Larry McDonald

| Larry McDonald | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 7th district | |

|

In office January 3, 1975 – September 1, 1983 | |

| Preceded by | John W. Davis |

| Succeeded by | George Darden |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Lawrence Patton McDonald April 1, 1935 Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died |

September 1, 1983 (aged 48) near Sakhalin, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

Anna McDonald (née Tryggvadottir) (?–?; divorced) Kathryn McDonald (née Jackson) (1975–1983; his death) |

| Profession | Physician |

| Religion | Independent Methodist |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1959–1961 |

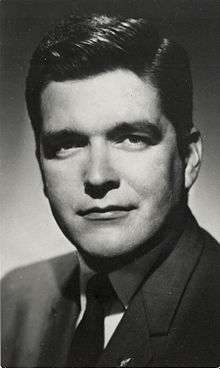

Lawrence Patton "Larry" McDonald (April 1, 1935 – September 1, 1983) was an American politician and a member of the United States House of Representatives, representing Georgia's 7th congressional district as a Democrat from 1975 until he was killed while a passenger on board Korean Air Lines Flight 007 when it was shot down by Soviet interceptors. As of 2016, McDonald is the most recent member of Congress to die violently while in office.

A conservative Democrat, McDonald was active in numerous civic organizations and maintained a very conservative voting record in Congress. He was the prime mover in dedicating two statues in the US Congress Capitol Rotunda to prominent African-American leaders. He was known for his staunch opposition to communism. He was the second president of the John Birch Society and also a cousin of General George S. Patton.[1]

Early life and career

Larry McDonald was born and raised in Atlanta, Georgia, more specifically in the eastern part of the city that is in DeKalb County. As a child, he attended several private and parochial schools before attending a non-denominational high school.[1] He spent two years at high school before graduating in 1951.[1][2] He studied at Davidson College from 1951 until 1953, spending time studying history.[1][2] He entered the Emory University School of Medicine at the age of 17, graduating in 1957.[1][2] He interned at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. He trained as a Urologist at the University of Michigan Hospital under Prof. Reed M. Nesbit. Following completion in 1966 he returned to Atlanta and entered practice with his father.

From 1959 to 1961, he served as a flight surgeon in the United States Navy stationed at the Keflavík naval base in Iceland. McDonald married an Icelandic national, Anna Tryggvadottir, with whom he would eventually have three children: Tryggvi Paul, Callie Grace, and Mary Elizabeth.[1] It was in Iceland that McDonald first began to take note of communism. He felt the U.S. Embassy in Reykjavik was doing things advantageous to the Communists; therefore he went to his commanding officer, but was told he did not understand the big picture.[1]

After his tour of service he practiced medicine at the McDonald Urology Clinic in Atlanta. He took an increasing interest in politics, reading books on political history and foreign policy.[1] He joined the John Birch Society—a conservative, anti-communist organization—in 1966 or 1967.[3][4] McDonald's passionate preoccupation with politics led to a divorce from his first wife.[1] McDonald made one unsuccessful run for Congress in 1972 before being elected in 1974. In 1975, he married Kathryn Jackson, whom he met while giving a speech in California.[1] He fathered two children with Kathryn.

McDonald served as a member on the Georgia State Medical Education Board (as chairman 1969–1974[2]), the National Historical Society, the Cobb County Chamber of Commerce, and received numerous civil honors.

Political career

In 1974, McDonald ran for Congress against incumbent John W. Davis in the Democratic primary as a conservative who was opposed to mandatory federal school integration programs. McDonald successfully criticized Davis for being one of only two Georgia congressmen to vote in favor of busing. He was also effective in attacking Davis for receiving thousands of dollars in political donations from out-of-state groups, principally from New York City and Los Angeles. These groups favored mandatory federal programs that used busing to achieve school integration.[5]

McDonald won the primary in a surprise upset and was elected in November 1974 to the 94th United States Congress, serving Georgia's 7th congressional district, which included most of Atlanta's northwestern suburbs (including Marietta), where opposition to school busing was especially high. However, in the general election, J. Quincy Collins, Jr., an Air Force prisoner of war during the Vietnam War, running as a Republican, nearly defeated him, despite the poor performance of Republicans nationally that year due to the aftereffects of the Watergate scandal. McDonald, though, was re-elected four times with wide margins (including a 1976 rematch with Collins) and served from January 3, 1975, until his death, on September 1, 1983. His seat represented a contrast in political geography, as Republicans were successfully competing against moderate Democrats using the Southern strategy. Unlike many national Democrats, McDonald hewed to a consistently conservative line on issues such as foreign policy, defense spending, fiscal restraint, states rights, gun rights, and was pro-life, while mounting campaigns that successfully combined modern elements with a more traditional grassroots strategy. It paid off in the fall; while many of his fellow Democrats succumbed to Republican opponents or switched parties, McDonald managed to retain his seat.

McDonald, who considered himself a traditional Democrat "cut from the cloth of Jefferson and Jackson",[6] was known for his conservative views, even by Southern standards. Given his Old Right and Southern views, he was more conservative than the Republican Party. In fact, one scoring method published in the American Journal of Political Science[7] named him the second most conservative member of either chamber of Congress between 1937 and 2002 (behind only Ron Paul).[8] The American Conservative Union gave him a perfect score of 100 every year he was in the House of Representatives, except in 1978, when he scored a 95.[9] He also scored "perfect or near perfect ratings" on the congressional scorecards of the National Right to Life Committee, Gun Owners of America, and the American Security Council.[10] Referred to by The New American as "the leading anti-Communist in Congress",[10] McDonald admired Senator Joseph McCarthy[11] and was a member of the Joseph McCarthy Foundation.[3] He took the communist threat seriously and considered it an international conspiracy. An admirer of Austrian economics and a member of the Ludwig von Mises Institute,[3] he was an advocate of tight monetary policy in the late 1970s to get the economy out of stagflation, and advocated returning to the gold standard.[12] McDonald called the welfare state a "disaster"[13] and favored phasing control of the Great Society programs over to the states to operate and run.[14] He also favored cuts to foreign aid, saying, "To me, foreign aid is an area that you not only can cut but you could take a chainsaw to in terms of reductions."[14]

His staunch conservative views on social issues attracted controversy. For instance, McDonald sponsored amendments to stop government aid to homosexuals.[15] McDonald also co-sponsored a bill "expressing the sense of the Congress that homosexual acts and the class of individuals who advocate such conduct shall never receive special consideration or a protected status under law".[16] He advocated the use of the non-approved drug laetrile to treat patients in advanced stages of cancer[17] despite medical opinion that the promotion of laetrile to treat cancer was a canonical example of quackery.[18][19][20] McDonald also opposed the establishment of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day,[3][21] saying the FBI had evidence that King "was associated with and being manipulated by communists and secret communist agents".[22] However, he supported many African-American causes and was the prime mover in dedicating two statues in the US Congress Capital Rotunda-area, to prominent African American leaders, including George Washington Carver.

McDonald, a reported gun collector, and fire-arms enthusiast, and game hunter, allegedly had "about 200" guns at his official district residence.[23]

In 1975, Tom Anderson mentioned McDonald's name as a potential 1976 presidential candidate for the American Party. McDonald dismissed the idea, saying "I have enough to do right now representing the Seventh District in Congress."[24]

McDonald was frequently opposed by members of his own party, once remarking that "The national [Democratic] party is a bunch of kooks" but that he had "no problems" with Georgia or 7th District Democrats.[3] However, in 1978, the Seventh District Democratic Committee led by Chairman Ron Drake, voted, 10–8–1, to pass a resolution to "censure" McDonald "for the dishonorable and despicable act of calling himself a Democrat".[25] The main reason for the censure was McDonald's membership in the John Birch Society. Other reasons included: McDonald's support for denying there were implied powers in the U.S. Constitution, the claim that McDonald did not favor anti-monopoly laws, McDonald's lack of support for Jimmy Carter, and the claim that McDonald ran misleading advertisements.[25] McDonald's reply stated the censure was "illegal" under party rules, but that the action would probably help him at the polls: "It proves beyond any doubt to all my constituents in the Seventh District that I represent them and that I am not the puppet of a clique of liberal, disgruntled party bosses." He also felt the resolution would "badly split" the party and "make it much easier for other political parties to gain clout on the local level in future years".[6]

In 1979, with John Rees and Major General John K. Singlaub, McDonald founded the Western Goals Foundation. According to The Spokesman-Review, it was intended to "blunt subversion, terrorism, and communism" by filling the gap "created by the disbanding of the House Un-American Activities Committee and what [McDonald] considered to be the crippling of the FBI during the 1970s".[22] McDonald became the second president of the John Birch Society in 1983, succeeding Robert Welch.[22]

McDonald rarely spoke on the House floor, preferring to insert material into the Congressional Record.[22] These insertions typically dealt with foreign policy issues relating to the Soviet Union and domestic issues centered on the growth of non-Soviet and Soviet sponsored leftist subversion. A number of McDonald's insertions relating to the Socialist Workers Party were collected into a book, Trotskyism and Terror: The Strategy of Revolution, published in 1977.[26]

During his time in Congress, McDonald introduced over 150 bills, including legislation to:

- Repeal the Gun Control Act of 1968.

- Remove the limitation upon the amount of outside income a Social Security recipient may earn.

- Award honorary U.S. Citizenship to Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

- Invite Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to address a joint meeting of Congress.

- Prohibit Federal funds from being used to finance the purchase of American agricultural commodities by any Communist country.

- Create a select committee in the House of Representatives to conduct an investigation of human rights abuses in Southeast Asia by Communist forces.

- Repeal the FCC regulations against editorializing and support of political candidates by noncommercial educational broadcasting stations.

- Create a House Committee on Internal Security.

- Impeach UN Ambassador Andrew Young.

- Limit eligibility for appointment and admission to any United States service academy to men.

- Direct the Comptroller General of the United States to audit the gold held by the United States annually.

- Increase the national speed limit to 65 miles per hour (105 km/h) from the then-prevailing national speed limit of 55 miles per hour (89 km/h).

- Abolish the Federal Election Commission.

- Get the U.S. out of the United Nations.

- Place statues of Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver in the Capitol.

McDonald also introduced numerous bills to stop the making of loans and selling of arms to communist or communist-friendly regimes.

At the time of his death, McDonald was considering a run for President of the United States.[27]

Death

McDonald was invited to South Korea to attend a celebration of the 30th anniversary of the United States–South Korea Mutual Defense Treaty with three fellow members of Congress, Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, Senator Steve Symms of Idaho, and Representative Carroll Hubbard of Kentucky.[28] Due to bad weather on Sunday, August 28, 1983, McDonald's flight from Atlanta was diverted to Baltimore and when he finally arrived at JFK Airport in New York, he had missed his connection to South Korea by two or three minutes.[21] McDonald could have boarded a Pan Am Boeing 747 flight to Seoul, but he preferred the lower fares of Korean Air Lines and chose to wait for the next KAL flight two days later.[21] Simultaneously, Hubbard and Helms planned to meet with McDonald to discuss how to join McDonald on the KAL 007 flight. As the delays mounted, instead of joining McDonald, Hubbard at the last minute gave up on the trip, canceled his reservations, and accepted a Kentucky speaking engagement while Helms attempted to join McDonald but was also delayed.[29]

McDonald occupied an aisle seat, 02B in the first class section, when KAL 007 took off on August 31 at 12:24 AM local time, on a 3,400 miles (5,500 km) trip to Anchorage, Alaska for a scheduled stopover seven hours later.[21] The plane remained on the ground for an hour and a half during which it was refueled, reprovisioned, cleaned, and serviced.[21] The passengers were given the option of leaving the aircraft but McDonald remained on the plane, catching up on his sleep. Helms meanwhile had managed to arrive and invited McDonald to move onto his flight, KAL 015, but McDonald did not wish to be disturbed. With a fresh flight crew, KAL 007 took off at 4 AM local time for its scheduled non-stop flight over the Pacific to Seoul's Kimpo International Airport, a nearly 4,500 miles (7,200 km) flight that would take approximately eight hours.[21] On September 1, 1983, McDonald and the rest of the passengers and crew of KAL 007 were reportedly killed when Soviet fighters, under the command of Gen. Anatoly Kornukov, shot down KAL 007 near Moneron Island after the plane entered Soviet airspace.

The International Committee for the Rescue of KAL 007 Survivors, a group made up of some families of the victims of the shootdown, maintains that there is reason to believe that McDonald and others of Flight 007 survived the shootdown.[30] The committee corroborates this theory with claims that Soviet military communication and black box transcripts show a post-missile detonation flightpath at 5,000 meters (16,000 ft) for almost 5 minutes until the stricken aircraft was over the only land mass in the Tatar straits and within Soviet territorial waters, where it began a slow spiral descent.

This viewpoint has received some coverage in the conservative news agency Accuracy in Media and also the New American, the magazine of the John Birch Society.[31][32][33][34][35]

Aftermath

After McDonald's death, a special election was held to fill his seat in Congress. Former Governor Lester Maddox stated his intention to run for the seat if McDonald's widow, Kathy McDonald, did not.[36] Kathy McDonald did decide to run, but she lost to George "Buddy" Darden. Much of the congressional district McDonald represented would later be represented by Newt Gingrich.

Tribute

On March 18, 1998, the Georgia House of Representatives, "as an expression of gratitude for his able service to his country and defense of the US Constitution", passed a resolution naming the portion of Interstate 75, which runs from the Chattahoochee River northward to the Tennessee state line in his honor, the Larry McDonald Memorial Highway.

Quotations

- "[T]he drive of the Rockefellers and their allies is to create a one-world government, combining super-capitalism and Communism under the same tent, all under their control ... Do I mean conspiracy? Yes I do. I am convinced there is such a plot, international in scope, generations old in planning, and incredibly evil in intent."[37][38]

- (Speaking of Carroll Quigley, a history professor at Georgetown University:) "He says, Sure we've been working it, sure we've been collaborating with communism, yes we're working with global accommodation, yes, we're working for world government. But the only thing I object to, is that we've kept it a secret."[39]

- "I personally believe that we don't need a lot more laws, I think we've got far too many laws on the books now, that's part of the problem.... We don't need more government, more laws; we need a lot less. I'm up there [in Washington, D.C.], trying to dismantle a lot of this giant government.... When you 'pass a law' with the current attitude in the Congress what do you get in a law today? You get either more spending, or more taxes, or more controls.... Which do you want? Do you want more spending? I think we've got too much. Do you want more taxes? I think we're taxed too heavily now. Do you want more controls over your life? Does anybody say 'Hey look, I really believe the federal government needs to control me. I want to be a slave. Please tell me how to run every facet of my life.' I don't hear many people saying that. I think most people say 'I think it's time we get the government off our backs, and out of our pockets.'"[13]

- "The complexity of social organization does not change. Our technologically sophisticated industrial society is more complex than the agrarian society of America in the eighteenth century. In this regard, that was 'a simpler world'. But the complexities of politics (politics here meaning the science of governing) do not change much. The basic political problems confronting the Framers of our Constitution were as complex as our political problems today—perhaps more so, because they were striking off into the dangerous unknown, whereas all we need do is return to the fine highway we were once on."[40]

Quotes about McDonald

- "There is a real question in my mind that the Soviets may have actually murdered 269 passengers and crew on the Korean Air Lines Flight 007 in order to kill Larry McDonald." – Jerry Falwell, The Washington Post, September 2, 1983

- "He was the most principled man in Congress." – Ron Paul, The Philadelphia Inquirer

- "McDonald has fine credentials: a good education, a successful career as a urologist. But his views on issues are so far out, and his political skill so limited, that he has little impact." – Michael Barone, The Almanac of American Politics 1984

Bibliography

- Allen, Gary. The Rockefeller File. McDonald, Lawrence P. (introduction). Seal Beach, CA: '76 Press, 1976. ISBN 0-89245-001-0.

- McDonald, Lawrence Patton. We Hold These Truths: A Reverent Review of the U.S. Constitution. Seal Beach, CA: '76 Press, 1976. ISBN 0-89245-005-3.

- McDonald, Lawrence Patton. Trotskyism and Terror: The Strategy of Revolution. Washington, D.C.: ACU Education and Research Institute, 1977.

See also

- Boll weevil (politics)

- John G. Schmitz

- John Rarick

- United States Congress members killed or wounded in office

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 St. John, Jeffrey (1985-09-30), "Essay on Character: Lawrence Patton McDonald (1935–1983)", The New American, archived from the original on 2007-09-27, retrieved 2009-08-24

- 1 2 3 4 "McDONALD, Lawrence Patton". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Willis, Maggie (1983-08-28), "Wearing Many Hats: Congressman Fills Roles in Various Organizations", The Marietta Daily Journal, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ International Committee for the Rescue of KAL 007 Survivors, The. "Lawrence 'Larry' Patton McDonald". March 10, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ↑ McDonald, Larry (1974-07-09), "Where I Stand (advertisement)", Rome News-Tribune, retrieved 2009-08-26

- 1 2 "Action to aid him but hurt party – McDonald", Rome News-Tribune, 1978-02-08, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ Poole, Keith T. (July 1998), "Estimating a Basic Space From A Set of Issue Scales", American Journal of Political Science, Midwest Political Science Association, 42 (3): 954–993, doi:10.2307/2991737, JSTOR 2991737, retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ↑ Poole, Keith T. (2004-10-13). "Is John Kerry a Liberal?". Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ ACU Ratings of Congress: House Ratings: 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- 1 2 "Remembering Larry McDonald", The New American, 2003-09-08, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ McDonald, Larry P. (1981), Remarks of the Honorable Larry P. McDonald of Georgia: On the occasion of the 24th annual memorial services commemorating the death of U.S. Senator Joseph Raymond McCarthy, Senator Joseph R. McCarthy Educational Foundation

- ↑ "Five Myths About the Gold Standard" by Rep. Larry McDonald and Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas). Congressional Record, Vol. 127, No. 28; February 23, 1981. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- 1 2 "Rep. Larry McDonald explains why Congress needs to stop passing laws" on YouTube. YouTube. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- 1 2 Royal, David (1982-08-20), "7th District Race for U.S. Congress: Incumbent Larry McDonald cites 'favorable record'", Rome News-Tribune, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ "H.Con.Res.29". congress.org. Library of Congress.

- ↑ "H.Con.Res.29". congress.gov. Library of Congress.

- ↑ "H.R.4045 - 96th Congress (1979-1980)". congress.gov. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Herbert V (May 1979). "Laetrile: the cult of cyanide. Promoting poison for profit". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 32 (5): 1121–58. PMID 219680.

- ↑ Lerner IJ (February 1984). "The whys of cancer quackery". Cancer. 53 (3 Suppl): 815–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3+<815::AID-CNCR2820531334>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 6362828.

- ↑ Nightingale SL (1984). "Laetrile: the regulatory challenge of an unproven remedy". Public Health Rep. 99 (4): 333–8. PMC 1424606

. PMID 6431478.

. PMID 6431478. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wilkes Jr., Donald E. (2003-09-03), "The Death Flight of Larry McDonald", Flagpole Magazine, p. 7, archived from the original on 2012-03-14, retrieved 2009-08-24

- 1 2 3 4 "McDonald's peers note tragic irony", The Spokesman-Review, 1983-09-02, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ "Congressman Reportedly Helped to Stockpile Guns", The New York Times, p. 18, 1977-03-30, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ "McDonald cool to Ford's address", Rome News-Tribune, 1975-03-13, retrieved 2009-08-26

- 1 2 "Seventh District Democratic panelist condemns Rep. Larry McDonald's membership in John Birch Society", Rome News-Tribune, 1978-02-08, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ Evans, M. Stanton (1977). Introduction. Trotskyism and Terror: The Strategy of Revolution. By Larry McDonald. Washington, D.C.: ACU Education and Research Institute. pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Ruppert, Michael C. (2002-01-02). "A War in the Planning for Four Years: How Stupid Do They Think We Are?". From The Wilderness Publications. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ Johnson, R. W. (1986), Shootdown: Flight 007 and the American Connection, New York, N.Y.: Viking Penguin, pp. 3–4

- ↑ Farber, Stephen (1988-11-27), "TELEVISION; Why Sparks Flew in Retelling the Tale of Flight 007", The New York Times, retrieved 2009-08-24

- ↑ "Rescue 007 Home". Rescue007.org. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Irvine, Reed (November 1, 2001). "Let's ask Putin". Accuracy in Media. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Irvine, Reed (December 6, 2001). "Put it to Putin". Accuracy in Media.

- ↑ Irvine, Reed (November 16, 2001). "Questions for President Putin". Accuracy in Media. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Lee, Robert W. (September 10, 1991). "KAL 007 Remembered: The Questions Remain Unanswered". The New American. John Birch Society.

- ↑ Mass, Warren (September 1, 2008). "KAL flight 007 remembered". The New American. John Birch Society. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ "Maddox Says He May Seek McDonald's Seat in House", The Miami Herald, 1983-09-08, retrieved 2009-08-26

- ↑ McDonald, Lawrence P. Introduction. The Rockefeller File. By Gary Allen. Seal Beach, CA: '76 Press, 1976. ISBN 0-89245-001-0.

- ↑ "Quotes by Pat Buchanan and Others on the New World Order". Archived from the original on 2007-10-10. Retrieved 2007-10-10.. The Internet Brigade. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ "Larry McDonald on the NWO May 1983PT2" on YouTube. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ McDonald, Lawrence Patton. We Hold These Truths: A Reverent Review of the U.S. Constitution. Seal Beach, CA: '76 Press, 1976, p. 13.

External links

- United States Congress. "Larry McDonald (id: M000413)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- "KAL Flight 007 Remembered", by Warren Mass, The New American, September 8, 2008

- "Unresolved Questions Surround KAL 007", by James Heiser, The New American, September 1, 2009

- Larry McDonald on Crossfire in 1983

- "KAL 007 Mystery", Timothy Maier, Insight Magazine at the Wayback Machine (archived September 19, 2001)

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John W. Davis |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 7th congressional district January 3, 1975 – September 1, 1983 |

Succeeded by George Darden |

| Other offices | ||

| Preceded by Robert W. Welch, Jr. |

President of the John Birch Society 1983 |

Succeeded by Robert W. Welch, Jr. |