Nynorsk

| Norwegian Nynorsk | |

|---|---|

| nynorsk | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈnyːnɔʂk] or [ˈnyːnɔʁsk] |

| Native to | Norway |

Native speakers |

None (written only) |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early forms |

Old West Norse

|

Standard forms |

Nynorsk (official)

Høgnorsk (unofficial)

|

| Latin (Norwegian alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Norway Nordic Council |

| Regulated by | Norwegian Language Council |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

nn |

| ISO 639-2 |

nno |

| ISO 639-3 |

nno |

| Glottolog | None |

| Linguasphere |

52-AAA-ba to -be |

Nynorsk, New Norwegian, Neo-Norwegian, or New Norse[1] is an official written standard for the Norwegian language, alongside Bokmål. The language standard was originally created by Ivar Aasen during the mid-19th century, to provide a Norwegian alternative to the Danish language, which was commonly written in Norway at the time. The official standard of Nynorsk has since been significantly altered. A minor purist fraction of the Nynorsk populace have stayed firm with the Aasen norm, which is known as Høgnorsk (English: High Norwegian, analogous to High German).

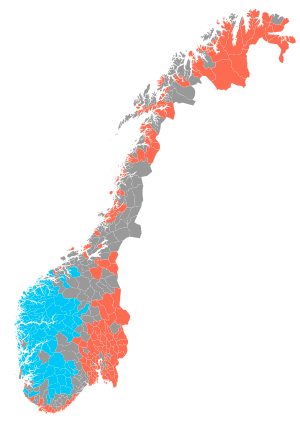

In local communities, 26% (113 of 428) of the Norwegian municipalities have declared Nynorsk as their official language form, and these municipalities account for about 12% of Norwegians. Of the remaining 74% of the municipalities, half are neutral and half have adopted Bokmål as their official language form.[2] Four of the 19 counties, Rogaland, Hordaland, Sogn og Fjordane and Møre og Romsdal, have Nynorsk as their official language form. These four together comprise the region of Western Norway.[3]

The Language Council of Norway recommends the name Norwegian Nynorsk when referring to this standard in English.

Writing and speech

Spoken Norwegian, Swedish and Danish form a continuum of dialects and sociolects that are somewhat mutually intelligible. Nynorsk is the smallest of the four written standards in Scandinavia.

Nynorsk is found in all the same types of places and for the same uses (newspapers, commercial products, computer programs, etc.) as the other Scandinavian standard languages. Bokmål has a much larger basis in urban speech, especially that found in the eastern part of Southern Norway.[4] However, most Norwegians do not speak the so-called standard østnorsk, "standard eastern Norwegian", but rather other Norwegian dialects. As such, Nynorsk is not a minority language, though it shares many of the problems that minority languages face.

Each municipality and county can declare one of the two languages as its official language, or it can remain "language neutral". In Norway as a total, 26% of the municipalities (114 in all) making up 12% of the population have declared Nynorsk as their official language, while 36% (158) have chosen Bokmål and another 36% (157) have stayed Neutral. At least 128 of the "Neutral" municipalities are in areas where Bokmål is the prevailing form and pupils are taught in Bokmål. As for counties, three have declared Nynorsk: Hordaland, Møre og Romsdal and Sogn og Fjordane. Two have declared Bokmål: these are Østfold and Vestfold. All other counties are officially language neutral.

The main language used in primary schools normally follows the official language of its municipality, and is decided by referendum within the local school district. The number of school districts and pupils using primarily Nynorsk has decreased from its height in the 1940s, even in Nynorsk municipalities. As of 2011, 12.8% of pupils in primary school are taught Nynorsk as their primary language.[3]

The prevailing regions for Nynorsk are the rural areas of the western counties of Rogaland, Hordaland, Sogn og Fjordane and Møre og Romsdal, in addition to the western/northern parts of Oppland, Buskerud, Telemark, Aust- and Vest-Agder, where an estimated 90% of the population writes Nynorsk. Usage of Nynorsk in the rest of Norway, including the major cities and urban areas in the above stated areas, is scarce. In Sogn og Fjordane county and the Sunnmøre region of Møre og Romsdal, all municipalities have stated Nynorsk as the official language, the only exception being Ålesund, which remains neutral. In Hordaland, all municipalities except three have declared Nynorsk as the official language.

Ivar Aasen's work

In 1749, Erik Pontoppidan released a comprehensive dictionary of Norwegian words that were incomprehensible to Danish people, Glossarium Norvagicum Eller Forsøg paa en Samling Af saadanne rare Norske Ord Som gemeenlig ikke forstaaes af Danske Folk, Tilligemed en Fortegnelse paa Norske Mænds og Qvinders Navne.[5] Nevertheless, it is generally acknowledged that the first systematic study of the Norwegian language was made by Ivar Aasen in the mid 19th century. After the dissolution of Denmark–Norway and the establishment of the union between Sweden and Norway in 1814, Norwegians considered that neither Danish, by now a foreign language, nor by any means Swedish, were suitable written norms for Norwegian affairs. The linguist Knud Knudsen proposed a gradual Norwegianisation of Danish. Ivar Aasen, however, favoured a more radical approach, based on the principle that people living in the Norwegian countryside, who made up the vast majority of the populace, should be regarded as more Norwegian than upper-middle class city-dwellers, who for centuries had been substantially influenced by the Danish language and culture.[6] This idea was not unique to Aasen, and can be seen in the wider context of Norwegian romantic nationalism. In the 1840s Aasen traveled across rural Norway and studied its dialects. In 1848 and 1850 he published the first Norwegian grammar and dictionary, respectively, which described a standard that Aasen called Landsmål. New versions detailing the written standard were published in 1864 and 1873, and in the 20th century by Olav Beito in 1970.[7]

During the same period, Venceslaus Ulricus Hammershaimb standardised the orthography of the Faroese language. Spoken Faroese is closely related to Landsmål and dialects in Norway proper, and Lucas Debes and Peder Hansen Resen classified the Faroese tongue as Norwegian in the late 17th century.[8] Ultimately, however, Faroese was established as a separate language.

Aasen's work is based on the idea that Norwegian dialects had a common structure that made them a separate language alongside Danish and Swedish. The central point for Aasen therefore became to find and show the structural dependencies between the dialects. In order to abstract this structure from the variety of dialects, he developed some basic criteria, which he called the most perfect form. He defined this form as the one that best showed the connection to related words, with similar words, and with the forms in Old Norwegian. No single dialect had all the perfect forms, each dialect had preserved different aspects and parts of the language. Through such a systematic approach, one could arrive at a uniting expression for all Norwegian dialects, what Aasen called the fundamental dialect, and Einar Haugen has called Proto-Norwegian.

The idea that the study should end up in a new written language marked his work from the beginning. A fundamental idea for Aasen was that the fundamental dialect should be Modern Norwegian, not Old Norwegian or Old Norse. Therefore, he did not include grammatical categories which were extinct in all dialects. At the same time, the categories that were inherited from the old language and were still present in some dialects should be represented in the written standard. Haugen has used the word reconstruction rather than construction about this work.

Nynorsk has been revised and reformed a number of times since Aasen's original publications. These reforms were intended to close the gap between Nynorsk and Bokmål, as policymakers sought to create one unified Norwegian language, samnorsk. This goal has now been abandoned.[9] Høgnorsk is a present-day alternative for purists who prefer Aasen's original norm. Ivar Aasen-sambandet is an umbrella organization of associations and individuals promoting the use of Høgnorsk, whereas Noregs Mållag and Norsk Målungdom advocate the use of Nynorsk in general.

Conflict

From the outset, Nynorsk was met with resistance. With the advent and growth of mass media, exposure to the standard languages has increased, and Bokmål's dominant position has come to define what is commonly regarded as "normal". This may explain why negative attitudes toward Nynorsk are common, as is seen with many minority languages. This is especially prominent in school, which is the place most Bokmål-using Norwegians first and most extensively need to relate to the language.

Some critics of Nynorsk have been quite outspoken about their views. For instance, during the 2005 election, the Norwegian Young Conservatives made an advertisement that included a scene where a copy of the Nynorsk dictionary was burned. After strong reactions to this book burning, they chose not to show it.[10]

Grammar

Nynorsk is a North-Germanic language, close in form to the other form of written Norwegian (Bokmål), and Icelandic. It thus has North-Germanic grammatical forms, and Nynorsk grammar may be compared to Bokmål Norwegian, but it is closer in grammar to Old West Norse than Bokmål, which was influenced by Danish much more heavily than Nynorsk was.

Three genders

Genders are inherent properties of nouns, and each gender has its own forms of inflection.

Standard Nynorsk and, with the exception of the Bergen dialect (Bergensk), all dialects have three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. The situation is slightly more complicated in Bokmål, which has inherited the Danish two-gender system. Written Danish only retains the neuter and the common gender. Though the common gender took what used to be the feminine inflections in Danish, it matches the masculine inflections in Norwegian. The Norwegianization in the 20th century brought the three-gender system into Bokmål, but the process was never completed. In Nynorsk these are important distinctions, in contrast to Bokmål, in which all feminine words may also become masculine (due to the incomplete transition to a three-gender system) and inflect using its forms, and indeed a feminine word may be seen in both forms, for example boka or boken (“the book”). The feminine forms of other words usually become inflected by the gender of the noun they belong to, such as ei (“a(n)”), inga (“no”, “none”) and lita (“small”), are optional too (masculine is used when feminine is not). This means that en liten stjerne – stjernen (“a small star – the star”, only masculine forms) and ei lita stjerne – stjerna (only feminine forms) both are correct Bokmål, as well as every possible combination: en liten stjerne – stjerna, ei liten stjerne – stjerna or even ei lita stjerne – stjernen. Choosing either two or three genders throughout the whole text is not a requirement either, so one may choose to write tida (“the time” f) and boken (“the book” m) in the same work.

In Nynorsk (unlike Bokmål), masculine and feminine nouns are differentiated not only in the singular definitive form (in which the noun takes a suffix to indicate "the"), but also in the plural forms (which they would not be in Bokmål), for example:

| Singular | Definitive singular | Plural | Definitive plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| masculine: | |||

| rev | reven | revar | revane |

| fox | the fox | foxes | the foxes |

| feminine: | |||

| løve | løva | løver | løvene |

| lion | the lion | lions | the lions |

| neuter: | |||

| hus | huset | hus | husa |

| house | the house | houses | the houses |

This differentiation is expressed in distinctive ways in the dialects, for example reva/revan(e) and løve/løven(e), revær/revane and løver/løvene or rever/reva and løver/løvene.

Inflection

However, a grammatical gender is not characterised by noun inflection alone; each gender can have further inflectional forms. That is, gender can determine the inflection of other parts of speech which agree grammatically with a noun. This concerns determiners and adjectives. For example:

| Masculine example: | ein liten rev | min eigen rev | a small fox | my own fox |

| Feminine example: | ei lita løve | mi eiga løve | a small lion | my own lion |

Usage changes too from dialect to dialect, for example en liten rev, min egen rev but e lita løve, mi ega løve or ein liten rev, min eigen rev men ei liti løve, mi eigi løve.

T as final sound

One of the past participle and the preterite verb ending in Bokmål is -et. Aasen originally included these t's in his Landsmål norms, but since these are silent in the dialects, it was struck out in the first officially issued specification of Nynorsk of 1901.

Examples may compare the Bokmål forms skrevet ('written', past participle) and hoppet ('jumped', both past tense and past participle), which in written Nynorsk are skrive or skrivi (Landsmål skrivet) and hoppa (Landsmål hoppat). The form hoppa is also permitted in Bokmål.

Other examples from other classes of words include the neuter singular form anna of annan ('different', with more meanings) which was spelled annat in Landsmål, and the neuter singular form ope of open ('open') which originally was spelled opet. Bokmål, in comparison, still retains these t's through the equivalent forms annet and åpent.

Word forms compared with Bokmål Norwegian

Many words in Nynorsk are similar to their equivalents in Bokmål, with differing form, for example:

| Nynorsk | Bokmål | other dialect forms | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| eg | jeg (pronounced jei) | eg, æg, e, æ, ei, i, je, jæ | I |

| ikkje | ikke | ikkje, inte, ente, itte, itj, ikkji | not |

The distinction between Bokmål and Nynorsk is that while Bokmål has for the most part derived its forms from the written Danish language or the common Danish-Norwegian speech, Nynorsk has its orthographical standards from Aasen's reconstructed "base dialect", which are intended to represent the distinctive dialectical forms.

See also

- Norwegian dialects

- Modern Norwegian

- Spynorsk mordliste, a term used by opponents to mock Nynorsk

References

- ↑ Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1 ed.). Random House, Inc.;

- ↑ "Ivar Aasen-tunet" (in Norwegian Nynorsk). Nynorsk kultursentrum. 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- 1 2 "Språkstatistikk – nokre nøkkeltal for norsk". Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Kristoffersen, Gjert (2000). The Phonology of Norwegian. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-823765-5.

- ↑ "Glossarium Norvagicum eller Forsøg paa en Samling af saadanne rare Norske Ord". runeberg.org. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ↑ Jahr, E.H., The fate of Samnorsk: a social dialect experiment in language planning. In: Clyne, M.G., 1997, Undoing and redoing corpus planning. De Gruyter, Berlin.

- ↑ Venås, Kjell. 2009. Beito, Olav T. In: Stammerjohann, Harro (ed.), Lexicon Grammaticorum: A Bio-Bibliographical Companion to the History of Linguistics p. 126. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- ↑ Sandøy, H., Frå tre dialektar til tre språk. In: Gunnstein Akselberg og Edit Bugge (red.), Vestnordisk språkkontakt gjennom 1200 år. Tórshavn, Fróðskapur, 2011, pp. 19-38.

- ↑ Jahr, 1997.

- ↑ "Brenner nynorsk-bok i tønne". Retrieved 2008-02-02.

External links

| Norwegian Nynorsk edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Noregs Mållag Noregs Mållag is the major organization promoting Nynorsk.

- Norsk Målungdom Norsk Målungdom is Noregs Mållag's youth organization.

- Ivar Aasen-tunet The Ivar Aasen Centre is a national centre for documenting and experiencing the Nynorsk written culture, and the only museum in the country devoted to Ivar Aasen's life and work.

- Norsk programvareblogg computer programmes in Nynorsk.

- Sidemålsrapport – report (in Bokmål) on the state of Nynorsk and Bokmål in Norwegian secondary schools.