List of Presidents of the Philippines

.jpg)

Under the Constitution of the Philippines, the President of the Philippines (Filipino: Pangulo ng Pilipinas) is both the head of state and the head of government, and also serves as the commander-in-chief of the country's armed forces.[4] The President is directly elected by qualified voters of the population to a six-year term and must be "a natural-born citizen of the Philippines, a registered voter, able to read and write, at least forty years of age on the day of the election, and a resident of the Philippines for at least ten years immediately preceding such election". Any person who has served as president for more than four years is barred from running for the position again. Upon an incumbent president's death, permanent disability, resignation, or removal from office, the Vice President assumes the post.[5]

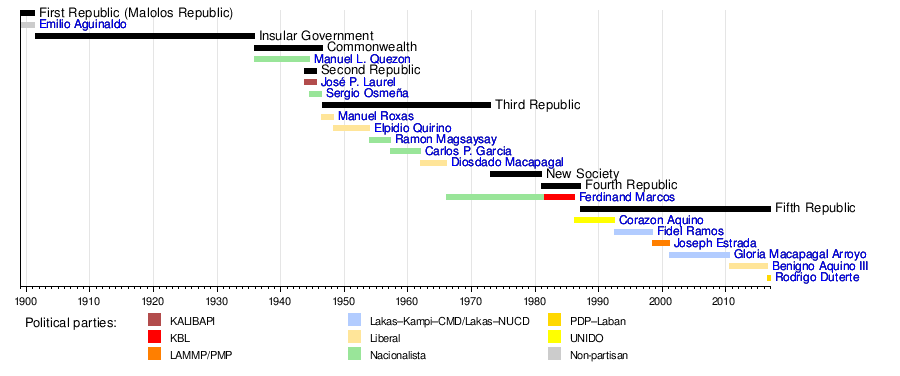

Sixteen people have been sworn into office as president. Following the ratification of the Malolos Constitution in 1899, Emilio Aguinaldo became the inaugural president of the Malolos Republic, considered the First Philippine Republic.[6][note 2] He held that office until 1901 when he was captured by United States forces during the Philippine–American War (1899–1902).[4] The American colonization of the Philippines abolished the First Republic,[7] which led an American governor-general to exercise executive power.[8]

In 1935 the US, pursuant to its promise of full Philippine sovereignty,[9] established the Commonwealth of the Philippines following the ratification of the 1935 Constitution, which also restored the presidency. The first national presidential election was held,[note 3] and Manuel L. Quezon (1935–44) was elected to a six-year term, with no provision for re-election,[12] as the second Philippine president and the first Commonwealth president.[note 2] In 1940, however, the Constitution was amended to allow re-election but shortened the term to four years.[4] A change in government occurred three years later when the Second Philippine Republic was organized with the enactment of the 1943 Constitution, which Japan imposed after it occupied the Philippines in 1942 during World War II.[13] José P. Laurel acted as puppet president of the new Japanese-sponsored government;[14] his de facto presidency,[15] not legally recognized until the 1960s,[16] overlapped with that of the president of the Commonwealth, which went into exile. The Second Republic was dissolved after Japan surrendered to the Allies in 1945; the Commonwealth was restored in the Philippines in the same year with Sergio Osmeña (1944–46) as president.[4]

Manuel Roxas (1946–48) followed Osmeña when he won the first post-war election in 1946. He became the first president of the independent Philippines when the Commonwealth ended on July 4 of that year. The Third Republic was ushered in and would cover the administrations of the next five presidents, the last of which was Ferdinand Marcos (1965–86),[4] who performed a self-coup by imposing martial law in 1972.[17] The dictatorship saw the birth of Marcos' New Society and the Fourth Republic. His tenure lasted until 1986 when he was deposed in the People Power Revolution. The current constitution came into effect in 1987, marking the beginning of the Fifth Republic.[4]

Of the individuals elected as president, three died in office: two of natural causes (Manuel L. Quezon[18] and Manuel Roxas[19]) and one in a plane crash (Ramon Magsaysay (1953–57)[20]). The longest-serving president is Ferdinand Marcos with 20 years and 57 days in office; he is the only president to have served more than two terms. The shortest is Sergio Osmeña who spent 1 year and 300 days in office; he is the first Philippine vice president as well as the first to succeed to the presidency (upon the death of Quezon). The first female president of the Philippines (and of any Asian country[21]) is Corazon Aquino (1986–92). Rodrigo Duterte is the incumbent president since 2016.

Key

The colors indicate the political party affiliation of each individual.

| Party | English name | Abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kapisanan ng Paglilingkod sa Bagong Pilipinas | Association for Service to the New Philippines | KALIBAPI | |

| Kilusang Bagong Lipunan | New Society Movement | KBL | |

| Laban ng Makabayang Masang Pilipino | Struggle of the Patriotic Filipino Masses | LAMMP | |

| Lakas ng Tao–Kabalikat ng Malayang Pilipino–Christian Muslim Democrats | People Power–Partner of the Free Filipino–Christian Muslim Democrats | Lakas–Kampi–CMD | |

| Lakas ng Tao–National Union of Christian Democrats | People Power–National Union of Christian Democrats | Lakas–NUCD | |

| Liberal Party | Liberal | ||

| Nacionalista Party | Nationalist Party | Nacionalista | |

| Nationalist People's Coalition | NPC | ||

| Partido Demokratiko Pilipino–Lakas ng Bayan | Philippine Democratic Party–People's Power | PDP–Laban | |

| United Nationalist Democratic Organization | UNIDO | ||

| Non-partisan | N/A | ||

Presidents

1899–1901: First Republic (Malolos Republic)

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 4] Upon the death of fifth president, Manuel Roxas, Elpidio Quirino became the sixth president even though he simply served out the remainder of Roxas' term and was not elected to the presidency in his own right.</ref> |

Vice President | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |  |

Emilio Aguinaldo (1869–1964) |

January 23, 1899 [note 5] |

March 23, 1901 [note 6]</ref> [note 7]</ref> |

Non-partisan | 1 (1899) |

None [note 8] |

[10] [11] | |

1935–46: Commonwealth

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 4] |

Vice President | Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 |  |

Manuel L. Quezon (1878–1944) |

November 15, 1935 [note 9] |

August 1, 1944 [note 10] [note 11] |

Nacionalista | 2 (1935) |

Sergio Osmeña | [36] [37] [38] [12] | ||

| 3 (1941) | |||||||||||

| 4 [note 12] |

2 |  |

Sergio Osmeña (1878–1961) |

August 1, 1944 | May 28, 1946 [note 13] [note 14] |

Nacionalista | Vacant [note 15] |

[39] [40] [12] | |||

| 5 | 3 |  |

Manuel Roxas (1892–1948) |

May 28, 1946 | April 15, 1948 [note 16] |

Liberal [note 17] |

5 [note 12] (1946) |

Elpidio Quirino May 28, 1946 – April 17, 1948 |

[43] [44] [41] | ||

1943–45: Second Republic

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 4] |

Vice President | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 |  |

José P. Laurel (1891–1959) |

October 14, 1943 [note 18] |

August 17, 1945 [note 19]</ref> [note 7] |

KALIBAPI [note 20] |

4 (1943) |

None [note 21] |

[47] [50] | |

1946–73: Third Republic

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 4] |

Vice President | Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1 |  |

Manuel Roxas (1892–1948) |

May 28, 1946 | April 15, 1948 [note 16] |

Liberal [note 17] |

5 (1946) |

Elpidio Quirino May 28, 1946 – April 17, 1948 |

[43] [44] [41] | ||

| Vacant April 15–17, 1948 |

[52] | ||||||||||

| 6 | 2 |  |

Elpidio Quirino (1890–1956) |

April 17, 1948 | December 30, 1953 [note 13] |

Liberal [note 23] |

Vacant [note 15] April 17, 1948 – December 30, 1949 |

[54] [55] [41] [53] | |||

| 6 (1949) |

Fernando Lopez December 30, 1949 – December 30, 1953 | ||||||||||

| 7 | 3 |  |

Ramon Magsaysay (1907–1957) |

December 30, 1953 | March 17, 1957 [note 24] |

Nacionalista | 7 (1953) |

Carlos P. Garcia | [57] [58] [59] | ||

| 8 | 4 |  |

Carlos P. Garcia (1896–1971) |

March 18, 1957 | December 30, 1961 [note 13] |

Nacionalista | Vacant [note 15] March 18 – December 30, 1957 |

[60] [61] [59] [62] | |||

| 8 (1957) |

Diosdado Macapagal December 30, 1957 – December 30, 1961 | ||||||||||

| 9 | 5 |  |

Diosdado Macapagal (1910–1997) |

December 30, 1961 | December 30, 1965 [note 13] |

Liberal | 9 (1961) |

Emmanuel Pelaez | [63] [64] [65] | ||

| 10 | 6 |  |

Ferdinand Marcos (1917–1989) |

December 30, 1965 | February 25, 1986 [note 13] [note 25] |

Nacionalista | 10 (1965) |

Fernando Lopez December 30, 1965 – September 23, 1972 [note 26] |

[71] [72] [73] [74] [32] | ||

| 11 [note 27] [note 28] (1969) | |||||||||||

| None [note 29] September 23, 1972 – February 25, 1986 | |||||||||||

| KBL | 12 [note 30] (1981) | ||||||||||

1981–87: Fourth Republic

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 4] |

Vice President | Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 |  |

Ferdinand Marcos (1917–1989) |

December 30, 1965 | February 25, 1986 [note 13] [note 25] |

Nacionalista | 10 (1965) |

Fernando Lopez December 30, 1965 – September 23, 1972 [note 26] |

[71] [72] [73] [74] [32] | ||

| 11 [note 27] [note 28] (1969) | |||||||||||

| None [note 29] September 23, 1972 – February 25, 1986 | |||||||||||

| KBL | 12 [note 30] (1981) | ||||||||||

| 11 | 2 |  |

Corazon Aquino (1933–2009) |

February 25, 1986 [note 32] |

June 30, 1992 | UNIDO | 13 (1986) |

Salvador Laurel | [77] [78] [70] | ||

1987–present: Fifth Republic

| No. overall [note 2] |

No. in era |

Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Took office | Left office | Party | Term [note 4] |

Vice President | Refs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1 |  |

Corazon Aquino (1933–2009) |

February 25, 1986 [note 32] |

June 30, 1992 | UNIDO | 13 (1986) |

Salvador Laurel | [77] [78] [70] | ||

| 12 | 2 |  |

Fidel Ramos (1928–) |

June 30, 1992 | June 30, 1998 | Lakas–NUCD | 14 (1992) |

Joseph Estrada | [80] [81] [82] | ||

| 13 | 3 |  |

Joseph Estrada (1937–) |

June 30, 1998 | January 20, 2001 [note 34] [note 7] |

LAMMP | 15 (1998) |

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo | [84] [85] [86] | ||

| 14 | 4 |  |

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (1947–) |

January 20, 2001 | June 30, 2010 | Lakas–NUCD | Vacant [note 15] January 20 – February 7, 2001 |

[87] [88] [86] [89] | |||

| Teofisto Guingona Jr. February 7, 2001 – June 30, 2004 | |||||||||||

| Lakas–Kampi–CMD | 16 (2004) |

Noli de Castro [note 35] June 30, 2004 – June 30, 2010 | |||||||||

| 15 | 5 |  |

Benigno Aquino III (1960–) |

June 30, 2010 | June 30, 2016 | Liberal | 17 (2010) |

Jejomar Binay | [90] [91] [92] | ||

| 16 | 6 | .jpg) |

Rodrigo Duterte (1945–) |

June 30, 2016 | Incumbent | PDP–Laban | 18 (2016) |

Leni Robredo |

[93] | ||

Timeline

See also

- President of the Philippines

- Vice President of the Philippines

- Prime Minister of the Philippines

- Constitution of the Philippines

- Timeline of Philippine history

- List of current heads of state and government

Notes

- ↑ The President has three official residences, but the Malacañang Palace is the President's principal workplace.[1] The other two are the Mansion House in Baguio, the official summer residence,[2] and the Malacañang sa Sugbo (Malacañang of Cebu), the official residence in Cebu.[3]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 In chronological order, the presidents started with Manuel L. Quezon,[23] who was then succeeded by Sergio Osmeña as the second president,[24] until the recognition of Emilio Aguinaldo[25] and José P. Laurel's[16] presidencies in the 1960s.[subnote 1][subnote 2] With Aguinaldo as the first president and Laurel as the third, Quezon and Osmeña are thus listed as the second and the fourth, respectively.[4][22]

- ↑ Emilio Aguinaldo, the official first president, was elected by the Malolos Congress and not by popular vote.[10][11]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 For the purposes of numbering, a presidency is defined as an uninterrupted period of time in office served by one person. For example, Manuel L. Quezon was elected in two consecutive terms and is counted as the second president (not the second and third).[subnote 3]

- ↑ Term began with the formal establishment of the Malolos Republic.[26][27][subnote 1]

- ↑ Term ended when Aguinaldo was captured by US forces in Palanan, Isabela, during the Philippine–American War.[4][subnote 4]

- 1 2 3 Later sought election or re-election to a non-consecutive term.[subnote 5]

- ↑ The Malolos Constitution did not provide for a vice president.[35]

- ↑ Term began with the formal establishment of the Philippine Commonwealth.[9][subnote 3]

- ↑ Died, in office, of tuberculosis in Saranac Lake, New York.[18]

- ↑ Term was originally until November 15, 1943, due to constitutional limitations as provided by the 1940 amendment of the 1935 Constitution, which shortened the terms of the president and the vice president from six to four years but allowed re-election.[subnote 5] Quezon was not intended to serve the full four years of the second term he won in the 1941 election because a ten-year presidency would have been considered excessive. In 1943, however, due to World War II, he and Vice President Sergio Osmeña, who was also re-elected, had to take an emergency oath of office, extending their tenure.[4][12]

- 1 2 See § 1943–45: Second Republic.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Unseated (lost re-election).[subnote 5]

- ↑ Sought an election for a full term, but was unsuccessful.

- 1 2 3 4 Prior to the ratification of the 1987 Constitution, there was no mechanism by which a vacancy in the vice presidency could be filled.[5][34] Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was the first president to fill such a vacancy under the provisions of the Constitution when she appointed Teofisto Guingona Jr.

- 1 2 Died, in office, of a heart attack in Clark Air Base, Pampanga.[19]

- 1 2 The Liberal Party was not yet a party in itself at the time, but only a wing of the Nacionalista Party.[41] It split and became a separate party by 1947.[42]

- ↑ Term began with the establishment of Japan's puppet Second Republic after it occupied the Philippines during World War II.[13][45] The Commonwealth continued its existence as a government in exile in Australia and the United States.[9][46] The Philippines had two concurrent presidents by this time:[4] a de jure (the Commonwealth president) and a de facto (Laurel).[15] Because of his status, he was not considered a legitimate president until the 1960s.[16]

- ↑ Term ended when he dissolved the Second Republic in the wake of Japan's surrender to the Allies two days prior.[16][45][subnote 2]

- ↑ Previously affiliated with the Nacionalista Party,[47] but was elected by the National Assembly under the Japanese-organized KALIBAPI, a "non-political service organization" as it described itself.[48] All pre-war parties were replaced by the KALIBAPI.[13][16]

- ↑ The 1943 Constitution did not provide for a vice president.[35][49]

- ↑ The Third Republic began when the Philippine Commonwealth ended on July 4, 1946.[4][51]

- ↑ The Liberal Party was split into two opposing wings for the 1949 election: the Avelino wing, led by presidential aspirant José Avelino, and the Quirino wing.[53]

- ↑ Died, in office, in a plane crash in Mount Manunggal, Cebu.[20][56]

- 1 2 Deposed in the People Power Revolution.[subnote 7]

- 1 2 Term ended upon Marcos' declaration of martial law.[35][subnote 8][subnote 9]

- 1 2 Imposed martial law, as a self-coup, on September 23, 1972, through Proclamation No. 1081, shortly before the end of his second and final term in 1973.[subnote 8]

- 1 2 Served concurrently as prime minister from June 12, 1978, to June 30, 1981.[71][subnote 9]

- 1 2 The 1973 Constitution was amended through a plebiscite held on January 27, 1984 to re-establish the vice presidency.[35][76][subnote 9]

- 1 2 The 1973 Constitution, as amended in 1981, did not place restrictions on re-election.[subnote 5]

- ↑ Martial law was lifted by Ferdinand Marcos on January 17, 1981, through Proclamation No. 2045,[17] marking the beginning of the Fourth Republic.[51]

- 1 2 Assumed presidency by claiming victory in the disputed 1986 snap election.[subnote 7]

- ↑ Corazon Aquino promulgated a provisional constitution called the 1986 Freedom Constitution on March 25, 1986.[79] It remained in effect until it was supplanted by the current constitution on February 2, 1987,[79] which ushered the Fifth Republic.[4]

- ↑ Deposed after the Supreme Court declared Estrada as resigned, and, as a result, the office of the president vacant, after the Second EDSA Revolution.[83]

- ↑ Allied with the Koalisyon ng Katapatan at Karanasan sa Kinabukasan (Coalition of Truth and Experience for Tomorrow).[89]

Subnotes

- 1 2 The Malolos Republic, an independent revolutionary state that is actually the first constitutional republic in Asia,[7][26] remained unrecognized by any country[28][29] until the Philippines acknowledged the government as its predecessor,[30] which it also calls the First Philippine Republic.[7][25][31] Aguinaldo was consequently counted as the country's first president.[6][25]</ref><ref group='subnote'>Aguinaldo had previously held the presidency of other short-lived national governments that preceded the Malolos Republic:[7][26] the Tejeros government (March 22 – November 2, 1897), the Republic of Biak-na-Bato (November 1 – December 20, 1897), a dictatorial government (May 24 – June 23, 1898), and a revolutionary government (June 23, 1898 – January 22, 1899).[10]

- 1 2 The Second Republic was later declared by the Supreme Court of the Philippines as a de facto, illegitimate government on September 17, 1945.[16] Its laws were considered null and void;[4][16] despite this, Laurel was included in the official roster of Philippine presidents in the 1960s.[16]</ref> The Commonwealth was re-established in the Philippines,[13] with Sergio Osmeña as the fourth president.[4][subnote 6] before it was proclaimed "reestablished as provided by law" on February 27, 1945.<ref>MacArthur, Douglas (February 27, 1945). "Speech of General Douglas MacArthur upon turning over to President Sergio Osmena the full powers and responsibilities of the Commonwealth Government under the Constitution". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Emilio Aguinaldo would be counted as the second president if he had won the 1935 election because the presidency was abolished and remained defunct until November 15, 1935. During that period, the executive power was exercised by the Governor-General of the US military government and the Insular Government, the precursor of the Philippine Commonwealth.<ref name='Agoncillo281'>Agoncillo & Guerrero 1970, p. 281

- ↑ Aguinaldo took the oath of allegiance to the US nine days later, effectively ending the republic.[7]<ref name='Tuckerp496'>Tucker 2009, p. 496

- 1 2 3 4 Before the ratification of the 1981 amendment of the 1973 Constitution, which removed the limit on re-election to the office for another six-year term,[32][33] presidents were elected to a four-year term with the possibility of re-election, as the amended 1935 Constitution specified: "No person shall serve as [p]resident for more than eight consecutive years."[34] When the 1987 Constitution was imposed and, in effect, superseded the previous constitutions, the president is no longer eligible for any re-election. It does, however, allow a person who had assumed the presidency to seek for a full six-year term if he or she has not yet "served as such for more than four years".<ref name='1987con'>"The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ The Commonwealth had already been temporarily restored in Tacloban on October 23, 1944, during the Battle of Leyte,<ref name='Commonwealthtemporary'>Staff writer(s); no by-line. (September 4, 2012). "Sergio Osmeña: Remembering the Grand Old Man of Cebu". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- 1 2 Ferdinand Marcos and Corazon Aquino both took their oath of office on February 25, 1986. In effect, the Philippines again had two simultaneous presidents, albeit for nine hours only.[66] Marcos was proclaimed on February 15 the winner of the widely denounced February 7 snap election,[66][67] which he called after opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr., his chief rival and Corazon's wife, was assasinated in 1983.[68] However, in a separate NAMFREL tally dated February 16, Aquino was found the actual duly-elected president.[69][70] The events led to the People Power Revolution on February 22–25, which forced Marcos to leave to exile in Hawaii and installed Aquino to the office.[66][68][70]

- 1 2 Accounts differ on when martial law was officially established. While sources such as Raymond Bonner have written that Proclamation No. 1081 was signed on September 23, 1972, Primitivo Mijares, a former journalist for Marcos, and the Bangkok Post stated that it was on September 17, only postdated to September 21 because of Marcos' numerological beliefs that were related to the number seven. Marcos claimed to have signed it on September 21, and as of 9 p.m. Philippine Standard Time (UTC+08:00) on September 22, the country was under martial law. He formally announced it in a live television and radio broadcast on September 23. The official date when martial law was set was on September 21 (because it was a date that was divisible by seven), but September 23 is generally considered the correct date because it was when the nation was informed and thus the proclamation was put into full effect.[17]</ref> General Order No. 1, which detailed the transfer of all powers to the president, was also issued, enabling Marcos to rule by decree.<ref name='martiallaw'>"Declaration of Martial Law". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- 1 2 3 On January 17, 1973, while martial law was still in effect, the 1973 Constitution was ratified, which suspended the 1935 Constitution and ended the Third Republic.[35][51] What Marcos called a New Society (Bagong Lipunan) began,[51] introducing a parliamentary form of government;[75] the vice presidency was abolished and the presidential succession provision was devolved to the prime minister.[35]

References

- ↑ Ortiguero, Romsanne (October 22, 2014). "TRAVEL Inside Malacañang Complex, 3 places to visit for a charming date with history". News5. TV5. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Mansion House". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ↑ Sisante, Jam (August 6, 2010). "Malacañang sa Sugbo still the president's official residence in Cebu". GMA News and Public Affairs. GMA Network. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "The Executive Branch". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- 1 2

- 1 2 Tucker 2009, p. 8

- 1 2 3 4 5 Staff writer(s); no by-line. (September 7, 2012). "The First Philippine Republic". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑

- 1 2 3 "The Commonwealth of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Emilio Aguinaldo". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, p. 203

- 1 2 3 4 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 62–64

- 1 2 3 4 Jose, Ricardo T. (1997). Afterword. His Excellency Jose P. Laurel, President of the Second Philippine Republic: Speeches, Messages and Statements, October 14, 1943 to December 19, 1944. By Laurel, José P. Manila: Lyceum of the Philippines in cooperation with the José P. Laurel Memorial Foundation. ISBN 971-91847-2-8. Retrieved June 18, 2016 – via Presidential Museum and Library.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (September 3, 1945). "The Philippines: End of a Puppet". Time. Retrieved July 5, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "Today is the birth anniversary of President Jose P. Laurel". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Staff writer(s); no by-line. (October 14, 2015). "Second Philippine Republic". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3

- 1 2 Tejero, Constantino C. (November 8, 2015). "The real Manuel Luis Quezon, beyond the posture and bravura". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- 1 2 Staff writer(s); no by-line. (April 16, 1948). "Heart Attack Fatal to Philippine Pres. Roxas". Schenectady Gazette. Manila. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- 1 2 "Death Anniversary of President Ramon Magsaysay". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. March 17, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (August 1, 2009). "Philippine ex-leader Aquino dies". BBC News. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Philippine Presidents". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ Quezon, Manuel L. (December 30, 1941). "Second Inaugural Address of President Quezon". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (October 19, 1961). "Sergio Osmena, Second President of the Philippines". Toledo Blade. Manila: Block Communications. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Pascual, Federico D., Jr. (September 26, 2010). "Macapagal legacy casts shadow on today's issues". The Philippine Star. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Araw ng Republikang Filipino, 1899" [Philippine Republic Day, 1899]. Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Guevara 1972, p. 28

- ↑

- ↑ Abueva, José V. (February 12, 2013). "Our only republic". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ Macapagal, Diosdado (June 12, 1962). "Address of President Macapagal on Independence Day". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Proclamation No. 533, s. 2013". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. January 9, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- 1 2 3 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 125–126

- ↑ "1973 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- 1 2 The 1935 Constitution:

- "The 1935 Constitution". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- "1935 Constitution amended". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Office of the Vice President". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Manuel L. Quezon". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 204

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 54–56

- ↑ "Sergio Osmeña". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 206

- 1 2 3 4 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 74–76

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 78

- 1 2 "Manuel Roxas". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, p. 207

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, p. 72

- ↑ Agoncillo & Guerrero 1970, p. 415

- 1 2 "Jose P. Laurel". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 66–67

- ↑ "The 1943 Constitution". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 205

- 1 2 3 4 "Third Republic". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (November 16, 2012). "The ritual climbing of the main stairs of...". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved July 21, 2016 – via Tumblr.

On the morning of April 17, 1948, Vice President Elpidio Quirino–fresh off a coast guard cutter from the Visayas–ascended the staircase to pay his respects to the departed President Manuel Roxas, and to take his oath of office as [p]resident of the Philippines. The country had been without a [p]resident for two days.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 80–82

- ↑ "Elpidio Quirino". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 208

- ↑ Staff writer(s); no by-line. (March 18, 1957). "Magsaysay Dead in Plane Crash". St. Petersburg Times. Manila: Times Publishing Company. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Ramon Magsaysay". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 209

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 85–88

- ↑ "Carlos P. Garcia". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 210

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 91–93

- ↑ "Diosdado Macapagal". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 211

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 96–98

- 1 2 3 Reaves, Joseph A. (February 26, 1986). "Marcos Flees, Aquino Rules". Chicago Tribune. Manila: Tribune Publishing. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Resolution No. 38". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. February 15, 1986. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- 1 2 Chandler & Steinberg 1987, pp. 431–442

- ↑ "1986 Tally Board". National Citizens' Movement for Free Elections. February 16, 1986. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 132–134

- 1 2 3 "Ferdinand E. Marcos". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, p. 212

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 101–104

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 108–110

- ↑ Sicat, Gerardo P. (September 23, 2015). "Marcos and his failure to provide for an orderly political succession". The Philippine Star. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

The transitional nature of the political system according to the 1973 Constitution was left undefined in view of the martial law government. This constitution adopted a British-style parliamentary system.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 130

- 1 2 "Corazon C. Aquino". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, p. 213

- 1 2 "Philippine Constitutions". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Fidel V. Ramos". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 214

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 142–143

- ↑ Calica, Aurea (January 21, 2001). "SC: People's welfare is the supreme law". The Philippine Star. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Joseph Ejercito Estrada". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 215

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 147–149

- ↑ "Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 216

- 1 2 PCDSPO 2015, pp. 153–155

- ↑ "Benigno S. Aquino III". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, p. 217

- ↑ PCDSPO 2015, pp. 159–161

- ↑ "Presidency and Vice Presidency by the Numbers: Rodrigo Roa Duterte and Leni Robredo". Presidential Museum and Library. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

Works cited

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A.; Guerrero, Milagros C. (1970). History of the Filipino People (3rd ed.). Malaya Books.

- Chandler, David Porter; Steinberg, David Joel (1987). In Search of Southeast Asia: A Modern History (Revised ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1110-0.

- Guevara, Sulpicio, ed. (2005) [1898]. The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899. Compiled, edited, and translated into English by Sulpicio Guevara. Manila: National Historical Institute (published 1972). ISBN 971-538-055-7 – via University of Michigan Library.

- Philippine Electoral Almanac (PDF) (Revised and expanded ed.). Manila: Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. 2015. ISBN 978-971-95551-6-2 – via Internet Archive.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. 1 (Illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Presidents of the Philippines. |

- Presidential Website

- Office of the President of the Philippines

- Presidential Museum and Library

- Philippines at worldstatesmen.org