Liver injury

| Liver injury | |

|---|---|

| |

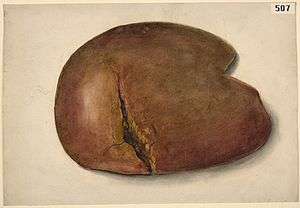

| Watercolour drawing of an extensive rupture of the liver | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | emergency medicine |

| ICD-10 | S36.119 |

| ICD-9-CM | 864 |

A liver injury, also known as liver laceration, is some form of trauma sustained to the liver. This can occur through either a blunt force such as a car accident, or a penetrating foreign object such as a knife [1] Liver injuries constitute 5% of all traumas, making it the most common abdominal injury.[2] Generally nonoperative management and observation is all that is required for a full recovery.

Cause

Given its anterior position in the abdominal cavity and its large size, it is prone to gun shot wounds and stab wounds.[2] Its firm location under the diaphragm also makes it especially prone to shearing forces.[1] Common causes of this type of injury are blunt force mechanisms such as motor vehicle accidents, falls, and sports injuries. Typically these blunt forces dissipate through and around the structure of the liver.[3] A large majority of people who sustain this injury also have another accompanying injury.[1]

Diagnosis

Imaging, such as the use of ultrasound or a computed tomography scan, is the generally preferred way of diagnosis as it is more accurate and is sensitive to bleeding, however; due to logistics this is not always possible.[4] For a person who is hemodynamically unstable a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) scan may take place which is used to find free floating fluid in the right upper quadrant and left lower quadrant of the abdomen. A physical examination may be used but is typically inaccurate in blunt trauma, unlike in penetrating trauma where the trajectory the projectile took can be followed digitally.[5] A diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) may also be utilized but has limited application as it is hard to determine the origin of the bleeding.[6]

Classification

| Grade | Subcapsular hematoma | Laceration |

|---|---|---|

| I | <10% surface area | < 1 cm in depth |

| II | 10–50% surface area | 1–3 cm |

| III | >50% or >10 cm | >3 cm |

| IV | 25–75% of a hepatic lobe | |

| V | >75% of a hepatic lobe | |

| VI | Hepatic avulsion |

Liver injuries are classified on a Roman numeral scale with I being the least severe, to VI being the most severe. Generally any injury ≥III requires surgery.[3][7]

Management

The initial management of liver trauma generally follows the same procedures for all traumas with a focus on maintaining airway, breathing, and circulation. A physical examination is a corner stone of the assessment of which there are various non-invasive means of diagnostic tools that can be utilized.[3] An invasive diagnostic peritoneal lavage can also be used to diagnose and classify the extent of the damage.[8][9] A large majority of liver injuries are minor and require only observation.[10] Generally if there is estimated to be less than 300mL of free floating fluid, no injury to surrounding organs, and no need for blood transfusion, there is a low risk of complication from nonoperative management.[1] In special cases where there is a higher risk with surgery, such as in the elderly, nonoperative management would include the infusion of packed red blood cells in an intensive care unit.[2] Typically hepatic injuries resulting from stab wounds cause little damage unless a vital part of the liver is injured such as the hepatic portal vein, with gunshot wounds, the damage is worse.[11]

Surgery

In severe liver injuries (class ≥III), surgical correction is generally necessary. In these severe injuries a hepatopancreatobiliary surgeon may be utilized rather than a trauma surgeon given their expertise with the organ and generally yields better outcomes.[1] Surgical techniques such as perihepatic packing or the use of the Pringle manoeuvre can be used to control hemorrhage.[2][3] Temporary control of the hemorrhage can be direct manual pressure to the wound site.[2] In these severe cases it is important to prevent the progression of the trauma triad of death, which often requires the utilization of damage control surgery.[9] The common cause of death while operating is exsanguination caused by profuse loss of blood volume.[12] Rarely, surgery entails the use of liver resection, which removes the source of the bleeding and necrotic tissue. The drastic nature of this procedure means it can only be used in hemodynamically stable patients.[7] Another rare procedure would be liver transplantation which is typically impractical due to the logistics of finding a proper organ donor in a timely fashion.[13]

kous netzoff aluminium needle is used to suture liver tear. Co-opting sutures are placed perpendicular to already placed parallel mattress sutures on either side of lacerations. Other methods are tractotomy and mesh hepatorrhaphy.

History

In the 1880s a severe liver injury would in most cases prove fatal in the first 24 hours after sustaining the injury.[14] Before the 1980s nonoperative management was seldom used in favor of the methods of management suggested by James Hogarth Pringle.[15][16] During World War II the use of early laparotomy was popularized and in conjunction with the use of transfusions, advanced anesthetics, and other new surgical techniques led to decreased mortality.[17]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Piper GL, Peitzman AB (August 2010). "Current management of hepatic trauma". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 90 (4): 775–85. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2010.04.009. PMID 20637947. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cothren, C. C.; Moore, E. E. (2008). "Hepatic Trauma". European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 34 (4): 339. doi:10.1007/s00068-008-8029-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Bouras AF, Truant S, Pruvot FR (December 2010). "Management of blunt hepatic trauma". Journal of Visceral Surgery. 147 (6): e351–8. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.10.004. PMID 21111696. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ↑ Moore 2012, p. 543

- ↑ Pietzman 2002, p. 255

- ↑ Moore 2012, p. 542

- 1 2 Arkuszewski, P.; Krawczyk, M. (2009). "Surgical Management of Liver Trauma". Polish Journal of Surgery. 81 (11): 554. doi:10.2478/v10035-009-0090-1.

- ↑ Moore 2012, p. 541

- 1 2 Stracieri LD, Scarpelini S (2006). "Hepatic injury". Acta Cirurgica Brasileira. 21 Suppl 1: 85–8. doi:10.1590/s0102-86502006000700019. PMID 17013521. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ↑ American College of Surgeons (2004). Atls, Advanced Trauma Life Support Program for Doctors. Amer College of Surgeons. ISBN 1-880696-14-2.

- ↑ Kenneth D. Boffard (2007). Manual of definitive surgical trauma care. London: Hodder Arnold. p. 108. ISBN 0-340-94764-0.

- ↑ Ahmed, I.; Beckingham, I. (2007). "Liver trauma". Trauma. 9 (3): 171. doi:10.1177/1460408607086775.

- ↑ Parks RW, Chrysos E, Diamond T (September 1999). "Management of liver trauma". The British Journal of Surgery. 86 (9): 1121–35. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01210.x. PMID 10504364. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- ↑ Moynihan, Baron Berkeley (1906). Abdominal operations. Saunders. p. 563. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- ↑ Pringle JH (October 1908). "V. Notes on the Arrest of Hepatic Hemorrhage Due to Trauma". Annals of Surgery. 48 (4): 541–9. doi:10.1097/00000658-190810000-00005. PMC 1406963

. PMID 17862242. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

. PMID 17862242. Retrieved 2012-08-03. - ↑ Moore 2012, p. 539

Bibliography

- Feliciano, David V.; Mattox, Kenneth L.; Moore, Ernest J (2012). Trauma, Seventh Edition (Trauma (Moore)). McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-166351-7.

- Andrew B., MD Peitzman; Andrew B. Peitzman; Michael, MD Sabom; Donald M., MD Yearly; Timothy C., MD Fabian (2002). The trauma manual. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-2641-7.