Lois Betteridge

| Lois Etherington Betteridge | |

|---|---|

|

Lois Betteridge in July 2012 | |

| Born |

Lois Etherington 1928 Drummondville, Québec, Canada |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Alma mater |

Ontario College of Art University of Kansas Cranbrook Academy of Art |

| Known for | Silversmith, goldsmith, educator |

| Spouse(s) | Keith Betteridge |

| Awards |

Saidye Bronfman Award for Excellence in Fine Craft (1978) Member, Order of Canada (1997) Lifetime Achievement Award, Society of North American Goldsmiths (2010) John and Barbara Mather Award for Lifetime Achievement (2014) |

| Website |

www |

Lois Etherington Betteridge is a Canadian silversmith, goldsmith, designer and educator, and has been a major figure in the Canadian studio craft movement since its inception in the 1950s. Betteridge was one of a small number of women active in the Canadian movement at a time when the field was dominated by male artists and designers, many of whom had immigrated to Canada from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe. Betteridge is the first modern Canadian silversmith to attain international stature in the studio craft movement.[1]

In 1978, Betteridge became the second recipient of the annual Saidye Bronfman Award,[2] Canada’s foremost national award for fine craft. In 1997, she was made a Member of the Order of Canada,[3] the country’s highest civilian honour, bestowed for a lifetime of distinguished service to the community. In 2010, Lois Betteridge received the Lifetime Achievement Award[4] of the Society of North American Goldsmiths. These three honours reflect Betteridge’s significance in Canadian arts and culture, and in North American metal arts. Judith Nasby, Director of the Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, identifies Betteridge as “without doubt Canada’s most highly honored and most influential silversmith”.[5]:59

Over a six-decade career, Betteridge has taught and mentored several generations of Canadian metal artists, smiths and jewellers, including First Nations sculptor Mary Anne Barkhouse,[6] and fellow Bronfman Award winner Kye-Yeon Son.[7] She maintains a studio in Guelph, Ontario.

Early life and education

Lois Etherington Betteridge was born in 1928 in Drummondville, Québec, and raised in Hamilton, Ontario. She attended the Ontario College of Art, (now OCAD University) then transferred to the University of Kansas, from which she graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Art in 1951. Returning to Canada, she augmented her academic training with evening classes in chasing and repoussé at the Provincial Institute of Trades (now Ryerson University) in Toronto, Ontario. Between 1954 and 1956, she attended the Cranbrook Academy of Art and completed a Master of Fine Art degree.[1]

Career

Following the completion of her undergraduate degree, Betteridge returned to Canada and opened a small studio in Oakville, Ontario, funded by a gift of $500 from her father.[8] In 1953, Betteridge opened a studio-gallery in Toronto on the edge of the affluent Rosedale neighbourhood, which enabled her to make initial contacts with designers, architects, collectors and other sources of commission work.

In the early 1950s, there were few Canadians working in the metal arts and Betteridge had little success connecting with the nascent metal arts community. Rather than teaching, or working in the commercial jewellery or silverware industries—common strategies for young metal artists at the start of their careers—she focused on developing a network of clients for her custom-designed jewellery and domestic and liturgical hollowware. This individualistic approach continued to be a defining feature of her studio practice throughout the 1950s and 1960s.[9]:36

After completing her graduate degree, Betteridge returned to Canada once more, and for three years taught weaving, design and metal arts at the MacDonald Institute (now part of the University of Guelph).[1] Finding that full-time teaching distracted from her studio work, Betteridge resigned and began making plans to further her studies in England. In the period between resigning and completing her arrangements, however, she met and married Keith Betteridge, a young English post-graduate student at the Ontario Veterinary College (now also part of the University of Guelph). In 1961 they moved to England, where Betteridge balanced the care of a young family and the establishment of her studio practice, while her husband completed doctoral studies in veterinary medicine.[10]:5 She participated regularly in multi-media exhibitions at the Bear Lane Gallery in Oxford. As she had done in Toronto, Betteridge used the gallery as a platform from which to reach a growing number of custom design clients.[8]

Sterling silver, raised, chased, repousséed, fabricated. A golden quartz cabuchon is set into the handle of the stirrer.[11]

Sterling silver, raised and fabricated, brass and acrylic.[11]

Sterling silver and gold, raised, pierced and fabricated.[11]

Copper, raised, forged, fabricated and patinated.[11]

Sterling silver, raised, chased and repousséed.[11]

Betteridge and her family returned to Canada in 1967. In the midst of the year-long social and cultural celebration that marked the nation’s Centennial Year, she found that the Canadian craft movement had finally developed critical mass. Professionally trained metalsmiths were graduating from art schools and community colleges in appreciable numbers. Many were setting up jewellery studios; Betteridge took this as a cue to focus on larger-scale work, and by the mid-1970s, hollowware was the focus of her practice.[9]:37 As she sought to re-establish herself in Canada, Betteridge resisted the pathway toward teaching at one of the new craft schools, preferring to hold workshops and to lecture as her schedule permitted. In the 1970s, she also began to offer informal apprenticeships in her own studio.[12]

Throughout the 1970s, Betteridge’s work evolved, as she entered a self-described “art” phase characterized by more expansive, organic forms, highly textured surfaces and objects whose form embodied witty, overt expressions of function.[10]:9 Honey Pot and Stirrer, 1976, is an exemplar of this phase. The vessel combines features of both a wasp nest and a honeycomb, natural forms that Betteridge studied in detail as part of her design process. A tiny, chased and repousséed bee in the recessed lid, and a golden quartz cabochon set in the handle of the stirrer, make droll references to the vessel’s use.[10]:10

This more interpretive phase of Betteridge's work found its most public expression in the late 1970s in two significant exhibitions: “Métiers d’art/3”, which traveled to Canadian Cultural Centers throughout Europe in 1978-1979, and “Reflections in Gold and Silver”, a major cross-Canada exhibition occasioned by her receiving the 1978 Saidye Bronfman award.[1]

In the 1980s, Betteridge undertook a new series of vessels composed of spherical, columnar and conical forms, fabricated in silver sheet combined with brass, copper, plexiglass and rubber.[10]:12 The influence of Post-Modernism can be read in the juxtaposition of these formal geometric compositions with Betteridge’s characteristic wit, and in the mixing of precious metal with non-precious materials. For example, Mad Hatter’s Tea Party, 1988, is a teapot that combines a formal, globular body with base and handle elements of acrylic, silver and brass sheet. The exposed connections between the individual components of the teapot display the post-modernist and constructivist influences with which Betteridge experimented during this period.[9]:40

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Betteridge continued to explore the formal qualities of metal sheet and, continuing the departure from her modernist roots, sought to combine geometric and organic forms with increasingly exuberant decoration. Spice Shaker, 1985, embodies the sensuality of the Jewish Havdalah ritual with which the vessel is associated. Gold wire elements evoke the aroma of spices, rising from a simple form raised from silver sheet.[9]:39 Tangled Garden: A tip of the hat to J.E.H. Macdonald, 1988, pushes further the exploration of organic and geometric shapes. Inspired by a painting by Canadian artist J. E. H. MacDonald, the patinated copper surface and twined wire elements evoke the overgrown organic forms of Macdonald's The Tangled Garden while the geometric base of the vessel suggests an underlying order in the natural world.[9]:39–40

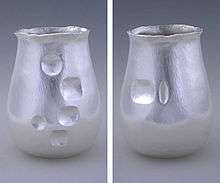

Beginning in the later 1990s, Betteridge returned to consider again the attractions of complex textures of her earlier work, using chasing and repoussé as both forming techniques and modes of surface embellishment.[10]:13 A later example of this phase of her work is the vessel Essence, 2007, which contrasts a fluid, organic form with the precise rendering of recessed, geometric shapes, the whole overlaid with a consistent hammered texture.

Influences and influence

Betteridge is the only Canadian metalsmith of her generation to receive extensive formal training in traditional silversmithing techniques at a university level.[10]:5 Her technical education reflected the European and American training of her teachers, including silversmith Hero Kielman, a Dutch immigrant to Canada; Carlyle H. Smith, whose metalsmithing program at Kansas was the first to be offered at an American university; and American silversmith Richard Thomas, who developed the first-full-time metal program at Cranbrook Academy of Arts. Betteridge’s time at Cranbrook shaped her aesthetic development, imbuing her work with the sculptural quality, clarity of form and technical proficiency that characterizes the American and Scandinavian schools of modernist design.[10]:6,7

The fundamental principles of Betteridge’s design philosophy have remained constant through six decades of practice: a modern unity of form and function wedded to traditional techniques. Over six decades of professional practice, Betteridge built a career as a studio silversmith that is literally unprecedented in its longevity, productivity and influence.[10]:13

Given her choice not to teach full-time, it is ironic that her greatest impact on Canadian metal arts may have been through teaching and mentoring. According to Ross Fox, curator of Canadian Decorative Arts at the Royal Ontario Museum (retired), it is “through her students that Lois has had the greatest impact on the craft, placing her at the very fulcrum of its national progress during the late twentieth century; there are few contemporary silversmiths in Canada who have not been under her tutelage”.[10]:6

Betteridge has taught and mentored numerous Canadian metal artists who have achieved prominence in their own right, including Beth Alber, Jackie Anderson, Anne Barros, Brigitte Clavette, Lois Frankel, Kye-Yeon Son and Ken Vickerson.[5]:59 In turn, these individuals have taught, lectured and served as senior faculty at post-secondary arts institutions in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario and Alberta.

Three significant exhibitions have celebrated her role as a mentor. In March 2000, work by Betteridge and six former students premiered appeared in "Tribute to Lois Betteridge", an exhibition at the Macdonald Stewart Arts Centre in Guelph, Ontario.[9]:40 In 2002, 38 of her former students mounted an exhibition called "Teacher, Silversmith, Mentor: 20 Years in the Highlands with Lois Etherington Betteridge" at the Haliburton School of the Arts in Haliburton, Ontario, where Betteridge taught summer programs between 1982 and 2002.[13] In 2008, Betteridge’s 80th birthday was observed with "Celebration", an exhibition at the Jonathon Bancroft Snell Gallery in London, ON that featured work by Betteridge and 20 former students – a “who’s who” of Canadian and First Nations silversmiths and metalsmiths.[10]:6

Awards

- 1955 Helen Scripps Booth Scholarship, Cranbrook Academy of Art

- 1974 Distinguished Member, Society of North American Goldsmiths

- 1975 Distinguished Professional Achievement, University of Kansas

- 1978 Member, Royal Canadian Academy of Arts

- 1978 Saidye Bronfman Award for Excellence in Crafts, Canada Council for the Arts

- 1988 Fellow, New Brunswick College of Craft and Design

- 1991 M. Joan Chalmers 15th Anniversary Award, Ontario Arts Council

- 1992 Honorary Fellow, Ontario College of Art [now OCAD University]

- 1997 Member, Order of Canada

- 2002 WM/WYCA Woman of Distinction Award for Lifetime Achievement

- 2002 Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal, Government of Canada

- 2010 Lifetime Achievement Award, Society of North American Goldsmiths

- 2012 Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal, Government of Canada

- 2014 John and Barbara Mather Award for Lifetime Achievement, Craft Ontario

Selected public collections and commissions

- Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, Scotland

- National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa, Ontario

- Canadian Museum of History, Bronfman Collection, Ottawa

- Ontario Crafts Council Permanent Collection, Toronto, Ontario

- Cranbrook Art Gallery, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, University of Guelph

- McLuhan Teleglobe Canada Awards, Montréal, Quebec

- President Constantine Karamanlis of Greece

- International Embryo Transfer Society, Champaign, Illinois

- Temple Israel, Ottawa

- Canadian Pacific Railway, Calgary, Alberta

- Massey Collection of Contemporary Crafts, Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec

- Holland College, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island

- Or Shalom Synagogue, London, Ontario

- Right Honourable Joseph Clark, Ottawa

- Canadian Nuclear Association, Ottawa

- Joan A. Chalmers National Craft Collection, Museum of Civilization, Gatineau

- Christ Church Cathedral, Vancouver, British Columbia

- Right Honourable Pierre Elliot Trudeau

- Marymount College, Sudbury, Ontario

- St. Christopher’s Anglican Church, Burlington, Ontario

Selected exhibitions

Lois Etherington Betteridge has participated in more than 120 exhibitions in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Belgium and Japan. These include:

- 1967 “Canadian Abstract Art - Centennial Exhibition”, Commonwealth Institute Gallery, London, UK

- 1977 “Contemporary Ontario Crafts”, Agnes Etherington Gallery, Kingston, ON

- 1981 “Reflections in Silver and Gold”, London Regional Art Gallery, London, ON; Alberta College of Art Gallery, Calgary, AB

- 1985-86 “Grand Prix des Metier dʼart”, Paris, Brussels, London

- 1988 “Masters of American Metalsmithing”, National Ornamental Metal Museum, Memphis, TN

- 1988 “Lois Etherington Betteridge, Silversmith: Recent Work”, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Hamilton, ON; Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Charlottetown PEI; Aitken Bicentennial Exhibition Centre, St. John, NB; Rails’ End Gallery, Haliburton, ON; Musée des Arts décoratifs de Montréal, Montreal, QC

- 1989 “Masters of the Crafts”, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, QC

- 1990 “Silver: New Forms and Expressions”, Schick Art Gallery, Saratoga Springs, NY

- 1995 “RCA Canadian Designers”, Budapest, Hungary; Burgundy, France, Edinburgh, Scotland

- 1996 “Transformations”, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, QC

- 1996 “Two for Tea”, Wellington County Museum, Guelph, ON

- 1997 “Precious Intentions”, Burlington Art Centre, Burlington, ON

- 1998 “Metal with Mettle”, Harbinger Centre, Waterloo, ON

- 1998 “Raised from Tradition: Holloware Past and Present”, Seafirst Gallery, Seattle, WA

- 1998 “Poetry of the Vessel” Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, NS

- 1999 “Benchmarkers: Women in Metal”, National Ornamental Metal Museum, Memphis, TN

- 1999 “Contemporary Images of Ontario”, Lieutenant-Governorʼs Suite, Queenʼs Park, Toronto, ON

- 2000 “Arts 2000”, Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts, Stratford, ON

- 2004-06 “In Service” Anna Leonowens Gallery, Halifax, NS; Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, Guelph, ON; Government House, Fredericton, NB; Object Design, Vancouver, BC; Illingworth Kerr Gallery, Calgary, AB; *New Gallery, Toronto, ON

- 1990-2005 “Beyond the Frame” annual exhibition, Macdonald Stewart Art Centre, Guelph, ON

- 2005 “Coffee for Four Friends” Design Exchange, Toronto, ON

- 2008-08 “Celebration” group exhibition, Jonathon Bancroft-Snell Gallery, London, ON

- 2012-13 “À Table!” group exhibition, Government House, Fredericton, NB; Anna Leonowens Gallery, Halifax, NS; Galerie Materia, Québec, QC; Design Exchange, Toronto, ON; University of Saskatchewan Art Gallery, Saskatoon, SK; MacDonald Stewart Art Centre, Guelph, ON

See also

- Ontario Crafts Council

- Royal Canadian Academy of Arts

- Order of Canada

- Society of North American Goldsmiths

References

- 1 2 3 4 Fox, Ross (1988). Lois Etherington Betteridge: Recent Work: Exhibition Catalogue. Art Gallery of Hamilton.

- ↑ "Saidye Bronfman Award - Prix Saidye-Bronfman". Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ "Governor General of Canada: Honours: Order of Canada". Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Barros, Anne. "2010 SNAG Lifetime Achievement Award, Lois Etherington Betteridge". Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- 1 2 Butt, Harlan W. (2010). "Lois Etherington Betteridge: Lifetime Achievement Award". Metalsmith. 30.5. Print.

- ↑ Dysart, Jennifer, Tanya Bob, in collaboration with Mary Anne Barkhouse. Old Punk Rockers Never Die, They Just Do Installation Art: A Profile of Artist Mary Anne Barkhouse. 2000. Vancouver: UBC Museum of Anthropology Pacific Northwest Sourcebook Series. 2012. Print.

- ↑ Hanrahan, Susan. “Kye-Yeon Son Nomination Statement”. Ottawa: Canada Council for the Arts, 2012. Print.

- 1 2 Betteridge, Lois (1978). "An Autobiography". Goldsmiths Journal. IV (2): 30. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Isherwood, Barbara (2000). "Moving Metal: Lois Etherington Betteridge". Metalsmith. 21 (2). Print.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Fox, Ross (2009). "Lois Etherington Betteridge, Pioneer of a Craft Revival in Canada". Silver Studies: the Journal of the Silver Society. 25. print

- 1 2 3 4 5 Betteridge, Lois Etherington. "Selected Works". Lois Etherington Betteridge. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Betteridge, Lois (1978). "An Autobiography". Goldsmiths Journal. IV (2): 31. Print.

- ↑ Barkhouse, Mary Anne; Nonferrous Collective; Barbara Isherwood (2002). Teacher, Silversmith, Mentor: Lois Etherington Betteridge. Missing or empty

|title=(help) Print.

External links

- Lois Betteridge - Silversmith and Goldsmith

- The Governor General of Canada: Honours

- Canada Council for the Arts: Prizes

- Canadian Museum of History: The Bronfman Collection Virtual Gallery

- Macdonald Stuart Art Centre: Silver Art Collection at MSAC

- Society of North American Goldsmiths