La Reyne le veult

"La Reyne le veult" ("The Queen wills it") or "Le Roy le veult" ("The King wills it") is a Norman French phrase used in the Parliament of the United Kingdom to signify that a public bill (including a private member's bill) has received royal assent from the monarch of the United Kingdom. It is a legacy of the time prior to 1488 when Parliamentary and judicial business was conducted in French, the language of the educated classes after the Norman Conquest of 1066. It is one of a small number of Norman French phrases that continue to be used in the course of Parliamentary procedure.

Usage

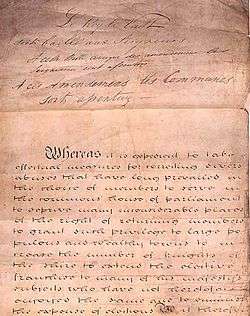

The phrase is used to signify that the Monarch has granted his or her royal assent to a bill in order to make it become law. It is used by the Clerk of the Parliaments in the House of Lords. It is only used after the Lord Chancellor accompanied by the Lords Commissioners, has read out the Letters patent for the bill. The Clerk of the Crown then reads out the short title of the bill and the Clerk of the Parliament responds by saying the phrase towards the House of Commons at the bar of the House for each bill.[1][2] The phrase is also written on the paper of the bill to show that the Monarch granted royal assent to the bill.[3]

The phrase has been misused on other bills, just as the wrong phrase has also been used for government bills. There are a few occasions where this has happened, most notably on the Act of Supremacy 1558 where "Soit fait comme il est désiré" ("Let it be done as it is desired"), the phrase used for personal bills, was used instead of "La Reyne le veult".[4]

Should royal assent be refused, the expression "La Reyne/Le Roy s'avisera," "The Queen/King will be advised" (i.e., will take the bill under advisement), a paraphrase of the Law Latin euphemism Regina/Rex consideret ("The Queen/King will consider [the matter]"), would be used, though no British monarch has denied royal assent since Queen Anne withheld it from the Scottish Militia Bill in 1708.[5]

For a supply bill, an alternative phrase is used; La Reyne/Le Roy remercie ses bons sujets, accepte leur benevolence, et ainsi le veult ("The Queen/King thanks her/his good subjects, accepts their bounty, and wills it so").[6] For a private bill, the phrase Soit fait comme il est désiré ("Let it be done as it is desired") is used.

History

The practice of giving royal assent originated in the early days of Parliament to signify that the King intended for something to be made law.[7][8] Norman French came to be used as the standard language of the educated classes and of the law, though Latin continued to be used alongside it.[9] The work of the Parliament of England was conducted entirely in French until the latter part of Edward III's reign (1327–1377) and English was only rarely used before the reign of Henry VI (1422–61, 1470–71). Royal assent was occasionally given in English, though more usually in French.[10] The practice of recording Parliamentary statutes in French or Latin ceased by 1488 and statutes have been published in English ever since.[9]

During the period of the Protectorate, when the Lord Protector (Oliver Cromwell and later his son Richard Cromwell) governed the country, assent was given in English. The old practice of giving assent in Norman French was resumed following the English Restoration in 1660 and has continued ever since. There has only been one attempt to abolish it, when the House of Lords passed a bill in 1706 "for abolishing the use of the French tongue in all proceedings in Parliament and courts of justice." The bill failed to pass the House of Commons. Although the use of French in courts was abolished in 1731, Parliamentary practice was unaffected.[10]

References

- ↑ "Interview with the former Clerk of the Parliaments-part two". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 2007-11-03. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ↑ The Committee Office (2007-02-19). "Royal Assent By Commission". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ↑ "Documenting Democracy". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ↑ Elton, G.R. (1989). The Parliament of England: 1559-1581 (reprint ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0521389887.

- ↑ Erskine May, pp. 372–3

- ↑ Bennion, Francis (November 1981). "Modern Royal Assent Procedure at Westminster" (PDF). Statute Law Review. 3 (2): 133–147.

- ↑ "La Reyne le Veult The making and keeping of Acts at Westminster" (PDF). House of Lords. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ↑ David Richards (2011-12-08). "Race against time to record the language spoken by William the Conqueror before it dies out". Daily Mail. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- 1 2 Crabbe, V.C.R.A.C (2012). Understanding Statutes. London: Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 9781135352677.

- 1 2 Erskine May, Thomas (1844). Erskine May: Parliamentary Practice. London: Charles Knight & Co. p. 373. OCLC 645178915.