Lower Granite Dam

| Lower Granite Dam | |

|---|---|

|

View from the northwest | |

| Country | United States |

| Location |

Garfield / Whitman counties, Washington |

| Coordinates | 46°39′38″N 117°25′41″W / 46.66056°N 117.42806°WCoordinates: 46°39′38″N 117°25′41″W / 46.66056°N 117.42806°W |

| Construction began | July 1965 |

| Opening date | June 1975 [1] |

| Construction cost | $624,098,663[2] |

| Operator(s) | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Gravity dam |

| Impounds | Snake River |

| Height | 100 ft (30 m) |

| Length | 3,200 ft (980 m) |

| Spillway type | Service, gate-controlled |

| Spillway capacity | 850,000 cu ft/s (24,000 m3/s) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lower Granite Lake |

| Total capacity | 440,200 acre·ft (0.543 km3)[3] |

| Surface area | 8,900 acres (36.0 km2) |

| Normal elevation | 741 ft (226 m) |

| Power station | |

| Type | Run-of-the-river |

| Turbines | 6 × 135-155 MW units[4] |

| Installed capacity | 810 MW |

| |

Lower Granite Lock and Dam is a concrete gravity run-of-the-river dam in the northwest United States. On the lower Snake River, it bridges Whitman and Garfield counties in southeastern Washington.[5] The dam is located 22 miles (35 km) south of the town of Colfax, and 35 miles (56 km) north of Pomeroy.

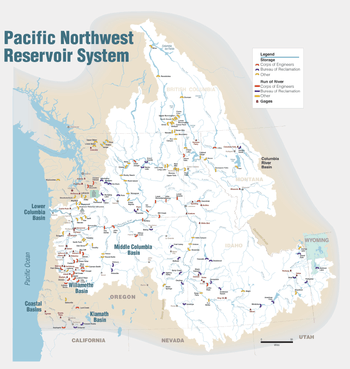

Lower Granite Dam is part of the Columbia River Basin system of dams. It was built and is operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Power generated is distributed by the Bonneville Power Administration.

Lower Granite Lake, which extends 39 miles (63 km) east to Lewiston, Idaho, is formed behind the dam, and allowed the city to become a port.[6] Lake Bryan, formed from Little Goose Dam, runs 37 miles (60 km) downstream from the base of the dam.

Construction

Construction began in July 1965, but was halted less than two years later due to lack of funding.[7] Work restarted in 1970, concrete was first poured in 1971,[8][9] and the main structure and three generators were completed in 1975.[1] An additional three generators were finished in May 1978,[10][11] bringing the generating capacity to 810 megawatts, with an overload capacity of 932 MW. The spillway has eight gates and is 512 feet (156 m) long. An 86-by-74-foot (26 m × 23 m) navigation lock was also included in construction.[2]

Fishery

Lower Granite Dam is the most upstream dam in the Snake River system that has a fish ladder to allow adult salmon and steelhead to migrate upstream. The Columbia River treaty tribes along with some environmental groups have recommended that this dam along with the other three lower Snake River dams be decommissioned and/or removed because of their impact on threatened and endangered chinook (threatened) and sockeye salmon (endangered) and steelhead (threatened) populations.,[12][13] A significant increase in the Sockeye Salmon return to the Columbia River in 2008 proved a pleasant surprise and raised hopes for increased salmon runs across the Lower Granite. Wildlife officials were not certain of the reason for the increased salmon return (Idaho Statesman, June 28, 2008) The Army Corps of Engineers has installed new devices such as removable spillway weirs in an attempt to make the dam less harmful to juvenile salmon.

There is also a juvenile bypass/collection facility that collects juvenile migrating salmon and steelhead so they can be transported downstream by barge.

- Navigation lock

- Single-lift

- Width: 86 feet (26 m)

- Length: 674 feet (205 m)

Asotin Dam

Authorized by Congress in 1962,[14] a fifth dam on the lower Snake River was proposed several miles upstream of Lewiston.[15] Concerns over its environmental and recreational impact stalled the Asotin Dam project,[16][17][18] and it was ultimately canceled in 1980.[19] The Asotin County public utilities district attempted to revive the project in 1988,[20] but it was quickly blocked by Congress,[21][22] and a law banning future dams was signed into law by President Reagan on November 17.[23][24]

Other proposed dams further upstream were not built either: the High Mountain Sheep Dam above the confluence with the Salmon River,[25] and the Nez Perce Dam, just below it.[15][26]

Road closed

Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, the road across the Lower Granite Dam was closed for over six years; it reopened for weekend traffic in May 2008.[27] The sand dune area downstream on the south shore (46°41′46″N 117°28′48″W / 46.696°N 117.48°W), accessed over the dam, was popular with local college students from Washington State University and the University of Idaho.[28]

See also

References

- 1 2 Harrell, Sylvia (June 20, 1975). "Dedication: Andrus brings a warning". Lewiston Morning Tribune. p. 1.

- 1 2 "LOWER GRANITE LOCK AND DAM--LOWER GRANITE LAKE". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "The Four Lower Snake River Dams". Bluefish.org. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "Lower Granite Dam". Washington.edu. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "The Columbia River System Inside Story" (PDF). BPA.gov. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "Snake River link to sea nearly complete". Ellensburg Daily Record. UPI. March 6, 1975. p. 3.

- ↑ "Engineers award contract for Lower Granite Dam". Lewiston Morning Tribune. May 14, 1970. p. 16.

- ↑ Pierce, Virginia (February 27, 1971). "Concrete pouring phase is begun at Lower Granite Dam site". Spokane Daily Chronicle. p. 5.

- ↑ Harrell, Sylvia (February 27, 1971). "Work on dam to continue despite shortage of funds". Lewiston Morning Tribune. p. 18.

- ↑ "Lower Granite power complex complete". Lewiston Morning Tribune. May 13, 1978. p. 6A.

- ↑ "Lower Granite Dam powerhouse finished". Spokane Daily Chronicle. May 16, 1978. p. 15.

- ↑ http://www.pcffa.org/fn-aug99.htm

- ↑ "5-Year Review: Summary & Evaluation of Snake River Sockeye, Snake River Spring-Summer Chinook, Snake River Fall-Run Chinook, Snake River Basin Steelhead" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ "Asotin Dam plan funds endorsed". Spokesman-Review. September 28, 1967. p. 6.

- 1 2 Hewlett, Frank (February 6, 1964). "High Mountain Sheep Dam project approved". Spokesman-Review. p. 1.

- ↑ "Asotin Dam criticized". Spokane Daily Chronicle. December 19, 1969. p. 19.

- ↑ "Luders heads drive to halt funds for dam". Spokane Daily Chronicle. March 12, 1973. p. 6.

- ↑ "Symms bill would halt Asotin Dam". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. March 14, 1973. p. 3.

- ↑ "Consortium ends Asotin Dam idea". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. August 27, 1980. p. 5.

- ↑ "Asotin Co. dam idea studied". Idahonian. Moscow, Idaho. Associated Press. June 17, 1988. p. 5A.

- ↑ "Senate passes Idaho dam ban". Spokane Chronicle. Associated. August 12, 1988. p. 9.

- ↑ Trillhaase, Marty (August 12, 1988). "McClure wins halt to Snake, Salmon dams". Lewiston Morning Tribune. p. 1A.

- ↑ Loftus, Bill (November 18, 1988). "Federal law bans proposed dam at Asotin". Lewiston Morning Tribune. p. 1A.

- ↑ "Bill will guarantee free-flowing Snake". Spokane Chronicle. wire reports. November 18, 1988. p. A2.

- ↑ "High Mountain Sheep Dam will rise in rugged land". Spokesman-Review. February 26, 1964. p. 20.

- ↑ "Dam dispute due in court". Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. January 29, 1967. p. 25.

- ↑ Rokyta, Devin (May 17, 2008). "Weekend crossings are again allowed at Lower Granite Dam". Moscow-Pullman Daily News. p. 1A.

- ↑ "Staying for the summer". Gem of the Mountains, University of Idaho yearbook. 1987. p. 71.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lower Granite Dam. |

- U.S. Army Corps Engineers: Lower Granite Dam

- Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

- Fish Passage Center Dam Counts

- History Link: Lower Granite Dam

- Boyer Park and Marina