Kuči

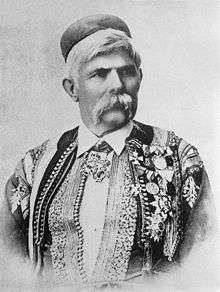

Kuči (Serbian Cyrillic: Кучи; pronounced [kût͡ʃi])[a] is a historical tribe and region in eastern Montenegro, north-east of Podgorica, extending along the border with Albania. The majority of inhabitants are Orthodox Christian while a Muslim and Roman Catholic minority exists. Marko Miljanov (1833–1901) led the tribe against the Ottoman Empire in the wars of 1861–62 and 1876–78; he had unified Kuči with Montenegro in 1874.

Geography

The unofficial centre is the Ubli village, which has about 1,500 residents and houses several institutions like a culture hall, the "Đoko Prelević" elementary school, a hospital, police station, and a former fabric factory. Ubli is situated in central Kuči with the center and villages of Prelevići, Pavićevići, Živkovići, Kostrovići, etc. Other villages are: Medun, Orahovo, Fundina, Koći, Kržanja, Kosor, Vrbica, Stravče, Zagreda, Raći in northern Kuči and Doljani, Murtovina, Stara Zlatica, Zlatica in southern Kuči.

The Kuči region itself can be divided into three major historical sub-regions:

- Old Kuči, Orthodox sub-tribe, which celebrates the slava of Mitrovdan (Saint Demetrius).

- Drekalovići, Orthodox sub-tribe, which celebrates the slava of Nikoljdan (Saint Nicholas).

- Zatrijebač (Triesh in Albanian), also known as Kučka krajina ("Kuči frontier"), mixed Albanian (Catholic and Muslim) and Orthodox sub-region, which celebrates the Nativity of the Theotokos. Includes the settlements of Benkaj, Budza, Cijevna, Delaj, Korita, Mužeška, Nikmaraš, Rudine, Poprat and Stjepovo.

History

Middle Ages

The legendary progenitor of the Kuči, Nenad, and his sons, were mentioned in the 1416–17 register of the Sanjak of Scutari.[1] Nenad descended from an Orthodox Serb noble family.[1] According to folklore, this family was the Mrnjavčević family; Nenad was the son of Gojko Mrnjavčević (fl. 1355).[2]

In the mid-15th century Kuči is mentioned as a Serbian Orthodox tribe.[3] When the Ottoman Empire occupied the Kuči area, the 1484 Ottoman defter (tax registry) registered 208 households in 11 villages. In the next one, 1497, it had had 338 households in 9 katuni (Pavlovići, Petrovići, Lješovići, Bitidosi, Lopari, Bankeći, Banjovići, Lazorce and Koći) and 2 villages.[4]

16th century

The Old Kuči constantly were in conflict with the Old Gruda; the Kuči were stronger, thus they stole livestock from Gruda, and even if only one Kuči would be killed in conflicts, and several Gruda, they would still penalize the whole tribe.[5]

In a 1582/83 defter (Ottoman tax registry), the Kuči nahiya had 13 villages, belonging to the Sanjak of Scutari.[6] In the villages of the nahiya, names were majority Serbian, although Albanian were very common as well.[6]

17th century

In 1610, the Kuči (Cucci) are mentioned by Marino Bizzi as being half Orthodox and half Catholic.[7] In Venetian public servant Mariano Bolizza's report (1614) Chuzzi Albanesi ("Albanian Kuči") was a village of 490 houses of predominantly Roman Catholic religion, led by Lale Drekalov and Niko Rajckov, with 1,500 men-in-arms, "a very warlike and brave people".[8] Bolizza's use of Albanian and calling them Catholics is deemed unacceptable, since it is known that Orthodoxy was the predominant religion of the tribe since their first mention, the Orthodox being the tribe's founders, and also the fact that Bizzi did not group them into the Albanians (the five tribes of Klimenti, Hoti, Gruda, Kastrati and Shkreli).[7] The Kuči, Bratonožići and part of Plava were under the soldiers of Medun, the spahee, but the commander was not named; and the highlanders would pay the Ottoman officials a portion of their income.[9] Under the leadership of Lale Drekalov (fl. 1608–14), the Catholics of Kuči converted to Orthodoxy.[10] In the second half of 1614, the Bjelopavlići, Kuči, Piperi, and Kelmend sent a letter to the kings of Spain and France claiming they were independent from Ottoman rule and did not pay tribute to the empire.[11] Between 1614 and 1621 the Kuči were mentioned as Ottoman subjects.[12] In 1658, the seven tribes of Kuči, Vasojevići, Bratonožići, Piperi, Klimenti, Hoti and Gruda allied themselves with the Republic of Venice, establishing the so-called "Seven-fold barjak" or "alaj-barjak", against the Ottomans.[10]

In 1688, the Kuči, with help from Klimenti and Piperi, destroyed the army of Süleyman Pasha twice, took over Medun and got their hands of large quantities of weapons and equipment.[10] In 1689, an uprising broke out in Piperi, Rovca, Bjelopavlići, Bratonožići, Kuči and Vasojevići, while at the same time an uprising broke out in Prizren, Peć, Priština and Skopje, and then in Kratovo and Kriva Palanka in October (Karposh's Rebellion).[13] In 1694 the Kuči allied themselves with the Hoti in yet another uprising against the Ottomans. Throughout the 18th century, the Kuči fought alongside the Vasojevići, Hoti, and Klimenti.

18th century

In 1774, in the same month of the death of Šćepan Mali,[14] Mehmed Pasha Bushati attacked the Kuči and Bjelopavlići,[15] but was subsequently decisively defeated and returned to Scutari.[14] Bushati had broken into Kuči and "destroyed" it; the Rovčani housed and protected some of the refugee families.[16]

In 1794, the Kuči and Rovčani were devastated by the Ottomans.[16]

19th century

The Ottoman increase of taxes in October 1875 sparked the Great Eastern Crisis, which included a series of rebellions, firstly with the Herzegovina Uprising (1875–77), which prompted Serbia and Montenegro declaring war on the Ottoman Empire (see Serbian–Ottoman War and Montenegrin–Ottoman War) and culminated with the Russians following suit (Russo-Turkish War). In Kuči, chieftain Marko Miljanov Popović organized resistance against the Ottomans and joined forces with the Montenegrins. The Kuči, identifying as a Serb tribe, asked to be united with Montenegro.[17] After the Berlin Congress, Kuči was included into the borders of the Principality of Montenegro.

At the Battle of Novšiće, following the Velika attacks (1879), the battalions of Kuči, Vasojevići and Bratonožići fought the Albanian irregulars under the command of Ali Pasha of Gusinje, and were defeated.

Anthropology

Old Kuči

The Old Kuči (Stari kuči/Стари кучи, Starokuči/Старокучи) was a community of a larger number of clear and composite brotherhoods (clans), in relation to the Drekalovići who claimed ancestry from one ancestor.[18] J. Erdeljanović found, in the Old Kuči, very noticeable instances of the merging of various diverse brotherhoods into one.[18] The merging was so finalized that it was hard for him to mark off the parts of those composite brotherhoods, "even the searching in that direction was also encountered in the sensitivity of individuals".[18] With the arrival of the Drekalovići, the old families called themselves "Old Kuči".[19] Of the settled brotherhoods of the Old Kuči, the Mrnjavčići are the most notable and the representatives of Old Kuči.[19] The Mrnjavčići, the largest brotherhood of Old Kuči, numbered 330 households in 1941.[20] All Old Kuči have the slava of Mitrovdan (St. Demetrius).

J. Erdeljanović wrote down data from all over Kuči, the most intricate from Kržanj, Žikoviće, Kostroviće, Bezihovo, Kute, Podgrad and Lazorce. All of these narratives agree that the Mrnjavčići brotherhood descend from Gojko, the brother of King Vukašin.[19] Gojko's descendants were forced to flee Skadar with the Ottoman invasion, and settled in Brštan.[19]

Drekalovići

The Drekalovići, also called "New Kuči" (Novi kuči), descend from Drekale, who settled Kuči in the second half of the 16th century. There are several stories on his origin: he was either a Mrnjavčić or the grandson of Skanderbeg. According to Mariano Bolizza (1614), Lale Drekalov and Niko Raičkov held 490 houses of the Chuzzi Albanesi ("Albanian Kuči", a village of predominantly Roman Catholic religion), with 1,500 soldiers, described as "very war-like and courageous". The Drekalovići, the largest brotherhood of Kuči, numbered close to 800 households in 1941, roughly half of all of Kuči.[20]

Zatrijebač

Zatrijebač (Albanian: Triesh) is a sub-region of Kuči, located in the "Kuči frontier" (Kučka Krajina), which also compose Orahovo, Koći and Fundina.[21]

The historical tribe of Zatrijebač, as well as Hoti, claim descendance from a certain Keq Preka.[22]

Trieshi was known for starting an Albanian highlander uprising against the Ottomans in 1907 with the victory in the Battle of Lemaja, fought at the Cemi River, in which 150 Trieshjan participated. According to the locals, the only thing separating the two forces was a bridge over Cemi. Other battles that followed in the region include the Battle of Deçiq (1911).

Descendants of Zatrijebač families mostly inhabit the town of Tuzi or the capital Podgorica, while many others have migrated to the United States.

Intertribal relations

It is also believed through folk telling that Grča Nenadov of Old Kuči had a brother, Krsto, who were the founding father of the Kastrati. Many Mrnjavčevićs crossed over to Islam, among the most notable the Ganići in Rožaje and Radonjičići (today Radončić) in Gusinje.

Demographics

There are over 15,000 residents in Kuči, with over 3,000 homes. Two major ethnic groups inhabit the region: ethnic Montenegrins and ethnic Serbs (see Montenegrin Serbs), though these may be regarded as one, as some families may politically be split between the two, i.e. with one brother opting for a Montenegrin identity and another a Serb. Most of the inhabitants are followers of the Serbian Orthodox Church, while a minority are Muslims by nationality. There is an enclave of Roman Catholic Albanians in the village of Koći (Koja in Albanian).

Christian Orthodox residents used to be split into two distinct groups: Old Kuči ("Starokuči") and Drekalovićs/New Kuči. The Old Kuči is generally seen as being of Serb descent and are native or have settled in the area at the time of the Serbian Empire in the 14th century. The New Kuči (generally referred to as "Drekalovići") are a large group of clans (bratstva) that were formed after the 17th century and share a legendary ancestor - Drekale.

The Islamization of Kuči has made a minority of inhabitants declaring as simply Montenegrins or Muslims by nationality and Bosniaks although they trace the same origin with that of their Christian brethren.

People

- born in Kuči

- Lale Drekalov, chieftain of the Kuči tribe, Drekale's son

- Iliko Lalev, chieftain of tribe, succeeded his father Lale

- Radonja Petrović, vojvoda (duke) of the Kuči tribe.[23]

- Marko Miljanov (1833–1901), clan chief, Montenegrin general, and writer.

- Mihailo Ivanović (1874–1949), Montenegrin politician

- Novak Milošev Vujadinović, standard-bearer

- Mitar Laković, commander of the Montenegrin army at Shkodra

- Šćepo Spaić, Montenegrin army general

- Milisav Drakulović, Orthodox priest

- Pero Ivanović, Orthodox priest

- Božo Vujosević, Orthodox priest

- Đoko Prelević, national hero

- Ljubica Popović, Partisan

- Bogdan Vujošević, Partisan

- Milija Rašović, Partisan

- Dragiša Ivanović, Partisan

- Dragiša Ivanović, Partisan

- Božina Ivanović, Yugoslav statesman

- Branimir Popović, actor

- Branislav Milačić, Montenegrin football coach

- Duško Vujošević, a basketball coach

- Dejan Radonjić, former basketball player and current coach

- Branislav Prelević, former Serbian and Greek basketball player

- Aleksandar Vujošević, former basketball player and member of Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro

- Đorđe Božović "Giška", notable Serbian gangster and paramilitary leader

- Ratko Đokić "Kobra", Serbian-Swedish Mob boss

- Branko Rašović, former Montenegrin football player[24]

- Bogdan Milić, Montenegrin footballer

- Miroslav Vujadinović, Montenegrin footballer

- Ante Miročević, former Montenegrin footballer

- Vesna Milačić, Montenegrin singer and songwriter

- Marina Kuč, Montenegrin swimmer

- Suzana Lazović, Montenegrin handball player

- by descent

- Vasa Čarapić (1768–1806), Serbian revolutionary

- Pavle Delibašić, Serbian footballer

- Mladen Nelević, Serbian actor

- Evgenije Popović, Montenegrin politician and journalist

- Vuk Rašović, Serbian former football player and current manager of Partizan Belgrade, son of Branko Rašović

Annotations

- ^ The name Kuči, as similar related toponym Kučevo (in northeastern Serbia), is etymologically unclear.[25] It might be Old Slavic *kučь, meaning Eurasian bittern (sr. bukavac), or *kuti, occupational term for "minting, smithing" (sr. kovati, pl. kuć), similar to Kovač ("smith").[25] It is found in Old Slavic (Old Serbian Коучево), in medieval Serbia, and also in medieval Poland as Kucz and Kuczów.[25] A non-Slavic origin has been theorized as well; linguists P. Skok suggested Latin *cocceus, while V. Stanišić noted similar Romanian cuci ("mountains").[25] The theory of a connection to Albanian kuç ("jug", sr. krčag) is semantically unconvincing.[25] In Albanian, the word kuq means "red",[26] which Vatro Murvar believes is the etymological origin.[27]

References

- 1 2 Petrović 1981, p. 23.

- ↑ Život i djelo Marka Miljanova Popovića: zbornik radova. Kulturno-prosvjetna zajednica. 1992.

а остали Кучи потичу, по М. Миљанову, од Мрњавчевића.1 Грча Ненадин (Ненад Гојков а Гојко Мрњавчевић) доселио је сматра војвода,

- ↑ Erdeljanović 1907, pp. 164–165

- ↑ Radovan Samardžić (1892). Istorija srpskog naroda: Doba borbi za očuvanje i obnovu države 1371-1537 (in Serbian). Srpska knjiiževna zadruga. p. 426.

- ↑ Srpski etnografski zbornik. 27-28. Akademija. 1923. p. 51.

Стари Кучи су се често тукли са старим Грудама. Кучи су били јачи, па су их пљачкали и отимали им стоку. Ако би у сукобу погинуо макар само један'\'Куч, а Грудама колико, Кучи су долазили, па их пљачкали и цијело племе кажњавали.

- 1 2 Vasić 1990.

- 1 2 Petrović 1981, p. 24.

- ↑ Elsie, Robert. Early Albania: A Reader of Historical Texts, 11th-17th Centuries. p. 155.

- ↑ Elsie, p. 152

- 1 2 3 Mitološki zbornik. Centar za mitološki studije Srbije. 2004. pp. 24, 41–45.

- ↑ Kulišić, Špiro (1980). O etnogenezi Crnogoraca (in Montenegrin). Pobjeda. p. 41. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Марко Миљанов (1904). Племе Кучи у народној причи и пјесми.

а Кучи су се, јамачно под повољнијем условима, измирили између 1614. и

- ↑ Belgrade (Serbia). Vojni muzej Jugoslovenske narodne armije (1968). Fourteen centuries of struggle for freedom. The Military Museum. p. xxviii.

- 1 2 Zapisi. Cetinjsko istorijsko društvo. 1939.

Истога мјесеца кад је Шћепан погинуо удари на Куче везир скадарски Мехмед - паша Бушатлија , но с великом погибијом би сузбијен и врати се у Скадар .

- ↑ Летопис Матице српске. У Српској народној задружној штампарији. 1898.

Године 1774. везир скадарски Мехмед паша Бушатлија ударио је на Куче и Бјелопавлиће, који позваше у помоћ Црногорце те произиђе због овога међу Црном Гором и Арбанијом велики бој и Арбанаси су се повукли ...

- 1 2 Mirko R. Barjaktarović (1984). Rovca: (etnološka monografija. Akad. p. 28.

- ↑ Zapisi; Glasnik cetinjskog istorijskog društva. 1935.

Комисија је била десет дана у Кучима и добила увјерење, да су сви Кучи једно, српско племе, да су њима, као једној породици измијешане земље и куће, да сви Кучи од Мораче до Цијевне имају своје комунице, заједничке пашњаке, једном ријечи, да је Куче немогуће подијелити. Кучи из Кучке крајине молили су сами комисију, исто као и Мркојевићи, да их не цијепају на двоје, но на једно придруже Црној Гори. Према свој овој јасности, комисија је била везана изричним наређењем берлинског уговора, да се Кучка крајина остави Турској, на што је конгрес непознавањем одношаја био заведен. Црногорски комесари из разлога, што су Кучи српско племе, што их је немогућно раздијелити, што је сам конгрес истакао начело, да се новом границом српско од арбанашкога племена одвоји — предложили су комисији линију, ...

- 1 2 3 Mihailo Konstantinović (1953). Анали правног факултета у Београду: тромесечни часопис за правне и друштвене науке. 1–2. p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Etnografski institut (1907). Srpski etnografski zbornik. 8. Akademija. p. 125–126.

- 1 2 Mihailo Petrović (1941). Đerdapski ribolovi u prošlosti i u sadašnjosti. 48. Izd. Zadužbine Mikh. R. Radivojeviča. p. 4.

- ↑ Sabrana djela, Volume 5. Grafički zavod. 1967. p. 30.

... дана позваће Марко, раније спомену- тога, Јуса Мучина из Подгорице, који је послије био поглавар над Кучком Крајином (Орахово, За- тријебач, Коће и Фундина). Јусо дође у Дољане. Ту је Марко тражио да му ваљадне Кучима,

- ↑ The Tibes of Albania,History, Society and Culture. Robert Elsie. p. 49.

- ↑ Vladimir Ćorović (13 January 2014). Istorija srpskog naroda. eBook Portal. pp. 562–. GGKEY:XPENWQLDTZF.

- ↑ sr:Бранко Рашовић

- 1 2 3 4 5 Loma, Aleksandar (2013). La toponymie de la charte de fondation de Banjska: Vers la conception d’un dictionnaire des noms de lieux de la Serbie medievale et une meilleure connaissance des structures onomastiques du slave commun. Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti. p. 127. ISBN 978-86-7025-621-7.

- ↑ Petrović 1981, p. 20.

- ↑ Murvar, Vatro (1989). Nation and Religion in Central Europe and the Western Balkans: The Muslims in Bosna, Hercegovina, and Sandžak: a Sociological Analysis. FSSSN Colloquia and Symposia, University of Wisconsin. p. 103.

Sources

- Dučić, Stevan (1931). Pleme Kuči - život i običaji. CID.

- Erdeljanović, Jovan (1907). Кучи, племе у Црној Гори: етнолошка студија. Српска краљевска академија.

- Jokanović, Miljan Milošev (1995). ПЛЕМЕ КУЧИ — ЕТНИЧКА ИСТОРИЈА. Belgrade: НИП „Књижевне новине-комерц, ДД.

- Miljanov, Marko (1904). Племе Кучи у народној причи и пјесми.

- Petrović, Rastislav V. (1981). Pleme Kuči: 1684-1796. Narodna knjiga.

- Rašović, Marko B. (1963). Pleme Kuči : etnografsko-istorijski pregled. Štampa zavod za izradu novčanica Narodne banke.

- Vasić, Milan (1990), Etnički odnosi u jugoslovensko-albanskom graničnom području prema popisnom defteru sandžaka Skadar iz 1582/83. godine