Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock

| Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Argued October 23, 1902 Decided January 5, 1903 | |||||||

| Full case name |

Lone Wolf, Principal Chief of the Kiowas, et al., Appellants., v. Ethan A. Hitchcock, Secretary of the Interior, et al., Appellees. | ||||||

| Citations |

187 U.S. 553, 23 S.Ct. 216, 47 L.Ed. 299 | ||||||

| Prior history | 19 App. D. C. 315 | ||||||

| Holding | |||||||

| Congress has plenary power to unilaterally abrogate treaty obligations between the United States and Native American tribes. | |||||||

| Court membership | |||||||

| |||||||

| Case opinions | |||||||

| Majority | White, joined by Brewer, Brown, Fuller, Holmes, Peckham, McKenna, Shiras | ||||||

| Concurrence | Harlan | ||||||

| Laws applied | |||||||

| U.S. Constitution, Article V | |||||||

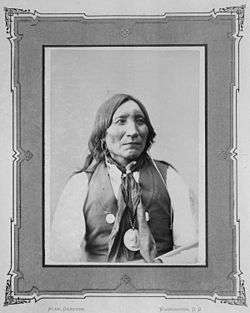

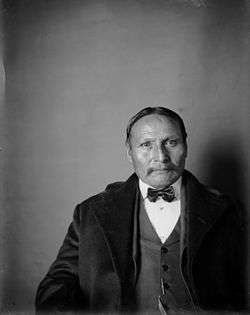

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903) was a United States Supreme Court case brought against the US government by the Kiowa chief Lone Wolf, who charged that Native American tribes under the Medicine Lodge Treaty had been defrauded of land by Congressional actions in violation of the treaty.

The Court declared that the "plenary power" of the United States Congress gave it authority to unilaterally abrogate treaty obligations between the United States and Native American tribes. The decision marked a departure from the holdings of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. 1 (1831), and Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832), which had shown greater respect for the autonomy of Native American tribes.

Background

Tribes

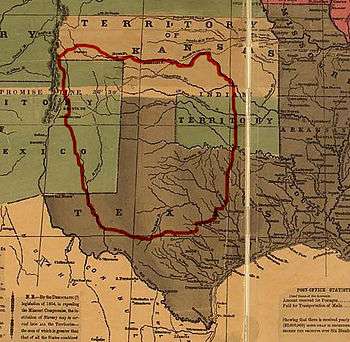

The Kiowa tribe is a Native American tribe that has historically inhabited the southern Great Plains what is now present-day Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, and New Mexico.[1] Originally from the northern great plains along the Platte River, and under pressure from other tribes,[2] they eventually moved and settled south of the Arkansas River primarily in present-day Oklahoma.[fn 1] The Kiowa had a long history of close association and alliance with the Kiowa-Apache or Plains Apache.[4] Around 1790, the Kiowa also formed an alliance with the Comanche and formed a barrier to European-American incursions into their territories.[5] This alliance made travel on the Santa Fe Trail hazardous, with attacks on wagon trains beginning in 1828 and continuing thereafter.[6]

Treaties

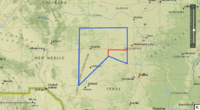

In 1837 at Fort Gibson, leaders of the Kiowa tribe signed their first treaty[7] with the United States.[fn 2] By 1854, the need for another treaty became apparent, and the United States entered into a treaty[9] with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Kiowa-Apache (KCA) at Fort Ackinson, Indian Territory.[10] The treaty did not specifically designate a reservation, but was, for the most part, an extension of the 1837 treaty. There was an attempt to place some of the tribes on a reservation on the Brazos River in Texas near Fort Belknap, under Indian Agent Robert S. Neighbors.[11] By 1858, Neighbors resolved to move the reservation into Indian Territory.[fn 3] By August 1859, Neighbors had moved the Indians from the Brazos Reservation to Indian Territory, south of the Washita River near Fort Cobb.[fn 4][14] In 1865, near present-day Wichita, Kansas, the three tribes signed another treaty[15] that provided for the reservation in present-day Oklahoma and Texas.[16] Finally, in 1867, the tribes agreed to the Medicine Lodge Treaty.[17] This treaty provided for a much smaller reservation, and stipulated that whites were not allowed to encroach on the reservation. Also, to further reduce the reserve's land would require the approval of three-fourths of the tribal members.[fn 5][19]

Assimilation period

Within one year, the United States breached the treaty when General William T. Sherman ordered all the tribes to Fort Cobb, withheld the treaty payments to them, and requested an order declaring that all hunting rights be forfeited.[fn 6] At the same time, Indian agents were trying to undermine tribal authority as the buffalo herds were being eliminated by white hunting.[21] Two new leaders emerged during this time period, Quanah Parker[fn 7] and Lone Wolf (the younger)[fn 8] Following his defeat at the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon, Parker settled down and began to adopt white ways.[23] Lone Wolf and his followers continued to resist assimilation policies.[24] Many of the old tribal leaders had been arrested and imprisoned when they left the reservation to hunt, and war leaders such as Lone Wolf (the elder) started to pass away from old age and disease.[fn 9]

During this same period, as the tribes had been unsuccessful at farming it, the KCA found a way to make the land pay by leasing it to cattlemen for grazing.[26] By 1885, about 1,500,000 acres (610,000 ha) were being used to graze about 75,000 cattle, with an annual payment to the tribes of $55,000.[27] At the same time, whites living just outside the reservation boundary were coming onto it to take timber and other goods, resulting in the tribes forming a police force to protect their property from white theft.[28]

The Jerome Commission

In 1892, the United States sent the Jerome Commission, consisting of David H. Jerome, Alfred M. Wilson, and Warren G. Sayre, to meet with the Kiowa to convince them to turn over most of their reserve for white settlement in return for $2 million.[29][30] Lone Wolf spoke out in opposition to the allotment, saying:

Now we have several good schools on the reservation, and to them we intend to send our children, where they will be taught the arts of manual labor. There they will learn to live like white people, and soon then they will be civilized. We advised our people to build houses, and quite a number of them today are living in houses. Some are building and still others are contemplating building. For that reason, because we are making such rapid progress, we ask the commission not to push us ahead too fast on the road we are to take. This morning in council the Comanches decided not to sell the country, and the Kiowas decided not to sell the country, and the Apaches decided not to sell the country. And I do not wish the commission to force us. That is all.[31]

After over a week of negotiations, terms were set so that each member would receive 160 acres. The tribes would receive $2 million of which $250,000 would be paid to members, with the remaining money to be held in trust for the tribes at 5% interest.[32] The commission immediately began to collect signatures and, just as quickly, allegations of fraud arose. Joshua Givens, an interpreter, was widely suspected of being dishonest. He was accused of forcing some members to sign and tricking others into thinking they were signing a document opposing the agreement.[33] By now, the tribes were almost unanimous in their opposition to the agreement, asked to see the document, and requested that their signatures be removed. Lone Wolf later stated that this was refused and that they were threatened with violence.[34] Jerome left the reservation with what the government claimed was the approval of three-quarters of the tribe.[35]

Congress

With the validity of the agreement in question, the tribes, joined by the Indian Rights Association (IRA) and local ranchers, lobbied against its ratification by Congress.[fn 10][37] The IRA wrote letters to Senators, stating that the agreement was: "utterly destructive of that honor and good faith which should characterize our dealings with any people, and especially with one too weak to enforce their rights as against us by any other mean as than an appeal to our sense of justice."[38] The Secretary of the Interior[fn 11] informed Congress that the allotment would be devastating to the tribes, as the land was not suited to farming, and the amount of land allotted would not allow them sufficient land to graze cattle.[40] A bill was introduced in 1892 to ratify the agreement, but failed to receive the necessary votes. It was reintroduced every year until it passed in 1900, eight years later.[41] The agreement finally passed when the Rock Island Railroad agree to set aside an additional 480,000 acres of pastureland for the tribes to hold in common.[42]

Lower courts

At the ratification of the agreement, a delegation of tribal leaders[fn 12] traveled to Washington, D.C. and requested a meeting with President William McKinley.[44] McKinley's position was that the tribes must conform to the decision of Congress.[45] Parker and the other principal chiefs accepted that the fight against allotment was over but Lone Wolf continued to argue against accepting allotment.[46] In 1901, Lone Wolf and others hired William M. Springer, a former federal judge and congressman.[47]

Supreme Court of the District of Columbia

On June 6, 1901, Springer filed suit in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, which is a different court than the United States Supreme Court.[48] The plaintiffs asked for an injunction to stop the opening of KCA lands to settlement and the allotment of the land.[49] Springer argued that the Jerome agreement deprived the tribes of their lands without due process and in violation of the Constitution by breaking the treaty with the tribes.[50] Springer alleged that the KCA were duped into signing the agreement and that it was not signed by three-quarters of the members as required by the treaty,[fn 13] that the KCA had protested the agreement from the beginning, and that the version which Congress ratified was different from the version signed by the KCA.[fn 14][53] While the suit was being heard, on August 6, 1901, the government began to sell off the tribes' surplus land.[54] Judge A.C. Bradley ruled against Lone Wolf, holding that Congress had the authority to allot the land, citing United States v. Kagama.[55][56]

Circuit Court of Appeals

Springer then appealed to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.[57] By the time that court heard the appeal, the reservation land had been allotted and excess land sold.[58] The D.C. Circuit ruled that the question was not justiciable, rather it was a political question which had to be decided by Congress.[59] The Court held that an act of Congress must prevail over any specific article in a treaty with an Indian tribe.[60] The court further held that, in any event, the land did not belong to the tribe. It was controlled by the United States, with Indians as mere occupants.[61] The Circuit Court affirmed the decision of the lower court.[62]

Supreme Court

Arguments

At this point, the IRA hired another attorney, Hampton L. Carson,[fn 15] to take the lead from Springer.[64] The arguments remained the same as they had in the lower courts: that the tribes were being deprived of their land without due process. The attorneys noted that the United States had never deprived a tribe of its land without some form of consent by the tribe.[65] Carson and Springer highlighted Worcester v. Georgia[66] and the Indian canon of construction in their arguments.[67]

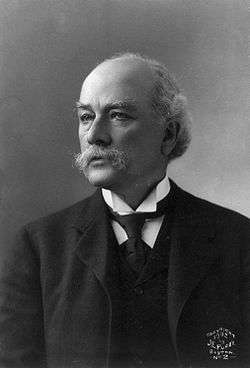

Willis Van Devanter[fn 16] argued the case for the United States, taking the position that Congress had the power to abrogate the treaty at will. Devanter cited Kagama as authority for Congress having plenary power over Indian matters.[69]

Opinion of the court

Justice Edward White delivered the opinion of the unanimous court. The Court held that Congress had the authority to void treaty obligations with Native American tribes because it had an inherent plenary power,[70] noting:

"Authority over the tribal relations of the Indians has been exercised by Congress from the beginning, and the power has always been deemed a political one, not subject to be controlled by the judicial department of the government."[71]

The decision was based, among other things, on a paternalistic view of the United States' relationship with the tribes:

"These Indian tribes are the wards of the nation. They are communities dependent on the United States. Dependent largely for their daily food. Dependent for their political rights. They own no allegiance to the states, and receive from them no protection. Because of the local ill feeling, the people of the states where they are found are often their deadliest enemies. From their very weakness and helplessness, so largely due to the course of dealing of the Federal government with them and the treaties in which it has been promised, there arises the duty of protection, and with it the power. This has always been recognized by the executive and by Congress, and by this court, whenever the question has arisen."[72]

The decision presented American Indians as inferior in race, culture, and religion:

"It is to be presumed that in this matter the United States would be governed by such considerations of justice as would control a Christian people in their treatment of an ignorant and dependent race. Be that is it may, the propriety or justice of their action towards the Indians with respect to their lands is a question of governmental policy, and is not a matter open to discussion in a controversy between third parties, neither of whom derives title from the Indians."[73]

White held that requiring tribal consent would actually hurt the tribes, and that the tribes should presume that Congress would act in good faith to protect tribal needs.[74]

Justice John Marshall Harlan concurred in the judgment, but did not author a separate opinion.

Subsequent developments

This was one of the first cases where an Indian tribe went to court rather than resort to warfare to resolve an issue.[fn 17][76] It was also a major defeat for the tribes. Reports show that ninety percent of the land allotted to tribal members was lost by them to settlers.[77] By the 1920s, the KCA tribes were impoverished, with an unemployment rate of sixty percent.[78]

By 1934, approximately 90,000,000 acres (36,000,000 ha), which was two-thirds of Indian lands, had been transferred to settlers.[79] Until the Meriam Report was published showing the destructive effects of the policy, the allotment process continued unchecked.[80] By the time Congress ended allotment, the KCA land went from 2,900,000 acres (1,200,000 ha) to about 3,000 acres (1,200 ha).[81] Also, the Court's ruling meant that the only recourse left for Indian tribes to use to resolve land disputes was Congress.[82] Indians were not eligible to bring a case in the United States Court of Claims under the Tucker Act,[83] and were limited to actions in often hostile state courts.

Legally, scholars have compared Lone Wolf to the infamous Dred Scott case,[84] and universally condemned the decision.[85]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ The Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache controlled an area bounded in the north by the Arkansas River, in the south by the Wichita Mountains and the headwaters of the Red River.[3]

- ↑ This treaty called for peace between the tribe and the United States, and for free passage of U.S. citizens through tribal lands while en route to or from the Republic of Texas or Mexico.[8]

- ↑ This was due to the repeated attacks by white settlers on Indians, including the murder of seven Indians as they slept and an attack by several hundred whites under Captain John R. Baylor on the reservation.[12]

- ↑ Within one month of the move, Neighbors was shot in the back with a shotgun and murdered by a man who felt Neighbors had protected the Indians.[13]

- ↑ Lone Wolf (the elder) did not sign the treaty because he did not believe the U.S. would honor it.[18]

- ↑ The treaty guaranteed the tribes the right to hunt their traditional lands south of the Arkansas River, and the local agent protested that the tribes had done nothing to justify Sherman's actions.[20]

- ↑ Parker was Comanche and Lone Wolf was Kiowa.

- ↑ Originally named Mamay-day-te, he was the adopted son of Lone Wolf (the elder).[22]

- ↑ Lone Wolf (the elder) contracted malaria while being held in Florida. The others included Satank (Sitting Bear), Kicking Bird, and Satanta (White Bear).[25]

- ↑ The local ranchers leased the grasslands from the tribes and did not want it opened to settlement.[36]

- ↑ Both Cornelius Newton Bliss and his successor, Ethan A. Hitchcock, were opposed to the agreement, believing it would not help the tribes become self-sufficient.[39]

- ↑ The leaders were Eschiti, Parker, William Tivis, and Delos Lone Wolf (nephew of Lone Wolf).[43]

- ↑ The agreement was signed by 456 members, and at the time there were 639 members of the tribe, putting the agreement at 23 signatures short. This number was verified by Secretary Hitchcock.[51]

- ↑ Part of the change in the ratified version was the removal of allotments to white men who were connected to the commission, but not tribal members.[52]

- ↑ Carson was a professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania and was later the Pennsylvania Attorney General and President of the American Bar Association.[63]

- ↑ Devanter was later appointed to fill the Supreme Court seat held by Justice White.[68]

- ↑ The last uprising resulted in the surrender, then massacre, of over 200 Lakota men, women, and children at Wounded Knee in 1890.[75]

References

- ↑ Carl Waldman, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes 132-34 (2009).

- ↑ Angela R. Riley, The Apex of Congress' Plenary Power over Indian Affairs: The Story of Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, in Indian Law Stories 193 (Carole Goldberg, Kevin K. Washburn, & Philip P. Frickey eds., 2011); James Mooney, Calendar History Of The Kiowa Indians 153 (Kessinger Publishing 2006) (1901).

- ↑ Mooney, at 153-54.

- ↑ Mooney, at 156; Waldman, at 433.

- ↑ David La Vere, The Texas Indians 147 (2003); Waldman, at 133; John R. Wunder, Why Native Americans Can No Longer Count on Treaties with the U.S. Government in 2 Historic U.S. Court Cases: An Encyclopedia 700, 701 (John W. Johnson ed. 2001).

- ↑ La Vere, at 194; Waldman, at 75.

- ↑ Treaty with the Kiowa, etc. of 1837, May 26, 1837, 7 Stat. 533; Mooney, at 169-71; Wunder, at 701.

- ↑ 2 Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties 489-91 (Charles J. Kappler, ed., 1904); Wunder, at 701.

- ↑ Treaty with the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache of 1853, July 27, 1853, 10 Stat. 1013.

- ↑ Kappler, at 600.

- ↑ La Vere, at 197; Waldman, at 76.

- ↑ Waldman, at 76; Carrie J. Crouch, Brazos Indian Reservation, Handbook of Texas Online (Feb. 1, 2013); W. E. S. Dickerson, Comanche Indian Reservation, Handbook of Texas Online (Feb. 1, 2013).

- ↑ Frances Mayhugh Holden, Lambshead Before Interwoven: A Texas Range Chronicle, 1848-1878 85 (1982); La Vere, at 201; Rupert N. Richardson, Neighbors, Robert Simpson, Handbook of Texas Online (Feb. 1, 2013).

- ↑ Waldman, at 76.

- ↑ Treaty with the Comanche and Kiowa of 1865, Oct. 18, 1865, 14 Stat. 717.

- ↑ Mooney, at 179-80.

- ↑ Treaty with the Kiowa and Comanche of 1867, 15 Stat. 581; Riley, at 194; Kappler, at 977; Mooney, at 181-86; Wunder, at 701.

- ↑ Wunder, at 701.

- ↑ Mooney, at 185; Wunder, at 701; Riley, at 194-96.

- ↑ Kappler, at 980; Moody, at 186.

- ↑ Riley, at 197.

- ↑ Riley, at 199-202.

- ↑ Waldman, at 76-77.

- ↑ Waldman, at 133; Riley, at 199-202.

- ↑ Waldman, at 133-34; Riley, at 197.

- ↑ La Vere, at 217.

- ↑ La Vere, at 217.

- ↑ La Vere, at 217; Paul James Moore, Kiowa Changes: The Impact of Transatlantic Influences 91-95 (2007).

- ↑ Riley, at 202-05.

- ↑ Raymond Cross, Sovereign Bargains, Indian Takings, and the Preservation of Indian Country in the Twenty-First Century: Lift Your Weapons. Here is the One that Resists Intentions, 40 Ariz. L. Rev. 425, 462 (1998); Riley, at 202-05.

- ↑ Riley, at 202-05.

- ↑ Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553, 555 (1903); Cross, at 463; La Vere, at 219-20; Wunder, at 701; Riley, at 202-05.

- ↑ Wunder, at 701; Riley, at 202-05.

- ↑ Riley, at 202-05.

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 554; La Vere, at 220; Wunder, at 701; Riley, at 202-05.

- ↑ La Vere, at 220.

- ↑ La Vere, at 220; Moore, at 108-09; Wunder, at 701-02; Riley, at 205-07.

- ↑ Riley, at 205 (internal citations omitted).

- ↑ Cross, at 463; Riley, at 205-07.

- ↑ Cross, at 463; Riley, at 205-07.

- ↑ Cross, at 464; Moore, at 108-09; Wunder, at 701-02; Riley, at 205-07.

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 559-60; Moore, at 116; Riley, at 205-07.

- ↑ Moore, at 117; Riley, at 207.

- ↑ Wunder, at 701-02; Riley, at 207-08.

- ↑ Riley, at 207-08.

- ↑ Wunder, at 701-02; Riley, at 207.

- ↑ Moore, at 117-18; Wunder, at 701-02; Riley, at 208.

- ↑ Moore, at 118.

- ↑ Cross, at 443, 464.

- ↑ Riley, at 208-09.

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 557; Riley, at 211.

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 560; Riley, at 209.

- ↑ Riley, at 209.

- ↑ La Vere, at 220; Moore, at 118.

- ↑ United States v. Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886)

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 563; Wunder, at 702.

- ↑ Wunder, at 702; Reilly, at 216-17.

- ↑ Wunder, at 702; Reilly, at 216-17.

- ↑ Wunder, at 702; Reilly, at 216-17.

- ↑ Reilly, at 216-17.

- ↑ Wunder, at 702; Reilly, at 216-17.

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 564.

- ↑ Wunder, at 703; Reilly, at 217.

- ↑ Wunder, at 703.

- ↑ Reilly, at 217-19.

- ↑ Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832)

- ↑ Reilly, at 217-19.

- ↑ Reilly, at 221.

- ↑ Reilly, at 221.

- ↑ Cross, at 464-65.

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 565.

- ↑ Lone Wolf, 187 U.S. at 567 (citing Kagama, 118 U.S. at 383.).

- ↑ "United States Supreme Court LONE WOLF v. HITCHCOCK, (1903) No. 275". FindLaw.

- ↑ Cross, at 464-65.

- ↑ Cross, at 443.

- ↑ Cross, at 443.

- ↑ Judith V. Royster, The Legacy of Allotment, 27 Ariz. St. L.J. 1, 11-12 (1995).

- ↑ Natsu Taylor Saito, The Plenary Power Doctrine: Subverting Human Rights in the Name of Sovereignty, 51 Cath. U. L. Rev. 1115, 1133-34 (2002); Reilly, at 224.

- ↑ Royster, at 13; Saito, at 1133; Cross, at 446 n.108.

- ↑ Royster, at 16.

- ↑ Reilly, at 224.

- ↑ Shelby D. Green, Specific Relief for Ancient Deprivations of Property, 36 Akron L. Rev. 245, 272-73 (2003).

- ↑ Green, at 273-74.

- ↑ Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857).

- ↑ Reilly, at 226.

Further reading

- Clark, Blue (1994). Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock: Treaty Rights and Indian Law at the End of the Nineteenth Century. Law in the American West. 5. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1466-9.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903), FindLaw, Text of the opinion