Kopis

The term kopis (from Greek κοπίς, plural kopides[1] from κόπτω - koptō, "to cut, to strike";[2] alternatively a derivation from the Ancient Egyptian term khopesh for a cutting sword has been postulated[3]) in Ancient Greece could describe a heavy knife with a forward-curving blade, primarily used as a tool for cutting meat, for ritual slaughter and animal sacrifice, or refer to a single edged cutting or "cut and thrust" sword with a similarly shaped blade.

Characteristics

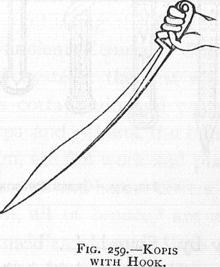

The kopis sword was a one-handed weapon. Early examples had a blade length of up to 65 cm, making it almost equal in size to the spatha. Later Macedonian examples tended to be shorter with a blade length of about 48 cm. The kopis had a single-edged blade that pitched forward towards the point, the edge being concave on the part of the sword nearest the hilt, but swelling to convexity towards the tip. This shape, often termed "recurved", distributes the weight in such a way that the kopis was capable of delivering a blow with the momentum of an axe, whilst maintaining the long cutting edge of a sword and some facility to execute a thrust. Some scholars have claimed an Etruscan origin for the sword, as such swords have been found as early as the 7th century BC in Etruria.[4]

The kopis is often compared to the contemporary Iberian falcata and the more recent, and shorter, Nepalese kukri. The word itself is a Greek feminine singular noun. The difference in meaning between kopis and makhaira (μάχαιρα, another Greek word, meaning "chopper" or "short sword", "dagger") is not entirely clear in ancient texts,[5] but modern specialists tend to discriminate between single-edged cutting swords, those with a forward curve being classed as kopides, those without as makhairai.[6]

Use

The Ancient Greeks often used single-edged blades in warfare, as attested to by art and literature; however, the double-edged, straight, and more martially versatile xiphos is more widely represented. Greek heavy infantry hoplites favored straight swords, but the downward curve of the kopis made it especially suited to mounted warfare. The general and writer Xenophon recommended the single edged kopis sword (which he did not distinguish from the makhaira) for cavalry use in his work On Horsemanship; saying, "I recommend a kopis rather than a xiphos, because from the height of a horse’s back the cut of a machaira will serve you better than the thrust of a xiphos".[7] The precise wording of Xenophon's description suggests the possibility that the kopis was regarded as a specific variant within a more general class, with the term makhaira denoting any single-edged cutting sword.

Greek art shows Persian soldiers wielding the kopis or an axe rather than the straight-bladed Persian akinakes.

It has been suggested that the yatagan, used in the Balkans and Anatolia during the Ottoman Period, was a direct descendant of the kopis.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ κοπίς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ κόπτω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ Gordon, D.H. (1958) "Scimitars, Sabres and Falchions". in Man, Vol 58, p. 24

- ↑ Connolly, P. (1981) Greece and Rome at War. Macdonald Phoebus, London, pp. 63 and 99.

- ↑ For a good summary of the evidence, see F. Quesada Sanz: "Máchaira, kopís, falcata" in Homenaje a Francisco Torrent, Madrid, 1994, pp. 75–94.

- ↑ Tarassuk & Blair, s.v. "kopis", The Complete Encyclopedia of Arms and Weapons, 1979.

- ↑ Sidnell, P. (2006) Warhorse: Cavalry in Ancient Warfare. Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Gordon, D.H. (1958) "Scimitars, Sabres and Falchions". in Man, Vol 58, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, pp. 25–26.