L'Assommoir

|

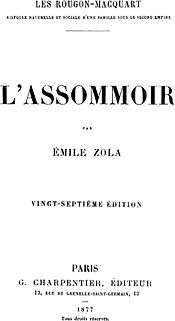

Cover of 1877 Charpentier edition of L'Assommoir | |

| Author | Émile Zola |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Series | Les Rougon-Macquart |

| Genre | Novel |

Publication date | 1877 |

| Media type | Print (Serial, Hardback & Paperback) |

| Preceded by | Son Excellence Eugène Rougon |

| Followed by | Une Page d'amour |

L'Assommoir [lasɔmwaʁ] (1877) is the seventh novel in Émile Zola's twenty-volume series Les Rougon-Macquart. Usually considered one of Zola's masterpieces, the novel—a study of alcoholism and poverty in the working-class districts of Paris—was a huge commercial success and helped establish Zola's fame and reputation throughout France and the world.

Plot summary

The novel is essentially the story of Gervaise Macquart, who was featured briefly in the first novel in the series, La Fortune des Rougon, running away to Paris with her shiftless lover Lantier to work as a washerwoman in a hot, busy laundry in one of the seedier areas of the city. L'Assommoir begins with Gervaise and her two young sons being abandoned by Lantier, who takes off for parts unknown; she later takes up with Coupeau, a teetotal roofing engineer, and they are married in one of the most famous set-pieces of Zola's fiction; the account of the wedding party's chaotic trip to the Louvre is perhaps the novelist's most famous passage. Through a combination of happy circumstances Gervaise is able to raise enough money to open her own laundry, and the couple's happiness appears to be complete with the birth of a daughter, Anna, nicknamed Nana (the protagonist of Zola's later novel of the same title).

The second half of the novel deals with the downward trajectory of Gervaise's life from this happy high point. Coupeau is injured in a fall from the roof of a new hospital he is working on, and during his lengthy and painful convalescence he takes to drink. Only a few chapters pass before Coupeau is a vindictive alcoholic, with no intention of trying to find more work; Gervaise struggles to keep her home together, but her excessive pride leads her to a number of embarrassing failures and before long everything is going downhill. The home is further disrupted by the return of Lantier, warmly welcomed by Coupeau—by this point losing interest in both Gervaise and life itself, and becoming seriously ill—and the ensuing chaos and financial strain is too much for Gervaise, who loses her laundry-shop and is sucked into debt. She decides to join Coupeau in the drinking and soon slides into heavy alcoholism too, prompting Nana—already suffering from the chaotic life at home and getting into trouble on a daily basis—to run away from her parents' home and become a streetwalker. The novel continues in this unhappy vein until Gervaise dies.

Themes and criticism

Zola spent an immense amount of time researching Parisian street argot for his most realistic novel to that date, using a large number of obscure contemporary slang words and curses to capture an authentic atmosphere. His shocking descriptions of conditions in working-class 19th-century Paris drew widespread admiration for his realism, as it still does. L'Assommoir was taken up by temperance workers across the world as a tract against the dangers of alcoholism, though Zola always insisted there was considerably more to his novel than that. The novelist also drew criticism from some quarters for the depth of his reporting, either for being too coarse and vulgar or for portraying working-class people as shiftless drunkards. Zola rejected both these criticisms out of hand; his response was simply that he had presented a true picture of real life.

The title

The title L'Assommoir cannot be properly translated into English. It is adapted from the French verb "assommer" meaning to stun or knock out. The noun is a colloquial term popular in late nineteenth-century Paris, referring to a shop selling cheap liquor distilled on the premises "where the working classes could drown their sorrows cheaply and drink themselves senseless".[1] Perhaps the closest equivalent terms in English are the slang adjectives "hammered" and "plastered". In the absence of a corresponding noun, English translators have rendered it as The Dram Shop, The Gin Palace, The Drunkard, and The Drinking Den. Most translators choose to retain the original French title.

Translations

L'Assommoir has often been translated, and there are several unexpurgated editions widely available. Among them is The Drinking Den, translated by Robin Buss.[2]

Adaptations

The American film The Struggle (1931), directed by D. W. Griffith, is a loose adaptation of the novel.

The French film Gervaise (1956), directed by René Clément, is an adaptation of the novel.

References

External links

- L'Assommoir, available at Internet Archive (English, illustrated scanned books)

- L'Assommoir at Project Gutenberg (English, HTML and plain text)

- L'assommoir at Project Gutenberg (French, HTML and plain text)

- (French) L'Assommoir, audio version

- L'Assommoir in French with English translation

-

L'Assommoir public domain audiobook at LibriVox

L'Assommoir public domain audiobook at LibriVox