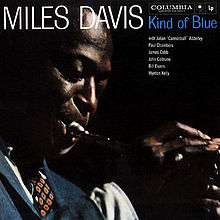

Kind of Blue

| Kind of Blue | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Miles Davis | ||||

| Released | August 17, 1959 | |||

| Recorded | March 2 and April 22, 1959 | |||

| Studio | Columbia 30th Street Studio in New York City | |||

| Genre | Modal jazz | |||

| Length | 45:44 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Teo Macero, Irving Townsend | |||

| Miles Davis chronology | ||||

| ||||

Kind of Blue is a studio album by American jazz musician Miles Davis, released on August 17, 1959, by Columbia Records. It was recorded earlier that year on March 2 and April 22 at Columbia's 30th Street Studio in New York City. The recording sessions featured Davis's ensemble sextet, consisting of pianist Bill Evans, drummer Jimmy Cobb, bassist Paul Chambers, and saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian "Cannonball" Adderley, together with pianist Wynton Kelly on one track.

After the entry of Evans into his sextet, Davis followed up on the modal experimentations of Milestones (1958) by basing Kind of Blue entirely on modality, in contrast to his earlier work with the hard bop style of jazz.

Though precise figures have been disputed, Kind of Blue has been described by many music writers not only as Davis's best-selling album, but as the best-selling jazz record of all time. On October 7, 2008, it was certified quadruple platinum in sales by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).

Kind of Blue has been regarded by many critics as jazz's greatest record, Davis's masterpiece, and one of the best albums of all time. Its influence on music, including jazz, rock, and classical genres, has led writers to also deem it one of the most influential albums ever recorded. Kind of Blue was one of fifty recordings chosen in 2002 by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry, and in 2003, it was ranked number 12 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Background

By late 1958, Davis employed one of the most acclaimed and profitable working bands pursuing the hard bop style. His personnel had become stable: alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, pianist Bill Evans, long-serving bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb. His band played a mixture of pop standards and bebop originals by Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and Tadd Dameron. As with all bebop-based jazz, Davis's groups improvised on the chord changes of a given song.[1] Davis was one of many jazz musicians growing dissatisfied with bebop, and saw its increasingly complex chord changes as hindering creativity.[2]

In 1953, the pianist George Russell published his Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization,[3] which offered an alternative to the practice of improvisation based on chords and chord changes. Abandoning the traditional major and minor key relationships, the Lydian Chromatic Concept introduced the idea of chord/scale unity and was the first theory to explore the vertical relationship between chords and scales, as well as the only original theory to come from jazz. This approach led the way to "modal" in jazz.[4] Influenced by Russell's ideas, Davis implemented his first modal composition with the title track of his studio album Milestones (1958). Satisfied with the results, Davis prepared an entire album based on modality.[5] Pianist Bill Evans, who had studied with Russell but recently departed from Davis's sextet to pursue his own career, was drafted back into the new recording project, the sessions that would become Kind of Blue.[6]

Recording

It must have been made in heaven.

Kind of Blue was recorded on three-track tape in two sessions at Columbia Records' 30th Street Studio in New York City. On March 2, 1959, the tracks "So What", "Freddie Freeloader", and "Blue in Green" were recorded for side one of the original LP, and on April 22 the tracks "All Blues" and "Flamenco Sketches" were recorded, making up side two. Production was handled by Teo Macero, who had produced Davis's previous two LPs, and Irving Townsend.[8]

As was Davis's penchant, he called for almost no rehearsal and the musicians had little idea what they were to record. As described in the original liner notes by pianist Bill Evans, Davis had only given the band sketches of scales and melody lines on which to improvise.[7] Once the musicians were assembled, Davis gave brief instructions for each piece and then set to taping the sextet in studio. While the results were impressive with so little preparation, the persistent legend that the entire album was recorded in one pass is untrue.[7] Only "Flamenco Sketches" yielded a complete take on the first try. That take, not the master, was issued in 1997 as a bonus alternate take.[7] The five master takes issued, however, were the only other complete takes; an insert for the ending to "Freddie Freeloader" was recorded, but was not used for release or on the issues of Kind of Blue prior to the 1997 reissue.[7] Pianist Wynton Kelly may not have been happy to see the man he replaced, Bill Evans, back in his old seat. Perhaps to assuage the pianist's feelings, Davis had Kelly play instead of Evans on the album's most blues-oriented number, "Freddie Freeloader".[7] The live album Miles Davis at Newport 1958 documents this band. However, the Newport Jazz Festival recording on July 3, 1958, reflects the band in its hard bop conception, the presence of Bill Evans only six weeks into his brief tenure in the Davis band notwithstanding, rather than the modal approach of Kind of Blue.[9]

Composition

Kind of Blue is based entirely on modality in contrast to Davis's earlier work with the hard bop style of jazz and its complex chord progression and improvisation.[5] The entire album was composed as a series of modal sketches, in which each performer was given a set of scales that defined the parameters of their improvisation and style.[10] This style was in contrast to more typical means of composing, such as providing musicians with a complete score or, as was more common for improvisational jazz, providing the musicians with a chord progression or series of harmonies.[2]

Modal jazz of this type was not unique to this album. Davis himself had previously used the same method on his 1958 Milestones album, the '58 Sessions, and Porgy and Bess (1958), on which he used modal influences for collaborator Gil Evans's third stream compositions.[2] Also, the original concept and method had been developed in 1953 by pianist and writer George Russell. Davis saw Russell's methods of composition as a means of getting away from the dense chord-laden compositions of his time, which Davis had labeled "thick." Modal composition, with its reliance on scales and modes, represented, as Davis called it,[2] "a return to melody."[10] In a 1958 interview with Nat Hentoff of The Jazz Review, Davis elaborated on this form of composition in contrast to the chord progression predominant in bebop, stating "No chords ... gives you a lot more freedom and space to hear things. When you go this way, you can go on forever. You don't have to worry about changes and you can do more with the [melody] line. It becomes a challenge to see how melodically innovative you can be. When you're based on chords, you know at the end of 32 bars that the chords have run out and there's nothing to do but repeat what you've just done—with variations. I think a movement in jazz is beginning away from the conventional string of chords... there will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them."[2]

As noted by Bill Evans in the LP liner notes, "Miles conceived these settings only hours before the recording dates."[8] Evans continued with an introduction concerning the modes used in each composition on the album. "So What" consists of two modes: sixteen measures of the first, followed by eight measures of the second, and then eight again of the first.[8] "Freddie Freeloader" is a standard twelve-bar blues form. "Blue in Green" consists of a ten-measure cycle following a short four-measure introduction.[8] "All Blues" is a twelve-bar blues form in 6/8 time. "Flamenco Sketches" consists of five scales, which are each played "as long as the soloist wishes until he has completed the series".[8]

Liner notes list Davis as writer of all compositions, but many scholars and fans believe that Bill Evans wrote part or the whole of "Blue in Green" and "Flamenco Sketches".[11] Bill Evans assumed co-credit with Davis for "Blue in Green" when recording it on his Portrait in Jazz album. The Davis estate acknowledged Evans' authorship in 2002.[12] The practice of a band leader's appropriating authorship of a song written by a sideman occurred frequently in the jazz world, as legendary saxophonist Charlie Parker did so to Davis when Parker took a songwriting credit for the tune "Donna Lee", written by Davis while employed as a sideman in Charlie Parker's quintet in the late 1940s.[13] The composition later became a popular jazz standard. Another example is the introduction to "So What", attributed to Gil Evans, which is closely based on the opening measures of French composer Claude Debussy's Voiles (1910), the second prelude from his first collection of preludes.[14]

Reception and legacy

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Retrospective reviews | |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A+[17] |

| MusicHound Jazz | 5/5[16] |

| The Penguin Guide to Jazz | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[19] |

| PopMatters | 10/10[20] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Sputnikmusic | 5/5[23] |

Since its release in 1959, Kind of Blue has been regarded by many critics as Davis's greatest work; it is his most acclaimed album, and has been cited as the best-selling jazz record released,[24][25] despite later claims attributing the achievement to Davis's first official gold record Bitches Brew (1970).[26][27][28] Music writer Chris Morris cited Kind of Blue as "the distillation of Davis's art."[29] Kind of Blue has also been noted as one of the most influential albums in the history of jazz. One reviewer has called it a "defining moment of twentieth century music."[30] Several of the songs from the album have become jazz standards. Kind of Blue is consistently ranked among the greatest albums of all time.[31] In a review of the album, AllMusic senior editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine stated:

Kind of Blue isn't merely an artistic highlight for Miles Davis, it's an album that towers above its peers, a record generally considered as the definitive jazz album, a universally acknowledged standard of excellence. Why does Kind of Blue possess such a mystique? Perhaps because this music never flaunts its genius.... It's the pinnacle of modal jazz — tonality and solos build from the overall key, not chord changes, giving the music a subtly shifting quality.... It may be a stretch to say that if you don't like Kind of Blue, you don't like jazz — but it's hard to imagine it as anything other than a cornerstone of any jazz collection.[15]

In 1958, however, the arrival of Ornette Coleman on the jazz scene via his fall residency at the Five Spot club, consolidated by the release of his The Shape of Jazz to Come LP in 1959, muted the initial impact of Kind of Blue, a happenstance that irritated Davis greatly.[32] Though Davis and Coleman both offered alternatives to the rigid rules of bebop, Davis would never reconcile himself to Coleman's free jazz innovations, although he would incorporate musicians amenable to Coleman's ideas with his great quintet of the mid-1960s, and offer his own version of "free" playing with his jazz fusion outfits in the 1970s.[33] The influence of Kind of Blue did build, and all of the sidemen from the album went on to achieve success on their own. Evans formed his influential jazz trio with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian; "Cannonball" Adderley fronted popular bands with his brother Nat; Kelly, Chambers and Cobb continued as a touring unit, recording under Kelly's name as well as in support of Coltrane and Wes Montgomery, among others; and Coltrane went on to become one of the most revered and innovative of all jazz musicians. Even more than Davis, Coltrane took the modal approach and ran with it during his career as a leader in the 1960s, leavening his music with Coleman's ideas as the decade progressed.[34]

According to Acclaimed Music, Kind of Blue is the 49th most ranked record on critics' all-time lists.[35] In 1994, the album was ranked number one in Colin Larkin's Top 100 Jazz Albums. Larkin described it as "the greatest jazz album in the world".[36] It has been ranked at or near the top of numerous "best album" lists in disparate genres.[37][38][39][40] In 2002, Kind of Blue was one of 50 recordings chosen that year by the Library of Congress to be added to the National Recording Registry.[41] In selecting the album as number 12 on its 2003 list of the 500 greatest albums of all time, Rolling Stone magazine stated: "This painterly masterpiece is one of the most important, influential and popular albums in jazz".[42] On December 16, 2009, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution honoring the 50th anniversary of Kind of Blue and "reaffirming jazz as a national treasure".[43] It is included in the 2005 book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die, described by reviewer Seth Jacobson as "a genre-defining moment in twentieth-century music, period."[44]

Influence

The album's influence has reached beyond jazz, as musicians of such genres as rock and classical have been influenced by it, while critics have written about it as one of the most influential albums of all time.[45][46] Many improvisatory rock musicians of the 1960s referred to Kind of Blue for inspiration, along with other Davis albums, as well as Coltrane's modal records My Favorite Things (1961) and A Love Supreme (1965). Guitarist Duane Allman of the Allman Brothers Band said his soloing on songs such as "In Memory of Elizabeth Reed" "comes from Miles and Coltrane, and particularly Kind of Blue. I've listened to that album so many times that for the past couple of years, I haven't hardly listened to anything else."[47] Pink Floyd keyboardist Richard Wright said that the chord progressions on the album influenced the structure of the introductory chords to the song "Breathe" on their landmark opus The Dark Side of the Moon (1973).[48] In his book Kind of Blue: The Making of a Miles Davis Masterpiece, writer Ashley Kahn wrote "still acknowledged as the height of hip, four decades after it was recorded, Kind of Blue is the premier album of its era, jazz or otherwise. Its vapory piano introduction is universally recognized".[49] Producer Quincy Jones, one of Davis' longtime friends, wrote: "That [Kind of Blue] will always be my music, man. I play Kind of Blue every day—it's my orange juice. It still sounds like it was made yesterday".[49] Pianist Chick Corea, one of Miles' acolytes, was also struck by its majesty, later stating "It's one thing to just play a tune, or play a program of music, but it's another thing to practically create a new language of music, which is what Kind of Blue did."[50]

Gary Burton noted the consistent innovation present throughout the album, stating: "It wasn’t just one tune that was a breakthrough, it was the whole record. When new jazz styles come along, the first few attempts to do it are usually kind of shaky. Early Charlie Parker records were like this. But with Kind of Blue [the sextet] all sound like they’re fully into it."[51] Along with the Dave Brubeck Quartet's Time Out (1959) and Coltrane's Giant Steps (1960), Kind of Blue has often been recommended by music writers as an introductory jazz album, for similar reasons: the music on both records is very melodic, and the relaxed quality of the songs makes the improvisation easy for listeners to follow, without sacrificing artistry or experimentation.[52] Upon the release of the 50th anniversary collector's edition of the album, a columnist for All About Jazz stated "Kind of Blue heralded the arrival of a revolutionary new American music, a post-bebop modal jazz structured around simple scales and melodic improvisation. Trumpeter/band leader/composer Miles Davis assembled a sextet of legendary players to create a sublime atmospheric masterpiece. Fifty years after its release, Kind of Blue continues to transport listeners to a realm all its own while inspiring musicians to create to new sounds—from acoustic jazz to post-modern ambient—in every genre imaginable."[53] Later in an interview, renowned hip-hop artist and rapper Q-Tip reaffirmed the album's reputation and influence when discussing the significance of Kind of Blue, stating "It's like the Bible—you just have one in your house."[54] The 2014 album Blue by Mostly Other People Do the Killing is a note-for-note reproduction of Kind of Blue.[55]

The Kind of Blue musicians appeared together in further recorded ventures through the 1960s. Davis had made a rare post-1953 sideman appearance in 1958 on Adderley's Somethin' Else album; Evans and Adderley collaborated on the latter's LP Know What I Mean? from 1961. Kelly and Chambers backed Hank Mobley on Soul Station in 1960, and Evans and Chambers played on the sessions for The Blues and the Abstract Truth by Oliver Nelson in 1961. The rhythm section of Kelly, Chambers, and Cobb backed Coltrane for Coltrane Jazz and one track on his landmark Giant Steps, which featured Chambers throughout. That trio stayed with Davis for the recordings Someday My Prince Will Come and the live sets at the Blackhawk and at Carnegie Hall.

Davis in retrospect

Late in his life, from the electric period on, Davis repeatedly disregarded his earlier work, such as the music of Birth of the Cool or Kind of Blue. In Davis' view, remaining static stylistically was the wrong option.[56]

"So What" or Kind of Blue, they were done in that era, the right hour, the right day, and it happened. It's over [...]. What I used to play with Bill Evans, all those different modes, and substitute chords, we had the energy then and we liked it. But I have no feel for it anymore—it's more like warmed-over turkey.

When Shirley Horn insisted, in 1990, that Davis reconsider playing the gentle ballads and modal tunes of his Kind of Blue period, he demurred: "Nah, it hurts my lip."[58]

Release history

Kind of Blue was originally released as a 12-inch vinyl record, in both stereo and mono. There have been several reissues of Kind of Blue, including additional printings throughout the vinyl era. On some editions, the label switched the order for the two tracks on side two, "All Blues" and "Flamenco Sketches". The record has been remastered many times during the compact disc era, including the 1986 Columbia Jazz Masterpieces reissue and,[59] most notably, the 1992 remastering that corrected the speed for side one, which had been issued slightly off-pitch originally,[60] and the 1997 issue that added the alternative take of "Flamenco Sketches".[59] In 2005, a DualDisc release included the original album, a digital remastering in 5.1 Surround Sound and LPCM Stereo, and a 25-minute documentary Made in Heaven about the making and influence of Kind of Blue.[61] Kind of Blue has also been re-released on a rare 24-carat gold CD collectors version.[59]

The album was also released on many other formats, many of which are only to be found second hand.

- Two-track open-reel tape (US only), Columbia GCB 60, from which "Freddie Freeloader" and "Flamenco Sketches" were omitted to keep cost down. This release was on the market less than a year and was discontinued some time after July 1961, after Sketches of Spain had been released as four-track only. Sonically most often better than the four-track counterpart that replaced it. The reports that the two-track version was the only one to be issued at correct speed for the tracks off the first album side are false.[62] None issued were at the correct speed.[63]

- Four-track open-reel tape (US only), Columbia CQ 379, as the complete five-track album. This release replaced the two-track release and remained in the Columbia catalog for a few years. Some tracks are available on other reel tapes issued current at the time of or following the original release of the album, as by Various Artists. None issued were at the correct speed.[63] "All Blues" is included on the Greatest Hits album.[62]

- Armed Forces Radio and Television Service 16-inch transcription discs. Note these are monophonic and the tune on side P-6925 marked "Flamenco Sketches" actually holds "All Blues".[64] None issued were at the correct speed.[63]

- Philips Compact Cassette. Both as the original album prior to the Jazz Masterpiece remaster, and as the 1987 Jazz Masterpiece remaster. Neither are at the correct speed.[63]

- MiniDisc, Columbia CM 40579 (US). Only as the master prior to 1997, but not as the Jazz Masterpiece remaster. This was unavailable by the end of the 1990s when production of Jazz Masterpiece series had ceased. None issued were at the correct speed.[63]

- Two-disc box set "50th Anniversary Collector's Edition", released on September 30, 2008, by Columbia and Legacy.[65]

Track listing

| Side one | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 1. | "So What" | Miles Davis | 9:04 |

| 2. | "Freddie Freeloader" | Miles Davis | 9:34 |

| 3. | "Blue in Green" | Miles Davis, Bill Evans | 5:27 |

| Side two | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 4. | "All Blues" | Miles Davis | 11:33 |

| 5. | "Flamenco Sketches" | Miles Davis, Bill Evans | 9:26 |

| 1997 reissue bonus track | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 6. | "Flamenco Sketches" (alternate take) | Miles Davis, Bill Evans | 9:32 |

| 2008 bonus tracks | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 7. | "Freddie Freeloader" (studio sequence 1) | 0:53 |

| 8. | "Freddie Freeloader" (false start) | 1:27 |

| 9. | "Freddie Freeloader" (studio sequence 2) | 1:30 |

| 10. | "So What" (studio sequence 1) | 1:55 |

| 11. | "So What" (studio sequence 2) | 0:13 |

| 12. | "Blue in Green" (studio sequence) | 1:58 |

| 13. | "Flamenco Sketches" (studio sequence 1) | 0:45 |

| 14. | "Flamenco Sketches" (studio sequence 2) | 1:12 |

| 15. | "All Blues" (studio sequence) | 0:18 |

| 2008 bonus disc | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 1. | "On Green Dolphin Street" | Bronislaw Kaper , Ned Washington | 9:50 |

| 2. | "Fran-Dance" | Miles Davis | 5:49 |

| 3. | "Stella by Starlight" | Victor Young, Ned Washington | 4:46 |

| 4. | "Love for Sale" | Cole Porter | 11:49 |

| 5. | "Fran-Dance" (alternate take) | Miles Davis | 5:53 |

| 6. | "So What" (recorded at Kurhaus, The Hague, April 9, 1960) | Miles Davis | 17:29 |

Personnel

Musicians

Per the liner notes.

- Miles Davis – trumpet

- Julian "Cannonball" Adderley – alto saxophone (except on "Blue in Green")

- John Coltrane – tenor saxophone

- Bill Evans – piano (except on "Freddie Freeloader")

- Wynton Kelly – piano (on "Freddie Freeloader")

- Paul Chambers – double bass

- Jimmy Cobb – drums

Production

- Irving Townsend – producer

- Fred Plaut – engineering

- Don Hunstein – photography

- Bill Evans – original liner notes

- Michael Cuscuna – reissue production

- Mark Wilder – remix engineering

- Jay Maisel – 2009 reissue booklet photography

- Nat Hentoff – 1997 reissue liner notes

- Francis Davis – 2009 reissue liner notes

Chart positions

Billboard Music Charts (North America)

| Year | Chart | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1977 | Jazz Albums | 37 |

| 1987 | Top Jazz Albums | 10 |

| 2001 | Top Internet Albums | 14 |

| 2015 | Vinyl Albums[66] | 3 |

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/Sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[67] | Platinum | 70,000^ |

| Belgium (BEA)[68] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Italy (FIMI)[69] | Platinum | 100,000* |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[70] | 2× Platinum | 600,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[71] | 4× Platinum | 4,000,000^ |

|

*sales figures based on certification alone | ||

References

- ↑ Kahn, pp. 86–87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ashley Kahn (2001). Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece. foreword by Jimmy Cobb. Da Capo Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-306-81067-0.

- ↑ Russell, George. Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization. New York: Russ-Hix Music Pub. Co.

Library of Congress Catalog Record available at lccn.loc.gov/unk84111092.

Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization website located at www.lydianchromaticconcept.com.

Author George Russell’s website located at www.georgerussell.com - ↑ "George Russell — About George". Concept Publishing. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- 1 2 "Liner note reprint: Miles Davis — Kind of Blue (FLAC — Master Sound — Super Bit Mapping)". Stupid and Contagious. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ↑ Ashley Kahn (2001). Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece. foreword by Jimmy Cobb. Da Capo Press, USA. p. 83. ISBN 0-306-81067-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Khan, Ashley. Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece. New York: Da Capo Press, 2000; p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Palmer (1997), pp. 4–7.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Bob. Liner Notes, Miles Davis at Newport 1958; Columbia/Legacy CK85202, 2001, p. 4.

- 1 2 Palmer, Robert (1997). "Liner Notes to 1997 Reissue". Kind of Blue (CD). New York, NY: Sony Music Entertainment, Inc./Columbia Records.

- ↑ Kahn, p. 299a.

- ↑ Kahn, p. 299b.

- ↑ Miles Davis with Quincy Troupe, Miles: The Autobiography, Simon and Schuster, 2001, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Kahn, p. 178.

- 1 2 Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Review: Kind of Blue. AllMusic. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- 1 2 "Kind of Blue". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ↑ Sandow, Greg. Review: Kind of Blue. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ Cook, Richard. "Review: Kind of Blue". Penguin Guide to Jazz: 376. September 2002.

- ↑ Schreiber, Ryan. Review: Kind of Blue. Pitchfork Media. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ↑ Friedman, Lou. Review: Kind of Blue. PopMatters. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ Columnist. "Review: Kind of Blue". Q: 116. March 1995.

- ↑ Hoard, Christian. "Review: Kind of Blue". Rolling Stone: 214–217. November 2, 2004.

- ↑ Fisher, Tyler. Review: Kind of Blue. Sputnikmusic. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ The All-TIME 100 Albums – Kind of Blue. Time Inc. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ↑ The Dozens – Jazz.com. jazz.com. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ↑ MILES BEYOND The Making of the Bitches Brew boxed set. Paul Tingen. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ↑ Miles Electric: A Different Kind of Blue (DVD). PopMatters. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ↑ Miles Davis' Bitches Brew – ColumbiaJazz. Columbia. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ↑ Morris, Chris. Review: Kind of Blue. Yahoo! Music. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ↑ Philip B. Pape. "All About Jazz: Kind of Blue — Review". All About Jazz. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Miles Davis – Kind of Blue" (rankings, rating, etc.) Acclaimed Music. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Kahn, p. 183.

- ↑ Jazz Extra – the biography of Miles Davis. Jazz Extra. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Porter, Lewis (1999). John Coltrane: His Life and Music. University of Michigan Press. pp. 281–283. ISBN 0-472-08643-X.

- ↑ "Miles Davis". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ↑ Larkin, Colin (1994). Guinness Book of Top 1000 Albums (1 ed.). Gullane Children's Books. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-85112-786-6.

- ↑ The All-TIME 100 Albums. Time.com. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ Rateyourmusic's "Top Albums of All-Time". Rate Your Music. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Kind of Blue review notes". Tower.com. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Kind of Blue", The Library of Congress. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ "The RS 500 Greatest Albums of All Time: 12) Kind of Blue". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Jarenwattananon, Patrick. The U.S. Congress and the 'Kind of Blue' Blues. NPR. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ↑ Dimery, Robert (2009). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. Octopus Publishing Group, London. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9781844036240. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ↑ Miles Davis: Kind of Blue – NPR. NPR. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ NPR's Jazz Profiles: Miles Davis Kind of Blue. NPR. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ Palmer (1997), p. 9.

- ↑ Andy Mabbett (1995). The Complete Guide to the Music of Pink Floyd. Omnibus Press, 14/15 Berners Street, London. pp. 178–179. ISBN 0-7119-4301-X.

- 1 2 Kahn, p. 19.

- ↑ Kahn, p. 16.

- ↑ Kahn, p. 179.

- ↑ 1959: A Great Year in Jazz. All About Jazz. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Jazz News: Miles Davis – Kind of Blue: 50th Anniversary Collectors Edition Coming in September. All About Jazz. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ↑ "Kind of Blue 50th Anniversary Edition". Pitchfork. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ↑ Miles Davis’s Jazz Masterpiece ‘Kind of Blue’ Is Redone, Wall Street Journal, 10 October 2014

- ↑ Davis, Miles; Jeff Sultanof (2002). Miles Davis – Birth of the Cool Complete Score Book. US: Hal Leonard. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0634006827. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ↑ Quoted in Ashley Kahn, Miles Davis and Bill Evans: Miles and Bill in Black & White, JazzTimes, September 2001.

- ↑ Interview to Shirley Horn. After 1990. Quoted in Ashley Kahn, Miles Davis and Bill Evans: Miles and Bill in Black & White, JazzTimes, September 2001.

- 1 2 3 Discogs.com – Search: Miles Davis – Kind Of Blue. Discogs. Retrieved on August 11, 2008.

- ↑ The Fifth Element #34, Stereophile, February 2006, retrieved September 1, 2010

- ↑ Kind Of Blue (Dual Disc), Sony, 2005.

- 1 2 From Columbia tape catalogs at the time

- 1 2 3 4 5 Speed issues are explained in the booklet with the post-1997 remaster: the same speed master was used in all cases.

- ↑ From two 16-inch AFRTS records this contributor owns, won on eBay.

- ↑ "Kind of Blue 50th Anniversary Collector's Edition". All Music. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Miles Davis - Chart history | Billboard". www.billboard.com. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ↑ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2003 Albums". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – 2003". Ultratop & Hung Medien / hitparade.ch. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ↑ "Italian album certifications – Miles Davis – Kind of Blue" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved February 7, 2015. Select Album e Compilation in the field Sezione. Enter Miles Davis in the field Filtra. The certification will load automatically

- ↑ "British album certifications – Miles Davis – Kind of Blue". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved January 5, 2014. Enter Kind of Blue in the field Keywords. Select Title in the field Search by. Select album in the field By Format. Select Platinum in the field By Award. Click Search

- ↑ "American album certifications – Miles Davis – Kind of Blue". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved September 19, 2008. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH

Bibliography

- Blumenthal, Bob (2001). "Liner Notes". Miles Davis at Newport 1958. Columbia/Legacy CK85202.

- Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. Completely Revised and Updated 4th Edition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Cook, Richard; Morton, Brian (2002). The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD. 6th edition. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051521-6.

- Kahn, Ashley (2001). Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece. foreword by Cobb, Jimmy, Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81067-0.

- Palmer, Robert (1997). "Liner Notes to 1997 Reissue". Kind of Blue (CD). New York, NY: Sony Music Entertainment, Inc./Columbia Records.

External links

- Miles Davis: 'Kind of Blue' program in National Public Radio's Jazz Profiles series

- Kind of Blue at MILESTONES: A Miles Davis Collector's Site