Republic of Mahabad

| Republic of Mahabad | ||||||||||

| کۆماری مەهاباد Komara Mehabadê | ||||||||||

| De-facto autonomous, Soviet-allied state | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Anthem Ey Reqîb Oh Enemy | ||||||||||

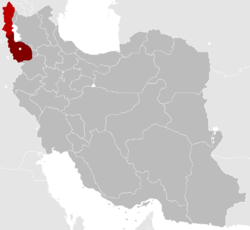

Approximate extent of the Republic of Mahabad. Iran is shown in dark grey. | ||||||||||

| Capital | Mahabad | |||||||||

| Languages | Kurdish Kurmanji Sorani Gorani Zazaki | |||||||||

| Government | Communist state | |||||||||

| President | Qazi Muhammad (KDPI) | |||||||||

| Prime Minister | Haji Baba Sheikh (KDPI) | |||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | |||||||||

| • | Autonomy declared | January 22, 1946 | ||||||||

| • | Soviet withdrawal | June 1946 | ||||||||

| • | Iran establishes control | December 15, 1946 | ||||||||

| • | Leaders executed | March 30, | ||||||||

| Currency | Soviet ruble | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Republic of Mahabad (Kurdish: کۆماری مەھاباد Komara Mehabadê; Persian: جمهوری مهاباد) was a short-lived self-governing state in present-day Iran.[1][2][3] The Republic of Mahabad arose alongside the Azerbaijan People's Government, a similarly short-lived state.

The capital of Republic of Mahabad was the city of Mahabad, in northwestern Iran. The state encompassed a small territory, including Mahabad and the adjacent cities of Piranshahr and Ushnaviya.[4] The republic's foundation and demise was a part of the Iran crisis during the opening stages of the Cold War.

Background

Iran was invaded by the Allies in late August 1941, with the Soviets controlling the north. In the absence of a central government, the Soviets attempted to attach northwestern Iran to the Soviet Union, and promoted Kurdish nationalism. From these factors resulted a Kurdish manifesto that above all sought autonomy and self-government for the Kurdish people in Iran within the limits of the Iranian state.[5]

In the town of Mahabad, inhabited mostly by Kurds, a committee of middle-class people supported by tribal chiefs took over the local administration. A political party called the Society for the Revival of Kurdistan (Komeley Jiyanewey Kurdistan or JK) was formed. Qazi Muhammad, head of a family of religious jurists, was elected as chairman of the party. Although the republic was not declared until December 1945, Qazi's committee administered the area for more than five years until the fall of the republic.[6]

Foundation

In September 1945, Qazi Muhammad and other Kurdish leaders visited Tabriz to seek the backing of a Soviet consul to found a new republic, and were then redirected to Baku, Azerbaijan SSR. There, they learned that the Democratic Party of Azerbaijan was planning to take control of Iranian Azerbaijan. On December 10, the Democratic Party took control of East Azerbaijan Province from Iranian government forces, forming the Azerbaijan People's Government. Qazi Muhammad decided to do likewise, and on December 15, the Kurdish People's Government was founded in Mahabad. On January 22, 1946, Qazi Muhammad announced the formation of the Republic of Mahabad. Some of the aims mentioned in the manifesto include:[4]

- Autonomy for the Iranian Kurds within the Iranian state.

- The use of Kurdish as the medium of education and administration.

- The election of a provincial council for Kurdistan to supervise state and social matters.

- All state officials to be of local origin.

- Unity and fraternity with the Azerbaijani people.

- The establishment of a single law for both peasants and notables.

Relationship to the Soviets

The Republic of Mahabad depended on Soviet support. Archibald Bulloch Roosevelt, Jr., grandson of the former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, wrote in "The Kurdish Republic of Mahabad" that a main problem of the People's Republic of Mahabad was that the Kurds needed the assistance of the USSR; only with the Red Army did they have a chance. However, its close relationship to the USSR alienated the republic from most Western powers, causing them to side with Iran. Qazi Muhammad did not deny that his republic was funded and supplied by the Soviets, but did deny that the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) was a communist party. He claimed that this was a lie fabricated by the Iranian military authorities, and added that his ideals were very different from the Soviets'.[7] Following the fall of Mahabad, the Soviets allowed for the safe passage of Mustafa Barzani and his followers into the Soviet Union.

Both contemporary friends and foes tended to exaggerate the Soviet role in the Republic of Mahabad. While Kurdish nationalist leaders Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou and Jalal Talabani stressed Soviet friendship and support, others like Robert Rossow Jr., the American Charges d'Affaires in neighboring Azerbaijan, and historian William Linn Westermann branded the republic a Soviet puppet state.[8] This notion was also widespread amongst Kurdish tribal leaders, many of whom disagreed with Qazi's leadership.[9]

The Soviets were however generally ambivalent towards the Kurdish administration. They did not maintain a garrison near Mahabad and also did not have any civil agent of sufficient standing to exercise any great influence. They encouraged Qazi's administration by practical benevolent operations such as providing motor transport, keeping out the Iranian army, and buying the whole of the tobacco crop. On the other hand, the Soviets initially did not like the Kurdish administration's refusal to be absorbed into the larger Democratic Republic of (Persian) Azerbaijan, and discouraged the formation of an independent Kurdish state.[6] Following the fall of Mahabad, they however allowed for the safe passage of Mustafa Barzani and his followers into the Soviet Union.

End

On March 26, 1946, due to pressure from Western powers including the United States, the Soviets promised the Iranian government that they would pull out of northwestern Iran. In June, Iran reasserted its control over Iranian Azerbaijan. This move isolated the Republic of Mahabad, eventually leading to its destruction.

Qazi Muhammad's internal support eventually declined, especially among the Kurdish tribes who had supported him initially. Their crops and supplies were dwindling, and their way of life was becoming hard as a result of the isolation. Economic aid and military assistance from the Soviet Union was gone, and the tribes saw no reason to support him. The townspeople and the tribes had a large divide between them, and their alliance for Mahabad was crumbling. The tribes and their leaders had only supported Qazi Muhammad for his economic and military aid from the Soviet Union. Once that was gone, many did not see any reason to support him. Other tribes resented the Barzanis, since they did not like sharing their already dwindling resources with them. Some Kurds deserted Mahabad, including one of Mahabad's own marshals, Amir Khan. Mahabad was economically bankrupt, and it would have been nearly impossible for Mahabad to have been economically sound without harmony with Iran.[4]

Those who stayed began to resent the Barzani Kurds, as they had to share their resources with them.

On December 5, 1946, the war council told Qazi Muhammad that they would fight and resist the Iranian army if they tried to enter the region. The lack of Kurdish tribal support however made Qazi Muhammad only see a massacre upon the Kurdish civilians performed by the Iranian army rather than Kurdish rebellion. This forced him to avoid war at all cost, even if it meant sacrificing himself for his people, which eventually happened and led to his execution.

On December 15, 1946, Iranian forces entered and secured Mahabad. Once there, they closed down the Kurdish printing press, banned the teaching of Kurdish language, and burned all Kurdish books that they could find. Finally, on March 31, 1947, Qazi Muhammad was hanged in Mahabad on counts of treason.[11] At the behest of Archie Roosevelt, Jr., who argued that Qazi had been forced to work with the Soviets out of expediency, U.S. ambassador to Iran George V. Allen urged the Shah not to execute Qazi or his brother, only to be reassured: "Are you afraid I'm going to have them shot? If so, you can rest your mind. I am not." Roosevelt later recounted that the order to have the Qazis killed was likely issued "as soon as our ambassador had closed the door behind him," adding with regard to the Shah: "I never was one of his admirers."[12]

Aftermath

Mustafa Barzani, with his soldiers from Iraqi Kurdistan, had formed the backbone of the Republic's forces. After the fall of the republic, most of the soldiers and four officers from the Iraqi army decided to return to Iraq. The officers were condemned to death upon returning to Iraq and are today honored along with Qazi as heroes martyred for Kurdistan. Several hundred of the soldiers chose to stay with Barzani. They defeated all efforts of the Iranian army to intercept them in a five-week march and made their way to Soviet Azerbaijan.[6]

In October 1958, Mustafa Barzani returned to Northern Iraq, beginning a series of struggles to fight for an autonomous Kurdish region under the KDP, carrying the same Kurdish flag that was used in Mahabad.

Massoud Barzani, the President of Iraqi Kurdistan as of 2015, is the son of Mustafa Barzani. He was born in Mahabad when his father was chief of the military of the Mahabad forces in Iranian Kurdistan.

See also

- Azerbaijan People's Government

- Persian Socialist Soviet Republic

- Autonomous Government of Khorasan

- Iran–Russia relations

Notes

- ↑ Romano, David (2006). The Kurdish Nationalist Movement: Opportunity, Mobilization and Identity. Cambridge Middle East studies, 22. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 9780521850414. OCLC 61425259.

- ↑ Chelkowski, Peter J.; Pranger, Robert J. (1988). Ideology and Power in the Middle East: Studies in Honor of George Lenczowski. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 399. ISBN 9780822307815. OCLC 16923212.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 9780691053424. OCLC 7975938.

- 1 2 3 McDowall 2004, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Allain, Jean (2004). International Law in the Middle East: Closer to Power than Justice. Ashgate Publishing Ltd. pp. 27–28.

- 1 2 3 C. J. Edmonds, Kurdish Nationalism, Journal of Contemporary History, pp.87-107, 1971, p.96

- ↑ Meiselas, Susan (1997). Kurdistan In the Shadow of History. Random House. p. 182. ISBN 0-679-42389-3.

- ↑ Voller 2014, p. 46.

- ↑ McDowall 2004, pp. 242.

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/uploads/files/azerbaijan_5_fig3.jpg

- ↑ McDowall 2004, pp. 243–246.

- ↑ Wilford, Hugh (2013). America's Great Game: The CIA's Secret Arabists and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Basic Books. p. 53. ISBN 9780465019656.

References

- "The Republic of Kurdistan: Fifty Years Later", International Journal of Kurdish Studies, 11, no. 1 & 2, (1997).

- The Kurdish Republic of 1946, William Eagleton, Jr. (London: Oxford University Press, 1963)

- (German) Moradi Golmorad: Ein Jahr autonome Regierung in Kurdistan, die Mahabad-Republik 1946 - 1947 in: Geschichte der kurdischen Aufstandsbewegungen von der arabisch-islamischen Invasion bis zur Mahabad-Republik, Bremen 1992, ISBN 3-929089-00-9

- (French) M. Khoubrouy-Pak: Une république éphémère au Kurdistan, Paris u.a. 2002, ISBN 2-7475-2803-0

- Archie Roosevelt, Jr., "The Kurdish Republic of Mahabad", Middle East Journal, no. 1 (July 1947), pp. 247–69.

- William Linn Westermann, "Kurdish Independence and Russian Expansion", Foreign Affairs, Vol. 24, 1945–1946, pp. 675–686

- Kurdish Republic of Mahabad, Encyclopedia of the Orient.

- The Kurds: People without a country, Encyclopædia Britannica

- McDowall, David A. (2004). Modern History of the Kurds (3rd ed.). I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-416-0.

- Meiselas, Susan Kurdistan In the Shadow of History, Random House, 1997. ISBN 0-679-42389-3

- Voller, Yaniv (2014). The Kurdish Liberation Movement in Iraq: From Insurgency to Statehood. Routledge. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-0415-70724-4.

- Yassin, Burhaneddin A., "A History of the Republic of Kurdistan", The International Journal of Kurdish Studies, 11, nos. 1-2 (1997): 115-240.

- Yassin, Burhaneddin A., Vision or Reality: The Kurds in the Policy of the Great Powers, 1941-1947, Lund University Press, Lund/Sweden, 1995. ISSN 0519-9700, ISBN 91-7966-315-X Lund University Press. ou ISBN 0-86238-389-7 Chartwell-Bratt Ltd.

- (Russian) Масуд Барзани. Мустафа Барзани и курдское освободительное движение. Пер. А. Ш. Хаурами, СПб, Наука, 2005.

- (Russian) М. С. Лазарев. Курдистан и курдский вопрос (1923—1945). М., Издательская фирма «Восточная литература» РАН, 2005.

- (Russian) Жигалина О. И. Национальное движение курдов в Иране (1918—1947). М., «Наука», 1988.

- (Russian) История Курдистана. Под ред. М. С. Лазарева, Ш. Х. Мгои. М., 1999.

- (Russian) Муртаза Зарбахт. От Иракского Курдистана до другого берега реки Аракс. Пер. с курдск. А. Ш. Хаурами. М.-СПб, 2003.

External links

- The Republic of Kurdistan in Mehabad, Encyclopaedia KURDISTANICA.

- Kurds at the crossroad

- Stearns, Peter N (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6 ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/ Bartleby.com.

Proclamation of the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad

- (Japanese) 消滅した国々-クルディスタン人民共和国

.png)