Lacrimal gland

| Lacrimal gland | |

|---|---|

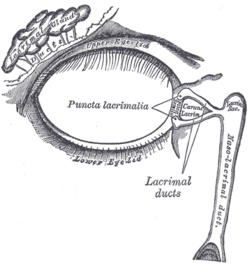

Lacrimal apparatus of the right eye. The lacrimal gland is to the upper left. The right side of the picture is towards the nose. | |

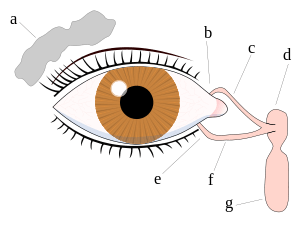

Tear system. a = lacrimal gland b = superior lacrimal punctum c = superior lacrimal canal d = lacrimal sac e = inferior lacrimal punctum f = inferior lacrimal canal g = nasolacrimal canal | |

| Details | |

| Artery | lacrimal artery |

| Nerve | lacrimal nerve, Zygomatic nerve via Communicating branch, greater petrosal nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandula lacrimalis |

| TA | A15.2.07.057 |

| FMA | 59101 |

The lacrimal glands are paired, almond-shaped glands, one for each eye, that secrete the aqueous layer of the tear film. They are situated in the upper lateral region of each orbit, in the lacrimal fossa of the orbit formed by the frontal bone.[1] Inflammation of the lacrimal glands is called dacryoadenitis. The lacrimal gland produces tears which then flow into canals that connect to the lacrimal sac. From that sac, the tears drain through the lacrimal duct into the nose.

Anatomists divide the gland into two sections. The smaller palpebral portion lies close to the eye, along the inner surface of the eyelid; if the upper eyelid is everted, the palpebral portion can be seen.

The orbital portion contains fine interlobular ducts that unite to form 3–5 main excretory ducts, joining 5–7 ducts in the palpebral portion before the secreted fluid may enter on the surface of the eye. Tears secreted collect in the fornix conjunctiva of the upper lid, and pass over the eye surface to the lacrimal puncta, small holes found at the inner corner of the eyelids. These pass the tears through the lacrimal canaliculi on to the lacrimal sac, in turn to the nasolacrimal duct, which dumps them out into the nose.[2]

Microanatomy

The lacrimal gland is a compound tubuloacinar gland, it is made up of many lobules separated by connective tissue, each lobule contains many acini. The acini contain only serous cells and produce a watery serous secretion.

Each acinus consists of a grape-like mass of lacrimal gland cells with their apices pointed to a central lumen.

The central lumen of many of the units converge to form intralobular ducts, and then they unite to from interlobular ducts. The gland lacks striated ducts.

Innervation

The parasympathetic nerve supply originates from the lacrimatory nucleus of the facial nerve in the pons. From the pons nucleus preganglionic parasympathetic fibres run in the nervus intermedius (small sensory root of facial nerve) to the geniculate ganglion but they do not synapse there. Then, from the geniculate ganglion, the preganglionic fibres run in the greater petrosal nerve (a branch of the facial nerve) which carries the parasympathetic secretomotor fibers through the foramen lacerum, where it joins the deep petrosal nerve (which contains postganglionic sympathetic fibers from the superior cervical ganglion) to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal (vidian nerve) which then traverses through the pterygoid canal to the pterygopalatine ganglion. Here, the fibers synapse and postganglionic fibers join the fibers of the maxillary nerve. In the pterygopalatine fossa itself, the parasympathetic secretomotor fibers branch off with the zygomatic nerve and then branch off again, joining with the lacrimal branch of the ophthalmic division of CN V, which supplies sensory innervation to the lacrimal gland along with the eyelid and conjunctiva.

The sympathetic postganglionic fibers originate from the superior cervical ganglion. They traverse as a periarteriolar plexus with the internal carotid artery, before they merge and form the deep petrosal nerve, which joins the greater petrosal nerve in the pterygoid canal. Together, greater petrosal and deep petrosal nerves form the nerve of the pterygoid canal (vidian nerve) and they reach the pterygopalatine ganglion in the pterygopalatine fossa. In contrast to their parasympathetic counterparts, sympathetic fibers do not synapse in the pterygopalatine ganglion, having done so already in the sympathetic trunk. However, they continue to course with the parasympathetic fibers innervating the lacrimal gland.

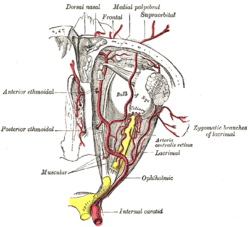

Blood supply

The lacrimal artery, derived from the ophthalmic artery supplies the lacrimal gland. Venous blood returns via the superior ophthalmic vein.

Lymphatic drainage

The glands drain into the superficial parotid lymph nodes.[3]

Nerve supply

The lacrimal nerve, derived from the ophthalmic nerve, supplies the sensory component of the lacrimal gland. The greater petrosal nerve, derived from the facial nerve, supplies the parasympathetic autonomic component of the lacrimal gland. The greater petrosal nerve traverses alongside branches of the V1 and V2 divisions of the trigeminal nerve. The proximity of the greater petrosal nerve to branches of the trigeminal nerve explains the phenomenon of lesions to the trigeminal nerve causing impaired lacrimation although the trigeminal nerve does not supply the lacrimal gland.

Pathology

In contrast to the normal moisture of the eyes or even crying, there can be persistent dryness, scratching, and burning in the eyes, which are signs of dry eye syndrome (DES) or keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS). With this syndrome, the lacrimal glands produce less lacrimal fluid, which mainly occurs with ageing or certain medications. A thin strip of filter paper (placed at the edge of the eye) the Schirmer test, can be used to determine the level of dryness of the eye. Many medications or diseases that cause dry eye syndrome can also cause hyposalivation with xerostomia. Treatment varies according to aetiology and includes avoidance of exacerbating factors, tear stimulation and supplementation, increasing tear retention, eyelid cleansing, and treatment of eye inflammation.[3]

In addition, the following can be associated with lacrimal gland pathology:

Additional images

The ophthalmic artery and its branches.

The ophthalmic artery and its branches. Nerves of the orbit. Seen from above.

Nerves of the orbit. Seen from above. Sympathetic connections of the sphenopalatine and superior cervical ganglia.

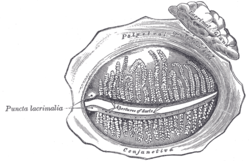

Sympathetic connections of the sphenopalatine and superior cervical ganglia. The tarsal glands, etc., seen from the inner surface of the eyelids.

The tarsal glands, etc., seen from the inner surface of the eyelids. Alveoli of lacrimal gland.

Alveoli of lacrimal gland.- Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

- Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

- Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

- Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

- Extrinsic eye muscle. Nerves of orbita. Deep dissection.

See also

References

- ↑ Clinically Oriented Anatomy, Moore, Dalley & Agur.

- ↑ "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. Encyclopædia Britannica 2010 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2010

- 1 2 Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, page 153.

External links

- lesson3 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (orbit2)

- Diseases of the lacrimal gland at http://www.academy.org.uk/lectures/barnard11.htm