Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro

| Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro (Phramongkolthepmuni) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Theravada, Maha Nikaya |

| Other names |

Luang Por Sodh Luang Pu Sodh Luang Pu Wat Paknam |

| Dharma names | Candasaro |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Thai |

| Born |

October 10, 1884 Song Phi Nong, Suphanburi, Thailand |

| Died |

February 3, 1959 (aged 73) Bangkok |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, Thonburi, Thailand |

Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro (10 October 1884 – 3 February 1959), also known as Phramongkolthepmuni (Thai: พระมงคลเทพมุนี), the abbot of Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, was the founder of the Thai Dhammakaya meditation school in 1916. As the former abbot of Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, he is often called Luang Pu Wat Paknam, meaning 'the Venerable Father of Wat Paknam'. He became a well-known meditation master during the interbellum and the Second World War, and played a significant role in the revival of Thai Buddhism during that period. He is considered by the Dhammakaya Movement to have rediscovered Vijja Dhammakaya, a meditation method believed to have been used by the Buddha himself. Since the 2000s, some scholars have pointed out that Luang Pu Sodh also played an important role in introducing Theravada Buddhism in the West, a point previously overlooked.[1][2][3]

Early life

Luang Pu Sodh was born as Sodh Mikaewnoi on 10 October 1884 to a relatively well-off family of rice merchants in Amphoe Song Phi Nong, Suphanburi, a province 102 km west of Bangkok. His father was called Ngen and his mother Soodjai. He received part of his schooling in the temple of his uncle, a Buddhist monk, when he was nine years old. He therefore became familiar with Buddhism from an early age. He also showed qualities of being an intelligent autodidact from an early age.[2][4][5] When his uncle moved to Wat Hua Bho, his uncle took him with him to teach. After a while his uncle left the monkhood, but Ngen managed to send Sodh to study with Luang Por Sub, the abbot of Wat Bangpla. This is where Sodh learnt Khmer. When he had finished his Khmer studies there, he returned home to help his father, who ran a rice-trading business, shipping rice from Suphanburi to sell to rice mills in Bangkok and Nakhon Chai Si District. At the age of fourteen, Sodh's father died, and he had to take responsibility for the family business, being the first son. This had an impact on him: thieves and other threats brought home to him the futility of the household life, and he desired to ordain as a monk. He had to take care of his family first though, and saved up money for them to be able to live without him.[2][4][6]

At the beginning of July 1906, aged twenty-two, he was ordained at Wat Songpinong in his hometown and was given the Pāli monastic name Candasaro.[7] Phra Candasaro studied both under masters of the oral meditation tradition as well as experts in scriptural analysis, which was exceptional during that period.[1][8]:36 In his autobiographical notes, he wrote that he practiced meditation every day, from the first day following his ordination.[9] After his third rainy season as a monk, Phra Candasaro traveled far and wide in Thailand to study scriptures and meditation practice with all the renowned masters of the time. He learnt about a broad range of things, and was in the habit of respecting all spiritual things. He studied scriptures at Wat Pho and learnt about meditation at eight centers, among which Wat Ratchasittharam.[1][10][4] At Wat Wat Ratchasittharam he studied a visualization meditation method with Luang Por Aium, and had his first breakthrough in meditation.[2] Crosby and Newell believe Wat Ratchasittharam to be crucial in Luang Pu Sodh's development of Dhammakaya meditation.[2][11]

The attainment of the Dhammakaya

Although Phra Candasaro had studied with many masters, and had mastered many important Pali texts, he was not satisfied. He withdrew himself in the more peaceful area of his hometown twice. Some sources suggest he also withdrew himself in the jungles to meditate more, but Newell doubts this.[12][13] In the eleventh year of his ordination, during the rains retreat (vassa), he stayed at Wat Botbon at Bangkuvieng, Nonthaburi Province. Wat Botbon was the temple where he used to receive education as a child, a temple known for its peacefulness.[14] In Luang Pu Sodh's autobiographical notes, he reflected to himself that he had been practising meditation for eleven long years and had still not understood the essential knowledge which the Buddha had taught. Thus, on the full-moon day of 1916, he sat down in the main shrine hall of Wat Botbon, resolving not to waver in his practice of sitting meditation, whatever might disturb his single-mindedness. That same night he attained in meditation what became known as the Dhammakaya, which marked the start of Dhammakaya meditation as a tradition.[15] Convinced that he had attained to the core of the Buddha's teaching, Phra Candasaro started a new chapter in his life. Phra Candasaro devoted the rest of his life to teaching and furthering the depth of knowledge of Dhammakaya meditation, a meditation method which he also called "Vijja Dhammakaya", 'the direct knowledge of the Dhammakaya'. Temples in the tradition of Wat Paknam Basicharoen, together called the Dhammakaya Movement, believe that this method was the method the Buddha originally used to attain Enlightenment, but was lost five hundred years after the Buddha passed away.[2][4] The event of the attainment of the Dhammakaya is usually described by the Dhammakaya movement in miraculous and cosmic terms.[16]

Life as an abbot

Phra Candasaro spend much time teaching. Even when he was still at Wat Pho, he would teach Pali language in his own kuti (monastic living space) to other monks and novices.[7] He had also restored an abandoned temple in his hometown Songphinong and set up a school for Dhamma studies for lay people in Wat Phrasriratanamahathat in Suphanburi. He enrolled for the reformed Pali examinations, but did not pass. He did not enroll again, even though he was a more than capable scholar: he believed that having obtained an official Pali degree, he might be recruited for administrative work in the Sangha (monastic community), which he did not aim for.[2][17] Nevertheless, because of his work, he was noticed by leading monks in the Sangha. Still in 1916, Somdet Wannarat, the monastic governor of Phasi Charoen, appointed Phra Candasaro as 'interim abbot' (Thai: ผู้รักษาการเจ้าอาวาส) of Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, located in Thonburi.[1][18] From then onward, he was usually referred to as "Luang Por Sodh" or "Luang Pu Sodh".

In 1916, Thonburi was not part of Bangkok yet, and had no bridge to connect it to Bangkok.[2] Wat Paknam faced social and disciplinary problems, and required a good leader. Luang Pu Sodh was able to change a temple that was neglected and almost vacant into a temple with hundreds of monks, a school for Buddhist studies, a government-approved school with a mundane curriculum, and a kitchen to make the temple self-sufficient.[7] Apart from monastic residents, the kitchen would also provide food for all the lay visitors of the temple.[19] Wat Paknam became a popular center of meditation teaching.[1][20] Besides developing a large community of monks in the temple (in 1959, five hundred monks),[15] he also set up a community of mae jis (nuns), with separate kutis and meditation rooms. Mae jis played an important role in Wat Paknam's teaching Dhamma and meditation.[21] Luang Pu Sodh promoted and enforced strict monastic discipline.[22] In the first period, however, his work was not appreciated by some lay people who, according to biographies, had illegal business with the temple and did not appreciate Luang Pu Sodh changing the temple. Once he was even shot at, though not hurt.[18] Soon after his appointment as temporary abbot, he was appointed fully as abbot of Wat Paknam, which he remained until his death in 1959.[1] For his life and work he was given two royal honorific names, that is Phrabhavanakosolthera (in 1949), Phramongkolratmuni (in 1955), and finally Phramongkolthepmuni (in 1957).[23][24] These titles were given late, due to the fact that the temple was not under royal patronage.[25]

Teaching meditation

During a ministry of over half-a-century, Luang Pu Sodh taught Dhammakaya meditation continuously, teaching meditation every Thursday and teaching Buddhism on Sundays and Uposatha days. At first, the Dhammakaya meditation method drew criticism from the Thai Sangha authorities, because it was a new method.[26] Discussion within the Sangha led to an inspection at Wat Paknam, but it was concluded that Luang Pu Sodh's method was correct.[15] In teaching meditation, Luang Pu Sodh would challenge others to meditate so that they might verify for themselves the claims which he made about Dhammakaya meditation. He organized a team of his most gifted meditation practitioners and set up a 'meditation factory of direct knowledge' (Thai: โรงงานทำวิชชา). These practitioners, mostly monks and mae chis, would meditate in an isolated location at the temple, in shifts for twenty-four hours a day, one shift lasting for six hours.[27] Their "brief" was to devote their lives to meditation research for the common good of society. In the literature of the Dhammakaya movement many accounts are found about Dhammakaya meditation solving problems in society and the world at large. For example, publications describe that Dhammakaya meditation was used during the Second World War to prevent Thailand from being bombed. Luang Pu Sodh also used meditation in healing people, for which he became widely known.[28][26][29] An often quoted anecdote is the story of Somdet Puean, the abbot of Wat Pho, who, after meditating with Luang Pu Sodh, recovered from his illness.[30] An important student in the meditation factory was Maechi Chandra Khonnokyoong, who Luang Pu Sodh once described as "first among many, second to none" in terms of meditation skill, according to the biography of Wat Phra Dhammakaya.[31]

Other achievements

Besides meditation, Luang Pu Sodh promoted the study of Buddhism as well. In this combination he was one of the pioneers in Thai Buddhism.[32] In 1939, Luang Pu Sodh set up a Pali Institute at Wat Paknam, which is said to have cost 2.5 million baht. Luang Pu financed the building through the production of amulets, which is common in Thai Buddhism. The kitchen which he build was the fulfillment of an intention which he had since his first years at Wat Pho, when he experienced difficulty in finding food. It also resulted in monks having more time to study the Dhamma.[2]

Luang Pu Sodh took part in the construction of the Phutthamonthon, an ambitious project of Prime Minister Phibun Songkhram in the 1950s. The park was built to host the 2500 Buddha Jayanti celebrations. Judging from the chapel at the centre of the Phutthamonthon, dedicated to Luang Pu Sodh and Dhammakaya meditation, as well as the amulets Luang Pu Sodh issued to raise funds for the park, Newell speculates Luang Pu Sodh assumed a significant role in building the park and had an important relation with PM Phibun.[33]

According to the biography by Wat Phra Dhammakaya, Luang Pu Sodh did not endorse "magical practices" that are common in Thai Buddhism, such as fortune-telling and spells. He did, however, often heal people through meditation, and Luang Pu Sodh's amulets were—and are still—widely venerated for their powers.[34]

Introducing Buddhism in the world

Luang Pu Sodh had a great interest to introduce Dhammakaya meditation outside of Thailand.[35] Wat Paknam already published international magazines and leaflets in the time Kapilavaddho started living under the guidance of Luang Pu Sodh. The periodical of the temple was in both Thai and English, and at certain occasions booklets would be published in Chinese as well. In old periodicals still remaining till today visits from high-standing monks from Japan and also monks from China have been recorded,[36] and Dhammakaya meditation is still passed on by Japanese Shingon Buddhists that used to practice at Wat Paknam.[37]

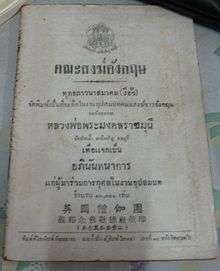

Luang Pu Sodh was one of the first Thai preceptors to ordain people outside Thailand as Buddhist monks. He ordained the Englishman William Purfurst (a.k.a. Richard Randall) with the monastic name "Kapilavaddho Bhikkhu" at Wat Paknam in 1954.[38] Kapilavaddho returned to Britain to found the English Sangha Trust in 1956.[39][40] Shine called Kapilavaddho the "man who started and developed the founding of the first English Theravada Sangha in the Western world"[41] He was the first Englishman to be ordained in Thailand, but disrobed in 1957, shortly after his mentor Phra Thitavedo had a disagreement with Luang Pu Sodh and left Wat Paknam. He ordained again in England, and became the director of the English Sangha Trust in 1967.[42][43] Luang Pu Sodh ordained another monk, Peter Morgan, with the name Pannavaddho Bhikkhu. After his death he would continue under the guidance of Ajahn Maha Bua. Phra Pannavaddho remained in the monkhood until his death in 2004. At the time of his death, he had ordained for the longest time of all westerners in Thailand.[44] A third monk, formerly known as George Blake, was a Brit of Jamaican origin. He was the first Jamaican to ordain as a Buddhist monk.[45] He ordained as Vijjavaddho. He later disrobed and became a well-known therapist in Canada.[46][47] The ordination of Vijjavaddho, Pannavaddho and another monk called Saddhavaddho (Robert Albison) was a major public event in Thailand, attracting an audience of 10,000 people. Namgyal Rinpoché (Leslie George Dawson), a teacher in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, also studied for a while under Luang Por Sodh, but did not ordain under him. Finally, mention can be made of Terrence Magness, who learnt Dhammakaya meditation at Wat Paknam as well, from the lay teacher Acharn Kalayawadee. He ordained under the name Suratano, and wrote a biography about Luang Pu Sodh.[4][48]

Death

Luang Pu Sodh was taken ill in 1956. He brought the work of the meditation workshop to an end by dismissing all of the meditation students except four or five of the most devoted nuns including Maechi Chandra Khonnokyoong and Maechi Thongsuk Samdaengpan. Luang Pu Sodh asked Maechi Chandra to keep on teaching Dhammakaya method, to pass it on to others. Luang Pu Sodh died in 1959, aged seventy-five.

Luang Pu Sodh's body was not cremated, but embalmed, so that after his death people would still come and support Wat Paknam.[2] In Wat Phra Dhammakaya a memorial hall was built in honor of Luang Pu Sodh.[49]

Publications

- Phramonkolthepmuni (2006) "Visudhivaca: Translation of Morradok Dhamma of Luang Phaw Wat Paknam" (Bangkok,60th Dhammachai Education Foundation) ISBN 978-974-94230-3-5

- Phramonkolthepmuni (2008) "Visudhivaca: Translation of Morradok Dhamma of Luang Phaw Wat Paknam", Vol.II (Bangkok,60th Dhammachai Education Foundation) ISBN 978-974-349-815-2

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dhammakāya Foundation 1996.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Newell 2008.

- ↑ Skilton, Andrew (2013-06-28). "Elective affinities: the reconstruction of a forgotten episode in the shared history of Thai and British Buddhism – Kapilavaḍḍho and Wat Paknam". Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14:1. London: 165.

Finally, had events been otherwise, the soḷasakaya meditation method, seen as somewhat marginal in its Thai context, might have become mainstream in the UK. As it is, it has been veiled by obscurity in the UK (even though it has been practised here throughout), despite its crucial historical role in the development of a native British bhikkhu-saṅgha.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bhikkhu 1960.

- ↑ Scott & 2009 66.

- ↑ Niamkham, Treetar (2012). Treetar's Story of Luang Por Wat Paknam: History of The Great Abbot of Wat Paknam and Dhammakaya Meditation. (self-published). Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- 1 2 3 Apinya 1998, p. 23.

- ↑ Dhammakaya Foundation, International Department (1998). The Life and Times of Luang Phaw Wat Paknam. Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation.

- ↑ Phramongkolthepmuni. อัตชีวประวัติ พระมงคงเทพมุนี (สด จนฺทสโร) หลวงปู่วัดปากน้ำ. มรดกธรรม, Book 1. Khlong Luang, Patumthani: Dhammakaya Foundation. pp. 29–39. ISBN 978-616-7200-36-1.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 81, 95.

- ↑ Crosby 2012.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 82.

- ↑ Bhikkhu 1960, p. 34.

- ↑ พระมงคลเทพมุนี (สด จนฺทสโร) วัดหลวงพ่อสดธรรมกายาราม [Phramongkolthepmuni, Sodh Candasaro-Wat Luang Phor Sodh Dhammakayaram]. วัดหลวงพ่อสดธรรมกายาราม สำนักปฏิบัติธรรมและโรงเรียนพระปริยัติธรรมแผนกบาลี ประจำจังหวัดราชบุรี (in Thai). สำนักปฏิบัติธรรมและโรงเรียนพระปริยัติธรรมแผนกบาลี ประจำจังหวัดราชบุรี ฯลฯ. 1999. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 24.

- ↑ Scott 2009, p. 79.

- ↑ Wichai 2003.

- 1 2 Scott 2009, p. 67.

- ↑ Mackenzie 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Newell 2010.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 84–5.

- ↑ Harvey, Peter (2013). An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. Cambridge University Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4.

- ↑ Fuengfusakul 1998, p. 24–5.

- ↑ Vasi 1998, p. 7.

- ↑ Mackenzie 2007, p. 32.

- 1 2 Scott 2009, p. 68.

- ↑ Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 24, 99.

- ↑ Cheng 2015.

- ↑ Mackenzie 2007, p. 34–5.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 94.

- ↑ Scott 2009, p. 72.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 107.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 84-5, 99-106.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 89.

- ↑ พุทธภาวนาสมาคม (งี้ฮั้ว). คณะสงฆ์อังกฤษ (ที่ระลึกในงานอุปสมนทคณะสงฆ์อังกฤษ). Bangkok: โรงพิมพ์วัฒนธรรม. pp. 1–10.

- ↑ Sivaraksa, Sulak (1987). "Thai Spirituality". Journal of the Siam Society. 75: 85.

- ↑ Rawlinson, A. (1994) The Transmission of Theravada Buddhism to the West, in: P. Masefield & D. Wiebe (Eds) Aspects of Religion: Essays in Honour of Ninian Smart (New York, Lang), p.360.

- ↑ Oliver, I. (1979) Buddhism in Britain (London, Rider & Company), p.102.

- ↑ Snelling, J. (1987) The Buddhist Handbook: A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching, Practice, History, and Schools (London, Rider), p.262.

- ↑ Shine, Terry. "Honour Thy Fathers" (PDF). Buddhanet. Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 91.

- ↑ Skilton, Andrew (2013-06-28). "Elective affinities: the reconstruction of a forgotten episode in the shared history of Thai and British Buddhism – Kapilavaḍḍho and Wat Paknam". Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14:1. London: 165.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 86, 91.

- ↑ ""Ordain Buddhist Monk"". JET Magazine. Johnson. 8 (26). 1955-11-03.

- ↑ Rinaldi, Luc. "'Are you sure you're not doing some African black magic?'". Maclean's. Rogers Media. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ "2014 Lifetime Achievement Award – Dr. B. George Blake". African Canadian Achievement Awards. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ Newell 2008, p. 90-91, 116.

- ↑ Scott 2009, p. 69.

Sources

- Cheng, Tun-jen; Brown, Deborah A. (2015), Religious Organizations and Democratization: Case Studies from Contemporary Asia: Case Studies from Contemporary Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-46105-0, retrieved 19 September 2016

- Crosby, Kate; Skilton, Andrew; Gunasena, Amal (12 February 2012), "The Sutta on Understanding Death in the Transmission of Borān Meditation From Siam to the Kandyan Court", Journal of Indian Philosophy, 40 (2): 177–198, doi:10.1007/s10781-011-9151-y

- Dhammakāya Foundation (1996), The Life & Times of Luang Phaw Wat Paknam (PDF), Bangkok: Dhammakāya Foundation, ISBN 978-974-89409-4-6

- Fuengfusakul, Apinya (1998). ศาสนาทัศน์ของชุมชนเมืองสมัยใหม่: ศึกษากรณีวัดพระธรรมกาย [Religious Propensity of Urban Communities: A Case Study of Phra Dhammakaya Temple] (published Ph.D.). Buddhist Studies Center, Chulalongkorn University.

- Mackenzie, Rory (2007), New Buddhist Movements in Thailand: Towards an understanding of Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Santi Asoke, Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 0-203-96646-5

- Bhikkhu (Terry Magness), Suratano (1960), The Life and Teaching of Chao Khun Mongkol-Thepmuni and The Dhammakāya (PDF), triple-gem.net, retrieved 2016-06-23

- Newell, Catherine Sarah (2008). Monks, meditation and missing links: continuity, "orthodoxy" and the vijja dhammakaya in Thai Buddhism (Ph.D. Thesis). London: Department of the Study of Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. pp. 15, 76, 99, 117, 270.

- Scott, Rachelle M. (2009), Nirvana for Sale? Buddhism, Wealth, and the Dhammakāya Temple in Contemporary Thailand, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1-4416-2410-9

- Vasi, Prawase (1998), สวนโมกข์ ธรรมกาย สันติอโศก [Suan Mokh, Thammakai, Santi Asok] (online ed.), Bangkok: Mo Chaoban Publishing

- Vuddhasilo, Phramaha Wichai (10 September 2003), ชีวประวัติหลวงพ่อวัดปากน้ำ ภาษีเจริญ พระภาวนาโกศลเถร [The history of Luang Phor Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, Phrabhavanakosolthera], in Singhon, บุคคลยุคต้นวิชชา [People from the beginning of Vijja] (in Thai), 3, Bangkok: Sukhumwit Printing, ISBN 9749149378

Biography

- Dhammakaya Foundation (1998). The Life & Times of Luang Phaw Wat Paknam, Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation. ISBN 978-974-89409-4-6

External links

- Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro

- Life&Time of Luang Pu Wat Paknum on YouTube

- Luang Phaw Wat Paknum

- The ordination of Robert Albison, George Blake and Peter Morgan