Korean Wave

| Korean Wave | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 韓流 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 韩流 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 한류 | ||||||

| Hanja | 韓流 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 韓流 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Nepali name | |||||||

| Nepali |

कोरियाली लहर Kōriyālī lahara | ||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||

| Vietnamese | 韓流 Hàn lưu | ||||||

The Korean Wave (Hangul: 한류; Hanja: 韓流; RR: Hallyu; MR: Hallyu, ![]() listen , a neologism literally meaning 'flow of Korea') is the increase in global popularity of South Korean culture since the 1990s.[2][3][4] First driven by the spread of K-dramas and K-pop across East, South and Southeast Asia during its initial stages, the Korean Wave evolved from a regional development into a global phenomenon, carried by the Internet and social media and the proliferation of K-pop music videos on YouTube.[5][6][7][8][9]

listen , a neologism literally meaning 'flow of Korea') is the increase in global popularity of South Korean culture since the 1990s.[2][3][4] First driven by the spread of K-dramas and K-pop across East, South and Southeast Asia during its initial stages, the Korean Wave evolved from a regional development into a global phenomenon, carried by the Internet and social media and the proliferation of K-pop music videos on YouTube.[5][6][7][8][9]

Since the turn of the 21st century, South Korea has emerged as a major exporter of popular culture and tourism, aspects which have become a significant part of its burgeoning economy. The growing popularity of Korean pop culture in many parts of the world has prompted the South Korean government to support its creative industries through subsidies and funding for start-ups, as a form of soft power and in its aim of becoming one of the world's leading exporters of culture along with Japanese and British culture, a niche that the United States has dominated for nearly a century.[10][11]

Much of the success of the Korean Wave owes in part to the development of social networking services and online video sharing platforms such as YouTube, which have allowed the Korean entertainment industry to reach a sizable overseas audience. Use of these mediums in facilitating promotion, distribution and consumption of various forms of Korean entertainment (and K-pop in particular) has contributed to their surge in worldwide popularity since the mid-2000s.[11][12]

Overview

The Korean term for the phenomenon of the Korean Wave is Hanryu (Hangul: 한류), more commonly romanized as Hallyu. The term is made of two root words; han (韓) roughly means 'Korean', while liu or ryu (流) means 'flow' or 'wave',[13] referring to the diffusion of Korean culture.

This term is sometimes applied differently outside of Korea; for example, overseas, Hallyu drama is used to describe Korean drama in general, but in Korea, Hallyu drama and Korean drama are taken to mean slightly different things. According to researcher Jeongmee Kim, the term Hallyu is used to refer only to dramas that have gained success overseas, or feature actors that are internationally recognised.[14]

The Korean Wave encompasses the global awareness of different aspects of South Korean culture including film and television (particularly 'K-dramas'), K-pop, manhwa, the Korean language, and Korean cuisine. Some commentators also consider traditional Korean culture in its entirety to be part of the Korean Wave.[15] American political scientist Joseph Nye interprets the Korean Wave as "the growing popularity of all things Korean, from fashion and film to music and cuisine."[16]

History

Background

An early mention of Korean culture as a form of soft power can be found in the writings of Kim Gu, leader of the Korean independence movement and president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. Towards the end of his autobiography, he writes:

...I want our nation to be the most beautiful in the world. By this I do not mean the most powerful nation. Because I have felt the pain of being invaded by another nation, I do not want my nation to invade others. It is sufficient that our wealth makes our lives abundant; it is sufficient that our strength is able to prevent foreign invasions. The only thing that I desire in infinite quantity is the power of a noble culture. This is because the power of culture both makes us happy and gives happiness to others...— Kim Gu, Excerpt from Baekbeomilji, March 1st, 1948

1950-1995: Foundations of cultural industry

Following the Korean War (1950–53) and the Korean Armistice Agreement signed in 1953, South Korea experienced a period of rapid economic growth known as the Miracle on the Han River.

In the film industry, screen quotas were introduced in South Korea during Park Chung-hee's presidency to restrict the number of foreign films shown in cinemas.[17] These were intended to prevent competition between domestic films and foreign blockbuster movies.[18] However, in 1986, the Motion Pictures Exporters Association of America filed a complaint to the United States Senate regarding the regulations imposed by the South Korean government,[19] which was compelled to lift the restrictions. In 1988, Twentieth Century Fox became the first American film studio to set up a distribution office in South Korea, followed by Warner Brothers (1989), Columbia (1990), and Walt Disney (1993).[20]

By 1994, Hollywood's share of the South Korean movie market had reached a peak of around 80 percent, and the local film industry's share fell to a low of 15.9 percent.[21] That year, president Kim Young-sam was advised to provide support and subsidies to Korean media production, as part of the country's export strategy.[22] According to South Korean media, the former President was urged to take note of how total revenues generated by Hollywood's Jurassic Park had surpassed the sale of 1.5 million Hyundai automobiles; with the latter a source of national pride, this comparison reportedly influenced the government's shift of focus towards culture as an exportable industry.[23] At this time, the South Korean Ministry of Culture set up a cultural industry bureau to develop its media sector, and many investors were encouraged to expand into film and media. Thus, by the end of 1995 the foundation was laid for the rise of Korean culture.[23]

1995-1999: Development of cultural industry

In July 1997, the Asian financial crisis led to heavy losses in the manufacturing sector, prompting a handful of businesses to turn to the entertainment sector.[24]

According to The New York Times, South Korea began to list restrictions on cultural imports from its former colonial ruler Japan in 1998. With an aim of tackling an impending "onslaught" of Japanese movies, anime, manga, and J-pop, the South Korean Ministry of Culture made a request for a substantial budget increase, which allowed the creation of 300 cultural industry departments in colleges and universities nationwide.[25]

In February 1999, the first local big-budget film, Shiri, was released and became a major commercial success. It grossed over US$11 million, surpassing the Hollywood blockbuster Titanic.[26][27]

1999-2010: Korean Wave in Asia

Around this time, several Korean television dramas were broadcast in China. On November 19, 1999, one of China's state-controlled daily newspapers, the Beijing Youth Daily, published an article acknowledging the "zeal of Chinese audiences for Korean TV dramas and pop songs".[28] In February 2000, S.M. Entertainment's boy-band H.O.T. became the first modern K-pop artist to give an overseas performance, with a sold-out concert in Beijing.[29] As the volume of Korean cultural imports rapidly increased, China's State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television responded with a decision to restrict and limit the number of Korean TV dramas shown to Chinese audiences.[30]

However, several other countries in East Asia were also experiencing a growth in the popularity of Korean dramas and pop songs. In 2000 in the Indian state of Manipur, where Bollywood movies were banned by separatists, consumers gradually turned their attention to Korean entertainment.[31] According to Agence France-Presse, Korean phrases were commonly heard in the schoolyards and street markets of Manipur.[32] Many Korean dramas and films were smuggled into Manipur from neighbouring Burma, in the form of CDs and DVDs.[31] In 2002, BoA's album Listen to My Heart became the first album by a Korean musician to sell a million copies in Japan.[33]

At the same time that Hallyu was experiencing early success, there was an equally noticeable growth in cultural imports from Taiwan, also one of the Four Asian Tigers. The 2001 Taiwanese drama Meteor Garden (an adaptation of the Japanese shōjo manga series Boys Over Flowers) was popular over the continent: it became the most-watched drama series in Philippine television history, garnered over 10 million daily viewers in Manila alone, and catapulted the male protagonists from Taiwanese boyband F4 to overnight fame,[34][35][36] spawning a sequel and later adaptations by other networks (including Korean channel KBS in 2009.)

On June 8, 2001, Shinhwa's fourth album Hey, Come On! was released to success over Asia. The group became particularly popular in China and Taiwan.

In 2002, Winter Sonata (produced by Korean channel KBS2) became the first drama to equal the success of Meteor Garden, attracting a cult following in Asia. Sales of merchandise, including DVD sets and novels, surpassed US$3.5 million in Japan.[37] This drama marked the initial entrance of the Korean Wave in Japan.[38][39][40][41][42] In 2004, former Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi noted that the male protagonist of the drama was "more popular than I am in Japan".[43] Other Korean dramas released in subsequent years such as Dae Jang Geum (2003) and Full House (2004) saw comparable levels of success.[44]

Since 2002, television programming trends in Asia began to undergo changes as series from both South Korea and Taiwan began to fill prime time slots previously reserved for Hollywood movies.[45]

The breakthrough for K-pop came with the debuts of TVXQ (2003), SS501 (2005), Super Junior (2005), and other artists hailed by a BBC reporter as "household names in much of Asia".[46] In 2003, South Korean girl group Baby V.O.X. released a Chinese single entitled "I'm Still Loving You" and topped various music charts in China, making a huge fanbase there. Both "I'm Still Loving You" and their subsequent Korean single "What Should I Do" also charted in Thailand.

Meanwhile, the popularity of Korean television continued to spread across the continent. Reports about Asian women travelling to South Korea to find love, inspired by Korean romance dramas, began to appear in the media, including in the Washington Post.[47]

In Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka, Korean dramas began to increasingly take up airtime on TV channels in these countries with Winter Sonata and Full House credited to igniting the interest in Korean pop culture in these countries. Korean fashion and hairstyles became trendy amongst youth in Nepal and led to a Korean language course boom in the country which has persisted to today. Korean cuisine experienced a surge of popularity in Nepal with more Korean eateries opening in the country throughout the early to mid 2000s. Similarly, Korean cuisine also became popular in Sri Lanka and Bhutan with Korean restaurants opening to satisfy the demand in these countries.[48][49][50][51]

By the late 2000s, many Taiwanese musicians had been superseded by their K-pop counterparts, and although a small number of groups such as F4 and Fahrenheit continued to maintain fan bases in Asia, young audiences were more receptive to newer K-pop bands such as Big Bang and Super Junior.

2010-present: Korean Wave globally

In the United States, Korean culture and K-pop has spread outwards from Korean American immigrant communities such as those in Los Angeles and New York City.[52] However, even a few years ago there was little response from American music producers; according to the chief operating officer of Mnet Media, its employees' attempt to pitch over 300 K-pop music videos to American producers and record labels was met with a lukewarm response, there being "relationships so they would be courteous, but it was not a serious conversation".[53] Similarly, attempted US debuts by artists such as BoA and Se7en failed to gain traction. They were labeled by a CNN reporter as "complete flops".[54]

Despite this, K-pop itself and Korean television (with shows such as Jumong being particularly well received by audiences in the Muslim world) have seen increasing popularity throughout the US and elsewhere, with a dedicated and growing global fanbase,[55][56][57][58] particularly after Psy's video for "Gangnam Style" went viral in 2012-13 and was the first YouTube video to reach over a billion views. The platform of YouTube was vital in the increasing international popularity of K-pop, overriding the reluctance of radio DJs to air foreign-language songs in reaching a global audience. A CNN reporter attending KCON 2012 (a popular US K-pop convention) in Irvine, California said, "If you stop anyone here and ask them how they found out about K-pop, they found it out on YouTube."[59]

In 2012, the Korean Wave was officially mentioned by both US President Barack Obama at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies on March 26 (Full transcript at whitehouse.gov) and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon at the National Assembly of South Korea on October 30 (Full transcript at un.org).

In February 2013, Peru's vice president Marisol Espinoza was interviewed by South Korea's Yonhap News Agency and welcomed the Korean Wave to Peru.[60] That month, White House officials managing First Lady of the United States Michelle Obama's Twitter account revealed that they had gathered Napa cabbage from the South Lawn to make kimchi, a traditional Korean pickled cabbage dish.[61][62] As an editor of Esquire magazine pointed out, this was considered perplexing because it "skews so far from the White House's usual fare".[63] This news came shortly after it was reported that sales of Korean cuisine at the British supermarket chain Tesco more than doubled,[64] and there were further mainstream reports of the Korean Wave in Germany and France.[65][66]

That year, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Aung San Suu Kyi made her first visit to South Korea and attended a dinner with several actors including Ahn Jae-wook, whom Suu Kyi reportedly invited because of his resemblance to her assassinated father Aung San.[67]

On February 25, 2013, South Korea's newly elected president Park Geun-hye delivered her inauguration speech, where she promised to build a nation that "becomes happier through culture," and to foster a "new cultural renaissance" that will transcend ethnicity and overcome ideologies because of its "ability to share happiness".[68] According to The Korea Times, one of Park Geun-hye's main priorities as president will be to allocate at least 2 percent of the national budget to further develop South Korea's cultural industry and to seek more cultural exchanges with North Korea.[69]

South Korea has experienced recent growth in the tourism sector, welcoming over 12 million visitors in 2013, with 6 million tourists from China alone.[70] However, that year, a state survey of 3,600 respondents from over the world found that over 66% of respondents believed that the popularity of Korean culture would "subside in the next four years".[71]

Hallyu Index

State-funded trade promotion organisation KOTRA publishes an annual index measuring the reach of the Korean Wave in major countries around the world. The index is calculated by a combination of export data and public surveys. In 2015, public surveys were conducted across 8,130 people in 29 countries.[72]

The results shown below indicate the greatest popularity in Asian countries, with Indonesia and Thailand experiencing the fastest growth of those, while there is declining interest in Japan, Iran, and Mexico.

| Minority interest stage | Diffusion stage | Mainstream stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Popularity | Countries | Popularity | Countries | Popularity | Countries |

| Rapid growth | N/A | Rapid growth | |

Rapid growth | |

| Medium growth | |

Medium growth | |

Medium growth | |

| Decline | |

Decline | |

Decline | N/A |

Fan clubs

According to a 2011 survey conducted by the South Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, the total number of active members of Hallyu fan clubs worldwide was estimated at 3.3 million, based on statistics published by official fan clubs in regions where there are Korean Cultural Centers.[73] In the same year, the Korea Tourism Organization surveyed 12,085 fans of Hallyu and concluded that most fans were young adults, over 90% were female, and most were fans of K-pop.[74]

| Year | Country/ Region |

Number of Hallyu fans |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | |

1,000 | [76] |

| 2012 | |

3,000 | [77] |

| 2012 | |

5,000 | [77] |

| 2012 | |

8,000 | [78] |

| 2012 | |

20,000 | [78] |

| 2012 | |

50,000 | [79] |

| 2012 | |

60,000 | [80] |

| 2011 | |

>100,000 | [81] |

| 2013 | |

>150,000 | [82] |

| Worldwide total | |||

| Year | Fan clubs | Members | Source |

| 2011 | 182 | 3.3 million | [83] |

| 2012 | 830 | 6.0 million | [84] |

| 2013 | 987 | 9.3 million | [85] |

Foreign relations

South Korea's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Tourism (MOFAT) has been responsible for international advocacy of Korean culture. The South Korean government is involved in the organisation of concerts such as the annual K-Pop World Festival.[86]

Asia

China

In the past decade or so, many Chinese officials have expressed positivity towards Korean media and entertainment, including former President Hu Jintao[87][88] and former Premier Wen Jiabao, who was quoted by Xinhua News Agency as saying: "Regarding the Hallyu phenomenon, the Chinese people, especially the youth, are particularly attracted to it and the Chinese government considers the Hallyu phenomenon to be a vital contribution towards mutual cultural exchanges flowing between China and South Korea."[89]

A four-member research study led by Kang Myung-koo of Seoul National University published a controversial report in 2013 suggesting that Chinese viewers of Korean dramas were generally within the lower end of the education and income spectrum. This led to an angry response from Chinese fans of Korean television, with one group purchasing a full-page advertisement in the Chosun Ilbo to request an apology from the authors of the study.[90][91]

In August 2016, it was reported that China planned to ban Korean media broadcasts and K-pop idol promotions within the country in opposition to South Korea's defensive deployment of THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) missiles.[92][93][94]

Japan

The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs acknowledges that the Korean Wave in Japan has led to discussion and mutual cultural exchange between the two countries,[95] with high-profile fans of Korean television including former First Lady Miyuki Hatoyama and current First Lady Akie Abe.[96] However, remaining tension between Japan and Korea has led to instances of street protests involving hundreds of people, demonstrating against the popularity of Korean entertainment exports.[97] These protests were mostly organized by critics of Korean pop culture with the support of right-wing nationalists.[98]

Taiwan

Local broadcasting channel GTV began to broadcast Korean television dramas in the late 1990s. The shows were dubbed into Mandarin and were not marketed as foreign, which may have helped them to become widely popular during this time.[99]

Middle East and North Africa

Since the mid-2000s, Israel, Morocco, Egypt and Iran have become major consumers of Korean culture.[100][101] Following the success of Korean dramas in the Middle East, the Korean Overseas Information Service made Winter Sonata available with Arabic subtitles on several state-run Egyptian television networks. The New York Times reported that the intent behind this was to contribute towards positive relations between Arab audiences and South Korean soldiers stationed in northern Iraq.[102]

Israel and Palestine

In 2006, the Korean drama My Lovely Sam Soon was aired on Israeli cable channel Viva. Despite a lukewarm response, there followed a surge in interest in Korean television shows, and a further thirty Korean dramas were broadcast on the same channel.[103] In 2008, Yediot Aharonot, the most widely circulated daily Israeli newspaper, described the popularity of Korean dramas in Israel as a "revolution" in cultural tastes, and in 2013, popular Israeli newspaper Calcalist published a three-page cover story on how K-pop had "conquered" Israeli youth.

In 2008, a Korean language course was launched at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, offering lectures on Korean history, politics, and culture.[77]

It is hoped by some commentators that the surging popularity of Korean culture across Israel and Palestine[104] may serve as a bridge over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[77] The Hebrew University of Jerusalem reported that some Israeli and Palestinian K-pop fans see themselves as "cultural missionaries" and actively introduce K-pop to their friends and relatives, further spreading the Korean Wave within their communities.[105][106]

Egypt

Autumn in My Heart, one of the earliest Korean dramas brought over to the Middle East, was made available for viewing after five months of "persistent negotiations" between the South Korean embassy and an Egyptian state-run broadcasting company. Shortly after the series ended, the embassy reported that it had received over 400 phone calls and love letters from fans from all over the country.[107] According to the secretary of the South Korean embassy in Cairo Lee Ki-seok, Korea's involvement in the Iraq War had significantly undermined its reputation among Egyptians, but the screening of Autumn in My Heart proved "extremely effective" in reversing negative attitudes.[108]

Iran

Iran's state broadcaster, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), aired several Korean dramas during prime time slots in recent years, with this decision attributed by some to their Confucian values of respect for others, which are "closely aligned to Islamic culture",[110] while in contrast, Western productions often fail to satisfy the criteria set by Iran's Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.[111] In October 2012, the Tehran Times reported that IRIB representatives visited South Korea to visit filming locations in an effort to strengthen "cultural affinities" between the two countries and to seek avenues for further cooperation between KBS and IRIB.[112][113]

According to Reuters, until recently audiences in Iran have had little choice in broadcast material and thus programs that are aired by IRIB often attain higher viewership ratings in Iran than in South Korea; for example, the most popular episodes of Jumong attracted over 90% of Iranian audience (compared to 40% in South Korea), propelling the its lead actor Song Il-gook to superstar status in Iran.[109]

Researchers from both countries have recently studied the cultural exchanges between Silla (one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea) and the Persian Empire. The Korea Times reported that the two cultures may have been similar 1,200 years ago.[114]

| Year(s) of broadcast |

TV series | TV channel | Episodes | Television ratings |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006–07 | Dae Jang Geum | Channel 2 | 54 | 86% | [115] |

| 2007–08 | Emperor of the Sea | Channel 3 | 51 | ||

| 2008 | Thank You | Channel 5 | 16 | ||

| 2008–09 | Jumong | Channel 3 | 81 | 80–90% | [58] |

| 2009 | Behind the White Tower | Channel 5 | 20 | ||

| 2010 | Yi San | Provincial channels | 77 | ||

| 2010-11 | The Kingdom of the Winds | Channel 3 | 36 | ||

| 2011 | The Return of Iljimae | Channel 3 | 24 | ||

| 2012 | Dong Yi | Channel 3 | 60 | [112] | |

| 2014 | Hong Gil-dong | Provincial channels | 24 | ||

| 2014 | Kim Su-ro, The Iron King | Channel 3 | 32 | ||

| 2014 | Brain | Channel 5 | 20 | ||

| 2015 | Faith | Namasyesh TV | 24 | ||

| 2015 | Moon Embracing the Sun | Channel 3 | 22 | ||

| 2015 | Fermentation Family | Namasyesh TV | 24 | ||

| 2015 | Gyebaek | Namasyesh TV | 36 | ||

| 2015 | Good Doctor | Channel 2 | 20 | ||

| 2016 | Pasta | Namasyesh TV | 20 | ||

| 2016 | The Fugitive of Joseon | IRIB TV3 | 20 | ||

| 2016 | The King's Dream | Namasyesh TV | 75 |

Iraq

In the early 2000s, Korean dramas were aired for South Korean troops stationed in northern Iraq as part of coalition forces led by the United States during the Iraq War. With the end of the war and the subsequent withdrawal of South Korean military personnel from the country, efforts were made to expand availability of K-dramas to the ordinary citizens of Iraq.[116]

In 2012, the Korean drama Hur Jun reportedly attained a viewership of over 90% in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.[116] Its lead actor Jun Kwang-ryul was invited by the federal government of Iraq to visit the city of Sulaymaniyah in Kurdistan, at the special request of the country's First Lady, Hero Ibrahim Ahmed.[116]

Turkey

In February 2012, JYJ member Jaejoong was invited by the South Korean Embassy in Ankara to hold an autograph session at Ankara University.[117] Before departing for concerts in South America, Jaejoong also attended a state dinner with the presidents of South Korea (Lee Myung Bak) and Turkey (Abdullah Gül).[118]

Oceania

Australia

In March 2012, former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard visited South Korea's Yonsei University, where she acknowledged that her country has "caught" the Korean Wave that is "reaching all the way to our shores."[119]

New Zealand

In November 2012, New Zealand's Deputy Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Andrea Smith, delivered a key note address to South Korean diplomats at the University of Auckland, where she asserted that the Korean Wave is becoming "part of the Kiwi lifestyle" and added that "there is now a 4,000 strong association of K-Pop followers in New Zealand."[120]

Europe

Romania

The first Korean drama in Romania was aired on TVR in August 2009, and in the following month it became the third most popular television program in the country.[121] Since then, Korean dramas have seen high ratings and further success.[121][122]

France

The French Foreign Ministry acknowledges the status of Hallyu as a global phenomenon that is characterized by the "growing worldwide success of Korean popular culture".[123]

Germany

The German Foreign Office has confirmed that "Korean entertainment (Hallyu, telenovelas, K-Pop bands, etc) is currently enjoying great popularity and success in Asia and beyond."[124]

United Kingdom

In November 2012, the British Minister of State for the Foreign Office, Hugo Swire, held a meeting with South Korean diplomats at the House of Lords, where he affirmed that Korean music had gone "global".[125]

United States

During a bilateral meeting with South Korean President Park Geun-Hye at the White House in May 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama cited "Gangnam Style" as an example of how people around the world are being "swept up by Korean culture – the Korean Wave."[127] In August 2013, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry also affirmed that the Korean Wave "spreads Korean culture to countries near and far."[128]

United Nations

On October 30, 2012, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon delivered a speech in front of the National Assembly of South Korea where he noted how Korean culture and the Hallyu-wave is "making its mark on the world".[129]

Impact

Sociocultural

The Korean Wave has spread the influence of aspects of Korean culture including fashion, music, television programs and formats, cosmetics, games, cuisine, manhwa and beauty standards.[130][131][132]

In China, many broadcasters have taken influences from Korean entertainment programs such as Running Man; in 2014 SBS announced the Chinese version of this program, Hurry Up, Brother, which was a major hit as an example of a unique category of programs known as 'urban action varieties'.[133][134]

Korean media has also been influential throughout Asia in terms of beauty standards. In Taiwan, where the drama Dae Jang Geum was extremely popular, some fans reportedly underwent cosmetic surgery to look similar to lead actress Lee Young-ae.[135]

Political and economic

In 2012, a poll conducted by the BBC revealed that public opinion of South Korea had been improving every year since data began to be collected in 2009. In countries such as Russia, India, China and France, public opinion of South Korea turned from "slightly negative" to "generally positive".[136] This increase in 'soft power' corresponded with a surge in exports of US$4.3 billion in 2011.[137]

Korean producers have capitalised on high demand in Asia due to the popularity of Korean media, which enabled KBS to sell its 2006 drama Spring Waltz to eight Asian countries during its pre-production stage in 2004.[14]

The following data is based on government statistics:

| 2008[138] | 2009[139] | 2010[140] | 2011[140] | 2012[141] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total value of cultural exports (in USD billions) |

1.8 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 5.02 |

The following data is from the Korea Creative Contents Agency (part of the Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism) for the first quarter of the 2012 fiscal year:

| Creative Industry Sector | Total revenue (KRW) | Exports (KRW) |

|---|---|---|

| Animation[142] | ₩135.5 billion | ₩35.2 billion |

| Broadcasting[143] | ₩213.5 billion | ₩2.2 billion |

| Cartoon[144] | ₩183.2 billion | ₩4.7 billion |

| Character[142] | ₩1882.9 billion | ₩111.6 billion |

| Gaming[145] | ₩2412.5 billion | ₩662.5 billion |

| Knowledge/Information[146] | ₩2123.1 billion | ₩105.2 billion |

| Motion Picture[147] | ₩903.8 billion | ₩15.6 billion |

| Music[148] | ₩997.3 billion | ₩48.5 billion |

| Publishing[144] | ₩5284.6 billion | ₩65 billion |

Relations with North Korea

The ninth President of South Korea, Roh Moo-hyun, acknowledged the possible use of Hallyu as a tool to help to reunify the Korean Peninsula.[149] In May 2007 the television series Hwang Jini, adapted from a novel by a North Korean author, became the first South Korean production to be made available for public viewing in North Korea.[150]

With the end of the Roh Moo-hyun administration's Sunshine Policy towards North Korea and a deterioration of North-South relations, however, Hallyu media was quickly restrained by North Korean authorities, although a report published by Radio Free Asia (a non-profit radio network funded by the U.S. federal government) suggested that the Korean Wave "may already have taken a strong hold in the isolated Stalinist state".[151]

In 2010, researchers from the Korea Institute for National Unification surveyed 33 North Korean defectors and found that the impact of shows such as Winter Sonata had played a significant role in shaping the decision of the defectors to flee to the South. It was further revealed that a small number of people living close to the Korean Demilitarized Zone have been tampering with their televisions sets in order to receive signals from South Korean broadcast stations in the vicinity, while CDs and DVDs smuggled across the border with China also increased the reach of South Korean popular culture in the North.[149] In 2012, the Institute surveyed a larger group of 100 North Korean defectors. According to this research, South Korean media was prevalent within the North Korean elite. It also affirmed that North Koreans living close to the border with China had the highest degree of access to South Korean entertainment, as opposed to other areas of the country.[152] Notels, Chinese-made portable media players that have been popular in North Korea since 2005, have been credited with contributing to the spread of the Hallyu wave in the Northern country.[92][153]

In October 2012, the Leader of North Korea, Kim Jong-un, gave a speech to the Korean People's Army in which he vowed to "extend the fight against the enemy's ideological and cultural infiltration".[154] A study conducted earlier that year by an international group commissioned by the U.S. State Department came to the conclusion that North Korea was "increasingly anxious" to keep the flow of information at bay, but had little ability to control it, as there was "substantial demand" for movies and television programs from the South as well as many "intensely" entrepreneurial smugglers from the Chinese side of the border willing to fulfill the demand.[155]

—A North Korean defector interviewed by Human Rights Watch[156]

In February 2013, South Korea's Yonhap news agency reported that Psy's 2012 single "Gangnam Style" had "deeply permeated North Korea", after a mission group had disseminated K-pop CDs and other cultural goods across the China–North Korea border.[157]

On May 15, 2013, the NGO Human Rights Watch confirmed that "entertainment shows from South Korea are particularly popular and have served to undermine the North Korean government's negative portrayals of South Korea".[158]

Tourism

South Korea's tourism industry has been greatly influenced by the increasing popularity of its media. According to the Korea Tourism Organization (KTO), monthly tourist numbers have increased from 311,883 in March 1996[159] to 1,389,399 in March 2016.[160]

The Korean Tourism Organisation recognises K-pop and other aspects of the Korean Wave as pull factors for tourists,[161] and launched a campaign in 2014 entitled "Imagine your Korea", which highlighted Korean entertainment as an important part of tourism.[162][163] According to a KTO survey of 3,775 K-pop fans in France, 9 in 10 said they wished to visit Korea, while more than 75 percent answered that they were actually planning to go.[164] In 2012, Korean entertainment agency S.M. Entertainment expanded into the travel sector, providing travel packages for those wanting to travel to Korea to attend concerts of artists signed under its label.[164]

Many fans of Korean television dramas are also motivated to travel to Korea,[165] sometimes to visit filming locations such as Nami Island, where Winter Sonata was shot and where there were over 270,000 visitors in 2005.[161] The majority of these tourists are female.[166] K-drama actors such as Kim Soo-hyun have appeared in KTO promotional materials.[167]

Criticism

The Korean Wave has also been met with backlash and anti-Korean sentiment in countries such as China, Japan, and Taiwan.[168] Existing negative attitudes towards Korean culture may be rooted in nationalism or historical conflicts.[97][169]

In China, producer Zhang Kuo Li described the Korean Wave as a "cultural invasion" and advised Chinese people to reject Korean exports.[170]

In Japan, an anti-Korean comic, Manga Kenkanryu ("Hating the Korean Wave") was published on July 26, 2005, and became a No. 1 bestseller on the Amazon Japan site. On August 8, 2011, Japanese actor Sousuke Takaoka openly showed his dislike for the Korean Wave on Twitter, which triggered an Internet movement to boycott Korean programs on Japanese television.[171] Anti-Korean sentiment also surfaced when Kim Tae-Hee, a Korean actress, was selected to be on a Japanese soap opera in 2011: since she had been an activist in the Liancourt Rocks dispute for the Dokdo movement in Korea, some Japanese people were enraged that she would be on the Japanese TV show. There was a protest against Kim Tae-Hee in Japan, which later turned into a protest against the Korean Wave. According to a Korea Times article posted in February 2014, "Experts and observers in Korea and Japan say while attendance at the rallies is still small and such extreme actions are far from entering the mainstream of Japanese politics, the hostile demonstrations have grown in size and frequency in recent months."[172]

The Korean entertainment industry has also been criticised for its methods and links to corruption, as reported by Al Jazeera in February 2012.[173]

In the West, some commentators noted similarities between the South Korean Ministry of Culture's support of the Korean Wave and the CIA's involvement in the Cultural Cold War with the former Soviet Union. According to The Quietus magazine, suspicion of Hallyu as a venture sponsored by the South Korean government to strengthen its political influence bears "a whiff of the old Victorian fear of Yellow Peril".[174]

The South Korean entertainment industry has been faced with claims of mistreatment towards its musical artists. This issue came to a head when popular boy group Dong Bang Shin Ki, better known as DBSK or TVXQ, brought their management company to court over allegations of mistreatment. The artist claimed they had not been paid what they were owed and that their 13-year long contracts were far too long. While the court did rule in their favor, allegations of mistreatment of artists is still rampant. [175]

See also

- Cinema of Korea

- Cool Britannia

- Cool Japan

- Taiwanese Wave

- Korean cuisine

- Culture of Korea

- Culture of South Korea

- Dynamic Korea

- Hallyuwood

- Korean animation

- Korean drama

- Korean rock

- K-pop

- Manhwa

- Miracle on the Han River

- Presidential Council on Nation Branding, Korea

- List of K-Pop concerts held outside Asia

- List of J-Pop concerts held outside Asia

References

- ↑ "Romanization of Korean". The National Institute of the Korean Language. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Farrar, Lara (December 31, 2010). "'Korean Wave' of pop culture sweeps across Asia". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ↑ Ravina, Mark (2009). "Introduction: Conceptualizing the Korean Wave". Southeast Review of Asian Studies.

- ↑ Kim, Ju Young (2007). "Rethinking media flow under globalisation: rising Korean wave and Korean TV and film policy since 1980s". University of Warwick Publications.

- ↑ Yoon, Lina. (2010-08-26) K-Pop Online: Korean Stars Go Global with Social Media. TIME. Retrieved on 2011-02-20.

- ↑ JAMES RUSSELL, MARK. "The Gangnam Phenom". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

First taking off in China and Southeast Asia in the late 1990s, but really spiking after 2002, Korean TV dramas and pop music have since moved to the Middle East and Eastern Europe, and now even parts of South America.

- ↑ "South Korea's K-pop spreads to Latin America". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Brown, August (29 April 2012). "K-pop enters American pop consciousness". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

The fan scene in America has been largely centered on major immigrant hubs like Los Angeles and New York, where Girls' Generation sold out Madison Square Garden with a crop of rising K-pop acts including BoA and Super Junior.

- ↑ "South Korea pushes its pop culture abroad". BBC. 2011-11-08. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ↑ South Korea’s soft power: Soap, sparkle and pop The Economist (August 9, 2014). Retrieved on August 12, 2014.

- 1 2 Melissa Leong (August 2, 2014). "How Korea became the world's coolest brand". Financial Post. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Kwak, Donnie. "PSY's 'Gangnam Style': The Billboard Cover Story". Billboard. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

The Korean music industry grossed nearly $3.4 billion in the first half of 2012, according to Billboard estimates, a 27.8% increase from the same period last year.

- ↑ "Hallyu: Confluence of politics, economics and culture". The Daily Tribune. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

Hallyu was derived from the two Korean words "Han" for "Korean" and "Ryu" for "wave," bringing about the present-day name for Korean Wave, a global phenomena about the popularity of Korean dramas.

- 1 2 Kim, J. (2014). Reading Asian Television Drama: Crossing Borders and Breaking Boundaries. London: IB Tauris.

- ↑ Parc, Jimmyn and Moon, Hwy-Chang (2013) “Korean Dramas and Films: Key Factors for Their International Competitiveness”, Asian Journal of Social Science 41(2): 126-149.

- ↑ Nye, Joseph. "South Korea's Growing Soft Power". Harvard University. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

Indeed, the late 1990s saw the rise of "Hallyu", or "the Korean Wave" — the growing popularity of all things Korean, from fashion and film to music and cuisine.

- ↑ "South Korea: The king, the clown and the quota". The Economist. 18 February 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "The Future, after the Screen Quota". The KNU Times. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Lee, Hyung-Sook (2006). Between Local and Global: The Hong Kong Film Syndrome in South Korea. ProQuest. p. 48.

- ↑ Choi, Jinhee (2010). The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Global Provocateurs. Wesleyan University Press. p. 16.

- ↑ What is the future of Korean film?, The Korea Herald

- ↑ ROUSSE-MARQUET, Jennifer. "K-pop : the story of the well-oiled industry of standardized catchy tunes". Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- 1 2 Shim, Doobo. "Waxing the Korean Wave" (PDF). National University of Singapore. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Huat, Chua Beng; Iwabuchi, Koichi (2008). East Asian pop culture. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University press. ISBN 9789622098923.

- ↑ Onishi, Norimitsu (29 June 2005). "South Korea adds culture to its export power". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

What is more, South Korea, which long banned cultural imports from Japan, its former colonial ruler, was preparing to lift restrictions starting in 1998. Seoul was worried about the onslaught of Japanese music, videos and dramas, already popular on the black market. So in 1998 the Culture Ministry, armed with a substantial budget increase, carried out its first five-year plan to build up the domestic industry. The ministry encouraged colleges to open culture industry departments, providing equipment and scholarships. The number of such departments has risen from almost zero to more than 300.

- ↑ MACINTYRE, DONALD (10 September 2001). "Korea's Big Moment". Time. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

Technical quality improved steadily and genres multiplied. Shiri, released in 1999, was the breakthrough. Hollywood-style in its pacing and punch, it probed the still-sensitive issue of relations between the two Koreas through the story of a North Korean assassin who falls in love with a South Korean counterintelligence agent. The film sold 5.8 million tickets, shattering the previous record for a locally made movie of 1 million. Its $11 million box office grabbed the attention of investors, who are clamoring for new projects.

- ↑ U.N. Panel Approves Protections for Foreign Films, NPR

- ↑ Ji-myung, Kim. "Serious turn for 'hallyu 3.0'". The Korea Times. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Kim, Hyung-eun. "Hallyu bridges gap, but rift with China remains" Check

|url=value (help). JoongAng Ilb. Retrieved 21 March 2013. - ↑ When the Korean wave ripples, International Institute for Asian Studies

- 1 2 "A little corner of Korea in India". BBC. 17 October 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ↑ Kember, Findlay. "Remote Indian state hooked on Korean pop culture". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ "List of million sellers in 2002" (in Japanese). RIAJ. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- ↑ Celdran, David. "It's Hip to Be Asian". PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Kee-yun, Tan. "Welcome back pretty boys". Asiaone. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Hewitt, Duncan (20 May 2002). "Taiwan 'boy band' rocks China". BBC. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Lee, Claire. "Remembering 'Winter Sonata,' the start of hallyu". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ Chua, Beng Huat; Iwabuchi, Koichi (2008-02-01). East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622098923.

- ↑ "The Korean Wave (Hallyu) in East Asia: A Comparison of Chinese, Japanese, and Taiwanese Audiences Who Watch Korean TV Dramas".

- ↑ "A Study of Japanese Consumers of the Korean Wave" (PDF).

- ↑ Han, Hee-Joo; Lee, Jae-Sub (2008-06-01). "A Study on the KBS TV Drama Winter Sonata and its Impact on Korea's Hallyu Tourism Development". Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 24 (2-3): 115–126. doi:10.1080/10548400802092593. ISSN 1054-8408.

- ↑ Hanaki, Toru; Singhal, Arvind; Han, Min Wha; Kim, Do Kyun; Chitnis, Ketan (2007-06-01). "Hanryu Sweeps East Asia How Winter Sonata is Gripping Japan". International Communication Gazette. 69 (3): 281–294. doi:10.1177/1748048507076581. ISSN 1748-0485.

- ↑ Lee, Claire. "Remembering 'Winter Sonata,' the start of hallyu". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

The show's popularity in Japan was surprising to many, including the producer Yoon Suk-ho and then-Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, who in 2004 famously said, "Bae Yong-joon is more popular than I am in Japan."

- ↑ Lee (이), Hang-soo (항수). "홍콩인들 "이영애·송혜교 가장 좋아"". Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ↑ Celdran, David. "It's Hip to Be Asian". PHILIPPINE CENTER FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Williamson, Lucy (26 April 2011). "South Korea's K-pop craze lures fans and makes profits". BBC. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ↑ Faiola, Anthony (31 August 2006). "Japanese Women Catch the 'Korean Wave'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

There's only one more thing this single Japanese woman says she needs to find eternal bliss – a Korean man. She may just have to take a number and get in line. In recent years, the wild success of male celebrities from South Korea – sensitive men but totally ripped – has redefined what Asian women want, from Bangkok to Beijing, from Taipei to Tokyo. Gone are the martial arts movie heroes and the stereotypical macho men of mainstream Asian television. Today, South Korea's trend-setting screen stars and singers dictate everything from what hair gels people use in Vietnam to what jeans are bought in China. Yet for thousands of smitten Japanese women like Yoshimura, collecting the odd poster or DVD is no longer enough. They've set their sights far higher – settling for nothing less than a real Seoulmate.

- ↑ "K-Drama: A New TV Genre with Global Appeal". Korean Culture and Information Service. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "K Wave in Sri Lanka". Wordpress. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- ↑ "Korea in Nepal". beed. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ "Korean fever strikes Bhutan". Inside ASEAN. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

- ↑ Brown, August (29 April 2012). "K-pop enters American pop consciousness". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Hampp, Andrew. "Secrets Behind K-Pop's Global Success Explored at SXSW Panel". Billboard. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

That's a long way from even a few years ago, when panel moderator Sang Cho, chief operating officer of Korean TV company Mnet, would start pitching music programming to U.S. executives. "We probably showed about 300 music videos to top producers and record labels. In the beginning there were relationships so they would be courteous, but it was not a serious conversation," he said. "It's a different dialogue now."

- ↑ Oh, Esther. "K-Pop taking over the world? Don't make me laugh". CNN. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

Like BoA, Se7en also tried to find success in North America and worked alongside Mark Shimmel, Rich Harrison and Darkchild. The result? Complete flops.

- ↑ James Russell, Mark. "The Gangnam Phenom". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ↑ Iranians hooked on Korean TV drama, Global Post

- ↑ Mee-yoo, Kwon. "Int'l fans visit Korea for Seoul Drama Awards". Korea Times. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

The hit Korean drama "Jumong" was broadcast in Romania earlier this year, attracting some 800,000 viewers to the small screen.

- 1 2 "Korea's mark on an expectation-defying Iran". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

The Korean wave, or hallyu, has also made significant forays into Iran. Korean period dramas, "Jumong" in particular, were smash hits. Jumong ― the founding monarch of Korea's ancient Goguryeo kingdom (37 B.C.-A.D. 668) ― has become the most popular TV drama representing Korea here, with its viewer ratings hovering around 80 to 90 percent.

- ↑ "'K-pop' goes global". CNN. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ "(LEAD)(Yonhap Interview) Peruvian vice president hopes for further economic ties". Yonhap. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

"K-pop and soap operas have taken popularity. It was one of the main factors that made Peruvian people wanting to get to know South Korea more," Espinoza said.

- ↑ FLOTUS (First Lady of the United States). "Last week, we picked Napa cabbage in the garden. Now, we're using it to make kimchi in the kitchen...". Twitter. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "South Korea Digests White House Kimchi Recipe". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Vilas-Boas, Eric. "Will the White House Kitchen Go Global in the Second Term?". Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ HAWKES, STEVE. "Psy-high demand for Korean grub". London: The Sun. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Hallyu erobert die Welt" (in German). Deutschlandradio. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Le 20h avant l'heure : le phénomène K Pop déferle en France" (in French). TF1. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Myanmar's Suu Kyi urges 'more human' democracy". AFP. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

On Thursday night she had a special dinner with a host of South Korean soap opera stars, one of whom she had personally invited because of his resemblance to her assassinated father. Ahn Jae-Wook, a popular singer and actor, starred in the 1997 TV drama "Star in My Heart," which was a big hit in Myanmar.

- ↑ "Full text of Park's inauguration speech". Yonhap. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

The new administration will elevate the sanctity of our spiritual ethos so that they can permeate every facet of society and in so doing, enable all of our citizens to enjoy life enriched by culture. We will harness the innate value of culture in order to heal social conflicts and bridging cultural divides separating different regions, generations, and social strata. We will build a nation that becomes happier through culture, where culture becomes a fabric of daily life, and a welfare system that embodies cultural values. Creative activities across wide-ranging genres will be supported, while the contents industry which merges culture with advanced technology will be nurtured. In so doing, we will ignite the engine of a creative economy and create new jobs. Together with the Korean people we will foster a new cultural renaissance or a culture that transcends ethnicity and languages, overcomes ideologies and customs, contributes to the peaceful development of humanity, and is connected by the ability to share happiness.

- ↑ "Park to put policy priority on culture". The Korea Times. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Tourism To South Korea Number of tourists visiting South Korea expected to top 10 million - ...". eturbonews.com.

- ↑ "Culture to be groomed as next growth engine". The Korea Times. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

As a recent state survey indicates, there are many who believe that the popularity of hallyu faces an uncertain future. Around 66 percent of 3,600 respondents in nine countries (China, Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, U.S., Brazil, France, U.K. and Russia) said that the popularity of Korean culture will subside in the next four years

- ↑ "KOTRA '작년 한류 문화콘텐츠 수출효과 3조2000억원'". view.asiae.co.kr. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ Mukasa, Edwina (15 December 2011). "Bored by Cowell pop? Try K-pop". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

The result, according to a survey conducted by the Korean Culture and Information Service, is that there are an estimated 460,000 Korean-wave fans across Europe, concentrated in Britain and France, with 182 hallyu fan clubs worldwide boasting a total of 3.3m members.

- ↑ "K-pop drives hallyu craze: survey". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

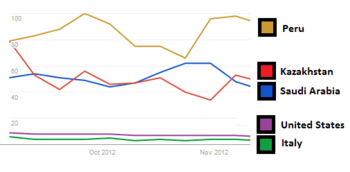

- ↑ "Web Search Interest: "super junior". Saudi Arabia, Kazakhstan, Peru, Italy, United States, Sep–Dec 2012.". Google Trends. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ "Source : Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (South Korea)". KOREA.net. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

Meanwhile, the number of members of the Hallyu fan clubs has exceeded the 1,000 mark. Amid such trends, TV broadcasters are airing an increasing number of the Korean soap operas.

- 1 2 3 4 "Middle East: Korean pop 'brings hope for peace'". BBC. 2013-08-07. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- 1 2 Shin, Hyon-hee. "K-pop craze boosts Korea's public diplomacy". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

In Chile alone, there are about 20,000 members of 200 clubs also for Big Bang, 2PM, CN Blue, SHINee, MBLAQ and other artists. Peru is another K-pop stronghold, with nearly 8,000 people participating in 60 groups.

- ↑ "K-pop magazine published in Russia". Korea.net. Oct 15, 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ↑ DAMIEN CAVE (21 September 2013). "For Migrants, New Land of Opportunity Is Mexico". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

there are now 70 fan clubs for Korean pop music in Mexico, with at least 60,000 members.

- ↑ Falletti, Sébastien. "La vague coréenne déferle sur le Zénith" (in French). Le Figaro. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

"C'est un mélange de sons familiers, avec en plus une touche exotique qui fait la différence," explique Maxime Pacquet, fan de 31 ans. Cet ingénieur informatique est le président de l'Association Korea Connection qui estime à déjà 100.000 le nombre d'amateurs en France.

- ↑ "K-POP İstanbul'u sallayacak!" (in Turkish). Milliyet. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

Türkiye’de kayıtlı 150.000 K-POP fanı bulunuyor.

- ↑ "Overseas 'hallyu' fan clubs estimated to have 3.3 million members". Yonhap. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ "Riding the 'Korean Wave'". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

The cultural wave, or hallyu, is establishing itself as a global phenomenon that has already washed over East Asia and is now reaching the shores of Europe, Latin America and the Middle East. As a result, there are now more than 830 hallyu fan clubs in more than 80 countries, with a total of 6 million members.

- ↑ Park Jin-hai (2014-01-08). "`Hallyu' fans swell to 10 mil.". The Korea Times. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ "Foreign Ministry to Host a K-Pop Show as Part of Hallyu Diplomacy". Foreign Ministry (South Korea). Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "South Korea-China Mutual Perceptions: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly" (PDF). U.S.-Korea Institute at SAIS. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "Korea swallows its pride in Chinese kimchi war". Asia Times Online. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

. Chinese President Hu Jintao was reported to be a fan of the Korean historical soap opera Dae Jang Geum, which was watched by more than 180 million Chinese when it was broadcast last September.

- ↑ 温家宝总理接受韩国新闻媒体联合采访 (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

对于"韩流"这种文化现象,中国人民特别是年轻人都很喜欢,中国政府会继续鼓励包括"韩流"在内的两国文化交流活动。

- ↑ 2013-07-23, South Korean Soap Operas: Just Lowbrow Fun? , Korea Real Time, The Wall Street Journal

- ↑ 2014-03-20, Chinese Fans of Korean Soap Operas: Don’t Call Us Dumb, Korea Real Time, The Wall Street Journal

- 1 2 Frater, Patrick (2016-08-04). "China Reportedly Bans Korean TV Content, Talent". Variety. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ Fu, Eva (2016-08-08). "K-Pop Stars Become Scapegoats in China's Protests Against Anti-Missile Deployment". Epoch Times. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ Brzeski, Patrick (2016-08-02). "China Takes Aim at K-pop Stars Amid Korean Missile-Defense Dispute". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2016-09-05.

- ↑ "DIPLOMATIC BLUEBOOK 2005" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan). Retrieved 11 May 2013.

Mutual interest and exchange between the peoples of Japan and the ROK expanded substantially during 2004, spurred by the joint hosting of the 2002 FIFA World Cup, the holding of the Year of Japan-ROK National Ex- change 14 and the Japan-ROK Joint Project for the Fu- ture, 15 and the Hanryu (Korean style) boom in Korean popular culture in Japan.

- ↑ "Japanese housewives are crazy about Korean stars". Global Times. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

It seems nothing can be done really to stem the new Korean Wave, with high-profile fans in Japan including current first lady Miyuki Hatoyama and previous first lady Akie Abe.

- 1 2 Cho, Hae-joang (2005). "Reading the "Korean Wave" as a Sign of Global Shift". Korea Journal.

- ↑ "Anti-Korean Wave in Japan turns political". CNN. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Kim, J. (2014). Reading Asian television drama: Crossing borders and breaking boundaries. London: IB Tauris.

- ↑ "The 'Asian Wave' hits Saudi Arabia". Saudi Gazette. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

Egypt and Iran has been the center of the "hallyu" phenomena in the Middle East for a few years now. While Egypt went crazy after the dramas "Autumn in my Heart" and "Winter Sonata," Iran went gaga when its state television aired "Emperor of the Sea" and "Jewel in the Palace".

- ↑ "K--Pop Concerts Head To New Countries As Hallyu Expands". KpopStarz.

- ↑ ONISHI, NORIMITSU (28 June 2005). "Roll Over, Godzilla: Korea Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

South Korea has also begun wielding the non-economic side of its new soft power. The official Korean Overseas Information Service last year gave "Winter Sonata" to Egyptian television, paying for the Arabic subtitles. The goal was to generate positive feelings in the Arab world toward the 3,200 South Korean soldiers stationed in northern Iraq.

- ↑ "Israeli fans latch on to ever-mobile K-pop wave". Music Asia. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Lyan, Irina. "Hallyu across the Desert: K-pop Fandom in Israel and Palestine". Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ Nissim Otmazgin, Irina Lyan (December 2013). "Hallyu across the Desert: K-pop Fandom in Israel and Palestine" (PDF). Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ↑ "Korean Wave To Hit Hebrew University On May 7". CFHU. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "'Autumn in My Heart' Syndrome in Egypt". Korean Broadcasting System. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "'Autumn in My Heart' Syndrome in Egypt". Korean Broadcasting System. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

"This drama proved extremely effective in enhancing Korea 's international image, which has been undermined by the troop deployment in Iraq ,' added Lee.

- 1 2 "Song Il Gook is a superstar in Iran because of Jumong". Allkpop. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "Book probes transnational identity of 'hallyu'". The Korea Times. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

Korean television dramas reinforce traditional values of Confucianism that Iranians find more closely aligned to Islamic culture, implying that cultural proximity contributes to the Islamic Korean wave. "Reflecting traditional family values, Korean culture is deemed 'a filter for Western values' in Iran," the article says.

- ↑ "Foreign broadcasts, DVDs challenge Iran grip on TV". Reuters. 19 January 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- 1 2 IRIB director visits location of South Korean TV series popular in Iran, The Tehran Times

- ↑ "IRIB director meets South Korean media officials". IRIB World Service. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "Scholars illuminates Silla-Persian royal wedding". The Korea Times. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "Musical 'Daejanggeum' to premiere in the palace". Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

In Iran, the drama recorded 86 percent TV ratings.

- 1 2 3 Korean Culture and Information Service (KOCIS). "Korean wave finds welcome in Iraq". korea.net.

- ↑ <李대통령 "터키인, 한국기업 취업 길 많다"> (in Korean). Yonhap. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ 김재중, 터키 국빈 만찬 참여..한류스타 위상 (in Korean). Nate. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "'Australia and Korea: Partners and Friends', Speech to Yonsei University, Seoul". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Australia). Retrieved 10 May 2013.

Australia has even caught the "Korean wave", the renaissance of your popular culture reaching all the way to our shores. We welcomed some of Korea's biggest reality television programs to our country last year – and tens of thousands of young Koreans and Australians watched your best known singing stars perform at a K-Pop concert in Sydney last year. Our friendship is strong and growing and when I return to Australia, I will do so enlivened and inspired by your Korean example.

- ↑ "NZ Asia Institute Conference celebrates the New Zealand – Korea "Year of Friendship" 16–17 November 2012". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (New Zealand). Retrieved 10 May 2013.

Korean food and music, both traditional and modern, are becoming well known in New Zealand. Indeed there is now a 4,000 strong association of K-Pop followers in New Zealand. So the 'Korean Wave' is now becoming part of the Kiwi lifestyle.

- 1 2 "Hallyu in Rumänien – ein Phänomen aus Südkorea" (in German). Allgemeine Deutsche Zeitung für Rumänien. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "ROUMANIE • Mon feuilleton coréen, bien mieux qu'une telenovela" (in French). Courrier International. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ "La France et la République de Corée" (in French). Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (France). Retrieved 10 May 2013.

La culture populaire coréenne connaît un succès grandissant à travers le monde. Ce phénomène porte le nom de " Hallyu ", ou " vague coréenne ".

- ↑ "Auswärtiges Amt — Kultur und Bildungspolitik" (in German). Auswärtiges Amt. Retrieved 2013-05-10.

Koreanische Pop- und Unterhaltungskultur ("Hallyu", Telenovelas, K-Popbands etc.), verzeichnen in Asien und darüber hinaus große Publikumserfolge.

- ↑ Hugo Swire. "Anglo-Korean Society Dinner — Speeches". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

. As "Gangnam Style" has demonstrated, your music is global too.

- ↑ "Remarks by President Obama at Hankuk University". White House. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

It's no wonder so many people around the world have caught the Korean Wave, Hallyu.

- ↑ "Remarks by President Obama and President Park of South Korea in a Joint Press Conference". White House. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

And of course, around the world, people are being swept up by Korean culture – the Korean Wave. And as I mentioned to President Park, my daughters have taught me a pretty good Gangnam Style.

- ↑ "Video Recording for the Republic of Korea's Independence Day". United States Department of State. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

And people in every corner of the world can see it, as the "Korean Wave" spreads Korean culture to countries near and far.

- ↑ "Seoul, Republic of Korea, 30 October 2012 – Secretary-General's address to the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea: "The United Nations and Korea: Together, Building the Future We Want" [as prepared for delivery]". United Nations. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

...the Hallyu-wave and Korean pop music, Korean culture is making its mark on the world.

- ↑ 金健人主编 (2008). 《"韩流"冲击波现象考察与文化研究》. 北京市:国际文化出版公司. p. 4. ISBN 7801737792.

- ↑ Liu, H. (Yang). (2014, Summer). The Latest Korean TV Format Wave on Chinese Television: A Political Economy Analysis. Simon Fraser University.

- ↑ Faiola, Anthony (August 31, 2006). "Japanese Women Catch the 'Korean Wave'". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ↑ "중국판 런닝맨 '달려라형제(奔跑吧, 兄弟!)' 중국서 인기 폭발! | DuDuChina". DuDu China. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- ↑ "Popular China TV show Running Man to be filmed in Australia - News & Media - Tourism Australia". www.tourism.australia.com. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- ↑ Shim Doobo. (2006). ‘Hybridity and Rise of Korean Popular Culture in Asia.’ Media, Culture & society. 28 (1), pp. 25-44.

- ↑ "2012 BBC Country Ratings" (PDF). Globescan/BBC World Service. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ↑ Oliver, Christian. "South Korea's K-pop takes off in the west". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ South Korea’s pop-cultural exports, The Economist

- ↑ South Korea’s K-pop takes off in the west, Financial Times

- 1 2 Korean Cultural Exports Still Booming, The Chosun Ilbo

- ↑ "Hallyu seeks sustainability". The Korea Herald. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

According to the Hallyu Future Strategy Forum's 2012 report, hallyu was worth 5.6 trillion won in economic value and 95 trillion won in asset value.

- 1 2 2012년 1분기 콘텐츠산업 동향분석보고서 (애니메이션/케릭터산업편) [Contents Industry Trend Analysis Report (Animation/Character Industries) 1st quarter, 2012] (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Creative Contents Agency. July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ 2012년 1분기 콘텐츠산업 동향분석보고서 (방송(방송영상독립제작사포함)산업편) [Contents Industry Trend Analysis Report (Broadcasting(Including independent broadcasting video producers) Industry) 1st quarter, 2012] (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Creative Contents Agency. July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- 1 2 2012년 1분기 콘텐츠산업 동향분석보고서 (출판/만화산업편) [Contents Industry Trend Analysis Report (Publishing/Cartoon Industries) 1st quarter, 2012] (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Creative Contents Agency. July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ 2012년 1분기 콘텐츠산업 동향분석보고서 (게임산업편) [Contents Industry Trend Analysis Report (Gaming Industry) 1st quarter, 2012] (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Creative Contents Agency. July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ 2012년 1분기 콘텐츠산업 동향분석보고서 (지식정보산업편) [Contents Industry Trend Analysis Report (Knowledge/Information Industry) 1st quarter, 2012] (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Creative Contents Agency. July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ 2012년 1분기 콘텐츠산업 동향분석보고서 (영화산업편) [Contents Industry Trend Analysis Report (Movie Industry) 1st quarter, 2012] (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Creative Contents Agency. July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ↑ 2012년 1분기 콘텐츠산업 동향분석보고서 (음악산업편) [Contents Industry Trend Analysis Report (Music Industry) 1st quarter, 2012] (PDF) (in Korean). Korea Creative Contents Agency. July 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- 1 2 ""Korean Wave" set to swamp North Korea, academics say". Reuters. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "North Korea cracks down on 'Korean wave' of illicit TV". UNHCR. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

In May 2007, Hwangjini became the first South Korean movie ever to be publicly previewed in North Korea. The main character, an artistic and learned woman of great beauty known as a kisaeng, is played by Song Hye Gyo, one of the most popular Korean Wave stars of the moment. The story is based on a novel by North Korean author Hong Seok Jung, and it was previewed at Mount Kumgang in North Korea.

- ↑ "North Korea cracks down on 'Korean wave' of illicit TV". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ Hwang Chang Hyun. "Winds of Unification Still Blowing...". Daily NK. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Diffusion de la vague coréenne "hallyu" au Nord par TV portable". Yonhap (in French). October 22, 2013.

- ↑ SULLIVAN, TIM. "North Korea cracks down on knowledge smugglers". Associated Press. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ "North Korea cracks down on knowledge smugglers". Associated Press. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

There has definitely been a push to roll back the tide of the flow of information," said Nat Kretchun, associate director of an international consulting group InterMedia, which released a report earlier this year about information flow into North Korea, based on surveys of hundreds of recent North Korean defectors. The study was commissioned by the U.S. State Department. His conclusion: North Korea is increasingly anxious to keep information at bay, but has less ability to control it. People are more willing to watch foreign movies and television programs, talk on illegal mobile phones and tell family and friends about what they are doing, he said. "There is substantial demand" for things like South Korean movies and television programs, said Kretchun. "And there are intensely entrepreneurial smugglers who are more than willing to fulfill that demand.

- ↑ "North Korea: Stop Crackdown on Economic 'Crimes'". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

One North Korean woman told Human Rights Watch that, "My happiest moments when I was in North Korea were watching [South] Korean TV shows. I felt like I was living in that same world [as those actors on the show].... Watching Korean shows was really common in North Korea."

- ↑ "Latest S. Korean pop culture penetrates N. Korea". Yonhap. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "North Korea: Stop Crackdown on Economic 'Crimes'". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

Entertainment shows from South Korea are particularly popular and have served to undermine the North Korean government's negative portrayals of South Korea.

- ↑ "Korea, Monthly Statistics of Tourism(1975~1996) | key facts on toursim | Tourism Statistics". kto.visitkorea.or.kr. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ↑ "Korea, Monthly Statistics of Tourism - key facts on toursim - Tourism Statistics". visitkorea.or.kr.

- 1 2 Hee- Joo Han, Jae-Sub Lee (2008) A study on the KBS TV drama Winter Sonata and its inpact on Korea’s Hallyu tourism development. Journal of Travel and Marketing 24: 2-3, 115-126

- ↑ "KTO launches 'Imagine your Korea' -ETB Travel News Asia". etbtravelnews.com.

- ↑ "KTO Launches Imagine Your Korea Campaign". superadrianme.com.

- 1 2 "Harnessing K-Pop for tourism | CNN Travel". travel.cnn.com. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ Seongseop (Sam) Kim , Sangkyun (Sean) Kim , Cindy (Yoonjoung) Heo,. (2014) Assessment of TV Drama/Film Production Towns as a Rural Tourism Growth Engine. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research.

- ↑ Howard, K. (2010). Chua Beng Huat and Koichi Iwabuchi (eds): East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. (TransAsia: Screen Cultures.) xi, 307 pp. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008. ISBN 978 962 209 893 0. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 73(01), p.144

- ↑ "Kim Soo-hyun elected tourism ambassador". Yahoo News Singapore. 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Korean Wave backlash in Taiwan : The DONG-A ILBO". english.donga.com. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ Nam, Soo-hyoun; Lee, Soo-jeong (February 17, 2011). "Anti-Korean Wave backlash has political, historical causes". Korea JoongAng Daily. JoongAng Ilbo. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- ↑ Maliangkay, Roald (2006). ‘When the Korean Wave Ripples.’ IIAS Newsletter, 42, p. 15.

- ↑ thunderstix (31 July 2011). "Talk of the Town: Anti-Korean Wave?". Soompi. Soompi Inc. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ "Anti-hallyu voices growing in Japan". koreatimes. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ 101 East (1 February 2012). "South Korea's Pop Wave". Aljazeera. Aljazeera. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Barry, Robert. "Gangnam Style & How The World Woke Up to the Genius of K-Pop". The Quietus. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

While suspicious talk of Hallyu as 'soft power' akin to the CIA's cultural Cold War bears a whiff of the old Victorian fear of yellow peril,

- ↑ Williamson, Lucy. (15 June 2011).“The dark side of South Korean pop music.” BBC News. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Korean Wave. |

| Look up korean wave in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Critical article by Roald Maliangkay on the recent development of the Wave

- "'Korean Wave' Piracy Hits Music Industry", BBC, November 9, 2001.

- "A rising Korean wave: If Seoul sells it, China craves it", The International Herald Tribune, January 10, 2006.

- Korean Culture & Content Agency

- Shim Doo Bo, Hybridity and the rise of Korean pop culture in Asia, Media, Culture and Society, January 2006, Vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 25–44.