Little Rock Nine

| Little Rock Nine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

|

The "Little Rock Nine" are escorted inside Little Rock Central High School by troops of the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army. | |||

| Location | Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas | ||

| Causes | |||

| Result |

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| ||

|---|---|---|

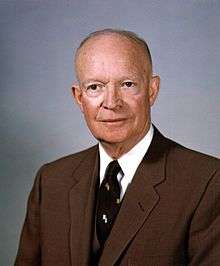

President of the United States First Term Second Term Post-Presidency |

||

The Little Rock Nine was a group of nine African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Their enrollment was followed by the Little Rock Crisis, in which the students were initially prevented from entering the racially segregated school by Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas. They then attended after the intervention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The U.S. Supreme Court issued its historic Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 347 U.S. 483, on May 17, 1954. Tied to the 14th Amendment, the decision declared all laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional, and it called for the desegregation of all schools throughout the nation.[1] After the decision, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) attempted to register black students in previously all-white schools in cities throughout the South. In Little Rock, the capital city of Arkansas, the Little Rock School Board agreed to comply with the high court's ruling. Virgil Blossom, the Superintendent of Schools, submitted a plan of gradual integration to the school board on May 24, 1955, which the board unanimously approved. The plan would be implemented during the fall of the 1957 school year, which would begin in September 1957.

By 1957, the NAACP had registered nine black students to attend the previously all-white Little Rock Central High, selected on the criteria of excellent grades and attendance.[2] Called the "Little Rock Nine", they were Ernest Green (b. 1941), Elizabeth Eckford (b. 1941), Jefferson Thomas (1942–2010), Terrence Roberts (b. 1941), Carlotta Walls LaNier (b. 1942), Minnijean Brown (b. 1941), Gloria Ray Karlmark (b. 1942), Thelma Mothershed (b. 1940), and Melba Pattillo Beals (b. 1941). Ernest Green was the first African American to graduate from Central High School.

The Blossom Plan

One of the plans created during attempts to desegregate the schools of Little Rock was by school superintendent Virgil Blossom. The initial approach proposed substantial integration beginning quickly and extending to all grades within a matter of many years.[3] This original proposal was scrapped and replaced with one that more closely met a set of minimum standards worked out in attorney Richard B. McCulloch's brief.[4] This finalized plan would start in September 1957 and would integrate one high school, Little Rock Central. The second phase of the plan would take place in 1960 and would open up a few junior high schools to a few black children. The final stage would involve limited desegregation of the city's grade schools at an unspecified time, possibly as late as 1963.[4]

This plan was met with varied reactions from the NAACP branch of Little Rock. Militant members like the Bateses opposed the plan on the grounds that it was "vague, indefinite, slow-moving and indicative of an intent to stall further on public integration."[5] Despite this view, the majority accepted the plan; most felt that Blossom and the school board should have the chance to prove themselves, that the plan was reasonable, and that the white community would accept it.

This view was short lived, however. Changes were made to the plan, the most detrimental being a new transfer system that would allow students to move out of the attendance zone to which they were assigned.[5] The unaltered Blossom Plan had gerrymandered school districts to guarantee a black majority at Horace Mann High and a white majority at Hall High.[5] This meant that, even though black students lived closer to Central, they would be placed in Horace Mann thus confirming the intention of the school board to limit the impact of desegregation.[5] The altered plan gave white students the choice of not attending Horace Mann, but didn't give black students the option of attending Hall. This new Blossom Plan did not sit well with the NAACP and after failed negotiations with the school board; the NAACP filed a lawsuit on February 8, 1956.

This lawsuit, along with a number of other factors contributed to the Little Rock School Crisis of 1957.

National Guard blockade

Several segregationist councils threatened to hold protests at Central High and physically block the black students from entering the school. Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to support the segregationists on September 4, 1957. The sight of a line of soldiers blocking out the students made national headlines and polarized the nation. Regarding the accompanying crowd, one of the nine students, Elizabeth Eckford, recalled:

They moved closer and closer. ... Somebody started yelling. ... I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the crowd—someone who maybe could help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me.[6]

On September 9, the Little Rock School District issued a statement condemning the governor's deployment of soldiers to the school, and called for a citywide prayer service on September 12. Even President Dwight Eisenhower attempted to de-escalate the situation by summoning Faubus for a meeting, warning him not to defy the Supreme Court's ruling.[7]

Armed escort

Woodrow Wilson Mann, the mayor of Little Rock, asked President Eisenhower to send federal troops to enforce integration and protect the nine students. On September 24, the President ordered the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army—without its black soldiers, who rejoined the division a month later—to Little Rock and federalized the entire 10,000-member Arkansas National Guard, taking it out of the hands of Faubus.[8]

A tense year

By the end of September 1957, the nine were admitted to Little Rock Central High under the protection of the 101st Airborne Division (and later the Arkansas National Guard), but they were still subjected to a year of physical and verbal abuse (being spat on and called names) by many of the white students. Melba Pattillo had acid thrown into her eyes[9] and also recalled in her book, Warriors Don't Cry, an incident in which a group of white girls trapped her in a stall in the girls' washroom and attempted to burn her by dropping pieces of flaming paper on her from above. Another one of the students, Minnijean Brown, was verbally confronted and abused. She said

I was one of the kids 'approved' by the school officials. We were told we would have to take a lot and were warned not to fight back if anything happened. One girl ran up to me and said, 'I'm so glad you're here. Won't you go to lunch with me today?' I never saw her again.[10]

Minnijean Brown was also taunted by members of a group of white male students in December 1957 in the school cafeteria during lunch. She dropped her lunch, a bowl of chili, onto the boys and was suspended for six days. Two months later, after more confrontation, Brown was suspended for the rest of the school year. She transferred to New Lincoln High School in New York City.[2] As depicted in the 1981 made-for-TV docudrama Crisis at Central High, and as mentioned by Melba Pattillo Beals in Warriors Don't Cry, white students were punished only when their offense was "both egregious and witnessed by an adult".[11] The drama was based on a book by Elizabeth Huckaby, a vice-principal during the crisis.

"The Lost Year"

In the summer of 1958, as the school year was drawing to a close, Faubus decided to petition the decision by the Federal District Court in order to postpone the desegregation of public high schools in Little Rock.[12] In the Cooper v. Aaron case, the Little Rock School District, under the leadership of Orval Faubus, fought for a two and a half year delay on de-segregation, which would have meant that black students would only be permitted into public high schools in January 1961.[13] Faubus argued that if the schools remained integrated there would be an increase in violence. However, in August 1958, the Federal Courts ruled against the delay of de-segregation, which incited Faubus to call together an Extraordinary Session of the State Legislature on August 26 in order to enact his segregation bills.[14]

Claiming that Little Rock had to assert their rights and freedom against the federal decision, in September 1958, Faubus signed acts that enabled him and the Little Rock School District to close all public schools.[15] Thus, with this bill signed, on Monday September 15, Faubus ordered the closure of all four public high schools, preventing both black and white students from attending school.[16] Despite Faubus's decree, the town's population had the chance of refuting the bill since the school-closing law necessitated a referendum. The referendum, which would either condone or condemn Faubus's law, was to take place within thirty days.[16] A week before the referendum, which was scheduled to take place on September 27, Faubus addressed the citizens of Little Rock in an attempt to secure their votes. Faubus urged the population to vote against integration since he was planning on leasing the public school buildings to private schools, and, in doing so, would educate the white and black students separately.[17] Faubus was successful in his appeal and won the referendum. This year came to be known as the "Lost Year."

Faubus's victory led to a series of consequences that affected Little Rock society. Faubus's intention to open private schools was denied the same day the referendum took place, which caused some citizens of Little Rock to turn on the black community. The black community became a target for hate crimes since people blamed them for the closing of the schools.[18] Daisy Bates, head of the NAACP chapter in Little Rock, was a primary victim to these crimes, in addition to the black students enrolled at Little Rock Central High School and their families.[19]

The town's teachers were also placed in a difficult position. They were forced to swear loyalty to Faubus's bills.[16] Even though Faubus's idea of private schools never played out, the teachers were still expected to attend school every day and prepare for the possibility of their students' return.[20] The teachers were completely under Faubus's control and the many months that the school stayed empty only served as a cause for uncertainty in their professional futures.[21]

In May 1959, after the firing of forty-four teachers and administrative staff from the four high schools, three segregationist board members were replaced with three moderate ones. The new board members reinstated the forty-four staff members to their positions.[22] The new board of directors then began an attempt to reopen the schools, much to Faubus's dismay. In order to avoid any further complications, the public high schools were scheduled to open earlier than usual, on August 12, 1959.[22]

Although the Lost Year had come to a close, the black students who returned to the high schools were not welcomed by the other students. Rather, the black students had a difficult time getting past mobs to enter the school, and, once inside, they were often subject to physical and emotional abuse.[23] The students were back at school and everything would eventually resume normal function, but the Lost Year would be a pretext for new hatred towards the black students in the public high school.

Motivations

Faubus's opposition to desegregation was likely both politically and racially motivated.[24] Although Faubus had indicated that he would consider bringing Arkansas into compliance with the high court's decision in 1956, desegregation was opposed by his own southern Democratic Party, which dominated all Southern politics at the time. Faubus risked losing political support in the upcoming 1958 Democratic gubernatorial primary if he showed support for integration.[25]

Most histories of the crisis conclude that Faubus, facing pressure as he campaigned for a third term, decided to appease racist elements in the state by calling out the National Guard to prevent the black students from entering Central High. Former associate justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court James D. Johnson claimed to have hoaxed Governor Faubus into calling out the National Guard, supposedly to prevent a white mob from stopping the integration of Little Rock Central High School: "There wasn't any caravan. But we made Orval believe it. We said. 'They're lining up. They're coming in droves.' ... The only weapon we had was to leave the impression that the sky was going to fall." He later claimed that Faubus asked him to raise a mob to justify his actions.[26]

Harry Ashmore, the editor of the Arkansas Gazette, won a 1958 Pulitzer Prize for his editorials on the crisis. Ashmore portrayed the fight over Central High as a crisis manufactured by Faubus; in his interpretation, Faubus used the Arkansas National Guard to keep black children out of Central High School because he was frustrated by the success his political opponents were having in using segregationist rhetoric to stir white voters.[27]

Congressman Brooks Hays, who tried to mediate between the federal government and Faubus, was later defeated by a last minute write-in candidate, Dale Alford, a member of the Little Rock School Board who had the backing of Faubus's allies.[28] A few years later, despite the incident with the "Little Rock Nine", Faubus ran as a moderate segregationist against Dale Alford, who was challenging Faubus for the Democratic nomination for governor in 1962.

Legacy

Little Rock Central High School still functions as part of the Little Rock School District, and is now a National Historic Site that houses a Civil Rights Museum, administered in partnership with the National Park Service, to commemorate the events of 1957.[29] The Daisy Bates House, home to Daisy Bates, then the president of the Arkansas NAACP and a focal point for the students, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2001 for its role in the episode.[30]

In 1958, Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén published "Little Rock", a bilingual composition in English and Spanish denouncing the racial segregation in the United States.[31]

Melba Pattillo Beals wrote a memoir titled Warriors Don't Cry, published in the mid-1990s.

Two made-for-television movies have depicted the events of the crisis: the 1981 CBS movie Crisis at Central High, and the 1993 Disney Channel movie The Ernest Green Story.

In 1996, seven of the Little Rock Nine appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show. They came face to face with a few of the white students who had tormented them as well as one student who had befriended them.

President Bill Clinton honored the Little Rock Nine in November 1999 when he presented them each with a Congressional Gold Medal. The medal is the highest civilian award bestowed by Congress.[32] It is given to those who have provided outstanding service to the country. To receive the Congressional Gold Medal, recipients must be co-sponsored by two-thirds of both the House and Senate.

In 2007, the United States Mint made available a commemorative silver dollar to "recognize and pay tribute to the strength, the determination and the courage displayed by African-American high school students in the fall of 1957." The obverse depicts students accompanied by a soldier, with nine stars symbolizing the Little Rock Nine. The reverse depicts an image of Little Rock Central High School, c. 1957. Proceeds from the coin sales are to be used to improve the National Historic Site.

On December 9, 2008, the Little Rock Nine were invited to attend the inauguration of President-elect Barack Obama, the first African-American to be elected President of the United States.[33]

On February 9, 2010, Marquette University honored the group by presenting them with the Père Marquette Discovery Award, the university's highest honor, one that had previously been given to Mother Teresa, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Karl Rahner, and the Apollo 11 astronauts, among other notables.

See also

- Black school

- Stand in the Schoolhouse Door

- Little Rock (poem)

- Nine from Little Rock, an Academy Award winning documentary film about the Little Rock Nine

- Fables of Faubus, a song written by jazz bassist Charles Mingus

Footnotes

- ↑ Brown v. Topeka Board of Education (U.S. 1954). Text.

- 1 2 Rains, Craig. "Little Rock Central High 40th Anniversary"..

- ↑ Tony A. Freyer, "Politics and Law in the Little Rock Crisis, 1954–1957," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 60/2, (Summer 2007): 148

- 1 2 Tony A. Freyer, "Politics and Law in the Little Rock Crisis, 1954–1957," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 60/2, (Summer 2007): 149

- 1 2 3 4 John A. Kirk, "The Little Rock Crisis and Postwar Black Activism in Arkansas," The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 60/2, (Summer 2007): 239

- ↑ Boyd, Herb (September 27, 2007). "Little Rock Nine paved the way". New York Amsterdam News. 98 (40). Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ↑ "Retreat from Newport". Time. September 23, 1957..

- ↑ Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. Random House. p. 723. ISBN 978-0-679-64429-3.

- ↑ "Melba Pattillo Beals". Teachers' Domain. WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ↑ Brown, Minnijean; Moskin, J. Robert (June 24, 1958). "One Girl's Little Rock Story". Look.

- ↑ Collins, Janelle (Fall 2008). "Easing a Country's Conscience: Little Rock's Central High School in Film". The Southern Quarterly. The University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir. New York: David McKay, 1962, p. 151.

- ↑ Gordy, Sondra. "Empty Hearts: Little Rock Secondary Teachers, 1958–1959". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 1997, p. 428.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir. New York: David McKay, 1962, p. 152.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir. New York: David McKay, 1962, p. 154.

- 1 2 3 Gordy, Sondra. "Empty Hearts: Little Rock Secondary Teachers, 1958–1959". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 1997, p. 429.

- ↑ Gordy, Sondra. "Empty Hearts: Little Rock Secondary Teachers, 1958–1959". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 1997, p. 431.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir. New York: David McKay, 1962, p. 155.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir. New York: David McKay, 1962. p. 159.

- ↑ Gordy, Sondra. "Empty Hearts: Little Rock Secondary Teachers, 1958–1959". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 1997, p. 436.

- ↑ Gordy, Sondra. "Empty Hearts: Little Rock Secondary Teachers, 1958–1959". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 1997, p. 441.

- 1 2 Gordy, Sondra. "Empty Hearts: Little Rock Secondary Teachers, 1958–1959". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, 1997, p. 442.

- ↑ Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock: A Memoir. New York: David McKay, 1962, p. 165.

- ↑ "Little Rock Nine". Originalpeople. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ Williams, Juan (March 18, 2007). "Showdown over Segregation". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ "Racist "Justice" is dead, but not gone". Salon. February 18, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ "The Pulitzer Prize Winners 1958". the Pulitzer Board. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ Profiles in Hue. Xlibris Corporation. p. 366. ISBN 1456851209. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ United States National Park Service, Little Rock Central High School, National Historic Site.

- ↑ "NHL nomination for Daisy Bates House" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-10-27.

- ↑ Guillén, Nicolás; Márquez, Robert; McMurray, David Arthur (August 2003). Man-making words: selected poems of Nicolás Guillén. Univ of Massachusetts Press. pp. 58–61. ISBN 978-1-55849-410-7. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "Little Rock Nine". November 9, 1999. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ↑ "We've Completed Our Mission". Washington Post, December 13, 2009, p. B01.

References

- Anderson, Karen. Little Rock: Race and Resistance at Central High School (2013)

- Baer, Frances Lisa. Resistance to Public School Desegregation: Little Rock, Arkansas, and Beyond (2008) 328 pp. ISBN 978-1-59332-260-1

- Beals, Melba Pattillo. Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High. (ISBN 0-671-86638-9)

- Branton, Wiley A. "Little Rock Revisited: Desegregation to Resegregation." Journal of Negro Education 1983 52(3): 250–269. ISSN 0022-2984 Fulltext in Jstor

- Jacoway, Elizabeth. Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis That Shocked the Nation (2007).

- Kirk, John A. "Not Quite Black and White: School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954-1966," Arkansas Historical Quarterly (2011) 70#3 pp 225–257 in JSTOR

- Kirk, John A., ed. An Epitaph for Little Rock: A Fiftieth Anniversary Retrospective on the Central High Crisis (University of Arkansas Press, 2008).

- Kirk, John A. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis (University of Arkansas Press, 2007).

- Kirk, John A., Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970 (University of Florida Press, 2002).

- Reed, Roy. Faubus: The Life and Times of an American Prodigal (1997).

- Lanier, Carlotta, A Mighty Long Way: My Journey to Justice at Little Rock Central High School, Random House, 2009

Historiography

- Pierce, Michael. "Historians of the Central High Crisis and Little Rock's Working-Class Whites: A Review Essay," Arkansas Historical Quarterly (2011) 70#4 pp. 468–483 in JSTOR

Primary sources

- Faubus, Orval Eugene. Down from the Hills. Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithographing, 1980. 510 pp. autobiography.

External links

- "Through a Lens, Darkly," by David Margolick. Vanity Fair, September 24, 2007.

- The Tiger, Student Paper of Little Rock Central High.

- The Legacy of Little Rock on Time.com (a division of Time Magazine)

- Guardians of Freedom—50th Anniversary of Operation Arkansas, by United States Army

- Letters from U.S. citizens regarding the Little Rock Crisis, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Documents regarding the Little Rock Crisis, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- National Park Service. Little Rock Central High School, National Historic Site.

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture entry: Little Rock Nine

- "From Canterbury to Little Rock: The Struggle for Educational Equality for African Americans", a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Interview with Melba Pattillo Beals about her book Warriors Don't Cry: A Searing Memoir of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock's Central High, Booknotes, November 27, 1994.

- Letter by segregationist lawyer Amis Guthridge Defending Segregation to Little Rock School Board and Superintendent Blossom, July 10, 1957.

- McMillen, Neil R. (Summer 1971). "White Citizens' Council and Resistance to School Desegregation in Arkansas" (PDF). The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 30 (2): 95–122.

- Sandra Hubbard; Dr. Sondra Gordy. "The Lost Year". a documentary, entitled "The Lost Year" by Sandra Hubbard and a book, entitled "Finding the Lost Year" By Dr. Gordy. An account by teachers and classmates of the closed high schools of Little Rock after the Crisis at Central High and the Little Rock Nine.