Senegalese wrestling

Senegalese wrestling (Njom in Serer, Lutte sénégalaise in French, Laamb in Wolof, Siɲɛta in Bambara) is a type of folk wrestling traditionally performed by the Serer people and now a national sport in Senegal and parts of The Gambia, and is part of a larger West African form of traditional wrestling (fr. Lutte Traditionnelle).[1] The Senegalese form traditionally allows blows with the hands (frappe), the only one of the West African traditions to do so. As a larger confederation and championship around Lutte Traditionnelle has developed since the 1990s, Senegalese fighters now practice both forms, called officially Lutte Traditionnelle sans frappe (for the international version) and Lutte Traditionnelle avec frappe for the striking version.[2]

History

It takes its root from the wrestling tradition of the Serer people - formally a preparatory exercise for war among the warrior classes depending on the technique.[3][4] In Serer tradition, wrestling is divided into different techniques with mbapate being one of them. It was also an initiation rite among the Serers, the word Njom derives from the Serer principle of Jom (from Serer religion), meaning heart or honour in the Serer language.[5][6] The Jom principle covers a huge range of values and beliefs including economic, ecological, personal and social values. Wrestling stems from the branch of personal values of the Jom principle.[5] One of the oldest known and recorded wrestler in Senegambia was Boukar Djilak Faye (a Serer) who lived in the 14th century in the Kingdom of Sine. He was the ancestor of the Faye Paternal Dynasty of Sine and Saloum (both Kingdoms in present-day Senegal).[7] The njom wrestling spectacle was usually accompanied by the kim njom - the chants made by young Serer women in order to reveal their gift of "poetry" (ciid in Serer[8] ). The Wolof word for wrestling - Laamb, derives from the Serer language Fara-Lamb Siin (Fara of Mandinka origin whilst Lamb of Serer origin) the chief griot who used to beat the tam-tam of Sine called Lamb or Laamb in Serer.[9] The lamb was part of the music accompaniment of wrestling in pre-colonial times as well as after Senegal's independence. It was also part of the Njuup tradition (a conservative Serer music repertoire, the progenitor of Mbalax[10][11][12]).

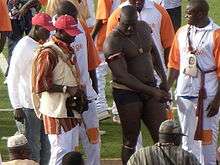

Transcending ethnic groups, the sport enjoys the status of national sport.[13] Traditionally, young men also used to fight as a distraction, to court wives, prove their manliness, and bring honor to their villages. Usually each wrestler (called mbër) performed a particular dance (called a bàkk) before the start of the combat.

Today it is very popular in the country as an indication of male athletic strength and ability.[14] Presently, wrestling is arranged by business-promoters who offer prizes for the winners.

Goal

One of the main objectives is to throw the opponent to the ground by lifting him up and over, usually outside a given area.

Training

Senegalese wrestlers train extremely hard and may perform press ups and various difficult physical exercises throughout the day to build up their strength. However while they believe strength is important they also believe that there is an element of luck in the winner, and may perform rituals before a match to increase their chances. Common to Senegalese wrestlers is rubbing a foot on a stone or rubbing themselves with lotions or oils to increase "good luck".

Media

In April 2008 a BBC documentary entitled Last Man Standing covered the lives of a group of British and American hopefuls at a boot camp in Senegal who took on Senegalese opponents.[15] Laamb was featured in the 2005 film L'Appel des arènes (English title Wrestling Grounds).

Etymology

Laamb is the Wolof word for wrestling which is borrowed from Serer Fara-Lamb Siin.[16] The Serer word for wrestling is njom which derives from the Serer word jom (heart or honour).[17][18]

Champions

Since the 1950s, Senegalese Wrestling, like its counterparts in other areas of West Africa, has become a major spectator sport and cultural event. The champions of traditional wrestling events are celebrities in Senegal, with fighters such as Yékini (Yakhya Diop), Tyson (Mohamed Ndao), and Bombardier (Serigne Ousmane Dia) the best known.[19]

References

- ↑ For example, see the Nigerian variant: Jolijn Geels. Niger. Bradt London and Globe Pequot New York (2006). ISBN 1-84162-152-8 pp.77-8.

- ↑ Government of Senegal: COMITE NATIONAL DE GESTION DE LA LUTTE.

- ↑ Senghor, Léopold Sédar, Brunel, Pierre, Poésie complète, CNRS éditions, 2007, p 425, ISBN 2-271-06604-2

- ↑ Tang, Patricia, Masters of the sabar: Wolof griot percussionists of Senegal, p144. Temple University Press, 2007. ISBN 1-59213-420-3

- 1 2 (French) Gravrand, Henry : "L’HERITAGE SPIRITUEL SEREER : VALEUR TRADITIONNELLE D’HIER, D’AUJOURD’HUI ET DE DEMAIN" [in] Ethiopiques, numéro 31, révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine, 3e trimestre 1982

- ↑ Gravrand, Henry, La Civilisation Sereer, Pangool. Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines. 1990, p 40

- ↑ Diouf, Niokhobaye. "Chronique du royaume du Sine." Suivie de notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin. (1972). Bulletin de l'Ifan, Tome 34, Série B, n° 4, p 4(p 706), (1972)

- ↑ Ciid means poetry in Serer, it can also mean the reincarnated or the dead who seek to reincarnate in Serer religion. Two chapters are devoted to this by Faye see:

- Faye, Louis Diène, Mort et Naissance Le Monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines (1983), p 34, ISBN 2-7236-0868-9

- ↑ Faye, Louis Diène, Mort et Naissance Le Monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines (1983), p 34, ISBN 2-7236-0868-9.

- Not to be confused with the Paar - the chief Serer griot who used to beat the tam-tam (there are different kinds of tam-tams in Serer; each one has their purpose and the special occasions they should be used) when an important person dies (see page 22).

- ↑ "Nelson Mandela: Latter day saint - Prospect Magazine". Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ "Youssou N'Dour: An Unlikely Politician". Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ (French) Agence de Presse Sénégalaise (APS) "Rémi Diégane Dioh présente samedi son CD dédié à Senghor"

- ↑ "The Official Home Page of the Republic of Sénégal". Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ "Rambax catches the rhythm of wrestling". MIT News. 13 April 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ↑ www.bbc.co.uk

- ↑ Faye, Louis Diène, Mort et Naissance Le Monde Sereer, Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines (1983), p 34, ISBN 2-7236-0868-9.

- ↑ Gravrand, Henry : "L’HERITAGE SPIRITUEL SEREER : VALEUR TRADITIONNELLE D’HIER, D’AUJOURD’HUI ET DE DEMAIN" [in] Ethiopiques, numéro 31, révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine, 3e trimestre 1982

- ↑ Glbal timoto (video) and snippits)

- ↑ For example, see this article on the private life of Yekini, LUTTE TRADITIONNELLE - 15e ANNIVERSAIRE DE YEKINI : Mbagnick, digne fils de Mohamed Ndiaye Robert Diouf, Le Soleil , 3 March 2008.

Bibliography

- Senghor, Léopold Sédar, Brunel, Pierre, "Poésie complète," CNRS éditions, 2007, ISBN 2-271-06604-2

- Tang, Patricia, Masters of the sabar: Wolof griot percussionists of Senegal, p144. Temple University Press, 2007. ISBN 1-59213-420-3

- Gravrand, Henry : "L’HERITAGE SPIRITUEL SEREER : VALEUR TRADITIONNELLE D’HIER, D’AUJOURD’HUI ET DE DEMAIN" [in] Ethiopiques, numéro 31, révue socialiste de culture négro-africaine, 3e trimestre 1982

- Gravrand, Henry, "La Civilisation Sereer, Pangool.'"' Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines. 1990.

- Diouf, Niokhobaye. "Chronique du royaume du Sine." Suivie de notes sur les traditions orales et les sources écrites concernant le royaume du Sine par Charles Becker et Victor Martin. (1972). Bulletin de l'Ifan, Tome 34, Série B, n° 4, (1972)

- Faye, Louis Diène, "Mort et Naissance Le Monde Sereer," Les Nouvelles Edition Africaines (1983), ISBN 2-7236-0868-9

- Geels, Jolijn. Niger. Bradt London and Globe Pequot New York (2006). ISBN 1-84162-152-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lutte sénégalaise. |

- www.arenebi.com Senegalese wrestling news

- Sénégal LUTTE : 2007, année d’innovations, surprises et sacre. La Sentinelle (Dakar), 27 December 2007