Lin Zhao

| Lin Zhao 林昭 | |

|---|---|

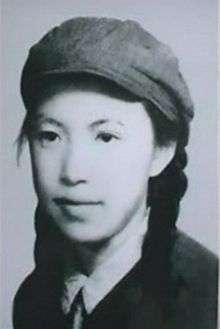

Lin Zhao, undated photo | |

| Born |

Peng Lingzhao 16 December 1932 Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China |

| Died |

29 April 1968 (aged 35) Longhua Airport, Shanghai, China |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Alma mater | Peking University |

| Parent(s) |

Peng Guoxian (彭国彦) Xu Xianmin (许宪民) |

| Relatives | Xu Jinyuan (许金元) (uncle) |

Lin Zhao (Chinese: 林昭; December 16, 1932 – April 29, 1968), born Peng Lingzhao (彭令昭), was a prominent dissident who was imprisoned and later executed by the People's Republic of China during the Cultural Revolution for her criticism of Mao Zedong's policies.

Early life

Peng Lingzhao was born to a prominent family in Suzhou, Jiangsu province. By age 16, she had already joined an underground Communist cell and was writing articles criticizing the corruption of the Nationalist government under the pen name Lin Zhao. Three months before the Communists took power in mainland China, she ran away from home in order to attend a journalism school run by the Communists. During her tenure, she was assigned to work in a group to administer land reform in the countryside, where she willfully took an active role in the torture and violent deaths of landlords as justified by the principle of class struggle.

Dissident

Lin later enrolled in the Chinese literature department at Peking University where she became an outspoken dissident during the Hundred Flowers Movement of 1957. During this time, intellectuals such as herself were encouraged to criticize the Communist Party of China, but were later punished for doing so.[1] As punishment, Lin was ordered to perform menial tasks for the university which included killing mosquitoes as part of the Four Pests Campaign and cataloguing old newspapers for the reference library of the university's journalism department.

In October 1960 while on medical parole in Suzhou, Lin Zhao was arrested along with other dissidents for helping to publish an underground magazine that criticized the Communist Party in reaction to the devastation wrought on the Chinese people by the government during the Great Leap Forward. She was later sentenced to 20 years imprisonment as a political prisoner[2] where she was repeatedly beaten and tortured.

Lin was a convert to Christianity, having attended a Christian missionary school before studying at Peking University. As she languished in prison, she became more committed to her faith as her belief in Communism waned.[3]

While in prison, Lin famously wrote hundreds of pages of critical commentary about Mao Zedong using hairpins and bamboo slivers with her own blood as ink. In a report dated December 5, 1966, it was recommended that Lin be executed based on "serious crimes" which included, "1. Insanely attacking, cursing, and slandering our great Chinese Communist Party and our great leader Chairman Mao... 2. Regarding the proletarian dictatorship and socialist system with extreme hostility and hatred... 3. Publicly shouting reactionary slogans, disrupting prison order, instigating other prisoners to rebel, and broadcasting threats to take revenge on behalf of executed counter-revolutionary criminals... 4. Persistently maintaining a reactionary stand, refusing to admit her crimes, resisting discipline and education, and defying reform..."

Lin was executed by gunshot in 1968.[1] Lin's family was made not aware of her death until a Communist Party official approached her mother to collect a five-cent fee for the bullet used to kill her.[4]

Rehabilitation

In 1981, under the government of Deng Xiaoping, Lin was officially exonerated of her crimes and rehabilitated.[5] Despite her rehabilitation, the Chinese government remains reluctant to allow commemoration or discussion of Lin's life and writings. In 2013, on the 45th anniversary of Lin's execution, a number of activists attempted to visit Lin's grave near her hometown of Suzhou but were restricted by government security officials.[3][4]

Legacy

The story of Lin Zhao's life was obscure and little-known until it was brought to light by documentary filmmaker Hu Jie, whose 2005 documentary In Search Of Lin Zhao's Soul won numerous awards. She is also featured in several chapters of Philip Pan's 2008 book, Out of Mao's Shadow.

Many of her essays, letters, and diaries were preserved by Communist Party officials for possible future use as propaganda. Some time after her death, a police official agreed to risk his own life in order to smuggle many of Lin's writings to her friends and family.[6] Hu Jie was able to acquire some of these writings for use in his documentary. Currently, a collection of her works is being held at the Hoover Institute at Stanford University.[7]

References

- 1 2 Pan, Philip P (2008), Out of Mao's Shadow, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 1-41653705-8.

- ↑ Zhong, Jin (2004), "In Search of the Soul of Lin Zhao" (PDF), China Rights Forum, HRI China (3).

- 1 2 Wickenkamp, Carol. "Chinese Regime Blocks Commemoration of Executed Dissident Lin Zhao". The Epoch Times. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- 1 2 Marquand, Robert. "Tiananmen Anniversary: Memory of executed poet resonates". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ↑ Boehler, Patrick. "Remembrance of dissident Lin Zhao obstructed on 45th execution anniversary". SCMP. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ↑ Pan, Philip. "A Past Written In Blood". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ↑ "Letters and diaries of Chinese political activist Lin Zhao opened". The Hoover Institution Archives. Retrieved 25 June 2014.