Klaus Barbie

| Klaus Barbie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Nikolaus Barbie |

| Born |

25 October 1913 Bad Godesberg, Germany |

| Died |

23 September 1991 (aged 77) Lyon, France (incarcerated) |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1933–1945 |

| Rank |

|

| Service number | |

| Unit | Sicherheitsdienst |

| Battles/wars | Ñancahuazú Guerrilla |

| Awards | Iron Cross First Class[2] |

Nikolaus "Klaus" Barbie (25 October 1913 – 23 September 1991) was an SS-Hauptsturmführer (rank equivalent to army captain) and Gestapo member. He was known as the "Butcher of Lyon" for having personally tortured French prisoners of the Gestapo while stationed in Lyon, France. After the war, United States intelligence services employed him for their anti-Marxist efforts, and also helped him escape to South America. The Bundesnachrichtendienst (the West German intelligence agency) recruited him, and he may have helped the CIA capture Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara in 1967. Barbie is suspected of having had a hand in the Bolivian coup d'état orchestrated by Luis García Meza Tejada in 1980. After the fall of the dictatorship, Barbie no longer had the protection of the Bolivian government, and in 1983 was extradited to France, where he was convicted of crimes against humanity. He died of cancer in prison on 23 September 1991.

Early life and education

Nikolaus "Klaus" Barbie was born on 25 October 1913 in Godesberg, later renamed Bad Godesberg, which is today part of Bonn. The Barbie family came from Merzig, in the Saar near the French border. His patrilineal ancestors were likely French Roman Catholics named Barbier who had left France at the time of the French Revolution. In 1914, his father, also named Nickolaus, was conscripted to fight in the First World War. He returned an angry, bitter man. Wounded in the neck at Verdun and captured by the French, whom he hated, he never recovered his health. He became an alcoholic who abused his children. Until 1923, when he was 10, Klaus Barbie attended the local school where his father taught. Afterward, he attended a boarding school in Trier, and was relieved to be away from his abusive father. In 1925, the entire Barbie family moved to Trier.[2]

In June 1933, Barbie's younger brother, Kurt, died at the age of eighteen of chronic illness. Later that year, their father died. The death of his father derailed plans for the 20-year-old Barbie to study theology, or otherwise become an academic, as his peers had expected. While unemployed, Barbie was conscripted into the Nazi labour service, the Reichsarbeitsdienst. On 26 September 1935, aged 22, he joined the SS (member 272,284), and began working in the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the SS security service, which acted as the intelligence-gathering arm of the Nazi Party. On 1 May 1937, he became member 4,583,085 of the Nazi Party. In April 1939, Barbie became engaged to Regina Margaretta Willms, the 23-year-old daughter of a postal clerk.[2]

Second World War

After the German conquest and occupation of the Netherlands, Barbie was assigned to Amsterdam. In 1942 he was sent to Dijon, France, in the Occupied Zone. In November of the same year, at the age of 29, he was assigned to Lyon as the head of the local Gestapo. He established his headquarters at the Hôtel Terminus in Lyon, where he personally tortured prisoners, men, women and children alike,[3][4][5]—breaking extremities, using electroshock and sexually abusing them (including with dogs), among other methods. He became known as the "Butcher of Lyon".[6] In Marcel Ophüls's Oscar-winning documentary film, Hôtel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie, the daughter of a French Resistance leader based in Lyon recounts her father's torture by Barbie: her father was beaten and skinned alive, and his head was immersed in a bucket of ammonia; he died shortly afterward.[4]

Historians estimate that Barbie was directly responsible for the deaths of up to 14,000 people.[7][8] He arrested Jean Moulin, one of the highest-ranking members of the French Resistance and his most prominent captive. In 1943, he was awarded the "Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Swords" for his campaign against the French Resistance and the capture of Moulin, by Adolf Hitler.[9]

In April 1944, Barbie ordered the deportation to Auschwitz of a group of 44 Jewish children from an orphanage at Izieu.[10] After his reign of terror in Lyon he rejoined the SiPo-SD of Lyon in Bruyères, where he led an anti-partisan attack in Rehaupal in September 1944[11]

US intelligence and Bolivia

In 1947, Barbie was recruited as an agent for the 66th Detachment of the U.S. Army Counterintelligence Corps (CIC).[12] The U.S. used Barbie and other Nazi Party members to further anti-Communist efforts in Europe. Specifically, they were interested in British interrogation techniques which Barbie had experienced firsthand, and the identities of SS officers the British were using for their own ends. Later, the CIC housed him in a hotel in Memmingen, and he reported on French intelligence activities in the French zone of occupied Germany because they felt the French were infiltrated with Communists.[13]

The French discovered that Barbie was in U.S. hands and, having sentenced him to death in absentia for war crimes, made a plea to John J. McCloy, U.S. High Commissioner for Germany, to hand him over for execution, but McCloy allegedly refused.[13] Instead, the CIC allegedly helped him flee to Bolivia assisted by "ratlines" organized by U.S. intelligence services,[14] and by Croatian Roman Catholic clergy, including Father Krunoslav Draganović. The CIC asserted that Barbie knew too much about the network of German spies the CIC had planted in various European Communist organizations, and were suspicious of Communist influence within the French government, but their protection of Barbie may have been as much to avoid the embarrassment of having recruited him in the first place.[12]

In 1965, Barbie was recruited by the West German foreign intelligence agency Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), under the codename "Adler" (Eagle) and the registration number V-43118. His initial monthly salary of 500 Deutsche Mark was transferred in May 1966 to an account of the Chartered Bank of London in San Francisco. During his time with the BND, Barbie made at least 35 reports to the BND headquarters in Pullach.[15]

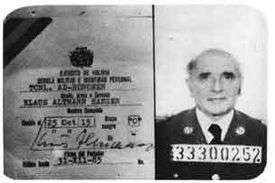

Barbie emigrated to Bolivia, where he lived well under the alias Klaus Altmann. It was easier and less embarrassing for him to find employment there than in Europe, and he enjoyed excellent relations with high-ranking Bolivian officials, including Bolivian dictators Hugo Banzer and Luis García Meza Tejada. "Altmann" was known for his German nationalist and anti-communist stances.[16] While engaged in arms-trade operations in Bolivia, he was appointed to the rank of lieutenant colonel within the Bolivian Armed Forces.[17]

Extradition, trial and death

Barbie was identified as living in Bolivia in 1971 by the Klarsfelds (Nazi hunters from France). The testimony of the Italian insurgent Stefano delle Chiaie before the Italian Parliamentary Commission on Terrorism suggests that Barbie took part in the "cocaine coup" of Luis García Meza Tejada, when the regime forced its way to power in Bolivia in 1980.[18] On 19 January 1983, the newly elected government of Hernán Siles Zuazo arrested Barbie and extradited him to France to stand trial.[19]

In 1984, Barbie was indicted for crimes committed as Gestapo chief in Lyon between 1942 and 1944. The jury trial started on 11 May 1987, in Lyon, before the Rhône Cour d'Assises. Unusually, the court allowed the trial to be filmed because of its historical value. A special courtroom with seating for an audience of about 700 was constructed.[20] The head prosecutor was Pierre Truche.

At the trial, Barbie was supported by Swiss financier François Genoud and defended by attorney Jacques Vergès. He was tried on 41 separate counts of crimes against humanity, based on the depositions of 730 Jews and French Resistance survivors, who described how he tortured and murdered prisoners.[21]

The father of then-French Minister for Justice Robert Badinter had died in Sobibor after being deported from Lyon during Barbie's tenure.[22]

Barbie gave his name as Klaus Altmann (the name he used while in Bolivia). Claiming his extradition was technically illegal, he asked to be excused from the trial and returned to his cell at Prison Saint-Paul. This was granted. He was brought back to court on 26 May 1987 to face some of his accusers, about whose testimony he had "nothing to say".

Barbie's defense attorney, Vergès, had a reputation for attacking the French political system, particularly in the historic French colonial empire. His strategy was to use the trial to talk about war crimes committed by France since 1945. This had less to do with the trial than with Verges' desire to undermine the French Fifth Republic. He got the prosecution to drop some of the charges against Barbie due to French legislation that had protected French citizens accused of the same crimes under the Vichy regime and in French Algeria. Vergès tried to argue that Barbie's actions were no worse than the supposedly ordinary actions of colonialists worldwide, and that his trial was tantamount to selective prosecution. During his trial, Barbie said, "When I stand before the throne of God, I shall be judged innocent."[23]

The court rejected the defense's argument. On 4 July 1987, Barbie was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. He died in prison in Lyon of leukemia, and cancer of the spine and prostate, four years later, at the age of 77.[24]

See also

- Operation Condor

- Operation Bloodstone

- Glossary of Nazi Germany

- French Resistance

- List of Nazi Party leaders and officials

- List of SS personnel

References

- ↑ Profile, holocaustresearchproject.org; accessed 29 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Profile, jewishvirtuallibrary.org; accessed 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Bönisch, Georg; Wiegrefe, Klaus (20 January 2011). "From Nazi to criminal to post-war spy: German intelligence hired Klaus Barbie as agent". Der Spiegel.

- 1 2 Hôtel Terminus (Motion picture). 1988.

- ↑ "Klaus Barbie: women testify of torture at his hands", upenn.edu; 23 March 1987.

- ↑ "Ich bin gekommen, um zu töten". Der Spiegel. 2 July 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ "Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie gets life". BBC. 3 July 1987. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ↑ "Klaus Barbie ausgeliefert". Der Spiegel. 4 February 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ "On behalf of his cruel crimes and specially for the Moulin case, Barbie was awarded, by Hitler himself, the First Class Iron Cross with Swords", jewishvirtuallibrary.org; accessed 29 September 2015.

- ↑ On the deportation of the children of Izieu, at Yad Vashem website

- ↑ "KLAUS BARBIE-THE BUTCHER OF LYON", dirkdeklein.net; accessed October 2016.

- 1 2 Wolfe, Robert (19 September 2001). "Analysis of the Investigative Records Repository file of Klaus Barbie". Interagency Working Group. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- 1 2 Cockburn, Alexander; Clair, Jeffrey St. (1998). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. Verso. pp. 167–70. ISBN 9781859841396. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ↑ Terkel, Studs (1985). The Good War. Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-32568-0.

- ↑ "Vom Nazi-Verbrecher zum BND-Agenten". Der Spiegel (in German). 19 January 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Hammerschmidt, Peter: "Die Tatsache allein, daß V-43 118 SS-Hauptsturmführer war, schließt nicht aus, ihn als Quelle zu verwenden". Der Bundesnachrichtendienst und sein Agent Klaus Barbie, Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft (ZfG), 59. Jahrgang, 4/2011. METROPOL Verlag. Berlin 2011, S. 333–349. (German)

- ↑ "He was even given the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Bolivian armed forces..", guardian.co.uk; accessed 1 September 2015.

- ↑ Laetitia Grevers (4 November 2012). "The Butcher of Bolivia". Bolivian Express Magazine. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Klaus Barbie, The Butcher of Lyon". Holocaust Research Project. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ L'avocat de la terreur [Terror's Advocate]. France: La Sofica Uni Etoile 3. 2007.

- ↑ Finkielkraut, Alain (1992). Remembering in Vain: The Klaus Barbie Trial and Crimes Against Humanity. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07464-3. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ↑ Beigbeder, Yves (2006). Judging War Crimes And Torture: French Justice And International Criminal Tribunals And Commissions (1940-2005). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 204–. ISBN 978-90-04-15329-5. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ↑ "Klaus Barbie profile". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ↑ Saxon, Wolfgang (26 September 1991). "Klaus Barbie, 77, Lyons Gestapo Chief". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Bower, Tom (1984). Klaus Barbie, the Butcher of Lyons. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-53359-9.

- Goni, Uki (2002). The Real Odessa: How Peron Brought the Nazi War Criminals to Argentina. Granta Books. ISBN 978-1-86207-403-3. A chapter in this book also follows how top Nazis made their way to Argentina and Latin America.

- Hammerschmidt, Peter: "Die Tatsache allein, daß V-43 118 SS-Hauptsturmführer war, schließt nicht aus, ihn als Quelle zu verwenden". Der Bundesnachrichtendienst und sein Agent Klaus Barbie, in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft (ZfG), 59. Jahrgang, 4/2011. METROPOL Verlag. Berlin 2011, S. 333–349.

- Hilberg, Raul (1982). "Barbie (SS, Lyon)". Die Vernichtung der europäischen Juden (in German) (110 ed.). Olle & Wolter. p. 453. ISBN 978-3-88395-431-8. OCLC 10125090. Case No. 77, Fn 908 KsD Lyon IV-B (gez. Ostubaf. Barbie) an BdS, Paris IV-B, 6 April 1944, RF-1235.

- Linklater, Magnus; Hilton, Isabel; Ascherson, Neal (1984). The Nazi Legacy: Klaus Barbie and the International Fascist Connection. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0-03-069303-9.

- Ryan Jr., Allan A. (2 August 1983). "Klaus Barbie and the United States Government: A Report to the Attorney General" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

External links

- French Judicial Archives on Klaus Barbie (French)

- Klaus Barbie at the German National Library (German)

- Klaus Barbie at the Internet Movie Database

- Klaus Barbie (Character) at the Internet Movie Database

- Marcel Ophüls's Hôtel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie (1988) at the Internet Movie Database

- Kevin Macdonald’s My Enemy’s Enemy (2007) at the Internet Movie Database

- L'avocat de la terreur at the Internet Movie Database (English: "Terror's Advocate")