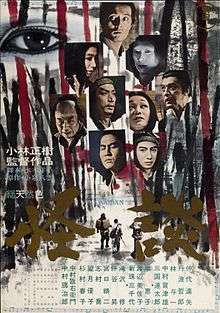

Kwaidan (film)

| Kwaidan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Masaki Kobayashi |

| Produced by | Shigeru Wakatsuki[1] |

| Screenplay by | Yoko Mizuki[1] |

| Based on |

Stories and Studies of Strange Things by Lafcadio Hearn |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Toru Takemitsu[1] |

| Cinematography | Yoshio Miyajima[1] |

| Edited by | Hisashi Sagara[1] |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 182 minutes[1] |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Kwaidan (怪談 Kaidan, literally "strange stories") is a 1965 Japanese anthology horror film directed by Masaki Kobayashi. It is based on stories from Lafcadio Hearn's collections of Japanese folk tales, mainly Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, for which it is named. The film consists of four separate and unrelated stories. Kwaidan is an archaic transliteration of Kaidan, meaning 'ghost story'. It won the Special Jury Prize at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival,[2] and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film.[3]

Plot

The Black Hair

"The Black Hair" (黒髪 Kurokami) was adapted from "The Reconciliation", which appeared in Hearn's collection Shadowings (1900). An impoverished swordsman living in Kyoto divorces his wife, a weaver, for a woman of a wealthy family to attain greater social status. He takes his new wife to his new position as a district governor. However, the swordsman's second marriage proves to be unhappy. With his second wife being callous and shallow, the swordsman regrets leaving his more devoted and patient ex-wife.

One night while he sleeps, the second wife discovers that the swordsman not only married her to obtain her family's wealth, but also still longs for his old life in Kyoto with his ex-wife, and is furious. After lashing out at him for his ungrateful behavior, the second wife returns to her marriage chambers in humiliation. When he is told to go into the chambers to reconcile with her by a lady-in-waiting, the swordsman refuses, stating his intent to return home and reconcile with his true wife. He tells her that it is his foolish youth in being impoverished that made him marry his second wife. Admitting that he didn't love her, the swordsman tells the lady-in-waiting to inform her that their marriage is over and she can return to her family.

After a few years, the swordsman returns to Kyoto and finds the house in a mess. He reconciles with his ex-wife, who refuses to let him punish himself. The wife understands he only divorced her so he can better support her, and the she is happy to see him again "only for a moment" to which the man replies that he will never leave her again. Before going to bed, the swordsman promises her that they won't have to worry about poverty anymore because of his new resources and connections and he will never leave her side again. The two happily exchange wonderful stories about the past and the future until the swordsman fell asleep. He wakes up the following day, finding that he had been sleeping next to the rotted corpse of his wife. Rapidly aging and attacked by black hair, he leaves the house, only to be further attacked by black hair.

The Woman of the Snow

"The Woman of the Snow" (雪女 Yukionna) is an adaptation from Hearn's Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things (1903). In the Musashi Province, a woodcutter named Minokichi takes refuge in a fisherman's hut during a snowstorm alongside his mentor Mosaku. Minokichi finds Mosaku killed by a Yuki-onna, who spares Minokichi because of his youth. Yuki-onna warns him to never mention what happened or she will kill him. Keeping his word, Minokichi later meets a young woman named Yuki who resembles the ghost he encountered. She reveals that she is on her way to Edo for she lost her family and her relatives had got her a position as a lady-in-waiting. Minokichi takes Yuki to his home to rest up. His mother takes a liking to Yuki and asks her to stay. Yuki never leaves for Edo and Minokichi falls in love with her. The two marry and have children, living happily for ten years. The female villagers are in awe of Yuki's youth for after having three children, she still looks the same. They noted that Minokichi's mother talked highly of Yuki, which is unusual because in their village, most mothers talk ill of their daughters-in-law no matter how good a wife she may be. One night, during a snowstorm, Minokichi tells her that her appearance reminds him of the Yuki-onna he met, telling her of the strange event. It is then that Yuki reveals herself to be the Yuki-onna. She tells him that he broke his word, yet refrains from killing him because of their children. Yuki then leaves Minokichi with the children, warning to treat them well or she will return and kill him. She disappears into the snowstorm, leaving Minokichi heartbroken.

Hoichi the Earless

"Hoichi the Earless" (耳無し芳一の話 Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi) is also adapted from Hearn's Kwaidan (though it incorporates aspects of The Tale of the Heike that are mentioned, but never translated, in Hearn's book). It depicts the folkloric tale of Hoichi the Earless, a blind musician, or biwa hoshi, whose specialty is singing The Tale of the Heike, about the Battle of Dan-no-ura, fought between the Taira and Minamoto clans during the last phase of the Genpei War. He is subsequently called in to sing for a royal family. His friends and priests grows concerned that he may be singing for ghosts as soon as he answered the call. To protect Hoichi, a priest and his acolyte write the text of The Heart Sutra on his body, and instruct him to go outside and sit still as if in meditation. They forget to write on his ears, which are subsequently visible to the ghost which comes to fetch him. The ghost seeks to bring back as much of Hoichi as possible, and rips his ears off.

In a Cup of Tea

"In a Cup of Tea" (茶碗の中 Chawan no Naka) is adapted from Hearn's Kottō: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs (1902). A writer who is anticipating a visit from the publisher writes a story about a samurai who keeps seeing the face of a strange man in a cup of tea.

Cast

Kurokami

|

Yuki-Onna

|

Hoichi the Earless

|

Chawan no naka

|

Release

The roadshow version of Kwaidan was released theatrically in Japan on January 6, 1965 where it was distributed by Toho.[1] The Japanese general release for Kwaidan began on February 27, 1965.[4] Kwaidan was reedited to 125 minutes in the United States for its theatrical release which eliminated "The Woman of the Snow" segment" after the film's Los Angeles premiere.[1] It was released in the United States on July 15, 1965 where it was distributed by Continental Distributing.[1] Kwaidan was re-released theatrically in Japan on November 29, 1982 in Japan as part of Toho's 50th anniversary.[5]

Reception

In Japan the film won Yoko Mizuki the Kinema Jumpo award for Best Screenplay. It also won awards for Best Cinematography and Best Art Direction at the Mainichi Film Concours.[1] The film won international awards including Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards.[6] Film review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported an approval rating of 85%, based on 20 reviews, with a rating average of 7.2/10.[7] In contemporary reviews, the Monthly Film Bulletin commented on the colour in the film, stating that "it is not so much that the colour in Kwaidan is ravishing...as the way Kobayashi uses it to give these stories something of the quality of a legend."[8] The review concluded that the Kwaidan was a film "whose details stay on in the mind long after one has seen it."[8] Bosley Crowther (New York Times) stated that director Kobayashi "merits excited acclaim for his distinctly oriental cinematic artistry. So do the many designers and cameramen who worked with him. "Kwaidan" is a symphony of color and sound that is truly past compare."[9] Variety described the film as "done in measured cadence and intense feeling" and tht it was "a visually impressive tour-de-force."[10]

In his Harakiri review, Roger Ebert described Kwaidan as "an assembly of ghost stories that is among the most beautiful films I've seen".[11]

See also

- List of ghost films

- List of submissions to the 38th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Japanese submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Galbraith IV 2008, p. 217.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Kwaidan". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ "The 38th Academy Awards (1966) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ↑ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 218.

- ↑ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 332.

- ↑ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 215.

- ↑ "Kaidan (Kwaidan) (Ghost Stories) (1964) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- 1 2 D.W. (1967). "Kwaidan". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 34 no. 396. London: British Film Institute. pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (November 23, 1965). "Screen: 'Kwaidan,' a Trio of Subtle Horror Tales:Fine Arts Theater Has Japanese Thriller". New York Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ↑ Galbraith IV 1994, p. 100.

- ↑ "Harakiri Movie Review". November 16, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

Sources

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1994). Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films. McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-853-7.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 1461673747.

External links

- Kwaidan at the Internet Movie Database

- Kwaidan at Rotten Tomatoes

- Kwaidan at AllMovie

- "怪談 (Kaidan)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- Text of Lafcadio Hearn stories that were adapted for Kwaidan

- The Reconciliation at K.Inadomi's Private Library

- The Story of Mimi-nashi-Hōichi at K.Inadomi's Private Library

- Yuki-Onna at K.Inadomi's Private Library