Labadists

| Part of the series on 17th-century scholasticism | |

| |

| Title page of the Calov Bible | |

| Background | |

|---|---|

|

Protestant Reformation | |

| 17th-century scholastics | |

|

Second scholasticism of the Jesuits | |

| Reactions within Christianity | |

|

Labadists against the Jesuits | |

| Reactions within philosophy | |

|

Modernists against Roman Catholics | |

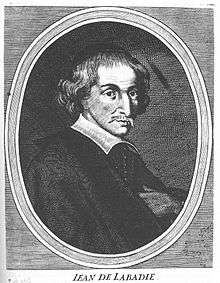

The Labadists were a 17th-century Protestant religious community movement founded by Jean de Labadie (1610–1674), a French pietist. The movement derived its name from that of its founder.

Jean de Labadie’s life

Jean de Labadie (1610–1674) came from an area near Bordeaux. In his early life he was a Roman Catholic and a Jesuit. However, at that time, the Jesuits were wary of overt spiritual manifestations,[1] so Labadie, who himself experienced frequent visions and inner enlightenment, found himself dissatisfied and left the order in 1639.

He had fleeting links with the Oratoire, then Jansenism (on occasions staying with the solitaries of Port-Royal, who received him at the time but later sought to dissociate themselves from him). He was a parish priest and evangelist in the southern French dioceses of Toulouse and Bazas, preaching social righteousness, new birth, and separation from worldliness. His promotion of inner piety and personal spiritual experiences brought opposition and threats from the religious establishment.

Eventually, frustrated with Roman Catholicism, Labadie became a Calvinist at Montauban in 1650. In that city and then in the principality of Orange he championed the rights of the Protestant minority in the face of increasing legislation against them by Louis XIV (which would culminate in 1685 with the Edict of Fontainebleau). Labadie then moved to Geneva, where he was hailed as ‘a second Calvin’.[2] Here he began to doubt the lasting validity of established Christianity. He held house groups for Bible-study and fellowship, for which he was censured.

In 1666 Labadie and several disciples moved to the Netherlands, to the French-speaking Walloon congregation of Middelburg. Here his pattern continued: seeking to promote active church renewal through practical discipleship, study of the Bible, house meetings, and much else that was novel for the Reformed Church at that time. Here too he made contact with leading figures of the spiritual and reformatory circles of the day, such as Jan Amos Comenius, and Antoinette Bourignon.

With a broad-mindedness unusual for the period, Labadie was gracious and cautiously welcoming towards the move of repentance and new zeal among many Jews in a Messianic movement around Sabbatai Sevi in 1667.[3]

At length, in 1669, at 59 years of age, Labadie broke away from all established denominations and began a Christian community at Amsterdam. In three adjoining houses lived a core of some sixty adherents to Labadie’s teaching. They shared possessions after the pattern of the Church as described in the New Testament book of Acts.[4] Persecution forced them to leave after only a year, and they moved to Herford in Germany. Here the community became more firmly established until war forced them to move to Altona (then in Denmark, now a suburb of Hamburg), where Labadie died in 1674.

Labadie's most influential writing was La Réformation de l'Eglise par le Pastorat (1667).

The Labadist community

In the Labadist community there were craftsmen, who generated income, although as many men as possible were sent on outreach to neighbouring towns. Children were tutored communally. The women had traditional roles as homemakers. A printing press was set up, disseminating many writings by Labadie and his colleagues. Curiously, the best known of all Labadist writings was not Labadie’s but Anna van Schurman’s, who wrote a justification of her renunciation of fame and reputation to live in Christian community.[5] Van Schurman was noted in her day as ‘The Star of Utrecht’ and widely admired for her talents: she spoke and wrote five languages, produced an Ethiopic dictionary, played several instruments, engraved glass, painted, embroidered, and wrote poetry. At the age of 62 she gave up everything and joined the Labadists.[6]

After Labadie’s death, his followers returned to the Netherlands, where they set up a community in a stately home – Walta Castle – at Wieuwerd in Friesland, which belonged to three sisters Van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck, who were his adherents. Here printing and many other occupations continued, including farming and milling. One member, Hendrik van Deventer,[7] skilled in chemistry and medicine, set up a laboratory at the house and treated many people, including Christian V, the King of Denmark. He is now remembered as one of the Netherlands' pioneering obstetricians.

Several noted visitors have left their accounts of visits to the Labadist community. One was Sophie of Hanover, mother of King George I of Great Britain; another was William Penn, the Quaker pioneer, who gave his name to the US state of Pennsylvania; a third was the English philosopher John Locke.[8]

Several Reformed pastors left their parishes to live in community at Wieuwerd. At its peak, the community numbered around 600 with many more adherents further afield. Visitors came from England, Italy, Poland and elsewhere, but not all approved of the strict discipline. Those of arrogant disposition were given the most menial of jobs. Fussiness in matters or food was overcome since all were expected to eat what was put in front of them.

Daughter communities were set up in the New World. La Providence, a daughter colony on the Commewijne River in Surinam, proved unsuccessful. The Labadists were unable to cope with jungle diseases, and supplies from the Netherlands were often intercepted by pirates.[9] The noted entomological artist, Maria Sybilla Merian, who had lived in the Labadist colony in Friesland for some years, went to Surinam in 1700 and drew several plates for her classic Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium on the Labadist plantation of La Providence.[10]

Bohemia Manor

The mother colony in Friesland sent two envoys, Jasper Danckaerts and Peter Schlüter (or Sluyter), to purchase land for a colony. Danckaerts, an experienced seafarer, kept a journal which has survived and has been published.[11] It is a valuable early account of life in colonial New Netherland (later New York), on the Chesapeake and the Delaware in 1679-80 and includes several hand drawings and maps.

Danckaerts and Schlüter met the son of Augustine Herman, a successful Maryland businessman, in New York and he introduced them to his father in 1679. Herman was impressed with the men and their group. Initially Herman did not want to grant land to them, only permit Labadist settlement, but in 1683, he conveyed a tract of 3,750 acres (15 km²) on his land Bohemia Manor in Cecil County, Maryland to them because of legal issues.[12] The group established a colony which grew rapidly to between 100-200 members.[13]

In the 1690s a gradual decline set in and finally the practice of communal sharing was suspended. From that moment on the Labadists dwindled, both in Maryland, which ceased to exist after 1720,[12] and in Friesland they had died out by 1730.

Key beliefs of the Labadists

The Labadists held to the beliefs and traditions of their founder, Labadie. Chiefly these were:

- The true Church of Jesus Christ is composed solely of those ‘born again’ or ‘elect’; habitual churchgoing while not knowing God personally is nugatory

- The true Church is also ‘not of this world’; this affects all of life, including clothing (Labadists had their own dress for women, known in Dutch as a ‘borstrok’ similar to a nun’s habit).

- Even so, the Church is always in need of reform, and this should start at the top, with the priests or pastors.

- Knowing God is not through set religious laws but through personal prayer and mystical devotion; the heart should be warmed through contact with divine love.

- All members are priests and can bring words of edification in church gatherings, which Labadie equated with New Testament ‘prophetic ministry’. To facilitate this, home groups are the best forum.

- The Holy Communion is only for the truly committed (in Labadist parlance the ‘elect’).

- Self-denial, in particular fasting, is good for the soul.

- Worldly vanities are to be eschewed and personal wealth shared in the community brotherhood.

- An Augustinian (specifically Jansenist) belief in predestination.

- Marriage must be ‘in the Lord’; a believer can justifiably separate from an unconverted partner in order to follow God’s call to his work (in Labadist jargon, ‘the Lord’s work’ meant their own community lifestyle).[2]

Legacy, influence and parallels

William Penn records in his journal a meeting with the Labadists in 1677, which gives an insight into the reasons why these people chose to live a communal lifestyle. Labadie’s widow, Lucia, testified to Penn about her younger days in which she had mourned the insipid state of the Christianity which she saw around her:

If God would make known to me his way, I would trample upon all the pride and glory of the world. ...O the pride, O the lusts, O the vain pleasures in which Christians live! Can this be the way to Heaven? ...Are these the followers of Christ? O God, where is Thy little flock? Where is Thy little family, that will live entirely to Thee, that will follow Thee? Make me one of that number.

Hearing Labadie’s teachings, she was convinced of her need to be joined in community living with her fellow believers.[14]

Labadie’s approach to Christian spirituality, but not his communitarian approach with its separation from mainstream churches, was paralleled in the Pietist movement in Germany. Many of its leaders, such as Philipp Jakob Spener, approved Labadie’s stance but preferred for their own part to trust in the established structures.

Some Pietist community enterprises did, however, arise. August Francke, professor at Halle University, founded there an orphanage (the Waisenhaus) in 1696, to be run along Christian communitarian lines, with equality and sharing of goods. This caused a stir and was famed abroad. Its example inspired in George Whitefield, the English preacher and revivalist, a yearning for a similar foundation which eventually came to being in America.

Labadie's Works

Labadie's most influential writing was The Reform of the Church Through the Pastorate (1667).

- Introduction à la piété dans les Mystères, Paroles et ceremonies de la Messe, Amiens, 1642.

- Odes sacrées sur le Très-adorable et auguste Mystère du S. Sacrement de l'Autel, Amiens, 1642.

- Traité de la Solitude chrestienne, ou la vie retirée du siècle, Paris, 1645.

- Déclaration de Jean de Labadie, cy-devant prestre, predicateur et chanoine d'Amiens, contenant les raisons qui l'ont obligé à quitter la communion de l'Eglise Romaine pour se ranger à celle de l'Eglise Réformée, Montauban, 1650.

- Lettre de Jean de Labadie à ses amis de la Communion Romaine touchant sa Declaration, Montauban, 1651.

- Les Elevations d'esprit à Dieu, ou Contemplations fort instruisantes sur les plus grands Mysteres de la Foy, Montauban, 1651.

- Les Entretiens d'esprit durant le jour; ou Reflexions importantes sur la vie humaine, ...sur le Christianisme,...sur le besoin de la Reformation de ses Mœurs, Montauban, 1651.

- Le Bon Usage de l'Eucharistie, Montauban, 1656.

- Practique des Oraisons, mentale et vocale..., Montauban, 1656.

- Recueil de quelques Maximes importantes de Doctrine, de Conduite et de Pieté Chrestienne, Montauban, 1657 (puis Genève, 1659).

- Les Saintes Décades de Quatrains de Pieté Chretienne touchant à la connoissance de Dieu, son honneur, son amour et l'union de l'âme avec lui, Orange, 1658 (puis Genève, 1659, Amsterdam, 1671).

- La pratique de l'oraison et meditation Chretienne, Genève, 1660.

- Le Iûne religieus ou le moyen de le bien faire, Genève, 1665.

- Jugement charitable et juste sur l'état present des Juifs, Amsterdam 1667.

- Le Triomphe de l'Eucharistie, ou la vraye doctrine du St. Sacrement, avec les moyens d'y bien participer, Amsterdam, 1667.

- Le Héraut du Grand Roy Jesus, ou Eclaircissement de la doctrine de Jean de Labadie, pasteur, sur le Règne glorieux de Jésus-Christ et de ses saints en la terre aux derniers temps, Amsterdam, 1667.

- L'Idée d'un bon pasteur et d'une bonne Eglise, Amsterdam, 1667.

- Les Divins Herauts de la Penitence au Monde..., Amsterdam, 1667.

- La Reformation de l'Eglise par le Pastorat, Middelbourg, 1667.

- Le Veritable Exorcisme, Amsterdam, 1667.

- Le Discernement d'une Veritable Eglise suivant l'Ecriture Sainte, Amsterdam, 1668.

- La Puissance eclesiastique bornée à l'Ecriture et par Elle..., Amsterdam, 1668.

- Manuel de Pieté, Middelbourg 1668.

- Declaration Chrestienne et sincère de plusieurs Membres de l'Eglise de Dieu et de Jésus-Christ touchant les Justes Raisons et les Motifs qui les obligent à n'avoir point de Communion avec le synode dit Vualon, La Haye, 1669.

- Points fondamentaux de la vie vraimant Chretiene, Amsterdam 1670.

- Abrégé du Veritable Christianisme et Téoretique et pratique..., Amsterdam, 1670.

- Le Chant Royal du Grand Roy Jésus, ou les Hymnes et Cantiques de l'Aigneau..., Amsterdam, 1670.

- Receüil de diverses Chansons Spiritüeles, Amsterdam, 1670.

- L'Empire du S. Esprit sur les Ames..., Amsterdam, 1671.

- Eclaircissement ou Declaration de la Foy et de la pureté des sentimens en la doctrine des Srs. Jean de Labadie, Pierre Yvon, Pierre Dulignon..., Amsterdam, 1671.

- Veritas sui vindex, seu solemnis fidei declaratio..., Herfordiae, 1672.

- Jesus revelé de nouveau..., Altona, 1673.

- Fragmens de quelques poesies et sentimens d'esprit..., Amsterdam, 1678.

- Poésies sacrées de l'amour divin, Amsterdam, 1680.

- Recueil de Cantiques spirituels, Amsterdam, 1680.

- Le Chretien regeneré ou nul, Amsterdam, 1685.

See also

References

- ↑ Revue d'ascétique et de mystique. 41: 339–385. 1965. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Saxby, Trevor J. (1987). "Chapter 6". Quest for the New Jerusalem, Jean de Labadie and the Labadists, 1610-1744. ISBN 90-247-3485-1.

- ↑ 'Openaccess' website article (pdf retrieved 5.11.08)

- ↑ Acts 2:44, 4:32

- ↑ Eukleria, seu melioris partis electio (‘On choosing the better part’), (1673)

- ↑ Una Birch, Anna van Schurman, Artist, Scholar, Saint (1909)

- ↑ van der Weiden RM, Hoogsteder WJ (October 1997). "A new light upon Hendrik van Deventer (1651-1724): identification and recovery of a portrait". J R Soc Med. 90 (10): 567–9. PMC 1296602

. PMID 9488017.

. PMID 9488017. - ↑ Glausser, Wayne (1998). Locke and Blake: a conversation across the eighteenth century. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 23–4. ISBN 0-8130-1570-7.

- ↑ Labadisten in Suriname, West-Indische Gids, 8 (1827), 193-218

- ↑ Maria Sybilla Merian, Artist, Naturalist, Magazine Antiques, (August 2000)

- ↑ Danckaerts J. Journal of Jasper Danckaerts, 1679-1680.

- 1 2 Nead (1980). The Pennsylvania-German in the Settlement of Maryland. Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 978-0-8063-0678-0.

- ↑ Green EJ (1988). "The Labadists of Colonial Maryland". Communal Societies. 8: 104–121.

- ↑ Penn W (1981). Dunn RS, Dunn MM, eds. The papers of William Penn. 1. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 216. ISBN 0-8122-7800-3.

Bibliography

The most important study on Labadie's life and works is:

- Trevor John Saxby, The quest for the new Jerusalem, Jean de Labadie and the Labadists, 1610-1744, Dordrecht-Boston-Lancaster, 1987.

- Michel de Certeau, La Fable mystique: XVIe-XVIIe siècle, Paris, 1987.

- Pierre Antoine Fabre, Nicolas Fornerod, Sophie Houdard et Maria Cristina Pitassi (sous la dir. de ), Lire Jean de Labadie (1610-1674). Fondation et affranchissement, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2016, ISBN 978-2-406-05886-1.

- Fabrizio Frigerio, L'historiographie de Jean de Labadie, État de la question, Genève, 1976.

- Fabrizio Frigerio, "La poesia di Jean de Labadie e la mistica quietista", in: Conoscenza religiosa, 1978, 1, p. 60-66.

- M. Goebel, Geschichte des christlichen Lebens in der rheinischwestphälischen evangelischen Kirche, II. Das siebzehnte Jahrhundert oder die herrschende Kirche und die Sekten, Coblenz, 1852.

- W. Goeters, Die Vorbereitung des Pietismus in der reformierten Kirche der Niederlande bis zur labadistischen Krisis 1670, Leipzig, 1911.

- Cornelis B. Hylkema, Reformateurs. Geschiedkündige studiën over de godsdienstige bewegingen uit de nadagen onzer gouden eeuw, Haarlem, 1900-1902.

- Leszek Kolakowsky, Chrétiens sans Église, La Conscience religieuse et le lien confessionnel au XVIIe siècle, Paris, 1969.

- Alain Joblin, "Jean de Labadie (1610-1674): un dissident au XVIIe siècle?", in: Mélanges de sciences religieuses, 2004, vol. 61, n.2, p. 33-44.

- Anne Lagny, (éd.), Les piétismes à l'âge classique. Crise, conversion, institutions, Villeneuve- d'Ascq, 2001.

- Johannes Lindeboom, Stiefkideren van het christendom, La Haye, 1929.

- Georges Poulet, Les métamorphoses du cercle, Paris, 1961.

- Jean Rousset, "Un brelan d'oubliés", in L'esprit créateur, 1961, t. 1, p. 61-100.

- Trevor John Saxby, The quest for the new Jerusalem, Jean de Labadie and the Labadists, 1610-1744, Dordrecht-Boston-Lancaster, 1987.

- M. Smits van Waasberghe, "Het ontslag van Jean de Labadie uit de Societeit van Jezus", in: Ons geesteljk erf, 1952, p. 23-49.

- Otto E. Strasser-Bertrand - Otto J. De Jong, Geschichte des Protestantismus in Frankreich und den Niederlanden, Göttingen, 1975.

- Daniel Vidal, Jean de Labadie (1610-1674) Passion mystique et esprit de Réforme, Grenoble, 2009.

- H. Van Berkum, De Labadie en de Labadisten, eene bladzijde uit de geschiedenis der Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk, Snek, 1851.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry

- Article from the 1914 Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge

- Encyclopedia.com on Labadie

- Encyclopedia.com on Labadists

- Britannica.com on Labadie

- Encarta on Labadie (Archived 2009-10-31)

- From The Awakening of America by V. F. Calverton

- Trahair, Richard C. S. (1999). Utopias and Utopians: an historical dictionary. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29465-8.

- Kross, Andrea; Morris, James A. (2004). Historical dictionary of utopianism. Metuchen, N.J: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4912-7.