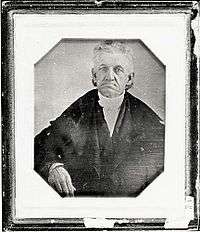

Lyman Beecher

| Lyman Beecher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

October 12, 1775 New Haven, Connecticut Colony |

| Died |

January 10, 1863 (aged 87) Brooklyn, New York |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Spouse(s) |

Roxana Beecher (desc.) Harriet Beecher (desc.) Lydia Beecher (desc.) |

| Children | Catharine E., William, Edward, Mary, Tommy, George, Harriet Elizabeth, Henry Ward, Charles, Frederick, Isabella, Thomas, James |

| Parent(s) | David and Esther Beecher |

Lyman Beecher (October 12, 1775 – January 10, 1863) was a Presbyterian minister, American Temperance Society co-founder[1] and leader, and the father of 13 children, many of whom became noted figures, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Beecher, Edward Beecher, Isabella Beecher Hooker, Catharine Beecher and Thomas K. Beecher.

Early life

Beecher was born in New Haven, Connecticut, to David Beecher, a blacksmith, and Esther Hawley Lyman. His mother died shortly after his birth, and he was committed to the care of his uncle Lot Benton,as W. Bray, and at the age of eighteen entered Yale, graduating in 1797. He spent 1798 in Yale Divinity School under the tutelage of his mentor Timothy Dwight.

Ministry

Ministry on Long Island in New York (1798 - 1810)

In September 1798, he was licensed to preach by the New Haven West Association, and entered upon his clerical duties by supplying the pulpit in the Presbyterian church at East Hampton, Long Island, and was ordained in 1799. Here he married his first wife, Roxana Foote. His salary was $300 a year, after five years increased to $400, with a dilapidated parsonage. To eke out his scanty income, his wife opened a private school, in which he was an instructor.[2] Beecher gained popular recognition in 1806, after giving a sermon concerning the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr.

Ministry in Litchfield, Connecticut (1810 - 1826)

Finding his salary wholly inadequate to support his increasing family, he resigned the charge at East Hampton, and in 1810 moved to Litchfield, Connecticut, where he was minister to the town's Congregational Church, and where he remained 16 years.[2] There he started to preach Calvinism.[3] He purchased the home built by Elijah Wadsworth and reared a large family.

Temperance

The excessive use of alcohol, known as "intemperance," was a source of concern in New England as in the rest of the United States. Heavy drinking even occurred at some formal meetings of clergy, and Beecher resolved to take a stand against it. About 1814 he delivered and published six sermons on intemperance. They were sent throughout the United States, ran rapidly through many editions in England, and were translated into several languages on the European continent, and had a large sale even after the lapse of 50 years.[2]

Unitarian Crisis and Women's Education

During Beecher's residence in Litchfield the Unitarian controversy arose, and he took a prominent part. Litchfield was at this time the seat of a famous law school and several other institutions of learning, and Beecher (now a doctor of divinity) and his wife undertook to supervise the training of several young women, who were received into their family. But here too he found his salary ($800 a year) inadequate.[2]

Ministry in Boston (1826 - 1832)

The rapid and extensive defection of the Congregational churches in Boston and vicinity, under the lead of William Ellery Channing and others in sympathy with him, had excited much anxiety throughout New England; and in 1826 Beecher was called to Boston's Hanover Church, where he began preaching against the Unitarianism which was then sweeping the area.[2]

Leadership of Lane Seminary in Cincinnati (1832 - 1852)

The religious public had become impressed with the growing importance of the great west; a theological seminary had been founded at Walnut Hills, near Cincinnati, Ohio, and named Lane Theological Seminary, after one of its principal benefactors, and a large amount of money was pledged to the institution on condition that Beecher accept the presidency, which he did in 1832.[2] His mission there was to train ministers to win the West for Protestantism. Along with his presidency, he was also professor of sacred theology, and pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church of Cincinnati (today, this congregation is Covenant First Presbyterian Church)[4] He served as a pastor for the first ten years of his Lane presidency.[2]

Beecher was also notorious for his anti-Catholicism and soon after his arrival in Cincinnati authored the nativist tract "A Plea for the West." His sermon on this subject at Boston in 1834 was followed shortly by the burning of the Catholic Ursuline sisters' convent there.

Lane Rebels

Beecher's term at Lane came at a time when a number of burning issues, particularly slavery, threatened to divide the Presbyterian Church, the state of Ohio, and the nation. The French Revolution of 1830, the agitation in England for reform and against colonial slavery, and the punishment by American courts of citizens who had dared to attack the slave trade carried on under the American flag, had begun to direct the attention of American philanthropists to the evils of American slavery, and an abolition convention met in Philadelphia in 1833. Its president, Arthur Tappan, through whose liberal donations Beecher had been secured to Lane Seminary, forwarded to the students a copy of the address issued by the convention, and the whole subject was soon under discussion.[2]

In 1834, students at Lane debated the slavery issue for 18 consecutive nights and many of them chose to adopt the cause of abolitionism. Many of the students were from the south, and an effort was made to stop the discussions and the meetings. Slaveholders from Kentucky came in and incited mob violence, and for several weeks Beecher lived in a turmoil, not knowing how soon the rabble might destroy the seminary and the houses of the professors. The board of trustees interfered during the absence of Beecher, and allayed the excitement of the mob by forbidding all further discussion of slavery in the Seminary, whereupon the students withdrew en masse.[2] Beecher also opposed the "radical" position of abolition and refused to offer classes to African-Americans. The group of about 50 students (who became known as the "Lane Rebels") who left the Seminary went to Oberlin College. The events sparked a growing national discussion of abolition that contributed to the beginning of the Civil War.

Heresy Trial Over New School Sympathies

Although earlier in his career he had opposed them, Beecher stoked controversy by advocating "new measures" of evangelism (e.g., revivals and camp meetings) that ran counter to traditional Calvinist understanding. These new measures at the time of the Second Great Awakening brought turmoil to churches all across America. Fellow pastor, Joshua Lacy Wilson, pastor of First Presbyterian (now, also a part of the Covenant First Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati) charged Beecher with heresy in 1835.

The trial took place in his own church, and Beecher defended himself, while burdened with the cares of his seminary, his church, and his wife at home on her death bed. The trial resulted in acquittal, and, on an appeal to the general synod, he was again acquitted, but the controversy engendered by the action went on until the Presbyterian church was divided in two. Beecher took an active part in the theological controversies that led to the excision of a portion of the general assembly of the Presbyterian church in 1837/8, Beecher adhering to the New School Presbyterian branch of the schism.

Move From Cincinnati to New York City (1852 - death in 1863)

After the slavery controversy, Beecher and his co-worker Stowe remained and tried to revive the prosperity of the Seminary, but at last abandoned it. The great project of their lives was defeated, and they returned to the East, where Beecher went to live with his son Henry in Brooklyn, New York, in 1852. He wished to devote himself mainly to the revisal and publication of his works. But his intellectual powers began to decline, while his physical strength was unabated. About his 80th year he suffered a stroke of paralysis, and thenceforth his mental powers only gleamed out occasionally.[2] After spending the last years of his life with his children, he died in Brooklyn in 1863 and was buried at Grove Street Cemetery, in New Haven, Connecticut.

Legacy

Beecher was proverbially absent-minded, and after having been wrought up by the excitement of preaching was accustomed to relax his mind by playing "Auld Lang Syne" on the violin, or dancing the "double shuffle" in his parlor.[2]

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati, Ohio was the home of her father Lyman Beecher on the former campus of the Lane Theological Seminary. Harriet lived here until her marriage. It is open to the public and operates as an historical and cultural site, focusing on Harriet Beecher Stowe, the Lane Theological Seminary and the Underground Railroad. The site also documents African-American history. The Harriet Beecher Stowe House is located at 2950 Gilbert Avenue, in Cincinnati, Ohio.[5]

Works

Beecher was the author of a great number of printed sermons and addresses. His published works are: Remedy for Duelling (New York, 1809), Plea for the West, Six Sermons on Temperance, Sermons on Various Occasions (1842), Views in Theology, Skepticism, Lectures on Various Occasions, Political Atheism. He made a collection of those of his works which he deemed the most valuable (3 vols., Boston, 1852).[2]

Personal life

In 1799 Beecher married Roxana Foote, the daughter of Eli and Roxana (Ward) Foote. They had nine children: Catharine E., William, Edward, Mary, Tommy, George, Harriet Elizabeth, Henry Ward, and Charles. Roxana died on September 13, 1816. The following year, he married Harriet Porter, and fathered four more children: Frederick C., Isabella Holmes, Thomas Kinnicut, and James Chaplin. After Harriet died on July 7, 1835, he married Lydia Beals born 17 Sept 1789, died 1869 daughter of Samuel Beals, previously married to Joseph Jackson 1779-10 Dec 1833 but had no more children.

References

- ↑ The Washingtonian Movement

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Beecher, Lyman". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Beecher, Lyman". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. - ↑ Beecher, Charles, ed. Autobiography, Correspondence, etc., of Lyman Beecher D.D., Vol. 1. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1866. p. 183.

- ↑ Beecher, Charles, ed. Autobiography, Correspondence, etc., of Lyman Beecher D.D., Vol. 2. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1865. p. 529.

- ↑ OHS - Places - Stowe House

External links

Media related to Lyman Beecher at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lyman Beecher at Wikimedia Commons Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Beecher, Lyman". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Beecher, Lyman". Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- The Beecher Tradition: Lyman Beecher

- Stowe house

- Stowe House official site

- Beecher Family Papers at Mount Holyoke College