Longfellow Bridge

| Longfellow Bridge | |

|---|---|

|

Bridge as seen from the Prudential Tower observatory | |

| Coordinates | 42°21′42″N 71°04′31″W / 42.361635°N 71.07541°WCoordinates: 42°21′42″N 71°04′31″W / 42.361635°N 71.07541°W |

| Carries |

|

| Crosses | Charles River |

| Locale | Boston, Massachusetts to Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Maintained by | Massachusetts Department of Transportation |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | steel rib Arch bridge |

| Total length | 1,767.5 feet (538.7 m)[1] |

| Width | 105 feet (32 m)[1] |

| Longest span | 188.5 feet (57.5 m)[1] |

| History | |

| Construction begin | July 1900[1] |

| Opened | August 3, 1906 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 28,600 cars and 90,000 mass-transit passengers |

| |

The Longfellow Bridge (also known to locals as the "Salt-and-Pepper Bridge"[2] or the "Salt-and-Pepper-Shaker Bridge"[3] due to the shape of its central towers) carries the Route 3 roadway, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Red Line trains, bicycle, and pedestrian traffic. The structure spans the Charles River to connect Boston's Beacon Hill neighborhood with the Kendall Square area of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The bridge falls under the jurisdiction and oversight of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT).[4] The bridge carries approximately 28,600 cars and 90,000 mass-transit passengers every weekday.[5] A portion of the elevated Charles/Massachusetts General Hospital rapid transit station lies at the eastern end of the bridge, which connects to Charles Circle.

Description

Longfellow Bridge is a combination railway and highway bridge. It is 105 feet (32 m) wide, 1,767 feet 6 inches (538.73 m) long between abutments, and nearly one-half mile in length, including abutments and approaches. It consists of eleven steel arch spans supported on ten masonry piers and two massive abutments. The arches vary in length from 101 feet 6 inches (30.94 m) at the abutments to 188 feet 6 inches (57.45 m) at the center, and in rise from 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m) to 26 feet 6 inches (8.08 m). Headroom under the central arch is 26 feet (7.9 m) at mean high water.

The two large central piers, 188 feet (57 m) long and 53 feet 6 inches (16.31 m) wide,[1] feature four carved, ornamental stone towers that provide stairway access to pedestrian passageways beneath the bridge. Its sidewalks were originally both 10 feet (3.0 m) wide, but as of 2013, for unknown reasons, the upstream sidewalks were narrower than the downstream ones.

History

The first river crossing at this site was a ferry, first run in the 1630s.[6] The West Boston Bridge (a toll bridge) was constructed in 1793 by a group of private investors with a charter from the Commonwealth. At the time, there were only a handful of buildings in East Cambridge. The opening of the bridge caused a building boom along Main Street in Cambridge, which connected the bridge to Old Cambridge. In East Cambridge, new streets were laid out and land was reclaimed from the swamps along the Charles River.[7] The Cambridge and Concord Turnpike (now Broadway) was connected to the bridge's western approach around 1812. The bridge became toll-free on January 30, 1858.[8]

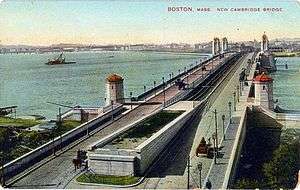

In 1898 the Cambridge Bridge Commission was created to construct "a new bridge across Charles River, to be known as Cambridge Bridge, at, upon, or near the site of the so-called West Boston Bridge... suitable for all the purposes of ordinary travel between said cities, and for the use of the elevated and surface cars of the Boston Elevated Railway Company." At its first meeting on June 16, 1898, Willam Jackson was appointed Chief Engineer; shortly afterward Edmund M. Wheelwright was appointed Consulting Architect. Both then traveled to Europe, where they made a thorough inspection of notable bridges in France, Germany, Austria and Russia. Upon their return, they prepared studies of various types of bridges, including bridges of stone and steel arch spans.

Although both state and national regulations at the time required a draw bridge, it became evident that a bridge without a draw would be cheaper, better-looking, and avoid disruption to traffic. The state altered its regulations accordingly, and after the War Department declined to follow suit, the United States Congress drew up an act permitting the bridge, which President William McKinley signed on March 29, 1900. Construction began in July 1900; the bridge opened on August 3, 1906, and was formally dedicated on July 31, 1907.[1]

Wheelwright had been inspired by the 1893 Columbian Exposition and was attempting to emulate the great bridges of Europe. Four large piers of the bridge are ornamented with the prows of Viking ships, carved in granite. They refer to a purported voyage by Leif Eriksson up the Charles River circa 1000 AD, as promoted by Harvard professor Eben Horsford. The piers are also decorated with the city seals of Boston and Cambridge.

The Cambridge Bridge was renamed as the Longfellow Bridge in 1927[9] by the Massachusetts General Court to honor Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who had written about the predecessor West Boston Bridge in his 1845 poem "The Bridge".

There are pedestrian stairs on both sides of the bridge at both ends adorned with stone towers. Originally, these led to the Charles River shoreline, and on the Cambridge side they still do. On the Boston side, the construction of Storrow Drive in 1950-51 moved the shoreline, so that the stairs now lead to isolated parcels of land cut off from the river by Storrow Drive. There is no way to exit the upstream parcel, due to an off-ramp; the downstream one includes a crosswalk past another off-ramp. To reach the Charles River Esplanade, pedestrians must now proceed along the sidewalk to the end of the bridge, and use a wheelchair-accessible, pedestrian bridge at Charles Circle slightly south of the Longfellow Bridge.

Until 1952, the central road traffic lanes of the bridge also contained tracks which connected what is now known as the Blue Line, running from crossovers at the Cambridge end from the Red Line subway tracks, across the bridge and into Boston to the North Russell Street Incline of the Blue Line subway. Before the Orient Heights Blue Line yards were built, major repairs to that line's trains were performed at the former Eliot Square carbarns in Cambridge. For more details on this historic Red/Blue Line connection, see Blue Line (MBTA)#History.[10]

Neglect and rehabilitation

The Longfellow Bridge, like many bridges in the Commonwealth,[11] deteriorated into a state of disrepair. Between 1907 and 2011, the only major maintenance conducted on the bridge had been a small 1959 rehabilitation project and some lesser repairs done in 2002.[12]

On May 1, 2007, a fire broke out under the bridge, ignited by an unextinguished cigarette. The fire caused the bridge to be shut down to vehicle and train traffic,[13] and also severed Internet2 connectivity to Boston, causing problems with the Chicago-New York OC-192 route, according to the Internet2 blog.[14]

In the summer of 2008, two state employees stole 2,347 feet (715 m) of decorative iron trim that had been removed from the bridge for refurbishment, and sold it for scrap. The men, one of whom was a Department of Conservation and Recreation district manager, were charged with receiving $12,147 for the historic original parapet coping. The estimated cost to remake the pieces, scheduled for replication by 2012, was over $500,000.[15] The men were later convicted in September 2009.[16]

Also that summer, the western sidewalk and inner traffic lane were both closed, the Red Line subway was limited to 10 miles per hour (16 km/h), and Fourth-of-July fireworks-watchers were banned from the bridge, all because of concerns that the bridge might collapse under the weight and vibration of heavy use.[6] The speed restriction was lifted in August 2008, and the lane and sidewalk were reopened later on.

On August 4, 2008 Governor Deval Patrick signed into law a $3 billion Massachusetts bridge repair funding package he had sponsored.[17] Bond funds are to be used to pay for the rehabilitation of the Longfellow, with a preliminary cost estimate of $267.5 million.[18] If bridge maintenance had instead been performed regularly, the total estimated historical cost would have been about $81 million.[19] Design began in Spring 2005; construction was expected to begin in Spring 2012 and end in Spring 2016.[18]

Ownership and management of the overhaul was transferred from the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) to the new Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) on November 1, 2009, along with other DCR bridges.[20]

Emergency repairs

The condition of the bridge was determined to be so bad that the state could not wait for development of a full restoration plan. A $17 million contract was signed with SPS New England Inc for interim repairs.[21] Crews began work in August 2010 that involved improving sidewalks on the approaches to bring them up to ADA compliance. In March 2011 crews began structural inspections for Phase II and cleaning of the stone masonry piers. MassDOT announced in May 2011 that work would begin on stripping and cleaning rust from steel arch ribbons that had not been painted since 1953. Crews were to apply paint primer to the arch ribbons and evaluate them for future major rehabilitation. All work was expected to be completed by December 2011.[22]

Major reconstruction project

A $255 million project started construction in Summer 2013 to replace structural elements of the bridge, and restore its historic character.[23] The project is expected to require at least 25 weekend shutdowns of MBTA Red Line subway service to accommodate construction, including multiple temporary relocations of the rapid transit tracks.[24] Outbound road traffic (from Boston to Cambridge) was detoured from the bridge for all 3 years of expected construction. A single lane of inbound traffic is expected to be available for the duration of the project, but it may be restricted to only buses at certain hours. A computer animation movie released by MassDOT shows the complex 6-stage rehabilitation process in great detail, including temporary installation of a "shoo-fly track" to allow the permanent railbed at the midline of the span to be rebuilt.[25]

The design/build phase of the bridge is to be completed by the joint venture team of contractors White-Skanska-Conslgli under supervision by MassDOT.[26] Bridge Architect Miguel Rosales of Boston-based transportation architects Rosales + Partners provided the conceptual design, bridge architecture, and aesthetic lighting design. Preliminary design engineering was performed by Jacobs Engineering. STV, Inc. is the final design engineer and engineer of record. When complete, the bridge will have widened sidewalks and bike lanes,[23][24] with two motor vehicle lanes inbound (towards Boston), but only a single lane outbound (towards Cambridge).[27]

The Longfellow Bridge Restoration and Rehabilitation project was scheduled for completion in 2016, but the completion date was extended to December 2018, due in part to historic restoration requiring obsolete construction techniques such as riveting.[27] In August 2016, the outbound side of the bridge was completely closed to all traffic, including pedestrians and cyclists, in order to complete work sooner. This measure may allow the bridge to be fully reopened in June 2018.[28]

Gallery

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jackson, William (1909). Report of the Cambridge bridge commission and report of the chief engineer upon the construction of Cambridge bridge. Printing department. Cambridge Bridge Commission. p. 42. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ Angelo, William J. (June 6, 2007). "Salt and Pepper Bridge Slated For Major Rehab in Boston". Engineering News-Record. The McGraw-Hill Companies. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ Howe, Peter J. (January 19, 2008). "Heavy vehicles banned from bridge's left lanes". The Boston Globe. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Bridge Rehabilitation, Cambridge Street over the Charles River". Mhd.state.ma.us. Archived from the original on 2011-04-10. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- ↑ "MassDOT Highway Division: Longfellow Bridge Rehabilitation Project". Boston, Massachusetts: MassDOT (Commonwealth of Massachusetts). 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-08-04. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

The bridge presently carries 28,000 motor vehicles, 90,000 transit users, and significant numbers of pedestrians and bicyclists each day.

- 1 2 With bridges shaky, what if Boston lost its link to Cambridge? Boston Globe, 3 Aug 2008. Archived May 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ History of Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1630-1877 by Lucius Robinson Paige. p. 176 and thereafter

- ↑ History of Cambridge, p. 201-202

- ↑ Haglund, Karl (September 16, 2002). Inventing the Charles River. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-262-08307-2. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ↑ Clarke, Bradley H. (198). The Boston Rapid Transit Album. Boston Street Railway Association. p. 14.

- ↑ "Report: Mass. Road And Bridge Repair Is Poor". wbztv.com. Associated Press. 2007-07-31. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ↑ Westerling, David & Steve Poftak, A Legacy of Neglect, Boston Globe Op Ed., A11 (Jul 31, 2007).

- ↑ Firehouse.com

- ↑ "Internet2 blog". I2net.blogspot.com. 2007-05-02. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ Ebbert, Stephanie (2008-09-12). "Case of the purloined ironwork". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ Ellement, John R. (2009-09-16). "Pair get jail for iron theft at bridge". Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts: New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ↑ Viser, Matt (2008-08-05). "Patrick signs $3b bill to fix bridges". boston.com. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- 1 2 "Accelerated Bridge Program (ABP) Plan - By Locality" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ Ross, Casey, Longfellow's long list of woes Archived June 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Boston Herald Special Report, (Jan 11, 2008).

- ↑ "90 Day Integration Report - September 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ↑ "Longfellow Bridge". Massdot.state.ma.us. Archived from the original on 2010-10-17. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- ↑ Brown, Sara (April 12, 2011). "Beacon Hill gets a Longfellow Bridge update". The Boston Globe.

- 1 2 MassDOT. "Longfellow Bridge". Accelerated Bridge Program. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- 1 2 Powers, Martine (February 28, 2013). "Longfellow Bridge repairs, disruption to start in summer". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ MassDOT. "Longfellow Bridge Construction Animation". youmovemass. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ MassDOT. "MASSDOT BOARD APPROVES CONTRACTS FOR REHABILITATION OF LONGFELLOW AND WHITTIER BRIDGES". Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- 1 2 Dungca, Nicole (July 29, 2015). "Longfellow Bridge construction extended until late 2018". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ Dungca, Nichole (August 31, 2016). "Rebuilt Longfellow Bridge may reopen by June 2018". Boston Globe. Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

Further reading

- Jackson, William (1909). Report of the Cambridge bridge commission and report of the chief engineer upon the construction of Cambridge bridge. Printing department. Cambridge Bridge Commission. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- Freeman, Dale H. (2000). A changing bridge for changing times : the history of the West Boston Bridge, 1793-1907 ; a thesis. University of Massachusetts Boston. ASIN B0006RH37A.

- Seitinger, Susanne (2002). "Lookin' Good, Feelin' Good: the transformation of Charles Circle" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- Moskowitz, Eric (July 25, 2010). "Linking cities and eras". Boston Globe. pp. Pgs. 1–4. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Longfellow Bridge. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Longfellow Bridge Rehabilitation. |

- Longfellow Bridge at Structurae

- "The Bridge", poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Longfellow Bridge, Spanning Charles River at Main Street, Boston, Suffolk County, MA

Closures

- Daniel, Mac (January 22, 2006). "Longfellow Bridge lane to close". The Boston Globe.

- "Defects lead to closure of a Longfellow Bridge sidewalk". The Boston Globe. June 6, 2008. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008.

- Ebbert, Stephanie (June 7, 2008). "Longfellow Bridge is off-limits July 4th". The Boston Globe.

- Ebbert, Stephanie (June 26, 2008). "Two lanes closed on Longfellow Bridge". The Boston Globe.