List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

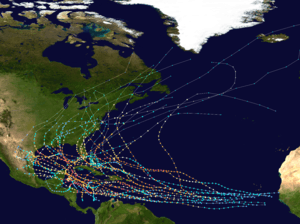

The list of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes encompasses 31 tropical cyclones that reached Category 5 strength on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale within the Atlantic Ocean (north of the equator), Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. Hurricanes of such intensity are somewhat infrequent in the Atlantic basin, occurring only once every three years on average.

Only five times—in the 1932, 1933, 1961, 2005, and 2007 hurricane seasons—has more than one Category 5 hurricane formed. Only in 2005 have more than two Category 5 hurricanes formed, and only in 2007 has more than one made landfall at Category 5 strength.[1]

Statistics

| Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

A Category 5 hurricane has sustained winds greater than 156 miles per hour (251 km/h). "Sustained winds" refers to the average wind speed observed over one minute at 10 metres (32 ft 9.7 in) above ground, which is the standard height windspeed is measured at to avoid interference by obstacles and obstructions. Brief gusts in hurricanes are typically up to 50 percent higher than sustained winds.[2] Because a hurricane is (usually) a moving system, the wind field is asymmetric, with the strongest winds on the right side (in the Northern Hemisphere), relative to the direction of motion. The highest winds given in advisories are those from the right side.[3]

Between 1924 and 2016, 31 hurricanes were recorded at Category 5 strength. No Category 5 hurricanes were observed officially before 1924. It can be presumed that earlier storms reached Category 5 strength over open waters, but the strongest winds were not measured. The anemometer, a device used for measuring wind speed, was invented in 1846. However, during major hurricane strikes the instruments as a whole were often blown away, leaving the hurricane′s peak intensity unrecorded. For example, as the Great Beaufort Hurricane of 1879 struck North Carolina, the anemometer cups were blown away when indicating 138 mph (222 km/h).[4]

A reanalysis of weather data is ongoing by researchers who may upgrade or downgrade other Atlantic hurricanes currently listed at Categories 4 and 5.[5] For example, the 1825 Santa Ana hurricane is suspected to have reached Category 5 strength.[6] Furthermore, paleotempestological research aims to identify past major hurricanes by comparing sedimentary evidence of recent and past hurricane strikes. For example, a "giant hurricane" significantly more powerful than Hurricane Hattie (Category 5) has been identified in Belizean sediment, having struck the region sometime before 1500.[7]

Officially, the decade with the most Category 5 hurricanes is 2000–2009, with eight Category 5 hurricanes having occurred: Isabel (2003), Ivan (2004), Emily (2005), Katrina (2005), Rita (2005), Wilma (2005), Dean (2007), and Felix (2007). The previous decades with the most Category 5 hurricanes were the 1930s and 1960s, with six occurring between 1930 and 1939 (before naming began) .[1]

Seven Atlantic hurricanes—Camille, Allen, Andrew, Isabel, Ivan, Dean and Felix—reached Category 5 intensity on more than one occasion; that is, by reaching Category 5 intensity, weakening to a Category 4 or lower, and then becoming a Category 5 again. Such hurricanes have their dates shown together. Camille, Andrew, Dean and Felix each attained Category 5 status twice during their lifespans. Allen, Isabel and Ivan reached Category 5 intensity on three separate occasions. However, no Atlantic hurricane has reached Category 5 intensity more than three times during its lifespan. The November 1932 Cuba hurricane holds the record for most time spent as a Category 5 (although it took place before satellite or reconnaissance so the record may be somewhat suspect).[1][8]

The minimum pressure of the more recent systems was measured by recon aircraft using dropsondes, or by determining it from satellite imagery using the Dvorak technique. For older storms, pressures are often incomplete. The only readings came from ship reports, land observations, or aircraft reconnaissance. None of these methods can provide constant pressure measurements. Thus, sometimes the only measurement can be from when the hurricane was not a Category 5. Consequently, the lowest measurement is sometimes unrealistically high for a Category 5 hurricane. For example, the 1938 New England hurricane had its lowest recorded pressure recorded while it was a Category 3 storm.

These pressure values do not directly correlate with the maximum winds. This happens because the wind speed of a hurricane depends on both its size and how rapidly the pressure drops as the hurricane's center approaches. Thus, a hurricane in an environment of high ambient pressure will have stronger winds than a hurricane in an environment of low ambient pressure, even if they have identical central pressures.[9]

Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

| Storm name |

Season | Dates as a Category 5 |

Time as a Category 5 (hours) |

Peak one-minute sustained winds |

Pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | hPa | inHg | |||||

| "Cuba" | 1924 | October 19 | 12 | 165 | 270 | 910 | 26.87 | |

| San Felipe II-"Okeechobee" | 1928 | September 13–14 | 12 | 160 | 260 | 929 | 27.43 | |

| "Bahamas" | 1932 | September 5–6 | 24 | 160 | 260 | 921 | 27.20 | |

| "Cuba" | 1932 | November 5–8 | 78 | 175 | 280 | 915 | 27.02 | |

| "Cuba–Brownsville" | 1933 | August 30 | 12 | 160 | 260 | 930 | 27.46 | |

| "Tampico" | 1933 | September 21 | 12 | 160 | 260 | 929 | 27.43 | |

| "Labor Day" | 1935 | September 3 | 18 | 185 | 295 | 892 | 26.34 | |

| "New England" | 1938 | September 19–20 | 18 | 160 | 260 | 940 | 27.76 | |

| Carol | 1953 | September 3 | 12 | 160 | 260 | 929 | 27.43 | |

| Janet | 1955 | September 27–28 | 18 | 175 | 280 | 914 | 27.0 | |

| Carla | 1961 | September 11 | 18 | 175 | 280 | 931 | 27.49 | |

| Hattie | 1961 | October 30–31 | 18 | 160 | 260 | 920 | 27.17 | |

| Beulah | 1967 | September 20 | 18 | 160 | 260 | 923 | 27.26 | |

| Camille | 1969 | August 16–18† | 30 | 175 | 280 | 900 | 26.58 | |

| Edith | 1971 | September 9 | 6 | 160 | 260 | 943 | 27.85 | |

| Anita | 1977 | September 2 | 12 | 175 | 280 | 926 | 27.34 | |

| David | 1979 | August 30–31 | 42 | 175 | 280 | 924 | 27.29 | |

| Allen | 1980 | August 5–9† | 72 | 190 | 305 | 899 | 26.55 | |

| Gilbert | 1988 | September 13–14 | 24 | 185 | 295 | 888 | 26.22 | |

| Hugo | 1989 | September 15 | 6 | 160 | 260 | 918 | 27.11 | |

| Andrew | 1992 | August 23–24† | 16 | 175 | 280 | 922 | 27.23 | |

| Mitch | 1998 | October 26–28 | 42 | 180 | 285 | 905 | 26.72 | |

| Isabel | 2003 | September 11–14† | 42 | 165 | 270 | 915 | 27.02 | |

| Ivan | 2004 | September 9–14† | 60 | 165 | 270 | 910 | 26.87 | |

| Emily | 2005 | July 16 | 6 | 160 | 260 | 929 | 27.43 | |

| Katrina | 2005 | August 28–29 | 18 | 175 | 280 | 902 | 26.64 | |

| Rita | 2005 | September 21–22 | 24 | 180 | 285 | 895 | 26.43 | |

| Wilma | 2005 | October 19 | 18 | 185 | 295 | 882 | 26.05 | |

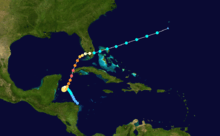

| Dean | 2007 | August 18–21† | 24 | 175 | 280 | 905 | 26.72 | |

| Felix | 2007 | September 3–4† | 24 | 175 | 280 | 929 | 27.43 | |

| Matthew | 2016 | September 30 – October 1 | 6 | 160 | 260 | 934 | 27.58 | |

| Reference=[1] †= Attained Category 5 status more than once | ||||||||

Climatology

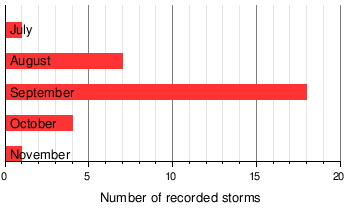

Thirty-one Category 5s have been recorded in the Atlantic basin since 1851, when records began. Only one Category 5 has been recorded in July, eight in August, nineteen in September, four in October, and one in November. There have been no officially recorded June or off-season Category 5 hurricanes.[1]

The July and August Category 5s reached their high intensities in both the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. These are the areas most favorable for tropical cyclone development in those months.[1][10]

September sees the most Category 5 hurricanes. This coincides with the climatological peak of the Atlantic hurricane season, which occurs in early September.[11] September Category 5s reached their strengths in any of the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea, and open Atlantic. These places are where September tropical cyclones are likely to form.[10] Many of these hurricanes are either Cape Verde-type storms, which develop their strength by having a great deal of open water; or so-called Bahama busters, which intensify over the warm Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico.[12]

All five Category 5s in October and November reached their intensities in the western Caribbean, a region that Atlantic hurricanes strongly gravitate toward late in the season.[10] This is due to the climatology of the area, which sometimes has a high-altitude anticyclone that promotes rapid intensification late in the season, as well as warm waters. Originally, there were only three Category 5s discovered in October, but reanalysis found out that a Hurricane in 1924 also reached that intensity during the month, so four Category 5s developed in October.[1]

Listed by month

|

|

Landfalls

All Atlantic Category 5 hurricanes have made landfall at some location at some strength. Most Category 5 hurricanes in the Atlantic make landfall because of their proximity to land in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, where the usual synoptic weather patterns carry them towards land, as opposed to the westward, oceanic mean track of Eastern Pacific hurricanes.[13] Thirteen of the storms made landfall while at Category 5 intensity;[1] 2007 is the only year in which two storms made landfall at this intensity.[1]

Many of these systems made landfall shortly after weakening from a Category 5. This weakening can be caused by dry air near land, shallower waters due to shelving, interaction with land, or cooler waters near shore.[14] In southern Florida, the return period for a Category 5 hurricane is roughly once every 50 years.[15]

The following table lists these hurricanes by landfall intensity.

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Category 5 Pacific hurricanes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W. "Tropical Cyclone FAQ Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W. "Tropical Cyclone FAQ Subject: D6) Why are the strongest winds in a hurricane typically on the right side of the storm?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- ↑ Hudgins, James E. (2000). "Tropical cyclones affecting North Carolina since 1586" (PDF). National Weather Service Office Blacksburg, Virginia. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- ↑ Staff writer (2010-06-08). "Re-analysis Project". Hurricane Research Division — Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Project. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Donnelly, J. P. (2005). "Evidence of Past Intense Tropical Cyclones from Backbarrier Salt Pond Sediments: A Case Study from Isla de Culebrita, Puerto Rico, USA" (PDF). Journal of Coastal Research. SI42: 201–210. ISSN 0749-0208. Retrieved 2010-11-26.

- ↑ Mccloskey, T; G Keller (2009). "5000 year sedimentary record of hurricane strikes on the central coast of Belize". Quaternary International. 195 (1-2): 53–68. Bibcode:2009QuInt.195...53M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2008.03.003. ISSN 1040-6182. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- ↑ Rappaport, Edward N. "Addendum Hurricane Andrew". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W. "Tropical Cyclone FAQ Subject: D9) What causes each hurricane to have a different maximum wind speed for a given minimum sea-level pressure?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-03-16.

- 1 2 3 Staff writer (2010). "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Dorst, Neal (2010-06-10). "Tropical Cyclone FAQ G1) When is hurricane season ?". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W. (2010-06-08). "Tropical Cyclone FAQ A2) What is a "Cape Verde" hurricane?". Hurricane Research Division — Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W (2010-06-08). "Tropical Cyclone FAQ G8) Why do hurricanes hit the East coast of the U.S., but never the West coast?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ↑ Knabb, Richard D.; Rhome, Jamie R.; Brown, Daniel P. (2005-12-20). "Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Katrina" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 4. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ Landsea, Christopher W.; Franklin, James L.; McAdie, Colin J.; Beven, John L.; Gross, James M.; Jarvinen, Brian R.; Pasch, Richard J.; Rappaport, Edward N.; Dunion, Jason P.; Dodge, Peter P. (2004). "A Reanalysis of Hurricane Andrew's Intensity" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 85 (11): 1699. Bibcode:2004BAMS...85.1699L. doi:10.1175/BAMS-85-11-1699. ISSN 0003-0007. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

External links