967, Johnson signed the Public Broadcasting Act to create educational television programs.[72] The government had set aside radio bands for educational non-profits in the 1950s, and the Federal Communications Commission under President Kennedy had awarded the first federal grants to educational television stations, but Johnson sought to create a vibrant public television that would promote local diversity as well as educational programs.[72] The legislation, which was based on the findings of the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, created a decentralized network of public television stations.[72]

Healthcare reform

Former President Harry Truman had proposed a national health insurance system in 1945, and Johnson was heavily influenced by Truman's ideas.[73] Since 1957, a group of Democrats had advocated for the government to cover the cost of hospital visits for seniors, who had seen higher health costs with the advent of new technologies such as antibiotics, but the American Medical Association and fiscal conservatives opposed a government role in health insurance.[74] Johnson supported the passage of the King-Anderson Bill, which would establish a Medicare program for older patients administered by the Social Security Administration and financed by payroll taxes.[75] Wilbur Mills, chairman of the key House Ways and Means Committee, had long opposed such reforms, but the election of 1964 had defeated many allies of the AMA and shown that the public supported some version of public medical care.[76] Mills suggested that Medicare be fashioned as a three layer cake—hospital insurance under Social Security, a voluntary insurance program for doctor visits, and an expanded medical welfare program for the poor, known as Medicaid.[77] The bill passed the House in April on 313-115 vote, and the Senate passed its a more liberal version of the bill on July 9.[78] After a conference committee session dominated by Mills, the House and Senate passed identical versions of the bill, and Johnson signed the bill on July 30, 1965.[79] Johnson gave the first two Medicare cards to former President Truman and his wife Bess after signing the Medicare bill at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri.[80] Medicare and Medicaid now cover millions of Americans.

Immigration

With the passage of the sweeping Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the country's immigration system was reformed and all national origins quotas dating from the 1920s were removed. The percentage of foreign-born in the United States increased from 5% in 1965 to 14% in 2016.[81] Scholars give Johnson little credit for the law, which was not one of his priorities; he had supported the restrictive McCarren-Walters Act of 1952 that was unpopular with reformers.[82] Regardless, the Immigration and Nationality Act dramatically changed the ethnic composition of the United States, ending the National Origins Formula which had heavily favored European immigrants.[83] The act also prioritized family reunification over the national origins of potential immigrants.[84] Johnson also signed the Cuban Adjustment Act, which granted Cuban refugees an easier path to permanent residency and citizenship.[85]

Transportation

In March 1965, Johnson sent to Congress a transportation message which included the creation of a new Transportation Department—which would include the Commerce Department's Office of Transportation, the Bureau of Public Roads, the Federal Aviation Agency, the Coast Guard, the Maritime Administration, the Civil Aeronautics Board and the Interstate Commerce Commission. The bill passed the Senate after some negotiation over navigation projects; in the house, passage required negotiation over maritime interests and the bill was signed October 15, 1965.[86]

Gun control

Following the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr., Johnson signed two major gun control laws. In addition to the assassinations, Johnson's push for gun control was also motivated by mass shootings such as the one perpetrated by Charles Whitman.[87] Johnson signed the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 shortly after Robert Kennedy's death. On October 22, 1968, Lyndon Johnson signed the Gun Control Act of 1968, one of the largest and farthest-reaching federal gun control laws in American history. The measure prohibited convicted felons, drug users, and the mentally ill from purchasing handguns and raised record-keeping and licensing requirements.[88] Johnson had sought to require the licensing of gun owners and the registration of all firearms, but could not convince Congress to pass a stronger bill.[89]

Space program

During Johnson's administration, NASA conducted the Gemini manned space program, developed the Saturn V rocket and its launch facility, and prepared to make the first manned Apollo program flights. On January 27, 1967, the nation was stunned when the entire crew of Apollo 1 was killed in a cabin fire during a spacecraft test on the launch pad, stopping Apollo in its tracks. Rather than appointing another Warren-style commission, Johnson accepted Administrator James E. Webb's request for NASA to do its own investigation, holding itself accountable to Congress and the President.[90] Johnson maintained his staunch support of Apollo through Congressional and press controversy, and the program recovered. The first two manned missions, Apollo 7 and the first manned flight to the Moon, Apollo 8, were completed by the end of Johnson's term. He congratulated the Apollo 8 crew, saying, "You've taken ... all of us, all over the world, into a new era."[91][92] Less than a year after leaving office, Johnson attended the launch of Apollo 11, the first Moon landing mission.

Urban riots

Major riots in black neighborhoods caused a series of "long hot summers." They started with a violent disturbance in the Harlem riots in 1964, and the Watts district of Los Angeles in 1965, and extended to 1971. The momentum for the advancement of civil rights came to a sudden halt in the summer of 1965, with the riots in Watts. After 34 people were killed and $35 million in property was damaged, the public feared an expansion of the violence to other cities, and so the appetite for additional programs in LBJ's agenda was lost.[93] Riots in 1967 in particular began to turn much of the public against the War on Poverty, which became associated with urban policy despite much of its funding being devoted to rural areas.[94]

The biggest wave of riots came in April 1968 in over a hundred cities after the assassination of Martin Luther King. Newark burned in 1967, where six days of rioting left 26 dead, 1500 injured, and the inner city a burned out shell. In Detroit in 1967, Governor George Romney sent in 7400 national guard troops to quell fire bombings, looting, and attacks on businesses and on police. Johnson finally sent in federal troops with tanks and machine guns. Detroit continued to burn for three more days until finally 43 were dead, 2250 were injured, 4000 were arrested; property damage ranged into the hundreds of millions. Johnson called for even more billions to be spent in the cities and another federal civil rights law regarding housing, but this fell on deaf ears. Johnson's popularity plummeted as a massive white political backlash took shape, reinforcing the sense Johnson had lost control of the streets of major cities as well as his party.[95] Johnson created the Kerner Commission to study the problem of urban riots, headed by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner. According to press secretary George Christian, Johnson was unsurprised by the riots, saying: "What did you expect? I don't know why we're so surprised. When you put your foot on a man's neck and hold him down for three hundred years, and then you let him up, what's he going to do? He's going to knock your block off."[96]

Foreign policy

Vietnam

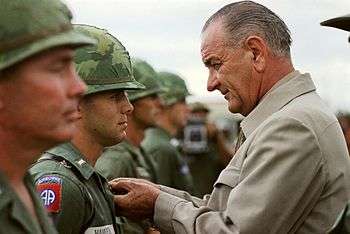

The Indochina Wars had been raging since the Japanese invasion of French Indochina during World War II, and France struggled to re-establish control over its former colonies after World War II. The Communist Viet Minh successively opposed Japanese and French forces in Vietnam, and established a Communist North Vietnam following the 1954 Geneva Agreements. The Vietnam War began in 1955 as North Vietnamese forces, with the support of the Soviet Union, China, and other Communist governments, sought to reunify the country by taking control of South Vietnam. On taking office, Johnson made clear that he was not planning any major changes regarding the American role in Vietnam.[97] At Kennedy's death, there were already 16,000 American military personnel in Vietnam, supporting the nominally democratic South Vietnamese government.[98] However, Johnson's presidency ultimately saw a massive build-up of the American presence in Vietnam, with troop levels reaching a peak above 500,000 by the end of Johnson's tenure.[99] Johnson subscribed to the Domino Theory, which speculated that the fall of one government to Communism would lead to the fall of surrounding governments. Johnson thus adhered to the containment policy that required America to make a serious effort to stop all Communist expansion.[100] Johnson also feared that the fall of Vietnam would hurt Democratic credibility on national security issues and undermine Johnson's domestic initiatives, much as the "Loss of China" and the Korean War hurt Democrats in the 1950s.[101][102] As American involvement in the war dragged on, the war became increasingly unpopular and a large anti-war movement arose. The Vietnam War would continue until 1975, well past the end of Johnson's time in office.

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

In August 1964, allegations arose from the military that two US destroyers had been attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats in international waters 40 miles (64 km) from the Vietnamese coast in the Gulf of Tonkin; naval communications and reports of the attack were contradictory. Although Johnson very much wanted to keep discussions about Vietnam out of the 1964 election campaign, he felt forced to respond to the supposed aggression by the Vietnamese, so he sought and obtained from the Congress the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on August 7. Johnson, determined to embolden his image on foreign policy, also wanted to prevent criticism such as Truman had received in Korea by proceeding without congressional endorsement of military action; a response to the purported attack as well blunted presidential campaign criticism of weakness from the hawkish Goldwater camp. The resolution gave congressional approval for use of military force by the commander-in-chief to repel future attacks and also to assist members of SEATO requesting assistance. Johnson later in the campaign expressed assurance that the primary US goal remained the preservation of South Vietnamese independence through material and advice, as opposed to any US offensive posture.[103] The public's reaction to the resolution at the time was positive—48 percent favored stronger measures in Vietnam and only 14 percent wanted to negotiate a settlement and leave.[104]

1964

Johnson in late summer 1964 seriously questioned the value of staying in Vietnam but, after meeting with Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Maxwell D. Taylor, declared his readiness "to do more when we had a base" or when Saigon was politically more stable.[105] In the 1964 presidential campaign, he restated his determination to provide measured support for Vietnam while avoiding another Korea; but privately he had a sense of foreboding about Vietnam—a feeling that no matter what he did things would end badly. Indeed, his heart was on his Great Society agenda, and he even felt that his political opponents favored greater intervention in Vietnam in order to divert attention and resources away from his War on Poverty. The situation on the ground was aggravated in the fall by additional Viet Minh attacks on US ships in the Tonkin Gulf, as well as an attack on Bien Hoa airbase in South Vietnam.[106] Johnson decided against retaliatory action at the time after consultation with the Joint Chiefs and also after public pollster Lou Harris confirmed that his decision would not detrimentally affect him at the polls.[107] By the end of 1964, there were approximately 23,000 military personnel in South Vietnam. U.S. casualties for 1964 totaled 1,278.[98]

In the winter of 1964–65 Johnson was pressured by the military to begin a bombing campaign to forcefully resist a communist takeover in South Vietnam; moreover, a plurality in the polls at the time were in favor of military action against the communists, with only 26 to 30 percent opposed.[108] Johnson revised his priorities, and a new preference for stronger action came at the end of January with yet another change of government in Saigon. He then agreed with Mac Bundy and McNamara, that the continued passive role would only lead to defeat and withdrawal in humiliation. Johnson said, "Stable government or no stable government in Saigon we will do what we ought to do. I'm prepared to do that; we will move strongly. General Nguyễn Khánh (head of the new government) is our boy".[109]

1965

Johnson decided on a systematic bombing campaign in February after a ground report from Bundy recommending immediate US action to avoid defeat; also, the Viet Cong had just killed eight US advisers and wounded dozens of others in an attack at Pleiku Air Base. The eight-week bombing campaign became known as Operation Rolling Thunder. Johnson's instructions for public consumption were clear—there was to be no comment that the war effort had been expanded.[110] Long term estimates of the bombing campaign ranged from an expectation that Hanoi would rein in the Viet Cong to one of provoking Hanoi and the Viet Cong into an intensification of the war. But the short-term expectations were consistent - that the morale and stability of the South Vietnamese government would be bolstered. By limiting the information given out to the public and even to Congress, Johnson maximized his flexibility to change course.[111]

In March, Bundy began to urge the use of ground forces—American air operations alone he counseled would not stop Hanoi's aggression against the South. Johnson approved an increase in logistical troops of 18,000 to 20,000, the deployment of two additional Marine battalions and a Marine air squadron, in addition to planning for the deployment of two more divisions—and most importantly a change in mission from defensive to offensive operations; nevertheless, he disobligingly continued to insist that this was not to be publicly represented as a change in existing policy.[112]

After a conference of advisors in Honolulu in April 1965, by the middle of June the total US ground forces in Vietnam were increased to 82,000 or by 150 percent.[113] On May 2, 1965 Johnson told congressional leaders that he wanted an additional $700 million for Vietnam and the Dominican Republic saying "each member of Congress who supports this request is voting to continue our effort to try to hold communist aggression". The request was approved by the House 408 to 7 and by the Senate 88 to 3.[114] In June Ambassador Taylor reported that the bombing offensive against North Vietnam had been ineffective, and that the South Vietnamese army was outclassed and in danger of collapse.[115] Gen. Westmoreland shortly thereafter recommended the president further increase ground troops from 82,000 to 175,000. After consulting with his principals, Johnson, desirous of a low profile, chose to announce at a press conference an increase to 125,000 troops, with additional forces to be sent later upon request. In order to mute his announcement, Johnson at the same time announced the nomination of Abe Fortas to the Supreme Court and John Chancellor as director of the Voice of America. Johnson described himself at the time as boxed in by unpalatable choices—between sending Americans to die in Vietnam and giving in to the communists. If he sent additional troops he would be attacked as an interventionist and if he did not he thought he risked being impeached. He continued to insist that his decision "did not imply any change in policy whatsoever". Of his desire to veil the decision, Johnson jested privately, "If you have a mother-in-law with only one eye, and she has it in the center of her forehead, you don't keep her in the living room".[116] By October 1965 there were over 200,000 troops deployed in Vietnam.[117]

Polls showed that beginning in 1965, the public was consistently 40–50 percent hawkish and 10–25 percent dovish. Johnson's aides told him, "Both hawks and doves [are frustrated with the war] ... and take it out on you."[118] Politically, Johnson closely watched the public opinion polls. His goal was not to adjust his policies to follow opinion, but rather to adjust opinion to support his policies. Until the Tet Offensive of 1968, he systematically downplayed the war; he made very few speeches about Vietnam, and held no rallies or parades or advertising campaigns. He feared that publicity would charge up the hawks who wanted victory, and weaken both his containment policy and his higher priorities in domestic issues. Jacobs and Shapiro conclude, "Although Johnson held a core of support for his position, the president was unable to move Americans who held hawkish and dovish positions."

On April 2, 1965, the current Canadian Prime Minister, Lester B. Pearson, gave a speech at Temple University in Philadelphia. During his speech, he voiced his support for a pause in the American bombing of North Vietnam, so that a diplomatic solution to the crisis may unfold. To President Johnson, this criticism of American foreign policy on American soil was an intolerable sin. Before Pearson had finished his speech, he was summoned to Camp David, Maryland, to meet with Johnson the next day. Johnson, who was notorious for his personal touch in politics, reportedly grabbed Pearson by the lapels and shouted, "Don't you come into my living room and piss on my rug."[119][120]

1966

At the end of 1965 after consultation with the Joint Chiefs and other advisers Johnson decided to increase troops at the rate of 15,000 per month throughout 1966 rather than increasing them at one time, in order to avoid a more publicized increase. At the same time there was deliberation over a bombing pause and Johnson finally agreed on December 28 to a pause and a corresponding "peace offensive"; the pause in bombing and the peace blitz ended January 31 without discernible effect. Disturbed by criticism of the war, then underscored with public hearings by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in January, Johnson convened a second Honolulu conference, and personally attended for three days along with Ambassador Lodge, Gen. Westmoreland, the Vietnamese Chief of State Nguyen Van Thieu and Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky.[121] In April 1966 Johnson was encouraged by statistics that the Viet Cong had suffered greater numbers of casualties than the South Vietnamese; at the same time, despite urgings in Honolulu to strengthen his internal affairs, Prime Minister Ky's administration was increasingly vulnerable to rebel forces. The administration pressured Ky to hasten a transfer of power to an assembly but he demurred.[122]

Public as well as political impatience with the war began to emerge in the spring of 1966. At the time, when Johnson's approval ratings were reaching new lows of 41 percent, Sen. Richard Russell, Chairman of the Armed Services Committee, reflected the national mood in June 1966, when he declared it was time to "get it over or get out".[123] Johnson responded by saying to the press, "we are trying to provide the maximum deterrence that we can to communist aggression with a minimum of cost."[124] In response to the intensified criticism of the war effort, Johnson employed the suspicion of communist subversion in the country, and press relations became strained.[125] Johnson's primary war policy opponent in Congress included among others the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, James William Fulbright.[126] The persistent Johnson began to seriously consider a more focused bombing campaign against petroleum, oil and lubrication facilities in North Vietnam in hopes of accelerating victory.[127] Humphrey, Rusk and McNamara all agreed; the bombing began the end of June.[128] In July polling results indicated that Americans favored the bombing campaign by a 5 to 1 margin; however, in August a Defense Department study indicated that the bombing campaign had little impact on North Vietnam.[129]

In the fall of 1966 however, multiple sources began to report progress was being made against the North Vietnamese logistics and infrastructure; Johnson was urged from every corner to begin peace discussions. There was no shortage of peace initiatives; nevertheless, among protesters, English philosopher Bertrand Russell attacked Johnson's policy as "a barbaric aggressive war of conquest" and in June he initiated the International War Crimes Tribunal as a means to condemn the American effort.[130] The gap with Hanoi was an unbridgeable demand on both sides for a unilateral end to bombing and withdrawal of forces. In August, Johnson appointed Averell Harriman "Ambassador for Peace" to promote negotiations. Westmoreland and McNamara then recommended a concerted program to promote pacification; Johnson formally placed this effort under military control in October.[131]

In October 1966, Johnson travelled abroad to reassure allies and promote his war effort. He visited New Zealand, and Australia, where he was greeted by demonstrations from anti-war protesters,[132] while on his way to Manila for summit conference with the heads of State and government of Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Korea, South Vietnam, and Thailand.[133] The conference ended with pronouncements to stand fast against communist aggression and to promote ideals of democracy and development in Vietnam and across Asia.[134] For Johnson it was a fleeting public relations success—confirmed by a 63 percent Vietnam approval rating in November.[135] Nevertheless, in December Johnson's Vietnam approval rating was again back down in the 40s; LBJ had become anxious to justify war casualties, and talked of the need for decisive victory, despite the unpopularity of the cause.[136] In a discussion about the war with former President Dwight Eisenhower on October 3, 1966, Johnson said he was "trying to win it just as fast as I can in every way that I know how" and later stated that he needed "all the help I can get."[137]

By year's end it was clear that current pacification efforts were ineffectual, as had been the air campaign. Johnson then agreed to McNamara's new recommendation to add 70,000 troops in 1967 to the 400,000 previously committed. While McNamara recommended no increase in the level of bombing, Johnson agreed with CIA recommendations to increase them.[138] The increased bombing began despite initial secret talks being held in Saigon, Hanoi and Warsaw. While the bombing ended the talks, North Vietnamese intentions were not considered genuine.[139]

1967

January and February 1967 included probes to detect North Vietnamese willingness to discuss peace, and all fell on deaf ears. Ho Chi Minh declared that the only solution was a unilateral withdrawal by the U.S.[140] Corrected military estimates released in March indicated a greater number of enemy-initiated actions between February 1966 and 1967; this exemplified the unreliability of information coming from the ground in Vietnam; similar discrepancies existed in measuring the movement of supplies and forces from North to South and assessing Viet Cong manpower. In February Johnson nevertheless agreed to attacks on infiltration routes in Laos and fifty-four new targets in the North, as well as the mining of inland waterways to complement bombing.[141]

In March Robert Kennedy assumed a more public opposition to the war in a Senate speech. The fact of his opposition and probable candidacy for the presidency in 1968, according to Dallek, inhibited the embattled and embittered Johnson from employing a more realistic war policy.[142] Johnson's anger and frustration over the lack of a solution to Vietnam and its effect on him politically was exhibited in a statement to Kennedy. Johnson had just received several reports predicting military progress by the summer, and warned Kennedy, "I'll destroy you and every one of your dove friends in six months", he shouted. "You'll be dead politically in six months".[143] In June a decisive 66% of the country said they had lost confidence in the President's leadership.[144] McNamara actually offered Johnson a way out of Vietnam in May; the administration could declare its objective in the war—South Vietnam's self-determination—was being achieved and upcoming September elections in South Vietnam would provide the chance for a coalition government. The United States could reasonably expect that country to then assume responsibility for the election outcome. But Johnson was reluctant, in light of some optimistic reports, again of questionable reliability, which matched the negative assessments about the conflict and provided hope of improvement. The CIA was reporting wide food shortages in Hanoi and an unstable power grid, as well as military manpower reductions.[145]

By the middle of 1967 nearly 70,000 Americans had been killed or wounded in the war. In July, Johnson sent McNamara, Wheeler and other officials to meet with Westmoreland and reach agreement on plans for the immediate future. At that time the war was being commonly described by the press and others as a "stalemate". Westmoreland said such a description was pure fiction, and that "we are winning slowly but steadily and the pace can excel if we reinforce our successes".[146] Though Westmoreland sought many more, Johnson agreed to an increase of 55,000 troops bringing the total to 525,000.[99] A Gallup poll in July showed 52 percent of the country disapproving of the president's handling of the war and only 34 percent thought progress was being made.[147]

In August Johnson, with the Joint Chiefs' support, decided to expand the air campaign and exempted only Hanoi, Haiphong and a buffer zone with China from the target list.[148] Later that month McNamara told a Senate subcommittee that an expanded air campaign would not bring Hanoi to the peace table—the Joint Chiefs were astounded, and threatened mass resignation—McNamara was summoned to the White House for a three-hour dressing down; nevertheless, Johnson had received reports from the CIA confirming McNamara's analysis at least in part. In the meantime an election establishing a constitutional government in the South was concluded and provided hope for peace talks.[149]

Despite the election, the South Vietnam government remained incompetent and riddled with corruption; but, in September Ho Chi Minh and North Vietnamese premier Pham Van Dong appeared amenable to French mediation, so Johnson ceased bombing in a 10-mile zone around Hanoi; this was met with dissatisfaction. Johnson in a Texas speech agreed to halt all bombing if Ho Chi Minh would launch productive and meaningful discussions and if North Vietnam would not seek to take advantage of the halt; this was named the "San Antonio" formula. There was no response, but Johnson pursued the possibility of negotiations with such a bombing pause.[150]

Fellow Democrat Tip O'Neill joined the ranks of those opposed to the war in late 1967. And with the ever increasing public protests against the war, in October Johnson engaged the FBI and the CIA to investigate, monitor and undermine antiwar activists.[151] In mid-October there was a demonstration of 100,000 at the Pentagon; Johnson and Rusk were convinced that foreign communist sources were behind the demonstration, which was refuted by CIA findings.[152]

With the war still arguably in a stalemate and in light of the widespread disapproval of the conflict, Johnson convened a group called the "Wise Men" for a fresh, in-depth look at the war—Dean Acheson, Gen. Omar Bradley, George Ball, Mac Bundy, Arthur Dean, Douglas Dillon, Abe Fortas, Averell Harriman, Henry Cabot Lodge, Robert Murphy and Max Taylor.[153] At that time McNamara, reversing his position on the war, recommended that a cap of 525,000 be placed on the number of forces deployed and that the bombing be halted, since he could see no success. Johnson was quite agitated by this recommendation and described McNamara as "ready to pull another Forrestal"– a reference to the suicide of former Defense Secretary James Forrestal. McNamara's resignation soon followed.[154] With the exception of George Ball, the "Wise Men" all agreed the administration should "press forward".[155] Johnson was confident that Hanoi would await the 1968 US election results before deciding to negotiate.[156]

1968

As casualties mounted and success seemed further away than ever, Johnson's popularity plummeted. College students and others protested, burned draft cards, and chanted, "Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?"[100] Johnson could scarcely travel anywhere without facing protests, and was not allowed by the Secret Service to attend the 1968 Democratic National Convention, where thousands of hippies, yippies, Black Panthers and other opponents of Johnson's policies both in Vietnam and in the ghettos converged to protest.[157] Thus by 1968, the public was polarized, with the "hawks" rejecting Johnson's refusal to continue the war indefinitely, and the "doves" rejecting his current war policies. Support for Johnson's middle position continued to shrink until he finally rejected containment and sought a peace settlement. By late summer, he realized that Nixon was closer to his position than Humphrey. He continued to support Humphrey publicly in the election, and personally despised Nixon. One of Johnson's well known quotes was "the Democratic party at its worst, is still better than the Republican party at its best".[158]

On January 30 came the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Tet offensive against South Vietnam's five largest cities, including Saigon and the US embassy there and other government installations. While the Tet offensive failed militarily, it was a psychological victory, definitively turning American public opinion against the war effort. Iconically, Walter Cronkite of CBS news, voted the nation's "most trusted person" in February expressed on the air that the conflict was deadlocked and that additional fighting would change nothing. Johnson reacted, saying "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost middle America".[159] Indeed, demoralization about the war was everywhere; 26% then approved of Johnson's handling of Vietnam; 63% disapproved. Johnson agreed to increase the troop level by 22,000, despite a recommendation from the Joint Chiefs for ten times that number,[160] By March 1968 Johnson was secretly desperate for an honorable way out of the war. Clark Clifford, the new Defense Secretary, described the war as "a loser" and proposed to "cut losses and get out".[161] On March 31 Johnson spoke to the nation of "Steps to Limit the War in Vietnam". He then announced an immediate unilateral halt to the bombing of North Vietnam and announced his intention to seek out peace talks anywhere at any time. At the close of his speech he also announced, "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President".[162]

In March Johnson decided to restrict future bombing with the result that 90 percent of North Vietnam's population and 75 percent of its territory was off-limits to bombing. In April he succeeded in opening discussions of peace talks and after extensive negotiations over the site, Paris was agreed to and talks began in May. When the talks failed to yield any results the decision was made to resort to private discussions in Paris.[163] Two months later it was apparent that private discussions proved to be no more productive.[164] Despite recommendations in August from Harriman, Vance, Clifford and Bundy to halt bombing as an incentive for Hanoi to seriously engage in substantive peace talks, Johnson refused.[165] In October when the parties came close to an agreement on a bombing halt, Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon intervened with the South Vietnamese, and made promises of better terms, so as to delay a settlement on the issue until after the election.[166] After the election, Johnson's primary focus on Vietnam was to get Saigon to join the Paris peace talks. Ironically, only after Nixon added his urging did they do so. Even then they argued about procedural matters until after Nixon took office.[167]

A few analysts have theorized that "Vietnam had no independent impact on President Johnson's popularity at all after other effects, including a general overall downward trend in popularity, had been taken into account."[168] The war grew less popular, and continued to split the Democratic Party. The Republican Party was not completely pro- or anti-war, and Nixon managed to get support from both groups by running on a reduction in troop levels with an eye toward eventually ending the campaign.

Johnson often privately cursed the Vietnam War and, in a conversation with Robert McNamara, he assailed "the bunch of commies" running The New York Times for their articles against the war effort.[169] Johnson once summed up his perspective of the Vietnam War as follows:

I knew from the start that I was bound to be crucified either way I moved. If I left the woman I really loved—the Great Society—in order to get involved in that bitch of a war on the other side of the world, then I would lose everything at home. All my programs.... But if I left that war and let the Communists take over South Vietnam, then I would be seen as a coward and my nation would be seen as an appeaser and we would both find it impossible to accomplish anything for anybody anywhere on the entire globe.[170]

Soviet Union

Though committed to containment, Johnson pursued a non-confrontational policy with the Soviet Union itself, setting the stage for the détente of the 1970s.[171][172] Johnson was extremely concerned with averting the possibility of nuclear war, and sought to reduce tensions in Europe.[173] The Johnson administration pursued arms control agreements with the Soviet Union, signing the Outer Space Treaty and the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, and laid the foundation for the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks.[171] Johnson held a largely amicable meeting with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin at the Glassboro Summit Conference in 1967. The next year, Warsaw Pact forces crushed the Prague Spring, an attempted democratization of Czechoslovakia. The military intervention ended Johnson's hopes of an arms control summit, though the United States never seriously considered directly intervening on behalf of Czechoslovakia.[174]

The Six-Day War and Israel

In June 1967, tensions between Israel and neighboring Arab states escalated into a war that became known as the Six-Day War. The Soviet Union considered a naval invasion of Israel to protect its Arab allies, and demanded that the United States ask Israel to end the war.[175] While Johnson did not publicly support Israel's war efforts, he refused to intervene as President Dwight Eisenhower had in the Suez Crisis.[176] The crisis saw the first activation of the Moscow-Washington hotline that had been established in 1963.[175] Ultimately, no war broke among the great powers, and the Israelis quickly won the Six-Day War, capturing the Sinai Peninsula and other neighboring territories.

Intervention in the Dominican Republic

In early 1965 Johnson sent U.S. Marines to the Dominican Republic to protect the embassy there and to respond to yet another perceived communist threat by the escalating civil war. That spring an agreement was reached at the urging of the OAS and the US to end the uprising; this crisis reinforced Johnson's belief it was essential to convince supporters and opponents at home and abroad that he had an effective strategy to meet the communist challenge in Vietnam.[177]

List of international trips

Johnson made eleven international trips to twenty countries during his presidency.[178] He flew 523,000 miles aboard Air Force One while in office. One of the most unusual international trips in presidential history occurred before Christmas in 1967. The President began the trip by going to the memorial service for Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt, who had disappeared in a swimming accident and was presumed drowned. The White House did not reveal in advance to the press that the President would make the first round-the-world presidential trip. The trip was 26,959 miles completed in only 112.5 hours (4.7 days). Air Force One crossed the equator twice, stopped in Travis Air Force Base, Calif., then Honolulu, Pago Pago, Canberra, Melbourne, Vietnam, Karachi and Rome.

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | September 16, 1964 | Vancouver | Informal visit. Met with Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson in ceremonies related to the Columbia River Treaty. | |

| 2 | April 14–15, 1966 | Mexico, D.F. | Informal visit. Met with President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. | |

| 3 | August 21–22, 1966 | Campobello Island, Chamcook |

Laid cornerstone at Roosevelt Campobello International Park. Conferred informally with Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson. | |

| 4 | October 19–20, 1966 | Wellington | State visit. Met with Prime Minister Keith Holyoake. | |

| October 20–23, 1966 | Canberra, Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Townsville |

State visit. Met with Governor-General Richard Casey and Prime Minister Harold Holt. | ||

| October 24–26, 1966 | Manila, Los Baños, Corregidor |

Attended the summit conference with the heads of State and government of Australia, Korea, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. | ||

| October 26, 1966 | Cam Ranh Bay | Visited U.S. military personnel. | ||

| October 27–30, 1966 | Bangkok | State visit. Met with King Bhumibol Adulyadej. | ||

| October 30–31, 1966 | Kuala Lumpur | State visit. Met with Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman | ||

| October 31 – November 2, 1966 |

Seoul, Suwon |

State visit. Met with President Park Chung-hee and Prime Minister Chung Il-kwon. Addressed National Assembly. | ||

| 5 | December 3, 1966 | Ciudad Acuña | Informal meeting with President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. Inspected construction of Amistad Dam. | |

| 6 | April 11–14, 1967 | Punta del Este | Summit meeting with Latin American heads of state. | |

| April 14, 1967 | Paramaribo | Refueling stop en route from Uruguay. | ||

| 7 | April 23–26, 1967 | Bonn | Attended the funeral of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and conversed with various heads of state. | |

| 8 | May 25, 1967 | Montreal, Ottawa |

Met with Governor General Roland Michener. Attended Expo 67. Conferred informally with Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson. | |

| 9 | October 28, 1967 | Ciudad Juarez | Attended transfer of El Chamizal from the U.S. to Mexico. Conferred with President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. | |

| 10 | December 21–22, 1967 | Canberra | Attended the funeral of Prime Minister Harold Holt. Conferred with other attending heads of state. | |

| December 23, 1967 | Khorat | Visited U.S. military personnel. | ||

| December 23, 1967 | Cam Ranh Bay | Visited U.S. military personnel. | ||

| December 23, 1967 | Karachi | Met with President Ayub Khan. | ||

| December 23, 1967 | Rome | Met with President Giuseppe Saragat and Prime Minister Aldo Moro. | ||

| December 23, 1967 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with Pope Paul VI. | ||

| 11 | July 6–8, 1968 | San Salvador | Attended the Conference of Presidents of the Central American Republics. | |

| July 8, 1968 | Managua | Informal visit. Met with President Anastasio Somoza Debayle. | ||

| July 8, 1968 | San José | Informal visit. Met with President José Joaquín Trejos Fernández. | ||

| July 8, 1968 | San Pedro Sula | Informal visit. Met with President Oswaldo López Arellano. | ||

| July 8, 1968 | Guatemala City | Informal visit. Met with President Julio César Méndez Montenegro. |

Elections

1964 presidential election

Johnson and his Republican opponent, Barry Goldwater, both sought to portray the election as a choice between a liberal and a conservative, and Goldwater was perhaps the most conservative major party nominee since the passage of the New Deal.[179] The 1964 Democratic National Convention easily re-nominated Johnson and celebrated his accomplishments after less than one year in office.[180] Early in the campaign, Robert F. Kennedy was a widely popular choice to run as Johnson's vice presidential running mate, but Johnson and Kennedy had never liked one another.[181] Johnson, afraid that Kennedy would be credited with his election as president, abhorred the idea and opposed it at every turn.[181] Hubert Humphrey was ultimately selected as Johnson's running mate, with the hope that Humphrey would strengthen the ticket in the Midwest and industrial Northeast.[182] Johnson, knowing full well the degree of frustration inherent in the office of vice president, put Humphrey through a gauntlet of interviews to guarantee his absolute loyalty and having made the decision, he kept the announcement from the press until the last moment to maximize media speculation and coverage.[183] At the end of the convention, polls showed Johnson in a comfortable position to obtain re-election.[184]

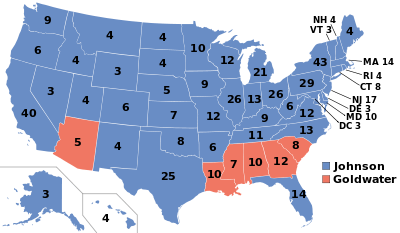

Early in the 1964 presidential campaign, Barry Goldwater had appeared to be a strong contender, with strong support from the South, which threatened Johnson's position as he had predicted in reaction to the passage of the Civil Rights Act. However, Goldwater lost momentum as his campaign progressed. On September 7, 1964, Johnson's campaign managers broadcast the "Daisy ad," which successfully portrayed Goldwater as a dangerous warmonger.[185] The combination of an effective aid campaign, Goldwater's perceived extremism, a poorly-organized Goldwater campaign, and Johnson's popularity led Democrats to a major election victory.[186] Johnson won the presidency by a landslide with 61.05 percent of the vote, making it the highest ever share of the popular vote.[187] At the time, this was also the widest popular margin in the 20th century—more than 15.95 million votes—this was later surpassed by incumbent President Nixon's victory in 1972.[188] In the Electoral College, Johnson defeated Goldwater by margin of 486 to 52. Voters also gave Johnson the largest majorities in Congress since FDR's election in 1936—a Senate with a 68-32 majority and a house with a 295–140 Democratic margin.[189] The huge election victory emboldened Johnson to propose liberal legislation in the 89th United States Congress.[190]

1966 mid-term elections

| Senate leaders | House leaders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Majority | Minority | Speaker | Minority |

| 1963-1964 | Mansfield | Dirksen | McCormack | Halleck |

| 1965-1968 | Mansfield | Dirksen | McCormack | Ford |

In the 1966 elections, Democrats lost nearly 50 seats in the House, but retained a majority in both houses of Congress. Republicans campaigned on law and order concerns stemming from urban riots, hawkish attacks on Johnson's conduct of the Vietnam War, and warnings of the threat of inflation and federal deficits.[191] The elections weakened the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, decreasing Johnson's ability to push his agenda through Congress.[192] The elections also helped the Republicans rehabilitate their image after their disastrous 1964 campaign.[193] Johnson's Democrats were weakened by the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War, urban riots, and a declining economy.[193]

1968 presidential election

| Congress | Senate | House |

|---|---|---|

| 87th | 67 | 258 |

| 88th | 68 | 295 |

| 89th | 64 | 248 |

As he had served less than 24 months of President Kennedy's term, Johnson was constitutionally permitted to run for a second full term in the 1968 presidential election under the provisions of the 22nd Amendment.[194][195] However, beginning in 1966, the press sensed a "credibility gap" between what Johnson was saying in press conferences and what was happening on the ground in Vietnam, which led to much less favorable coverage.[196] By year's end, the Democratic governor of Missouri, Warren E. Hearnes, warned that Johnson would lose the state by 100,000 votes, despite winning by a 500,000 margin in 1964. "Frustration over Vietnam; too much federal spending and... taxation; no great public support for your Great Society programs; and ... public disenchantment with the civil rights programs" had eroded the President's standing, the governor reported. There were bright spots; in January 1967, Johnson boasted that wages were the highest in history, unemployment was at a 13-year low, and corporate profits and farm incomes were greater than ever; a 4.5 percent jump in consumer prices was worrisome, as was the rise in interest rates. Johnson asked for a temporary 6 percent surcharge in income taxes to cover the mounting deficit caused by increased spending. Johnson's approval ratings stayed below 50 percent; by January 1967, the number of his strong supporters had plunged to 16%, from 25 percent four months before. He ran about even with Republican George Romney in trial matchups that spring. Asked to explain why he was unpopular, Johnson responded, "I am a dominating personality, and when I get things done I don't always please all the people." Johnson also blamed the press, saying they showed "complete irresponsibility and lie and misstate facts and have no one to be answerable to." He also blamed "the preachers, liberals and professors" who had turned against him.[197]

As the 1968 election approached, Johnson began to lose control of the Democratic Party, which was splitting into four factions. The first faction consisted of Johnson and Humphrey, labor unions, and local party bosses (led by Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley). The second group consisted of students and intellectuals who were vociferously against the war and rallied behind Eugene McCarthy, who entered the 1968 Democratic primaries came in a surprisingly close second at the March 12 New Hampshire primary. The third group were Catholics, Hispanics and African Americans, who rallied behind Robert Kennedy. Kennedy entered the race shortly after the New Hampshire primary. The fourth group were traditionally segregationist white Southerners, who rallied behind George C. Wallace and the American Independent Party. Johnson could see no way to win the war[100] and no way to unite the party long enough for him to win re-election.[198] At the end of a March 31 speech, Johnson shocked the nation when he announced he would not run for re-election by concluding with the line: "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President."[199] The next day, his approval ratings increased from 36% to 49%.[200] Humphrey entered the race after Johnson's withdrawal.

Historians have debated the factors that led to Johnson's surprise decision. Shesol says Johnson wanted out of the White House but also wanted vindication; when the indicators turned negative he decided to leave.[201] Gould says that Johnson had neglected the party, was hurting it by his Vietnam policies, and underestimated McCarthy's strength until the very last minute, when it was too late for Johnson to recover.[202] Woods said Johnson realized he needed to leave in order for the nation to heal.[203] Dallek says that Johnson had no further domestic goals, and realized that his personality had eroded his popularity. His health was not good, and he was preoccupied with the Kennedy campaign; his wife was pressing for his retirement and his base of support continued to shrink. Leaving the race would allow him to pose as a peacemaker.[204] Bennett, however, says Johnson "had been forced out of a reelection race in 1968 by outrage over his policy in Southeast Asia."[205] Johnson may have hoped that the convention would ultimately choose to draft him back into the race.[206]

After Robert Kennedy's assassination in June, Humphrey won the Democratic nomination with Johnson's backing at the tumultuous 1968 Democratic National Convention.[207] Personal correspondences between the President and some in the Republican Party suggested Johnson tacitly supported Nelson Rockefeller's campaign, but Richard Nixon won the Republican nomination.[208] After the convention, polls showed Humphrey losing by 20 points to Nixon.[207] Humphrey's polling numbers improved after a September 30 speech in which he broke with Johnson's war policy, calling for an end to the bombing of North Vietnam.[207] In what was termed the October surprise, Johnson announced to the nation on October 31, 1968, that he had ordered a complete cessation of "all air, naval and artillery bombardment of North Vietnam", effective November 1, should the Hanoi Government be willing to negotiate and citing progress with the Paris peace talks. However, Nixon won the election, narrowly edging Humphrey with a plurality of the popular vote and winning a majority of the electoral college.[207] Nixon successfully pursued southern whites and working class northerners, two New Deal coalition groups that Johnson had alienated.[209] Wallace, the candidate of many southern Democrats, chose to run as the American Independent Party nominee, and ultimately captured 13.5% of the popular vote and 46 electoral votes. Democrats maintained control of both houses of Congress, and while Nixon had campaigned on a new Vietnam policy, he had largely avoided talking about undoing the Great Society programs.[210]

Legacy and evaluation

Johnson's presidency left a lasting mark on the United States, transforming the United States with the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid, various anti-poverty measures, environmental protections, educational funding, and other federal programs.[83] The civil rights legislation passed under Johnson are nearly-universally praised for their role in removing barriers to racial equality.[83] Historians argue that Johnson's presidency marked the peak of modern liberalism in the United States after the New Deal era, and Johnson is ranked favorably by many historians.[211][212] Johnson's persuasiveness and understanding of Congress helped him to pass remarkable flurry of legislation and gained him a reputation as a legislative master.[213] Johnson was aided by his party's large Congressional majorities and a public that was receptive to new federal programs,[214] but he also faced a Congress dominated by the powerful conservative coalition of southern Democrats and Republicans, who had successfully blocked most liberal legislation since the start of World War II.[215] Though Johnson established many lasting programs, other aspects of the Great Society, including the Office of Economic Opportunity, were later abolished.[83] Johnson's handling of the Vietnam War remains broadly unpopular, and, much as it did during his tenure, often overshadows his domestic accomplishments.[213][216] The perceived failures of the Vietnam War nurtured disillusionment with government, and the New Deal coalition fell apart in large part due to tensions over the Vietnam War and the 1968 election.[83][101] Republicans won five of six presidential elections after Johnson left office, and Ronald Reagan came into office vowing to undo the Great Society, though Reagan and other Republicans were unable to repeal many of Johnson's programs.[83]

See also

References

- ↑ Califano Jr., Joseph A. (October 1999). "What Was Really Great About The Great Society: The truth behind the conservative myths". Washington Monthly. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ↑ Russell H. Coward (2004). A Voice from the Vietnam War. Greenwood. p. 25. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ↑ Epstein, Barbara (1993). Political Protest and Cultural Revolution: Nonviolent Direct Action in the 1970s and 1980s. University of California Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0520914469. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ↑ Transcript, Lawrence F. O'Brien Oral History Interview XIII, 9/10/86, by Michael L. Gillette, Internet Copy, Johnson Library. See: Page 23 at

- ↑ terHorst, Jerald F.; Albertazzie, Col. Ralph (1979). The Flying White House: the story of Air Force One. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan. ISBN 0-698-10930-9.

- ↑ Walsh, Kenneth T. (2003). Air Force One: a history of the presidents and their planes. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 1-4013-0004-9.

- ↑ Dallek, Robert (1998). Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and his Times, 1961–1973. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 49–51.

- ↑ "1963 Year in Review – Transition to Johnson". UPI. November 19, 1966. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ↑ "The National Archives, Lyndon B. Johnson Executive Order 11129". Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, p. 51

- ↑ Robert D. Chapman, "The Kennedy Assassination 50 Years Later." International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence (2014) 27#3 pp. 615–619.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, p. 58.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, p. 66.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, p. 67.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, p. 68.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, pp. 233–235.

- ↑ Hogue, Henry B. "Supreme Court Nominations Not Confirmed, 1789-August 2010" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Zelizer, Julian (2015). The Fierce Urgency of Now. Penguin Books. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, pp. 81–82.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Donnell, Michael (April 2014). "How LBJ Saved the Civil Rights Act". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 80-81.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 300-302.

- ↑ Zelizer, pg. 73.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Reeves 1993, pp. 521–523

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur (2002) [1965]. A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House. p. 973.

- ↑ Zelizer, pg. 60.

- 1 2 Caro, Robert. "The Passage of Power". p. 459

- ↑ Caro, Robert. "The Passage of Power". p. 462

- ↑ Dallek 1998, p. 116.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 98-99.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 101-102.

- ↑ Caro, Robert. "The Passage of Power". p. 463

- ↑ Purdum, Todd (9 April 2014). "LBJ's poignant paradoxes". Politico. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 121-124.

- 1 2 Zelizer, pp. 126-127.

- ↑ Zelizer, p. 128.

- ↑ Dallek 1998, p. 120.

- ↑ Zelizer, pp. 128-129.