Kresna–Razlog Uprising

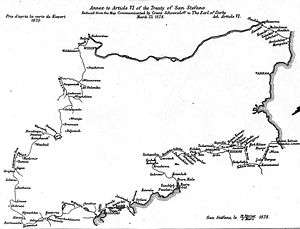

The Kresna–Razlog Uprising (Bulgarian: Кресненско-Разложко въстание, Kresnensko-Razlozhko vastanie) was a Bulgarian uprising against the Ottoman rule,[1][2][3] predominantly in the areas of Kresna and Razlog in late 1878 and early 1879. It broke out following the protests and spontaneous opposition to the decisions of the Congress of Berlin, which, instead of ceding the Bulgarian-populated parts of Macedonia to the newly reestablished Bulgarian suzerain state per the Treaty of San Stefano, returned them to Ottoman control.[4] It was prepared by the "Edinstvo" Committee.[5]

Prelude to the Uprising

The revolutionary circles in Bulgaria concurred at once with the idea of inciting an upspring in Macedonia. On 29 August 1878, a meeting of representatives from the Bulgarian revolutionaries was convened in the town of Veliko Tarnovo in order to implement the plan. This meeting resulted in the creation of a committee called Edinstvo (Unity). The initiative for this belonged to Lyuben Karavelov, Stefan Stambolov and Hristo Ivanov. The task of this new committee was to establish similar committees throughout Bulgaria, to maintain strict contact with them, and work toward the same end: "unity of all the Bulgarians" and the improvement of their present political situation.[6]

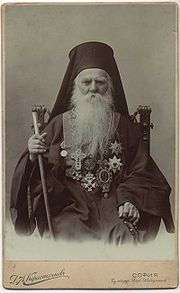

Soon after Edinstvo was formed in Tarnovo, steps were taken to spread it to all towns in Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia and to Russia and Romania as well. People were also sent to Macedonia to personally acquaint themselves with the situation there. Some were also sent to meet with Nathanael, the Ohrid bishop. He was to be told the aim and the task of Edinstvo. Meanwhile, Nathanael was already in the middle of preparations for armed activities in Macedonia. He made his way to Kyustendil to meet with the well-known haiduk leader, Ilyo Voyvoda and his rebels. At this meeting it was decided that Natanail should take over leadership of the hajduk bands. At the same time, Nathanael was able to establish an Edinstvo headquarters in the Kyustendil, one in Dupnitsa and another in Gorna Dzhumaya.[7][8] The concrete aims of the leaders and organizers of the Kresna–Razlog Uprising were to revoke the decisions of the Berlin Congress, to liberate the regions inhabited by Bulgarian population, and to unite with the free Principality of Bulgaria. By these reasons Metropolitan Nathanael of Ohrid wrote to Petko Voyvoda: "...As it is very necessary that you meet Dimitar Pop Georgiev - Berovski, who is in Gorna Dzhumaya and is the leader of the defenders of the people in these border areas, in order to discuss a very important matter to the benefit of all Bulgarians, whom the Berlin Congress has again left under Turkish tyrannical rule..."[9]

In September 1878, the Rila Monastery hosted a critical meeting attended by Metropolitan Nathanael of Ohrid, Dimitar Pop Georgiev - Berovski, Ilyo Voyvoda, Mihail Sarafov, the voivode Stoyan Karastoilov and other high-ranking figures. The conference led to the formation of an organized insurrectional staff headed by Berovski. The Edinstvo ("Unity") Committee from Sofia aided the insurrectionsts with two detachments, one led by the Russian Adam Kalmykov and the other by the Pole Luis Wojtkiewicz. The aim of "Edinstvo Committees" was "...discussing how to help our brothers in Thrace and Macedonia, who will henceforth be separated from Danubian Bulgaria by virtue of the decisions of the Berlin Congress..." Stefan Stambolov and Nikola Obretenov suggested the appointment of apostles who would organize the uprising among the masses, but it was decided that only the areas closest to the Principality of Bulgaria would revolt, with a view to detaching them from the Ottoman Empire and joining them to Bulgaria.[10][11]

Uprising

Early at dawn on October 5, 1878, 400 insurgents attacked the Turkish army unit stationed at the Kresna Inns and after a battle lasting 18 hours they succeeded in crushing its resistance. This attack and this first success marked the beginning of the Kresna–Razlog Uprising. In the battles that followed, the insurgents succeeded in liberating 43 towns and villages and in reaching Belitsa and Gradeshnitsa to the south. To the south-west they established their sway over almost the entire Karshijak region, while to the south-east the positions of the insurgents were along the Predela, over the town of Razlog. In addition to the direct military operations of the insurgents, there were separate detachments operating in the south and to the west in Macedonia. There were also disturbances, and delegations were sent to the headquarters of the Uprising with requests for arms and for aid. The headquarters of the Uprising, which was organized in the course of the military operations, was headed by Dimiter Popgeorgiev. Elders’ Councils were also set up, as well as local police organs of the revolutionary government who were assigned certain administrative functions in the liberated territories.

The Edinstvo Committee in the town of Gorna Dzhoumaya played an important part in organizing, supplying and assisting the Uprising. The Committee was headed by Kostantin Bosilkov, who was born in the town of Koprivshtitsa and who had worked for many years as teacher in the Macedonia region. The main goal of the armed struggle though, was expressed most clearly in the letter of the Melnik rebels of December 11, 1878, which they sent to the chief of the Petrich police: “...We took up the arms and will not leave them until we get united with the Bulgarian Principality... ” [12] This aim was also expressed in the appeal launched by the insurgents on November 10, 1878, which read: “...And so, brothers, the time has come to demonstrate what we are, that we are a people worthy of liberty, and that the blood of Kroum and Simeon is still flowing in our veins; the time has come to demonstrate to Europe that it is no easy task when a people wants to cast away darkness...” [13] During the military operations in the Kresna region, an uprising broke out on November 8, 1878, in the Bansko-Razlog valley. The detachment of volunteers from Moesia, led by Banyo Marinov, a revolutionary and volunteer from the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), played an important part in that uprising. It was promptly joined by scores of local insurgents and, after a fierce skirmish, it succeeded in liberating the town of Bansko. The setbacks in the autumn of 1878 led to a new organization of the leading body of the Uprising and to the adoption of new tactics. Efforts were now directed toward the setting up of a Central Committee which was to take over the leadership of the Uprising, as well as to organize an uprising in the interior of Macedonia in the spring of 1879. The detachment which crossed into Macedonia in May 1879 could not fulfill its task due to the lack of preliminary organization. These events marked the end of the Kresna–Razlog Uprising.

Significance and consequences

In this manner the Kresna–Razlog Uprising was left without its expected and most reliable reserve – Russia’s military, diplomatic and political support, in addition to its being against the interests of Austria-Hungary and Britain. Russia was exhausted both financially and militarity, and she adopted a firm course of adhering to the decisions of the Berlin Congress in relation to Macedonia. Her strategic aim lay in the preservation of the Bulgarian character of Eastern Roumelia. It encountered yet another strong adversary - the military and political machine of the Ottoman state.

The representatives of the Provisional Russian Administration in Principality of Bulgaria, who sympathised with the struggle, were reprimanded by the Russian Emperor in person. These were the decisive reasons for Its failure, parallel with reasons of internal and organizational character.[14] Typical for the uprising was the scale participation of volunteers - Bulgarians of all parts of the country. Some figures as an illustration: 100 volunteers from Sofia, 27 from Tirnovo, 65 from Pazardzhik, 19 from Troyan, 31 from Pleven, 74 from Orhanye, 129 from the Plovdiv district, 17 from Provadia, 30 from Eastern Rumelia and others. A large number of insurgents and leaders of different parts of Macedonia also participated in the uprising. After the Upspring some 30,000 refugees fled to Bulgaria.[15] The failure of the uprising lead to the attention of the Bulgarian political and strategic leaders to liberation of the other parts of the Bulgarian territories and to other main strategic objective - unification of the Principality of Bulgaria and Eastern Roumelia, the later being under Sultans power, but still having a large autonomy. Macedonia and Thrace should have to wait.

Controversy

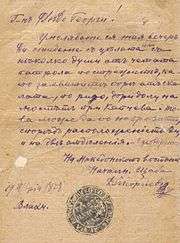

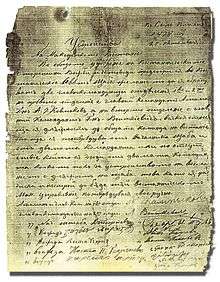

Like most 19th century events and developments in the region of Macedonia, the issue on national and ethnic affiliations of the insurgents is contested in the Republic of Macedonia. The uprising is regarded as ethnic Macedonian by the historians from Rep. of Macedonia. They support their perception of the existence of a Macedonian ethnicity at that time with the Proclamation of Kresna Uprising, which is considered а forged document by Bulgarian scientists, pointing out for example the usage of anachronistic language and contradictions with other documents.[16] Bulgarians argued about existing of original "Temporary rules about the organisation of the Macedonian Upspring" prepared from Stefan Stambolov and Nathanael of Ohrid.[17]

Macedonian historians argue also that the use of the word "Bulgarian" in Ottoman Macedonia does not refer to ethnicity, and that it had been synonymous with "Christian" or "peasant". Bulgarian historians argue that the term "Macedonian" has never been used in an ethnic but in regional sense, similar to the regional term "Thracian"[18] and note that no distinction between a "Macedonian Bulgarians", "Bulgarians" and "Slavs" existed at that time pointing to the correspondence of the insurgents of the upspring with the Bulgarian committees "Edinstvo" - (Unity).[19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ A concise history of Bulgaria, Cambridge concise histories, R. J. Crampton, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 85 ISBN 0-521-61637-9.

- ↑ Who Are the Macedonians? by Hugh Poulton, page 49, Indiana University Press, 2000 ISBN 1-85065-534-0

- ↑ Stefan Stambolov and the emergence of modern Bulgaria, 1870-1895, Duncan M. Perry, Duke University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8223-1313-8, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Ethnic rivalry and the quest for Macedonia, 1870-1913, Vemund Aarbakke, East European Monographs, 2003, ISBN 0880335270, p. 56.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810855658, p. 122.

- ↑ The Macedonian Question - Origin and Development, 1878-1941 Dimiter Minchev, Ph.D. Sofia, 2002.

- ↑ An appeal from the Macedonian Bulgarians to the Great Powers begging them not to sever them from Bulgaria, their common motherland. May 20th, 1878

- ↑ A letter from Nathanail, Bishop of Ohrid, to I. S. Aksakov on the need to preserve the Bulgarian people's national integrity. July 24th, 1878

- ↑ A letter of bishop Nathanail to Petko Voyvoda about the organization of the struggle of the Bulgarians who have remained under Turkish domination, Sep. 25th, 1878

- ↑ Protocol on the formation and the rights of the Insurgents' Commanding Staff of the Kresna-Razlog Uprising in Vlahi village October 20th, 1878

- ↑ A letter from Adam Kalmikov and Dimiter P. Georgiev to the Edinstvo committee in Gorna Djoumaya,in which they inform them of the tasks of the newly formed insurgents' police to the liberated villages and of the spreading of the uprising.

- ↑ The Macedonian Question - Origin and Development 1878-1941. Colonel Dimiter Minchev, Ph.D. (Sofia, 2002)

- ↑ The Kresna-Razlog Uprising of 1878. Sofia, 1970, p. 135.

- ↑ THE KRESNA-RAZLOG UPRISING 1878-1879 (Summary) DOYNO DOYNOV. Bulgarian Academy of Science 1978.

- ↑ Дойнов, Д. Кресненско-Разложкото въстание..., с. 84.

- ↑ Христо Христов. Писма и оправки - По следите на една историко-документална фалшификация. (Исторически Преглед, 1983, кн. 4, с. 100—106).[Hristo Hristov. 1983. Tracking a historical documental falsification. Historical Review 4:100-106]. This source is a peer-reviewed journal published by the Institute of History at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

- ↑ Дойно Дойнов Кресненско-Разложкото въстание, 1878-1879, София 1979, с. 71, бел. 323, с. 154, с. 163-164, бел. 235

- ↑ Освобождение Болгарии. . . Т. 3, д. № 170, с. 272.

- ↑ A letter from the citizens of Gorna Djoumaya to Dossitei, Metropolitan of Samokov, announcing the setting up of Edinstvo charitable committee.

- ↑ А letter from Adam Kalmikov and Dimiter P. Georgiev to the Edinstvo committee in Gorna Djoumaya, in which they inform them of the tasks of the newly formed insurgents' police in the liberated villages and of the spreading of the uprising - October 17th, 1878

- ↑ A letter of Dimiter P. Georgiev to the Edinstvo committee in the town of Gorna Djoumaya, reporting the insurgents' first clash with the Turkish guard at the Kresna Inns - October 5th, 1878

- ↑ A call by the Bulgarian Provisional Government issued in Mount Pirin to the Bulgarians and Slavs to support the uprising

- ↑ A petition by Bulgarian refugees from Macedonia following the Kresna-Razlog Uprising, to W. G. Palgrave, UK Consul General in Sofia, with a plea to be liberated from Turkish domination

- ↑ Letter of the insurgent villages in the Melnik area in reply to the Petrich district governor December 11th, 1878

- ↑ Excerpts from the Circular Letter of the Central Bulgaro-Macedonian Committee in Kyustendil on the decision to organize an uprising in Macedonia May 6th, 1879

Sources

- Дойно Дойнов. Кресненско-Разложкото въстание, 1878-1879 Принос за неговия обхват и резултати, за вътрешните и външнополитическите условия, при които избухва, протича и стихва. (Издателство на Българската Академия на науките. София, 1979) (Doyno Doynov. Kresna-Razlog uprising 1878-1879: On its scope and results, internal and external political circumstances in which it starts, continues, and ends. Sofia. 1979. Published by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences)

- BULGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Institute of History Bulgarian Language Institute - MACEDONIA, DOCUMENTS AND MATERIALS. Sofia 1978

- БАЛКАНСКИТЕ ДЪРЖАВИ И МАКЕДОНСКИЯТ ВЪПРОС - Антони Гиза.(превод от полски - Димитър Димитров, Македонски Научен Институт, София, 2001)