Line of Actual Control

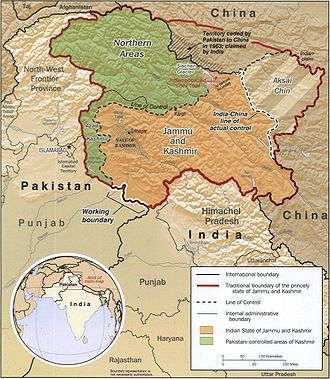

The Line of Actual Control (LAC) is a demarcation line that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory.[1]

There are two common ways in which the term "Line of Actual Control" is used. In the narrow sense, it refers only to the line of control in the western sector of the borderland between the two countries. In that sense, the LAC forms the effective border between the two countries together with the (also disputed) McMahon Line in the east, and a small undisputed section in between. In the wider sense, it can be used to refer to both the western line of control and the MacMahon Line, in which sense it is the effective border between India and the People's Republic of China (PRC).

The entire Sino-Indian border (including the western LAC, the small undisputed section in the centre, and the MacMahon Line in the east) is 4,056 km (2520 mi) long and traverses five Indian states: Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.[2] On the Chinese side, the line traverses the Tibet Autonomous Region. The demarcation existed as the informal cease-fire line between India and China after the 1962 conflict until 1993, when its existence was officially accepted as the 'Line of Actual Control' in a bilateral agreement.[3] However, Chinese scholars claim that the Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai first used the phrase in a letter addressed to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru dated 24 October 1959.

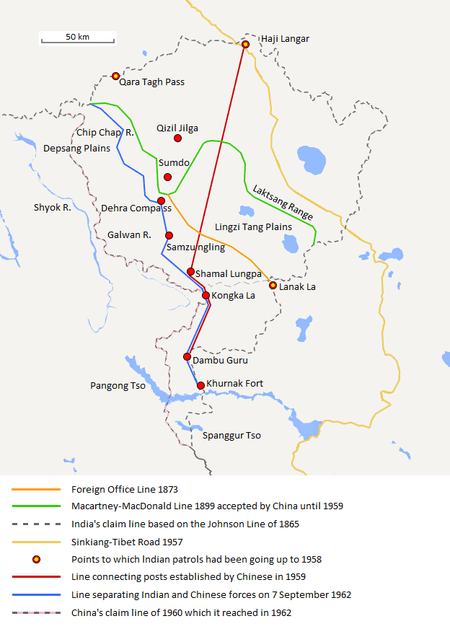

Although no official boundary had ever been negotiated between China and India, the Indian government even today claims a boundary in the western sector similar to the Johnson Line of 1865, whereas the PRC government considers a line similar to the Macartney–MacDonald Line of 1899 as the boundary.[4][5]

In a letter dated 7 November 1959, Zhou told Nehru that the LAC consisted of "the so-called McMahon Line in the east and the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west". During the Sino-Indian War (1962), Nehru refused to recognise the line of control: "There is no sense or meaning in the Chinese offer to withdraw twenty kilometers from what they call 'line of actual control'. What is this 'line of control'? Is this the line they have created by aggression since the beginning of September? Advancing forty or sixty kilometers by blatant military aggression and offering to withdraw twenty kilometers provided both sides do this is a deceptive device which can fool nobody."[6]

Zhou responded that the LAC was "basically still the line of actual control as existed between the Chinese and Indian sides on 7 November 1959. To put it concretely, in the eastern sector it coincides in the main with the so-called McMahon Line, and in the western and middle sectors it coincides in the main with the traditional customary line which has consistently been pointed out by China."[7]

The term "LAC" gained legal recognition in Sino-Indian agreements signed in 1993 and 1996. The 1996 agreement states, "No activities of either side shall overstep the line of actual control."[8] The Indian government claims that Chinese troops continue to illegally enter the area hundreds of times every year.[9] In 2013, there was a three-week standoff between Indian and Chinese troops 30 km southeast of Daulat Beg Oldi. It was resolved and both Chinese and Indian troops withdrew in exchange for a Chinese agreement to destroy some military structures over 250 km to the south near Chumar that the Indians perceived as threatening.[10] Later the same year, it was reported that Indian forces had already documented 329 sightings of unidentified objects over a lake in the border region, between last August and February . They recorded 155 such intrusions. Later some of the objects were identified as planets by the Indian Institute of Astrophysics as Venus and Jupiter appearing brighter as a result of the different atmosphere at altitude and due to the increased use of surveillance drones.[11] In October 2013, India and China signed a border defence cooperation agreement to ensure that patrolling along the LAC does not escalate into armed conflict.[12]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Line of Actual Control

- ↑ "Another Chinese intrusion in Sikkim", OneIndia, Thursday, 19 June 2008. Accessed: 2008-06-19.

- ↑ "Agreement On The Maintenance Of Peace Along The Line Of Actual Control In The India-China Border". stimson.org. The Stimson Center.

- ↑ Sino Indian Relations. "India-China Border Dispute". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ↑ Verma, Colonel Virendra Sahai. "Sino-Indian Border Dispute At Aksai Chin - A Middle Path For Resolution" (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Maxwell, Neville (1999). "India's China War". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Chou's Latest Proposals"

- ↑ Sali, M.L., (2008) India-China border dispute, p. 185, ISBN 1-4343-6971-4.

- ↑ "Chinese Troops Had Dismantled Bunkers on Indian Side of LoAC in August 2011". India Today. April 25, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ↑ Defense News. "India Destroyed Bunkers in Chumar to Resolve Ladakh Row". Defense News. May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ↑ "India: Army 'mistook planets for spy drones'". BBC. 25 July 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ Reuters. China, India sign deal aimed at soothing Himalayan tension All though due to some media reports show that the chinese troops enetred India for about over hundreds of kilometeres but in reality the actual data still lies in dilemma.

Sources

- Why China is playing hardball in Arunachal by Venkatesan Vembu, Daily News & Analysis, 13 May 2007

- Two maps of Kashmir: maps showing the Indian and Pakistani positions on the border.