Kingdom of Croatia (925–1102)

| Kingdom of Croatia | ||||||||||||||

| Regnum Croatiae | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Croatia at the height of its power | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Varied through time Nin, Biograd, Solin, Knin | |||||||||||||

| Languages | Old Croatian, Latin | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | |||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||||

| • | 925–928 | Tomislav (first)a | ||||||||||||

| • | 1093–1097 | Petar Svačić (last) | ||||||||||||

| Ban (Viceroy) | ||||||||||||||

| • | c. 949–969 | Pribina (first) | ||||||||||||

| • | c. 1075–1091 | Petar Svačić (last) | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||||||

| • | Elevation to kingdom | c. 925 | ||||||||||||

| • | Succession crisis and coronation of Coloman | 1102 | ||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||

| • | 11th century est. (mid) | 110,000 km² (42,471 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||

| a. | ^ Tomislav is regarded as the first king due to being addressed as Rex (King) in a letter sent by Pope John X and the Council conclusions of Split in 925 AD. Circumstances and the date of his coronation are unknown. The authenticity of the Papal letter has been questioned, but later inscriptions and charters confirm that his successors called themselves "kings".[1] | |||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Croatia (Latin: Regnum Croatiae; Croatian: Kraljevina Hrvatska, Hrvatsko Kraljevstvo) was a medieval kingdom in Central Europe comprising most of what is today Croatia (without most of Istria and some Dalmatian coastal cities), as well as parts of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Kingdom existed as a sovereign state for nearly two centuries. Its existence was characterized by various conflicts and periods of peace or alliance with the Bulgarians, Byzantines, Hungarians, and competition with Venice for control over the eastern Adriatic coast. The goal of promoting the Slavic language in the religious service was initially brought and introduced by the 10th century bishop Gregory of Nin, which resulted in a conflict with the Pope, later to be put down by him.[2] In the second half of the 11th century Croatia managed to secure most coastal cities of Dalmatia with the collapse of Byzantine control over them. During this time the kingdom reached its peak under the rule of kings Peter Krešimir IV (1058-1074) and Demetrius Zvonimir (1075-1089).

The state was ruled mostly by the Trpimirović dynasty until 1091. At that point the realm experienced a succession crisis and after a decade of conflicts for the throne and the aftermath of the Battle of Gvozd Mountain, the crown passed to the Árpád dynasty with the coronation of King Coloman of Hungary as "King of Croatia and Dalmatia" in Biograd in 1102, uniting the two kingdoms under one crown.[3][4][5][6] The precise terms of the relationship between the two realms became a matter of dispute in the 19th century.[7][8][9] The nature of the relationship varied through time, Croatia retained a large degree of internal autonomy overall, while the real power rested in the hands of the local nobility.[7][10][11] Modern Croatian and Hungarian historiographies mostly view the relations between Kingdom of Croatia and Kingdom of Hungary from 1102 as a form of a personal union of two internally autonomous kingdoms united by a common king.[12]

Name

The first official name of the country was "Kingdom of the Croats" (Latin: Regnum Croatorum; Croatian: Kraljevstvo Hrvata),[13] but over the course of time the name "Kingdom of Croatia" (Regnum Croatiae;[14] Kraljevina Hrvatska) prevailed in use.[13] From 1060, when Peter Krešimir IV gained control over coastal cities of the Theme of Dalmatia, earlier under the Byzantine Empire, the official and diplomatic name of the kingdom was "Kingdom of Croatia and Dalmatia" (Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae; Kraljevina Hrvatska i Dalmacija). Such form of the name lasted until the death of King Stephen II in 1091.[15][16]

Background

Arrival of Croats

The Slavs arrived in the early 7th century in what is Croatia today. No contemporary written records about the migration have been preserved, especially not about the events as a whole and from the area itself. Instead, historians rely on records written several centuries after the facts, and even those records may be based on oral tradition.

The Croats were a Slavic tribe, coming from an area in and around today's Poland or western Ukraine. Many modern scholars believe that the early Croat people, as well as other early Slavic groups, were agricultural populations that were ruled by the nomadic Iranian-speaking Alans. It is unclear whether the Alans contributed much more than a ruling caste or a class of warriors; the evidence on their contribution is mainly philological and etymological.

The large scale movements of Slavs are associated with the Avars, a nomadic Turkic group that had settled in the Carpathian basin in late 6th century, subjugating surrounding small Slavic tribes.[17] The book De Administrando Imperio ("On the Governance of the Empire"), written in the 10th century, is the most referenced source on the migration of Slavic peoples into southeastern Europe. It states that the Slavs migrated first around or before year 600 from the region that is now (roughly) Galicia and areas of the Pannonian plain, led by the Avars, to the province of Dalmatia ruled by the Roman Empire.

The second wave of migration, possibly around year 620,[18] began when the Croats were invited by the Emperor Heraclius to counter the Avar threat on the Byzantine Empire. The Emperor promised the Croats protection if they defeated the Avars, who had earlier expelled the population of Dalmatia.[19]

And so, by command of the emperor Heraclius these same Croats defeated and expelled the Avars from those parts, and by mandate of Heraclius the emperor they settled down in that same country of the Avars, where they now dwell.— Constantine Porphyrogenitus in De Administrando Imperio: 31. Of the Croats and of the country they now dwell in[19]

De Administrando Imperio also mentions an alternate version of the events, where the Croats weren't actually invited by Heraclius, but instead defeated the Avars and settled on their own accord after migrating from an area near today's Silesia. From those Croats who came to Dalmatia a part split off and settled in Illyricum and Pannonia. Furthermore, De Administrando Imperio reports a folk tradition that the Croats, who were at the time dwelling beyond Bavaria, were led into the province of Dalmatia by a group of five brothers, Klukas, Lobel, Kosenc, Muhlo and Hrvat, and their two sisters, Tuga and Buga.[20]

After they had fought one another for some years, the Croats prevailed and killed some of the Avars and the remainder they compelled to be subject to them. And so from that time this land was possessed by the Croats, and there are still in Croatia some who are of Avar descent and are recognized as Avars.— Constantine Porphyrogenitus in De Administrando Imperio: 30. Story of the province of Dalmatia[20]

Thomas the Archdeacon, as well as the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja from the 12th century, state that the Croats remained after the Goths (under a leader referred to as "Totila") had occupied and pillaged the Roman province of Dalmatia. The Chronicle speaks of a Gothic invasion (under a leader referred to as "Svevlad", followed by his descendants "Selimir" and "Ostroilo"). Archdeacon Thomas in his work Historia Salonitana from the 13th century mentions that with Totila, who destroyed the city of Salona and ravaged Dalmatia, came seven or eight tribes of nobles which he called "Lingones" from what is today Poland and settled in Croatia.[21]

Christianization

The earliest record of contact between the Roman Pope and the Croats dates from a mid-7th century entry in the Liber Pontificalis. Pope John IV (John the Dalmatian, 640-642) sent an abbot named Martin to Dalmatia and Istria in order to pay ransom for some prisoners and for the remains of old Christian martyrs. This abbot is recorded to have travelled through Dalmatia with the help of the Croatian leaders, and he established the foundation for the future relations between the Pope and the Croats.

The Christianization of the Croats began after their arrival, probably in the 7th century, influenced by the proximity of the old Roman cities in Dalmatia. The process was completed in the north by the beginning of the 9th century. The beginnings of the Christianization are also disputed in the historical texts: the Byzantine texts talk of duke Porin who started this at the incentive of emperor Heraclius, then of Porga who mainly Christianized his people after the influence of missionaries from Rome, while the national tradition recalls Christianization during the rule of Duke Borna. It is possible that these are all renditions of the same ruler's name.

The Croats, apart from Latin, also held masses in their own language and used the Glagolitic alphabet. This was officially sanctioned in 1248 by Pope Innocent IV, and only later did the Latin alphabet prevail.

The Latin Rite prevailed over the Byzantine Rite rather early due to numerous interventions from the Holy See. There were numerous church synods held in Dalmatia in the 11th century, particularly after the East-West Schism, during the course of which the use of the Latin rite was continuously reinforced until it became dominant.

Early Croatian states

Croatian lands in the Dark Ages were located between three major entities: the Eastern Roman Empire which aimed to control the Dalmatian city-states and islands, the Franks which aimed to control the northern and northwestern lands, and the Avars, later Magyars, and other fledgling states in the northeast. The fourth relevant group, but not so powerful with regard to the Croatian state, were the nearby Slavs in the southeast, the Serbs and the Bulgarians.

The north became subject to the Carolingian Empire around 800, when in 796 Croatian Pannonian prince Vojnomir switched sides between the Avars and the Franks. The Franks established control over the region between Sava, Drava and Danube which was under the Margrave of Friuli. The Patriarchy of Aquileia was then allowed to Christianize the remaining Slavs in the region. Charlemagne invaded the Dalmatian portion of Croatia in 799, contesting its Byzantine suzerainty. Although the Franks lost the siege of Trsat, from 803, Frankish overlordship was recognized in most of northern Dalmatia.[22]

Charlemagne's invasion of the Dalmatian cities provoked a war with the Eastern Roman Empire — after a peace deal was signed, the Byzantine Empire restored the city-states and islands while Charlemagne kept Istria and inland Dalmatia. After the death of Charlemagne in 814, the Frankish influence decreased, and Ljudevit Posavski raised a rebellion in Pannonia in 819.[22][23] At the time the Duchy of Croatia was ruled by Borna, who was on the side of the Franks in the war. This led to an open conflict between Borna and Ljudevit in which Borna was defeated in the battle of Kupa in 819.[22] The Frankish Margraves sent armies in 820, 821 and 822, but each time they failed to crush the rebels until finally Ljudevit's forces withdrew to Bosnia. Most of the Duchy of Pannonia would remain in Frankish suzerainty until the end of the 9th century. What is today eastern Slavonia and Syrmia fell to the Bulgarians in 827 after a border dispute with the Franks. By a peace treaty in 845, the Franks were confirmed as rulers over Slavonia, whilst Syrmia remained under Bulgarian clientage.

In the meantime, the Dalmatian Croats were recorded to have been subject to the Kingdom of Italy under Lothair I, since 828. Duke Mislav of Croatia (c. 835–845) built up a formidable navy, and in 839 signed a peace treaty with Pietro Tradonico, doge of Venice. The Venetians soon proceeded to battle with the Narentine pirates, but failed to defeat them.[24] Duke Trpimir I succeeded Mislav in around 845 and in 846 successfully attacked the Byzantine coastal cities in Dalmatia.[25] In 855 Boris I of Bulgaria attacked Dalmatian Croatia trying to expand his state to the Adriatic, but was defeated probably in Eastern Bosnia and signed a peace treaty with Trpimir.[26] Trpimir I managed to consolidate power over Dalmatia and much of the inland regions towards Pannonia, while instituting counties as a way of controlling his subordinates (an idea he picked up from the Franks). The first known written mention of the Croats is from a Latin charter issued by Trpimir dated 4 March 852.[27][28] Trpimir is remembered as the initiator of the Trpimirović dynasty that ruled in Croatia, with interruptions, from 845 until 1091.

In the meantime, the Saracens, a group of Arab pirates, invaded Taranto and Bari in the 840s. The extent of their piracy forced the Byzantium to increase its military presence in the southern Adriatic. In 867 a Byzantine fleet lifted the Saracen siege over Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik) and also defeated the Narentine pirates.[29]

Facing a number of naval threats, Duke Domagoj (864–876) built up the Croatian navy again and helped the Franks conquer Bari from the Arabs in 871.[29][30] During his reign piracy was a common practice in the Adriatic.[31] The Croatian vessels also fought wars against the Venetians and the Franks. Domagoj led a successful revolt against the Frankish Empire, ending their overlordship over Croatia.[32] Domagoj's forces attacked the western Istrian towns in 876,[33] but were subsequently defeated by the Venetian navy.[32] His ground forces defeated the Pannonian duke Kocelj (861–874) who was suzerain to the Franks, and thereby shed the Frankish vassal status. Domagoj was succeeded by his son, of unknown name, who ruled Croatia between 876 and 878.

The next Duke, Zdeslav (878–879), overthrew Domagoj's son,[34] but reigned briefly, only to see the Byzantine Empire conquer large portions of Dalmatia. He was then overthrown by Duke Branimir (879–892), who was supported by the Western Church. Branimir was the first Croatian ruler under which Croatia received recognition as a sovereign state, recognised by Pope John VIII in 879.[32] On a preserved inscription from 888 Branimir was named "Duke of Croats" (Latin: Dux Cruatorvm). Branimir proceeded to repel the Byzantine incursion and strengthen his state under the ægis of Rome. After Branimir's death, Duke Muncimir (892–910), Zdeslav's brother, took control of Croatia and ruled it independently of both Rome and Byzantium as divino munere Croatorum dux (with God's help, duke of the Croats).

The last Duke of the Pannonian Croats under the Franks was Braslav (died in 897?), mentioned in 896, who died in a war with the Magyars, who then migrated to the Pannonian plain. In Dalmatia, Duke Tomislav (910–928) succeeded Muncimir. Tomislav vaged battles with the Magyars and expanded his country to the north. In about 923 the Byzantines, who were at the time in a war with the Bulgarians, concluded an alliance with Croatia.

Kingdom

Establishment

Croatia was elevated to the status of Kingdom somewhere around 925. Tomislav was the first Croatian ruler whom the Papal chancellery honoured with the title "king".[35] It is generally said that Tomislav was crowned in 925, however, this is not certain. He is thought to have been crowned in Tomislav Grad, which is in modern-day southwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is not known when, or by whom he was crowned, or was he crowned at all.[1] Tomislav is mentioned as a king in two preserved documents published in the Historia Salonitana. First in a note preceding the text of the conclusions of the Council of Split in 925, where it is written that Tomislav is the "king" ruling "in the province of the Croats and in the Dalmatian regions" (in prouintia Croatorum et Dalmatiarum finibus Tamisclao rege),[36][37][38] while in the 12th canon of the Council conclusions the ruler of the Croats is called "king" (rex et proceres Chroatorum).[38] In a letter sent by the Pope John X Tomislav is named "King of the Croats" (Tamisclao, regi Crouatorum).[36][39] The Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja titled Tomislav as a king and specified his rule at 13 years.[36] Although there are no inscriptions of Tomislav to confirm the title, later inscriptions and charters confirm that his 10th century successors called themselves "kings".[37] Under his rule, Croatia became one of the most powerful kingdoms in the Balkans.[40][41]

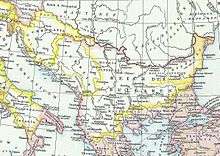

Tomislav, a descendant of Trpimir I, is considered one of the most prominent members of the Trpimirović dynasty. Sometime between 923 and 928, Tomislav succeeded in uniting the Croats of Pannonia and Dalmatia, each of which had been ruled separately by dukes. Although the exact geographical extent of Tomislav's kingdom is not fully known, Croatia probably covered most of Dalmatia, Pannonia, and northern and western Bosnia.[42] Croatia at the time was administered as a group of eleven counties (županije) and one banate (Banovina). Each of these regions had a fortified royal town.

Croatia soon came into conflict with the Bulgarian Empire under Simeon I (called Simeon the Great in Bulgaria), who was already in a war with the Byzantines. Tomislav made a pact with the Byzantine Empire, for which he may have been rewarded by the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos with some form of control over the coastal cities of the Byzantine Theme of Dalmatia and with a share of the tribute collected from its coastal cities.[37] After Simeon conquered the Principality of Serbia in 924, Croatia received and protected the expelled Serbs with their leader Zaharija.[43] In 926, Simeon tried to break the Croatian-Byzantine pact and afterwards conquer the weakly defended Byzantine Theme of Dalmatia,[44] sending Duke Alogobotur with a formidable army against Tomislav, but Simeon's army was defeated in the Battle of the Bosnian Highlands. After Simeon's death in 927 peace was restored between Croatia and Bulgaria with the mediation of the legates of Pope John X.[45] According to the contemporary De Administrando Imperio, Croatian army and navy at the time could have consisted of approximately 100,000 infantry units, 60,000 cavaliers, and 80 larger (sagina) and 100 smaller warships (condura),[46] but these numbers are generally taken as a considerable exaggeration.[42]

10th century

Croatian society underwent major changes in the 10th century. Local leaders, the župani, were replaced by the retainers of the king, who took land from the previous landowners, essentially creating a feudal system. The previously free peasants became serfs and ceased being soldiers, causing the military power of Croatia to fade.

Tomislav was succeeded by Trpimir II (c. 928–935) and Krešimir I (c. 935–945), who each managed to maintain their power and keep good relations with both the Byzantine Empire and the Pope. This period, on the whole, however, is obscure. The rule of Krešimir's son Miroslav was marked by a gradual weakening of Croatia.[47] Various peripheral territories took advantage of unsettled conditions to secede.[48] Miroslav ruled for 4 years when he was killed by his ban, Pribina, during an internal power struggle. Pribina secured the throne to Michael Krešimir II (949–969), who restored order throughout most of the state. He kept particularly good relations with the Dalmatian coastal cities, he and his wife Helen donating land and churches to Zadar and Solin. Michael Krešimir's wife Helen built the Church of Saint Mary in Solin that served as the tomb of Croatian rulers. Helen died on 8 October 976 and was buried in that church, where a royal inscription on her sarcophagus was found that called her "Mother of the Kingdom".[49][50]

Michael Krešimir II was succeeded by his son Stephen Držislav (969–997), who established better relations with the Byzantine Empire and their Theme of Dalmatia. According to Historia Salonitana, Držislav received royal insignia from the Byzantines, together with the title of eparch and patricius. Also, according to this work, from the time of Džislav's reign his successors called themselves kings of Croatia and Dalmatia. Stone panels from the altar of a 10th-century church in Knin with the inscription of Držislav, possibly when he was the heir to the throne, show that there was a precisely defined hierarchy regulating the matters of succession to the throne.[50]

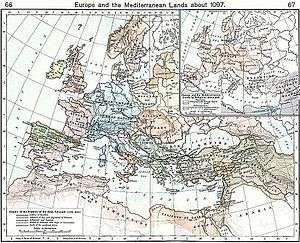

11th century

As soon as Stjepan Držislav had died in 997, his three sons, Svetoslav (997–1000), Krešimir III (1000–1030), and Gojslav (1000–1020), opened a violent contest for the throne, weakening the state and allowing the Venetians under Pietro II Orseolo and the Bulgarians under Samuil to encroach on the Croatian possessions along the Adriatic. In 1000, Orseolo led the Venetian fleet into the eastern Adriatic and gradually took control of the whole of it,[51] first the islands of the Gulf of Kvarner and Zadar, then Trogir and Split, followed by a successful naval battle with the Narentines upon which he took control of Korčula and Lastovo, and claimed the title dux Dalmatiæ. Krešimir III tried to restore the Dalmatian cities and had some success until 1018, when he was defeated by Venice allied with the Lombards. The same year his kingdom briefly became a vassal of the Byzantine Empire until 1025 and the death of Basil II.[52] His son, Stjepan I (1030–1058), only went so far as to get the Narentine duke to become his vassal in 1050.

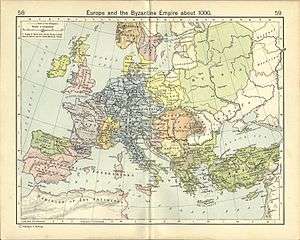

During the reign of Krešimir IV (1058–1074), the medieval Croatian kingdom reached its territorial peak. Krešimir managed to get the Byzantine Empire to confirm him as the supreme ruler of the Dalmatian cities, i.e. over the Theme of Dalmatia, excluding the theme of Dubrovnik and the Duchy of Durazzo.[53] He also allowed the Roman curia to become more involved in the religious affairs of Croatia, which consolidated his power but disrupted his rule over the Glagolitic clergy in parts of Istria after 1060. Croatia under Krešimir IV was composed of twelve counties and was slightly larger than in Tomislav's time. It included the closest southern Dalmatian duchy of Pagania, and its influence extended over Zahumlje, Travunia, and Duklja.

However, in 1072, Krešimir assisted the Bulgarian and Serb uprising against their Byzantine masters. The Byzantines retaliated in 1074 by sending the Norman count Amico of Giovinazzo to besiege Rab. They failed to capture the island, but did manage to capture the king himself, and the Croatians were then forced to settle and give away Split, Trogir, Zadar, Biograd, and Nin to the Normans. In 1075, Venice expelled the Normans and secured the cities for itself. The end of Krešimir IV in 1074 also marked de facto end of the Trpimirović dynasty, which had ruled the Croatian lands for over two centuries.

According to the Supetar Cartulary, a new king was elected by seven bans (if the previous one died without a successor e.g. Krešimir IV): ban of Croatia, ban of Bosnia, ban of Slavonia etc.[54] The bans were elected by the first six Croatian tribes, while the other six were responsible for choosing župans.

Krešimir was succeeded by Demetrius Zvonimir (1075–1089) of the Svetoslavić branch of the House of Trpimirović. He was previously a ban in Slavonia in the service of Peter Krešimir IV and later the Duke of Croatia. He gained the title of king with the support of Pope Gregory VII and was crowned as King of Croatia in Solin on 8 October 1076. Zvonimir aided the Normans under Robert Guiscard in their struggle against the Byzantine Empire and Venice between 1081 and 1085. Zvonimir helped to transport their troops through the Strait of Otranto and to occupy the city of Dyrrhachion. His troops assisted the Normans in many battles along the Albanian and Greek coast. Due to this, in 1085, the Byzantines transferred their rights in Dalmatia to Venice.

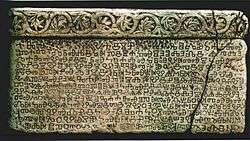

Zvonimir's kinghood is carved in stone on the Baška Tablet, preserved to this day as one of the oldest written Croatian texts, kept in the archæological museum in Zagreb. Zvonimir's reign is remembered as a peaceful and prosperous time, during which the connection of Croats with the Holy See was further affirmed, so much so that Catholicism would remain among Croats until the present day. In this time the noble titles in Croatia were made analogous to those used in other parts of Europe at the time, with comes and baron used for the župani and the royal court nobles, and vlastelin for the noblemen. The Croatian state was edging closer to western Europe and further from the east.

Demetrius Zvonimir married Helen of Hungary in 1063. Queen Helen was a Hungarian princess, the daughter of King Béla I of the Hungarian Árpád dynasty, and was the sister of the future Hungarian King Ladislaus I. Zvonimir and Helen had a son, Radovan, who died in his late teens or early twenties. King Demetrius Zvonimir died in 1089. The exact circumstances of his death are unknown. According to a later, likely unsubstantiated legend, King Zvonimir was killed during a revolt in 1089.[55]

There was no permanent state capital, as the royal residence varied from one ruler to another; five cities in total reportedly obtained the title of a royal seat: Nin (Krešimir IV), Biograd (Stephen Držislav, Krešimir IV), Knin (Zvonimir, Petar Svačić), Šibenik (Krešimir IV), and Solin (Krešimir II).[56]

Succession crisis

With no direct heir to succeed him, Stephen II (reigned 1089–1091) of the main Trpimirović line came to the throne at an old age. Stephen II was to be the last King of the House of Trpimirović. His rule was relatively ineffectual and lasted less than two years. He spent most of this time in the tranquility of the monastery of Sv. Stjepan pod Borovima (St. Stephen beneath the Pines) near Split. He died at the beginning of 1091, without leaving an heir. Since there was no living male member of the House of Trpimirović, civil war and unrest broke out shortly afterward.[57]

The widow of late King Zvonimir, Helen, tried to keep her power in Croatia during the succession crisis.[58] Some Croatian nobles around Helen, possibly the Gusići[59] and/or Viniha from Lapčani family,[58] contesting the succession after the death of Zvonimir, asked King Ladislaus I to help Helen and offered him the Croatian throne, which was seen as rightfully his by inheritance rights. According to some sources, several Dalmatian cities also asked King Ladislaus for assistance, presenting themselves as White Croats on his court.[59] Thus the campaign launched by Ladislaus was not purely a foreign aggression[60] nor did he appear on the Croatian throne as a conqueror, but rather as a successor by hereditary rights.[61] In 1091 Ladislaus crossed the Drava river and conquered the entire province of Slavonia without encountering opposition, but his campaign was halted near the Iron Mountains (Mount Gvozd).[62] Since the Croatian nobles were divided, Ladislaus had success in his campaign, yet he wasn't able to establish his control over entire Croatia, although the exact extent of his conquest is not known.[59][60] At this time the Kingdom of Hungary was attacked by the Cumans, who were likely sent by the Byzantium, so Ladislaus was forced to retreat from his campaign in Croatia.[59] Ladislaus appointed his nephew Prince Álmos to administer the controlled area of Croatia, established the diocese of Zagreb as a symbol of his new authority and went back to Hungary. In the midst of the war, Petar Svačić was elected king by Croatian feudal lords in 1093. Petar's seat of power was based in Knin. His rule was marked by a struggle for control of the country with Álmos, who wasn't able to establish his rule and was forced to withdraw to Hungary in 1095.[63]

Ladislaus died in 1095, leaving his nephew Coloman to continue the campaign. Coloman, as well as Ladislaus before him, wasn't seen as a conqueror but rather as a pretender to the Croatian throne.[64] Coloman assembled a large army to press his claim on the throne and in 1097 defeated King Petar's troops in the Battle of Gvozd Mountain, who was killed in battle. Since the Croatians didn't have a leader any more and Dalmatia had numerous fortified towns that would be difficult to defeat, negotiations started between Coloman and the Croatian feudal lords. It took several more years before the Croatian nobility recognised Coloman as the king. Coloman was crowned in Biograd in 1102 and the title now claimed by Coloman was "King of Hungary, Dalmatia, and Croatia". Some of the terms of his coronation are summarized in Pacta Conventa by which the Croatian nobles agreed to recognise Coloman as king. In return, the 12 Croatian nobles that signed the agreement retained their lands and properties and were granted exemption from tax or tributes. The nobles were to send at least ten armed horsemen each beyond the Drava River at the kings expense if his borders were attacked.[65][66] Despite that Pacta Conventa is not an authentic document from 1102, there was almost certainly some kind of contract or agreement between the Croatian nobles and Coloman which regulated the relations in the same way.[60][67][68]

Unification

In 1102, after a succession crisis, the crown passed into the hands of the Árpád dynasty, with the crowning of King Coloman of Hungary as "King of Croatia and Dalmatia" in Biograd. The precise terms of the union between the two realms became a matter of dispute in the 19th century.[9] The two kingdoms were united under the Árpád dynasty either by the choice of the Croatian nobility or by Hungarian force.[70] Croatian historians hold that the union was a personal one in the form of a shared king, a view also accepted by a number of Hungarian historians,[6][12][60][64][71][72] while Serbian and Hungarian nationalist historians preferred to see it as a form of annexation.[8][9][73] The claim of a Hungarian occupation was made in the 19th century during the Hungarian national reawakening.[73] Thus in older Hungarian historiography Coloman's coronation in Biograd was a subject of dispute and their stance was that Croatia was conquered. Although these kind of claims can also be found today, since the Croatian-Hungarian tensions are gone, it has generally been accepted that Coloman was crowned in Biograd for king.[74] Today, Hungarian legal historians hold that the relationship of Hungary with the area of Croatia and Dalmatia in the period till 1526 and the death of Louis II was most similar to a personal union,[12][75] resembling the relationship of Scotland to England.[76][77]

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations and the Grand Larousse encyclopédique, Croatia entered a personal union with Hungary in 1102, which remained the basis of the Hungarian-Croatian relationship until 1918,[3][78] while Encyclopædia Britannica specified the union as a dynastic one.[67] According to the research of the Library of Congress, Coloman crushed opposition after the death of Ladislaus I and won the crown of Dalmatia and Croatia in 1102, thus forging a link between the Croatian and Hungarian crowns that lasted until the end of World War I.[79] Hungarian culture permeated northern Croatia, the Croatian-Hungarian border shifted often, and at times Hungary treated Croatia as a vassal state. Croatia had its own local governor, or Ban; a privileged landowning nobility; and an assembly of nobles, the Sabor.[79] According to some historians, Croatia became part of Hungary in the late 11th and early 12th century,[80] yet the actual nature of the relationship is difficult to define.[73] Sometimes Croatia acted as an independent agent and at other times as a vassal of Hungary.[73] However, Croatia retained a large degree of internal independence.[73] The degree of Croatian autonomy fluctuated throughout the centuries as did its borders.[10]

The alleged agreement called Pacta conventa (English: Agreed accords) or Qualiter (first word of the text) is today viewed as a 14th-century forgery by most modern Croatian historians. According to the document King Coloman and the twelve heads of the Croatian nobles made an agreement, in which Coloman recognised their autonomy and specific privileges. Although it is not an authentic document from 1102, nonetheless there was at least a non-written agreement that regulated the relations between Hungary and Croatia in approximately the same way,[60][67] while the content of the alleged agreement is concordant with the reality of rule in Croatia in more than one respect.[69]

The official entering of Croatia into a personal union with Hungary, becoming part of the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen, had several important consequences. Institutions of separate Croatian statehood were maintained with the Sabor (parliament) and the ban (viceroy)[67] in the name of the king. A single ban governed all Croatian provinces until 1225, when the authority was split between one ban of the whole of Slavonia and one ban of Croatia and Dalmatia. The positions were intermittently held by the same person after 1345, and officially merged back into one by 1476.

Union with Hungary

In the union with Hungary, the crown was held by the Arpad dynasty, and after its extinction, under Anjou dynasty. Institutions of separate Croatian statehood were maintained through the Parliament (Croatian: Sabor - an assembly of Croatian nobles) and the ban (viceroy) responsible to the King of Hungary and Croatia. In addition, the Croatian nobles retained their lands and titles.[67] Coloman retained the institution of the Sabor and relieved the Croatians of taxes on their land. Coloman's successors continued to crown themselves as Kings of Croatia separately in Biograd na Moru until the time of Béla IV.[81] In the 14th century a new term arose to describe the collection of de jure independent states under the rule of the Hungarian King: Archiregnum Hungaricum (Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen).[82] Croatia remained a distinct crown attached to that of Hungary until the abolition of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918.

See also

- Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg)

- Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia

- History of Croatia

- Pacta conventa (Croatia)

- Crown of Zvonimir

- Bans of Croatia

- Timeline of Croatian history

References

- 1 2 Van Antwerp Fine, John (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans. University of Michigan Press. p. 264. ISBN 0472081497.

- ↑ (Croatian) Hrvatski glagoljizam i stradanje dalmatinskih gradova

- 1 2 Larousse online encyclopedia, Histoire de la Croatie: "Liée désormais à la Hongrie par une union personnelle, la Croatie, pendant huit siècles, formera sous la couronne de saint Étienne un royaume particulier ayant son ban et sa diète." (French)

- ↑ Clifford J. Rogers: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 293

- ↑ Luscombe and Riley-Smith, David and Jonathan (2004). New Cambridge Medieval History: C.1024-c.1198, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. pp. 273–274. ISBN 0-521-41411-3.

- 1 2 Kristó Gyula: A magyar–horvát perszonálunió kialakulása [The formation of Croatian-Hungarian personal union](in Hungarian)

- 1 2 Bellamy, Alex J. (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity. Manchester University Press. pp. 36–39. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- 1 2 Jeffries, Ian (1998). A History of Eastern Europe. Psychology Press. p. 195. ISBN 0415161126. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Sedlar, Jean W. (2011). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages. University of Washington Press. p. 280. ISBN 029580064X. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- 1 2 Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- ↑ John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 288

- 1 2 3 Barna Mezey: Magyar alkotmánytörténet, Budapest, 1995, p. 66

- 1 2 Ferdo Šišić: Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, p. 651

- ↑ Monumenta spectantia historiam Slavorum meridionalium, Edidit Academia Scienciarum et Artium Slavorum Meridionalium vol VIII, Zagreb, 1877, p. 199

- ↑ Lujo Margetić: Hrvatska i Crkva u srednjem vijeku, Pravnopovijesne i povijesne studije, Rijeka, 2000, p. 88-92

- ↑ Lujo Margetić: Regnum Croatiae et Dalmatiae u doba Stjepana II., p. 19

- ↑ John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 30-31

- ↑ Croatia - historical and cultural overview. Darko Zubrinic, Zagreb (1995).

- 1 2 De Administrando Imperio: 31. Of the Croats and of the country they now dwell in. "These same Croats arrived to claim the protection of the emperor of the Romans Heraclius before the Serbs claimed the protection of the same emperor Heraclius, at that time when the Avars had fought and expelled from those parts the Romani whom the emperor Diocletian had brought from Rome and settled there"

- 1 2 De Administrando Imperio: 30. Story of the province of Dalmatia

- ↑ Thomas Archidiaconus Spalatensis: Historia Salonitanorum Atque Spalatinorum Pontificum p. 35-37

- 1 2 3 John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 251-255

- ↑ Annales regni Francorum DCCCXVIIII (year 819)

- ↑ Iohannes Diaconus, Istoria Veneticorum, p. 124 (Latin)

- ↑ Nada Klaić, Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, Zagreb 1975., p. 227-231

- ↑ De Administrando Imperio, 31. Of the Croats and of the country they now dwell in. "...when Michael Boris, prince of Bulgaria, went and fought them and, unable to make any headway, concluded peace with them, and made presents to the Croats and received presents from the Croats."

- ↑ Florin Curta: Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250, Cambridge University Press. 2006, p. 139

- ↑ Codex Diplomaticus Regni Croatiæ, Dalamatiæ et Slavoniæ, Vol I, p. 4-8

- 1 2 Neven Budak – Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., page 15-16 (Croatian)

- ↑ De Administrando Imperio: 29. Of Dalmatia and of the adjacent nations in it.

- ↑ Maddalena Betti: The Making of Christian Moravia (858-882), 2013, p. 128-130

- 1 2 3 John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 261

- ↑ Nada Klaić: Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, II Izdanje, Zagreb 1975., p. 247

- ↑ Iohannes Diaconus, Istoria Veneticorum, p. 140 (Latin)

- ↑ Neven Budak - Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., p. 22

- 1 2 3 Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 274-275

- 1 2 3 Florin Curta: Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250, Cambridge University Press. 2006, p. 196

- 1 2 Codex Diplomaticus Regni Croatiæ, Dalamatiæ et Slavoniæ, Vol I, p. 32

- ↑ Codex Diplomaticus Regni Croatiæ, Dalamatiæ et Slavoniæ, Vol I, p. 34

- ↑ Opća enciklopedija JLZ. Yugoslavian Lexicographical Institute. Zagreb. 1982.

- ↑ (Croatian) Zoran Lukić - Hrvatska Povijest

- 1 2 John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 262

- ↑ De Administrando Imperio: XXXII. Of the Serbs and of the country they now dwell in

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 289-291

- ↑ Clifford J. Rogers: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, p. 162

- ↑ De Administrando Imperio: 31. Of the Croats and of the country they now dwell in. "Baptized Croatia musters as many as 60 thousand horse and 100 thousand foot, and galleys up to 80 and cutters up to 100."

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 302

- ↑ John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 265

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein: Hrvatski rani srednji vijek, Zagreb, 1995, p. 314-315

- 1 2 Neven Budak – Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., p. 24-25

- ↑ festa della sensa - Veniceworld.com

- ↑ Donald MacGillivray Nicol (1992). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 43, 55

- ↑ John Van Antwerp Fine: The Early Medieval Balkans: A critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, 1991, p. 279

- ↑ Povijesni pabirci hercegbosna.org.

- ↑ (Croatian) Kletva kralja Zvonimira nad hrvatskim narodom

- ↑ Ferdo Šišić, Povijest Hrvata; pregled povijesti hrvatskog naroda 600. - 1918., Zagreb ISBN 953-214-197-9

- ↑ Neven Budak - Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., page 77

- 1 2 Neven Budak - Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., page 80 (in Croatian)

- 1 2 3 4 Nada Klaić: Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, II Izdanje, Zagreb 1975., page 492 (in Croatian)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bárány, Attila (2012). "The Expansion of the Kingdom of Hungary in the Middle Ages (1000–1490)". In Berend, Nóra. The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Ashgate Variorum. page 344-345

- ↑ Márta Font - Ugarsko Kraljevstvo i Hrvatska u srednjem vijeku (Hungarian Kingdom and Croatia in the Middlea Ages), p. 8-9

- ↑ Archdeacon Thomas of Split: History of the Bishops of Salona and Split (ch. 17.), p. 93.

- ↑ Nada Klaić: Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, II Izdanje, Zagreb 1975., page 508-509 (in Croatian)

- 1 2 Ladislav Heka (October 2008). "Hrvatsko-ugarski odnosi od sredinjega vijeka do nagodbe iz 1868. s posebnim osvrtom na pitanja Slavonije" [Croatian-Hungarian relations from the Middle Ages to the Compromise of 1868, with a special survey of the Slavonian issue]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). Hrvatski institut za povijest – Podružnica za povijest Slavonije, Srijema i Baranje. 8 (1): 152–173. ISSN 1332-4853.

- ↑ Trpimir Macan: Povijest hrvatskog naroda, 1971, p. 71 (full text of Pacta conventa in Croatian)

- ↑ Ferdo Šišić: Priručnik izvora hrvatske historije, Dio 1, čest 1, do god. 1107., Zagreb 1914., p. 527-528 (full text of Pacta conventa in Latin)

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Croatia (History)". Britannica.

- ↑ Neven Budak - Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994., page 39 (in Croatian)

- 1 2 Pál Engel: Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 2005, p. 35-36

- ↑ "Croatia (History)". Encarta. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009.

- ↑ Márta Font - Ugarsko Kraljevstvo i Hrvatska u srednjem vijeku [Hungarian Kingdom and Croatia in the Middlea Ages] "Medieval Hungary and Croatia were, in terms of public international law, allied by means of personal union created in the late 11th century."

- ↑ Lukács István - A horvát irodalom története, Budapest, Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, 1996.[The history of Croatian literature](in Hungarian)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bellamy, Alex J. (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity. Manchester University Press. pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Klaić, Nada (1975). Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku [History of the Croats in the Early Middle Ages]. p. 513.

- ↑ Heka, László (October 2008). "Hrvatsko-ugarski odnosi od sredinjega vijeka do nagodbe iz 1868. s posebnim osvrtom na pitanja Slavonije" [Croatian-Hungarian relations from the Middle Ages to the Compromise of 1868, with a special survey of the Slavonian issue]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). 8 (1): 155.

- ↑ Jeszenszky, Géza. "Hungary and the Break-up of Yugoslavia: A Documentary History, Part I.". Hungarian Review. II (2).

- ↑ Banai Miklós, Lukács Béla: Attempts for closing up by long range regulators in the Carpathian Basin

- ↑ Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations | 2007 - Croatia

- 1 2 Curtis, Glenn E. (1992). "A Country Study: Yugoslavia (Former) - The Croats and Their Territories". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ↑ Power, Daniel (2006). The Central Middle Ages: Europe 950-1320. Oxford University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-19-925312-8.

- ↑ Curta, Stephenson, p. 267

- ↑ Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

Further reading

- Neven Budak - Prva stoljeća Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1994. (Croatian)

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- John Van Antwerp Fine Jr.: The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century, University of Michigan Press, 1991

- Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A short history of the Yugoslav peoples. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Curtis, Glenn E. (1992). "A Country Study: Yugoslavia (Former) - The Croats and Their Territories". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

.jpg)