List of Presidents of Italy

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Italy |

| Constitution |

|

Legislature |

|

| Foreign relations |

|

Related topics |

This is the list of the Presidents of the Italian Republic with the title Presidente della Repubblica since 1948. The Quirinal Palace (known in Italian as the Quirinale) in Rome is the official residence of the President of the Italian Republic.

The twelve Presidents came from only six Regions: three each from Campania (all born in Naples) and Piedmont, two each from Sardinia (both born in Sassari) and Tuscany, and one each from Liguria and Sicily.

Election

The President of the Republic is elected by Parliament in a joint session of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. In addition, the 20 regions of Italy appoint 58 representatives as special electors. Three representatives come from each region, save for the Aosta Valley, which appoints one, so as to guarantee representation for all localities and minorities.

According to the Constitution, the election must be held in the form of secret ballot, with the 315 Senators, the 630 Deputies and the 58 regional representatives all voting. A two-thirds vote is required to elect on any of the first three rounds of balloting; after that, a majority suffices. The election is presided over by the Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies, who calls for the public counting of the votes. The vote is held in the Palazzo Montecitorio, home of the Chamber of Deputies, which is expanded and re-configured for the event.

The President assumes office after having taken an oath before Parliament and delivering a presidential address.

Presidents of the Italian Republic (1946 – present)

- Parties

Traditionally, Presidents have not been members of any political party during their tenure, in order to be considered above partisan interests. The parties shown are those to which the President belonged at the time they took office.

- 1946–1993:

Liberal Party Christian Democracy Democratic Socialist Party Socialist Party

- Since 1994:

Democrats of the Left Independent

| № | Portrait | Name (Born-Died) |

Birthplace | Term of office | Political Party at time of election |

Election | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Enrico De Nicola (1877–1959) |

Naples | 28 June 1946 as Provisional Head of State 1 January 1948 [1] |

12 May 1948 | Italian Liberal Party | 1946 | |

| De Nicola was the first President of Italy. After a popular referendum on the 2nd of June 1946 resulted in the abrogation of the monarchy, the Constituent Assembly elected De Nicola Provisional Head of State on 28 June 1946. On 25 June 1947, De Nicola resigned from the post, citing health reasons, but the Constituent Assembly immediately re-elected him again the following day. After the Italian Constitution took effect, he was formally named the President of the Republic on 1 January 1948. He finally refused to be a candidate for the first constitutional election the following May. | ||||||||

| 2 |  |

Luigi Einaudi (1874–1961) |

Carrù, Cuneo |

12 May 1948 | 11 May 1955 | Italian Liberal Party | 1948 | |

| On 11 May 1948 Einaudi was elected the second President of Italy. Einaudi was a member of numerous cultural, economic and university institutions. He opened the exercise of the President's power to refer a law to the Chambers for review, doing it four times. He was also the first President who appointed a President of the Council who had not been mentioned by the majority party, in the case of Giuseppe Pella. | ||||||||

| 3 |  |

Giovanni Gronchi (1887–1978) |

Pontedera, Pisa |

11 May 1955 | 11 May 1962 | Christian Democracy | 1955 | |

| Gronchi's term in office, from 1955 to 1962, was marked by his ambition to bring about a gradual "opening to the left", whereby the Italian Socialist Party and Italian Communist Party would be brought back into the national government, and Italy would abandon NATO. There was however stiff parliamentary opposition to this project. In an attempt to escape the deadlock, in 1959 Gronchi appointed as Prime Minister a trusted member of his own left-wing faction of Christian Democracy, Fernando Tambroni. However Tambroni found himself surviving in Parliament only due to votes from the Italian Social Movement. This unforeseen “opening to the right” had serious consequences. In 1960 there were bad riots in several towns of Italy, particularly at Genoa, Licata and Reggio Emilia, where the police killed five people. Tambroni was forced to resign. The unhappy Tambroni experiment tarnished Gronchi's reputation for good, and until the end of his period of office he remained a lame-duck President. In 1962 he attempted to get a second mandate, with the powerful help of Enrico Mattei, but the attempt failed and Antonio Segni was elected instead. | ||||||||

| 4 |  |

Antonio Segni (1891–1972) |

Sassari | 11 May 1962 | 6 December 1964[2] | Christian Democracy | 1962 | |

| Segni was elected President of the Italian Republic on 6 May 1962 (854 to 443 votes). His two years at the Quirinale were marked by tensions with the block formed by Ugo La Malfa, the Italian Socialist Party and a part of the Christian Democracy pushing for social and structural reforms, unpopular to the conservative Segni. He suffered a serious cerebral hemorrhage while working at the presidential palace on 7 August 1964. In the interim, the President of the Senate Cesare Merzagora served as acting president. Segni was later accused of having tried to instigate a coup d'état (known as the Piano Solo) along with General Giovanni De Lorenzo during his presidency to frustrate the opening to the left. The plan included the identification of 731 politicians and trade unionists of the Italian left and their transfer to a NATO military base in Sardinia, the occupation of the state-owned broadcasting company RAI and the headquarters of left-wing newspapers and the intervention of the Force in case of communist meetings. | ||||||||

| 5 |  |

Giuseppe Saragat (1898–1988) |

Turin | 29 December 1964 | 29 December 1971 | Italian Democratic Socialist Party | 1964 | |

| Saragat was the first Social Democrat leader to become President of Italy. His election was the result of a rare case of unity of the Italian left, threatened by rumors of a possible neo-fascist coup during the presidency of Antonio Segni. On 28 December 1964 Saragat was elected President of the Italian Republic to the twenty-first ballot, thanks to the decisive votes of the Italian Socialist Party and Italian Communist Party. Saragat is now considered the father of the Italian social-democratic doctrine. A reformist, he accepted Italy's adherence to the Western alliance (he was in favor of the Marshall Plan and the entrance of the country into NATO); Saragat was convinced that social democracy could be politically added value and could have a position electorally hegemonic, as indeed was the case in the countries of northern Europe. During his presidency, he tried to promote cooperation between the Christian Democrats and the Socialists and Communists. | ||||||||

| 6 |  |

Giovanni Leone (1908–2001) |

Naples | 29 December 1971 | 15 June 1978[3] | Christian Democracy | 1971 | |

| In 1971 Leone succeeded Giuseppe Saragat as President of the Republic, elected with the votes of a centre-right majority of the Parliament (518 out of 996 votes, including those of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement). According to authoritative constitutionalists, his presidency was marked by a line marked full independence from political parties and the scrupulous respect of the institutions. During his presidency, he appointed knight of the work Silvio Berlusconi, the future Prime Minister. On 15 June 1978, following his involvement in the Lockheed bribery scandal, at the request of the Italian Communist Party and probably disagree with substantial parts of Christian Democracy, Leone was forced to resign from his office. | ||||||||

| 7 |  |

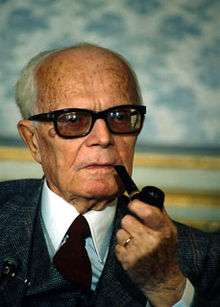

Sandro Pertini (1896–1990) |

Stella, Savona |

9 July 1978 | 29 June 1985[4] | Italian Socialist Party | 1978 | |

| Pertini was the first member of the Italian Socialist Party to become President of Italy. During his presidency, Pertini helped to make the figure of the President of the Republic as a symbol of the unity of the Italian people. His moral stature contributed to the citizens closer to the institutions, at a difficult time and dotted with criminal events such as the Years of Lead and the Bologna massacre. Pertini was the first President of the Republic to confer the task of forming a government to a person not from the Christian Democracy, Giovanni Spadolini, a Republican, who started his cabinet on 28 June 1981. He increasingly assumed an attitude of uncompromising complaint against organised crime by denouncing "the harmful activity against humanity" of the Mafia and warned never to confuse the phenomenon of crime Mafia, the Camorra and 'Ndrangheta with the places and people where are present. His death in Rome was viewed by many as a national tragedy, and he is one of modern Italy's most accomplished politicians. | ||||||||

| 8 |  |

Francesco Cossiga (1928–2010) |

Sassari | 3 July 1985 | 28 April 1992[5] | Christian Democracy | 1985 | |

| Following his resignation as president of the Senate in 1985, Cossiga was elected President of Italy. During his term in office he expressed the views that the Italian parties, especially Christian Democracy (his own party) and the Italian Communist Party, had to come to terms with the deep changes brought about by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War. These statements, soon dubbed "esternazioni", or "mattock blows" (picconate), were considered by many to be inappropriate for a President and, often, beyond his constitutional powers. Tension developed between Cossiga and the Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti. This tension emerged when Andreotti revealed the existence of Gladio, an underground organisation intended to resist a possible Soviet invasion through sabotage and guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. Cossiga acknowledged his involvement in the establishment of the organisation. On 28 April 1992 Cossiga resigned, two months before the end of his term. For the change in its attitude, Cossiga received various criticisms and taken away by almost all parties, with the exception of the Italian Social Movement who sided by his side in defense of the "pickaxe". | ||||||||

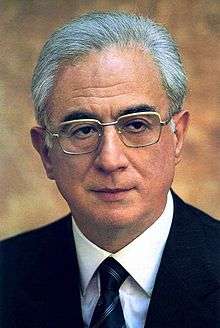

| 9 |  |

Oscar Luigi Scalfaro (1918–2012) |

Novara | 28 May 1992 | 15 May 1999[4] | Christian Democracy | 1992 | |

| Scalfaro was elected on 25 May 1992, after a two-week stalemate of unsuccessful attempts to reach agreement. The assassination of anti-Mafia magistrate Giovanni Falcone prompted his election. A staunch Catholic, and in the past a rather conservative and anti-communist politician, Scalfaro nevertheless distrusted many members of Christian Democracy who changed support to Forza Italia, and was consistently on bad terms with its leader and Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi. It was one of the most controversial presidencies of Italian history: although strongly supported by political parties survived the whirlwind of Tangentopoli, has led to strong opposition, faced with a decision that no one would know to expect a politician landed almost by accident at the Quirinale. In 1993 broke out the "SISDE scandal", which Scalfaro strongly denounced as a reprisal of the political class overwhelmed by Tangentopoli against him. Scalfaro was the last Christian Democrat to become President of Italy. | ||||||||

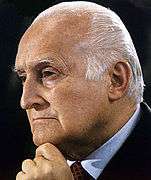

| 10 |  |

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (1920–2016) |

Livorno | 18 May 1999 | 15 May 2006[4] | Independent[6] | 1999 | |

| Ciampi was elected with a broad majority, and was the second president ever to be elected at the first ballot. He usually refrained from intervening directly into the political debate while serving as President. However, he often addressed general issues, without mentioning their connection to the current political debate, in order to state his opinion without being too intrusive. His interventions frequently stressed the need for all parties to respect the constitution and observe the proprieties of political debate. He was generally held in high regard by all political forces represented in parliament. As President, Ciampi was not considered to be close to the positions of the Vatican, providing a sort of unofficial alternation after the devout Oscar Luigi Scalfaro. He often praised patriotism, not always a common feeling in Italy because of its abuse by the fascist regime; Ciampi, however, seemed to want to stress self-confidence rather than nationalism. Ciampi was encouraged by many to stand for a second term of office, but he refused on grounds of age. Both the centre-right and centre-left praised his work as a non-partisan institutional guarantor. | ||||||||

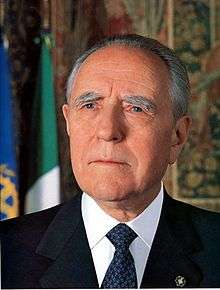

| 11 |  |

Giorgio Napolitano (1925–) |

Naples | 15 May 2006 | 14 January 2015[7] | Democrats of the Left | 2006 | |

| Independent | 2013 | |||||||

| Napolitano is the longest serving President in the history of the Italian Republic. Napolitano was elected on 10 May 2006 following the fourth round of voting. At the age of 80, he became the first former member of Italian Communist Party to become President of Italy, as well as the third Neapolitan after Enrico De Nicola and Giovanni Leone. In November 2011, after barely surviving a motion of no confidence in December 2010, Silvio Berlusconi resigned from his post as Prime Minister, having lost the trust of the Parliament following increasingly dramatic financial and economic conditions. President Napolitano then decided to appoint former EU commissioner Mario Monti as a technocratic PM. Napolitano's management of the events caused unprecedented worldwide media exposure regarding his role as President. On 20 April 2013, was requested by a wide array parliamentary willingness to be re-elected, which he has given, being elected to the sixth vote with 738 votes out of 997 eligible voters and becoming the first President of the Republic to be elected for a second term. On 24 April 2013 he appointed Enrico Letta with the task of forming a new government, four days later Letta was sworn as Prime Minister in Palazzo Chigi. On February 2014 following tensions in the Democratic Party, Letta resigned and Napolitano appointed Matteo Renzi, the Democratic Party secretary, as the new Prime Minister. Napolitano resigned on 14 January 2015, citing his age. | ||||||||

| 12 |  |

Sergio Mattarella (1941–) |

Palermo | 3 February 2015 | Incumbent | Independent[8] | 2015 | |

| Mattarella was elected with a broad majority of 665 votes on the fourth ballot; he was voted not only by the Democratic Party, which put forward his name, but also by the New Centre-Right, Left Ecology Freedom and Civic Choice. Mattarella is the first President from Sicily in the history of the Republic; he is also the first judge of the Constitutional Court to become President of the Republic. On 6 May 2015 Mattarella signed the new Italian electoral law, known as Italicum, which provides for a two-round system based on party-list proportional representation, corrected by a majority bonus and a 3% election threshold. | ||||||||

Source: www.quirinale.it

Substitution of the Head of State

In various occasions, in the history of the Italian republic, officials had to step in in the absence of a Head of State (e.g. in the case of a President's resignation or ill health). Only Enrico De Nicola, who was elected as Provisional Head of State by the Constitutional Assembly on 28 June 1946, had an official title and took residence in the Quirinal Palace. All the other men took only the powers, but not the title, of Head of State. After the adoption of the Italian Constitution in 1948, the President of the Senate is eligible to take the powers of Head of State in case of absence of the President of the Republic.

- Alcide De Gasperi (1881–1954) exercised the powers of Provisional Head of State as Prime Minister of Italy between the departure of King Umberto II on 12 June 1946, and the proclamation of Enrico de Nicola as Head of State by the Constitutional Assembly.

- Enrico De Nicola (1877–1959) was the only man who had the title, and not only the powers, of Provisional Head of State. He assumed the office on 1 July 1946, and became officially the President of the Republic on 1 January 1948, as ordered by the new Constitution.

- Cesare Merzagora (1898–1991), as President of the Senate, assumed temporary powers for President Segni after his cerebral ictus of 10 August 1964, and assumed full powers after his resignation of 6 December and until 29 December 1964.

- Amintore Fanfani (1908–1999), as President of the Senate, assumed powers from President Leone after his resignation for a bribery scandal on 15 June 1978. He exercised the powers until 9 July 1978.

- Francesco Cossiga (1928–2010), as President of the Senate, assumed powers from President Pertini on 29 June 1985, just four days before taking office as President.

- Giovanni Spadolini (1925–1994), as President of the Senate, assumed powers from President Cossiga on 28 April 1992. He exercised the powers until 28 May 1992.

- Nicola Mancino (born 1931), as President of the Senate, assumed powers from President Scalfaro on 15 May 1999. He exercised the powers until 18 May 1999.

- Pietro Grasso (born 1945), as President of the Senate, assumed powers from President Napolitano on 14 January 2015. He exercised the powers until 3 February 2015.

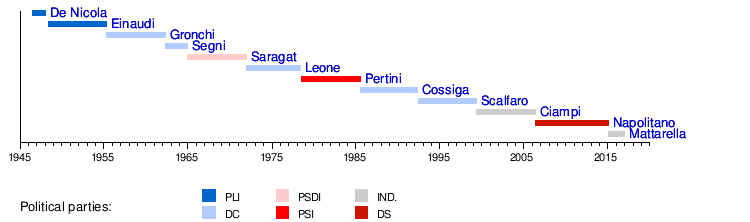

Timeline

Living former Presidents

There is one living former Italian President:

- Living former Presidents

Giorgio Napolitano

Giorgio Napolitano

served 2006–2015

See also

- List of Italian Monarchs for previous Italian Heads of State between 1861 and 1946

- List of Presidents of Italy by time in office

- Politics of Italy

- Prime Minister of Italy

- List of Prime Ministers of Italy

- Lists of incumbents

References

- ↑ He did not want to be called President of the Republic, but only Temporary Chief of State, as he had been elected by the Constituent Assembly. Nevertheless, according to the Italian Constitution approved in 1947, he assumed the title of President on 1 January 1948.

- ↑ Resigned for illness.

- ↑ Resigned after a bribery scandal.

- 1 2 3 Resigned to speed the swearing-in ceremony of his successor, who had already been elected.

- ↑ Resigned.

- ↑ He had been a member of the Action Party, but the party ended its existence in 1947.

- ↑ Resigned saying that his age could permit no more to exercise properly all his duties.

- ↑ He had been a member of the Christian Democracy, of the Italian People's Party, of the Daisy and of the Democratic Party, but he quit political commitment when becoming a judge in 2009.

External links

- (Italian) Presidenza della Repubblica - official site of the President of Italian Republic

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Presidents of Italy. |