Kid Icarus

| Kid Icarus | |

|---|---|

North American cover art | |

| Developer(s) | TOSE |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Satoru Okada |

| Producer(s) | Gunpei Yokoi |

| Designer(s) |

Toru Osawa Yoshio Sakamoto |

| Composer(s) | Hirokazu Tanaka |

| Series | Kid Icarus |

| Platform(s) | Family Computer Disk System, Nintendo Entertainment System, Game Boy Advance, Nintendo 3DS |

| Release date(s) | |

| Genre(s) | Action, platforming |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Kid Icarus[lower-alpha 1] is an action platform video game for the Family Computer Disk System in Japan and the Nintendo Entertainment System in Europe and North America. The first entry in Nintendo's Kid Icarus series, it was published in Japan in December 1986, and in Europe and North America in February and July 1987, respectively. It was later re-released for the Game Boy Advance in Japan during 2004, and for the Wii's Virtual Console online service in 2007. A sequel to this game was released for the Game Boy in 1991, and a third entry to the series was published for the Nintendo 3DS handheld console in March 2012.

The plot of Kid Icarus revolves around protagonist Pit's quest for three sacred treasures, which he must equip to rescue the Grecian fantasy world Angel Land and its ruler, the goddess Palutena. The player controls Pit through platform areas while fighting monsters and collecting items. Their objective is to reach the end of the levels, and to find and defeat boss monsters that guard the three treasures. The game was developed by Nintendo's Research and Development 1 division, and co-developed with TOSE, who helped with additional programming.[2] It was designed by Toru Osawa and Yoshio Sakamoto, directed by Satoru Okada, and produced by Gunpei Yokoi.

Despite its mixed critical reception, Kid Icarus is a cult classic.[3][4][5] Reviewers praised the game for its music and its mixture of gameplay elements from different genres, but criticized its graphics and high difficulty level. It was included in several lists of the best games compiled by IGN and Nintendo Power. After the release of the Game Boy sequel Kid Icarus: Of Myths and Monsters in 1991, the game series lay dormant for 21 years. It was eventually revived with a 3D shooter for the Nintendo 3DS, titled Kid Icarus: Uprising, after Pit's inclusion as a playable character in Super Smash Bros. Brawl.

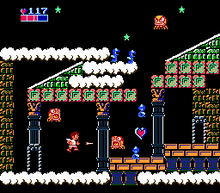

Gameplay

Kid Icarus is an action platformer with role-playing elements.[6] The player controls the protagonist Pit through two-dimensional levels, which contain monsters, obstacles and items.[7][8] Pit's primary weapon is a bow with an unlimited supply of arrows that can be upgraded with three collectable power items: the guard crystal shields Pit from enemies, the flaming arrows hit multiple targets, and the holy bow increases the range of the arrows.[8][9][10] These upgrades will work only if Pit's health is high enough.[11] The game keeps track of the player's score, and increases Pit's health bar at the end of a level if enough points were collected.[11][12]

Throughout the stages, the player may enter doors to access seven different types of chambers. Stores and black markets offer items in exchange for hearts, which are left behind by defeated monsters. Treasure chambers contain items, enemy nests give the player an opportunity to earn extra hearts, and hot springs restore Pit's health.[8][9][13] In the god's chamber, the strength of Pit's bow and arrow may be increased depending on several factors, such as the number of enemies defeated and the amount of damage taken in battle.[9][11][13] In the training chamber, Pit will be awarded with one of the three power items if he passes a test of endurance.[8][9]

The game world is divided into three stages – the underworld, the over world (Earth) and the sky world.[14] Each stage encompasses three unidirectional area levels and a fortress.[14][15][16] The areas of the underworld and sky world stages have Pit climb to the top, while those of the surface world are side-scrolling levels. The fortresses at the end of the stages are labyrinths with non-scrolling rooms, in which the player must find and defeat a gatekeeper boss.[8] Within a fortress, Pit may buy a check sheet, pencil and torch to guide him through the labyrinth.[9] A single-use item, the hammer, can destroy stone statues, which frees a flying soldier called a Centurion that will aid the player in boss battles.[9][17] For each of the bosses destroyed, Pit receives one of three sacred treasures that are needed to access the fourth and final stage, the sky temple.[8] This last portion abandons the platforming elements of the previous levels, and resembles a scrolling shooter.[8][18]

Plot

The game is set in Angel Land, which is a fantasy world with a Greek mythology theme.[18][19] The backstory of Kid Icarus is described in the instruction booklet: before the events of the game, Earth was ruled by Palutena: Goddess of Light and Medusa: Goddess of Darkness. Palutena bestowed the people with light to make them happy. Medusa hated the humans, dried up their crop, and turned them to stone. Enraged by this, Palutena transformed Medusa into a monster and banished her to the Underworld. Out of revenge, Medusa conspired with the monsters of the Underworld to take over Palutena's residence the Palace in the Sky.[19] She launched a surprise attack, and stole the three sacred treasures — the Mirror Shield, the Light Arrows and the Wings of Pegasus — which deprived Palutena's army of its power. After her soldiers had been turned to stone by Medusa, Palutena was defeated in battle and imprisoned deep inside the Palace in the Sky.

With her last power, she sent a bow and arrow to the young angel Pit. He escapes from his prison in the Underworld and sets out to save Palutena and Angel Land.[19][20] Throughout the course of the story, Pit retrieves the three sacred treasures from the fortress gatekeepers at their respectful fortresses in the Underworld, the Overworld, and the Skyworld.[14] Afterward, he equips himself with the treasures and storms the sky temple where he defeats Medusa and rescues Palutena.[8] The game has multiple endings: depending on the player's performance, Palutena either presents Pit with headgear, or transforms him into a full-grown angel.[8][11][21]

Development and releases

_cropped.jpg)

This game was designed at Nintendo's Research and Development 1 (R&D1) division, while the programming was handled by the external company Intelligent Systems (known as Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena at the time). The game was developed for the Family Computer Disk System (FDS) because the peripheral's Disk Card media allowed for three times the storage capacity of the Family Computer's (and NES's) console's cartridges. Combined with the possibility to store the players' progress, the floppy disk format enabled the developers to create a longer game with a more extensive game world. Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena was Toru Osawa's debut as a video game designer, and he was the only staff member working on the game at the beginning of the project.[18] Osawa (credited in the U.S. version as Inusawa) intended to make Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena an action game with role-playing elements, and wrote a story rooted in Greek mythology, which he had always been fond of.[18][22] He drew the pixel art, and wrote the technical specifications, which were the basis for the playable prototype that was programmed by Intelligent Systems. After Nintendo's action-adventure Metroid had been finished, more staff members were allotted to the development of Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena.[18]

The game was directed by Satoru Okada (credited as S. Okada), and produced by the general manager of the R&D1 division, Gunpei Yokoi (credited as G. Yokoi). Hirokazu Tanaka (credited as Hip Tanaka) composed the music for Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena.[18][22] Yoshio Sakamoto (credited as Shikao.S) joined the team as soon as he had returned from his vacation after the completion of Metroid. He streamlined the development process, and made many decisions that affected the game design of Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena. Several out-of-place elements were included in the game, such as credit cards, a wizard turning player character Pit into an eggplant, and a large, moving nose that was meant to resemble composer Tanaka. Sakamoto attributed this unrestrained humor to the former personnel of the R&D1 division, which he referred to as "strange". Osawa said that he had originally tried to make Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena completely serious, but opted for a more humorous approach after objections from the team.[18]

To meet the game's projected release date of December 19, 1986, the staff members worked overtime and often stayed in the office at night. They used torn cardboard boxes as beds, and covered themselves in curtains to resist the low temperatures of the unheated development building. Eventually, Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena was finished and entered production a mere three days before the release date. Several ideas for additional stages had to be dropped because of these scheduling conflicts.[18] In February and July 1987, respectively, a cartridge-based version was published for the NES in Europe and North America under the name Kid Icarus.[23] For this release, the graphics of the ending were updated, and staff credits were added to the game.[18] Unlike Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena, which saves the player's progress on the Disk Card, Kid Icarus uses a password system to return to a game after the console was turned off.[24][25] In August 2004, Myth of Light: The Mirror of Palutena was re-released as part of the Famicom Mini Disk System Selection for the Game Boy Advance.[26] The game was published internationally for the Wii's Virtual Console in 2007. The North American, European and Australian versions of this digital release have the cheat codes of the NES version removed.[27]

3D Classics

A 3D Classics remake of Kid Icarus was published for the Nintendo 3DS handheld console. The remake features stereoscopic 3D along with updated graphics including backgrounds, which the original lacked. It also uses the same save system as the Family Computer Disk System version does, as opposed to the Password system from the NES version. The 3D Classics version also utilizes the Family Computer Disk System's music and sound effects (utilizing the extra sound channel not available in the NES version).

The game became available for purchase on the eShop on January 18, 2012 in Japan, on February 2, 2012 in Europe, on April 12, 2012 in Australia and on April 19, 2012 in North America. The game was available early for free via download code to users who registered two selected 3DS games with Nintendo in Japan, Europe and Australia: in Japan, it was available to users who registered any two Nintendo 3DS titles on Club Nintendo between October 1, 2011 and January 15, 2012 with the game available for download starting December 19, 2011;[28] in Europe, it was available to users who registered any two of a selection of Nintendo 3DS titles on Club Nintendo between November 1, 2011 and January 31, 2012,[29] with the first batch of emails with codes being sent out on January 5, 2012;[30] in Australia, it was available to users who registered any two of a selection of Nintendo 3DS titles on Club Nintendo between November 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012,[31] with the first batch of emails with codes being sent out in January 2012. In North America, download codes for the 3D Classics version were given to customers who pre-ordered Kid Icarus: Uprising at select retailers when they picked up the game itself,[32] which released on March 23, 2012,[33] allowing them to obtain the game before its release for purchase.

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

Kid Icarus had shipped 1.76 million copies worldwide by late 2003, and has gained a cult following.[15][35] Game Informer ranked it the 83rd best game ever made in 2001. They claimed that despite its high level of difficulty and frustration, it was fun enough to be worth playing.[36] The game has been met with mixed reviews from critics over the years. In October 1992, a staff writer of the UK publication Nintendo Magazine System said that Kid Icarus was "pretty good fun", but did not "compare too well" to other platform games, owing in part to its "rather dated" graphics.[34] Retro Gamer magazine's Stuart Hunt called Kid Icarus an "unsung hero of the NES" that "looks and sounds pretty". He described the music by Hirokazu Tanaka as "sublime", and the enemy characters as "brilliantly drawn". Although he considered the blend of gameplay elements from different genres a success, he said that Kid Icarus suffered from "frustrating" design flaws, such as its high difficulty level.[37] Jeremy Parish of 1UP.com expressed his disagreement with the game's status as an "unfairly forgotten masterpiece" among its substantial Internet following. He found Kid Icarus to be "underwhelming", "buggy" and "pretty annoying", and noted that it exhibited "shrill music[, ...] loose controls and some weird design decisions". Notwithstanding his disapproval of these elements, Parish said that the game was "[not] terrible, or even bad – just a little lacking." He recommended players to buy the Virtual Console version, if only because it allowed them to experience Kid Icarus "with a fresh perspective".[38]

GameSpot's Frank Provo reviewed the Virtual Console version of the game. He noted that the gameplay of Kid Icarus was "[not] the most unique blueprint for a video game", but that it had been "fairly fresh back in 1987". He considered the difficulty level "excessive", and found certain areas to be designed "solely to frustrate players". Provo said that the presentation of the game had "[not] aged gracefully". Despite his favorable comments on the Grecian scenery, he criticized the graphics for its small, bicolored and barely animated sprites, its black backgrounds, and the absence of multiple scrolling layers. He thought that the music was "nicely composed", but that the sound effects were "all taps and thuds". He was dissatisfied with the emulation of the game, as the Virtual Console release preserves the slowdown problems of the original NES version, but has its cheat codes removed. Provo closed his review with a warning for potential buyers: he said that players could appreciate Kid Icarus for its "straightforward gameplay and challenging level layouts", but might "find nothing special in the gameplay and recoil in horror at the unflinching difficulty."[7] Lucas M. Thomas of IGN noted that the game design was "odd" and "not Nintendo's most focused". He thought that it had "[not] aged in as timeless a manner as many other first-party Nintendo games from the NES era," and described Kid Icarus as "one of those games that made a lot more sense back in the '80s, accompanied by a tips and tricks strategy sheet." He complimented the theme music, which he considered "heroic and memorable".[15] In his review of the Virtual Console release, Thomas frowned upon Nintendo's decision to remove the NES cheat codes, and called the omission "nonsensical". He found it to be "not an issue worthy of a prolonged rant", but said that "[Nintendo has] willfully edited its product, and damaged its nostalgic value in the process".[27]

Kid Icarus was included in IGN's lists of the top 100 NES games and the top 100 games of all time; it came in 20th and 84th place, respectively.[6][39] The game was inducted into GameSpy's "Hall of Fame", and was voted 54th place in Nintendo Power's top 200 Nintendo games.[8][40] Nintendo Power also listed it as the 20th best NES video game, and praised it for its "unique vertically scrolling stages, fun platforming, and infectious 8-bit tunes", in spite of its "unmerciful difficulty".[41]

Sequels

A Game Boy sequel to Kid Icarus, titled Kid Icarus: Of Myths and Monsters, was released in North America in November 1991, and in Europe on May 21, 1992.[42][43] It was developed by Nintendo in cooperation with the independent company Tose, and largely adopts the gameplay mechanics of its predecessor.[44][45] Kid Icarus: Of Myths and Monsters remained the last installment in the series for over 20 years.[46]

Pit is a recurring character in the American animated television series Captain N: The Game Master, albeit has been erroneously named as "Kid Icarus", and made cameo appearances in Nintendo games such as Tetris, F-1 Race and Super Smash Bros. Melee.[47][48] He became a playable character in the fighting game Super Smash Bros. Brawl, for which his appearance was redesigned.[49][50]

In 2008, there were rumors of a three-dimensional Kid Icarus game for the Wii that was allegedly developed by the German American studio Factor 5.[49] However, the title was said to be in production without the approval of Nintendo, and Factor 5 cancelled multiple projects following the closure of its American branch in early 2009.[51][52][53] In a 2010 interview, Yoshio Sakamoto was asked about a Kid Icarus game for the Wii, to which he replied that he was not aware of any plans to revive the franchise.[54] A new series entry for the Nintendo 3DS, Kid Icarus: Uprising, was eventually revealed at the E3 2010 trade show and was released in 2012.[55] The game is a 3D shooter, and was developed by Project Sora, the company of Super Smash Bros. designer Masahiro Sakurai.[56]

In May 2011,[57] independent development studio Flip Industries released Super Kid Icarus, an unofficial Flash game. Super Kid Icarus is noted for having a SNES style look and including cheats to reduce the difficulty.[58]

Notes

References

- ↑ Famicom 20th Anniversary Original Sound Tracks Vol. 1 (Media notes). Scitron Digital Contents Inc. 2004. SCDC-00317.

- ↑ http://gdri.smspower.org/wiki/index.php/Tose

- ↑ "'Kid Icarus: Uprising' Shows What the 3DS Can Really Do. Finally.". METR. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Kid Icarus Of Myths and Monsters". Cult of Games. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Kid Icarus Review". IGN. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- 1 2 Buchanan, Levi (October 2009). "Top 100 NES Games – 20. Kid Icarus". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Provo, Frank (February 16, 2007). "Kid Icarus Wii Review". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cassidy, William (September 14, 2003). "Hall of Fame: Kid Icarus". GameSpy. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Items That Will Make Pit a More Powerful Angel". Kid Icarus Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. July 1987. pp. 21–30.

- ↑ "VC 光神話 パルテナの鏡 – アイテム紹介" (in Japanese). Nintendo Co., Ltd. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Questions and Answers". Kid Icarus Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. July 1987. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ "Basic Wisdom". Kid Icarus Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. July 1987. pp. 11–15.

- 1 2 "VC 光神話 パルテナの鏡 – 部屋紹介" (in Japanese). Nintendo Co., Ltd. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "A Guide to Angel Land". Kid Icarus Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. July 1987. pp. 16–20.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas, Lucas M. (March 6, 2007). "Kid Icarus Review". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ↑ Kalata, Kurt. "Classic Review Archive – Kid Icarus". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Introducing the Inhabitants in Angel Land". Kid Icarus Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. July 1987. p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 やればやるほどディスクシステムインタビュー(前編). Nintendo Dream (in Japanese). Mainichi Communications Inc. (118): 96–103. August 6, 2004.

- 1 2 3 "The Tale of Kid Icarus". Kid Icarus Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. July 1987. pp. 3–8.

- ↑ "VC 光神話 パルテナの鏡 – ストーリー" (in Japanese). Nintendo Co., Ltd. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Time Machine: Kid Icarus". ComputerAndVideoGames.com. Future Publishing Limited. December 30, 2010. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- 1 2 Nintendo Co., Ltd (July 1987). Kid Icarus. Nintendo. Scene: staff credits.

- ↑ "Kid Icarus Release". GameSpot. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- ↑ "VC 光神話 パルテナの鏡 – ゲームの進めかた" (in Japanese). Nintendo Co., Ltd. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ↑ "How to Start Playing Kid Icarus". Kid Icarus Instruction Booklet. Nintendo. July 1987. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ "ファミコンミニ – 光神話 パルテナの鏡". Nintendo Co., Ltd. July 2004. Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- 1 2 Thomas, Lucas M. (March 6, 2007). "Kid Icarus VC Review". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ↑ Gantayat, Anoop (2011-10-21). "Mario 3DS Systems: Closer Look". Andriasang. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ "3D Classics: Kid Icarus will be free in UK". Official Nintendo Magazine. 2011-12-05. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014.

- ↑ "3D Classics: Kid Icarus Free Download Codes Are Being Sent Out From Nintendo". My Nintendo News. January 5, 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Ly, Hang-Veng (January 20, 2012). "Club Nintendo Australia Offers 3D Classic: Kid Icarus For Free… with Purchase". Esperino. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Fletcher, JC (January 19, 2012). "3D Classics Kid Icarus is a pre-order bonus for Uprising". Joystiq. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Newton, James (December 14, 2011). "Kid Icarus: Uprising Out in North America on 23rd March". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- 1 2 "8-Bit NES Game Index". Nintendo Magazine System. EMAP Images Limited (1): 106. October 1992.

- ↑ 2004 CESA Games White Paper. Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association: 58–63. December 31, 2003. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Cork, Jeff (2009-11-16). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games Of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. Retrieved 2013-12-02.

- ↑ Hunt, Stuart (May 22, 2008). "Retro Revival – Kid Icarus: Almost the Pits". Retro Gamer. Imagine Publishing Ltd. (51): 88–90.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (February 15, 2007). "Retro Roundup 2/15: Kirby, Kid Icarus and Paperboy". 1UP.com. UGO Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "IGN's Top 100 Games of All Time: 81–90". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. May 2003. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2006.

- ↑ "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. Nintendo (200): 58–66. February 2006.

- ↑ "Top 20 Games For Each Nintendo System". Nintendo Power. Future Publishing Limited (231): 71. August 2008.

- ↑ "Classic System Games: Complete List" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2010. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Game Boy Pelilista" (in Finnish). Nintendo of Europe; Amo Oy. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007.

- ↑ "Interview Series 2 – 戦場よりIを込めて". Creators Station. Fellows Inc. Archived from the original on June 25, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy; Barnholt, Ray; Cifaldi, Frank; Kohler, Chris; (July 17, 2010). Retronauts Episode 96 (mp3). UGO Entertainment, Inc; Podtrac, Inc. Event occurs at 75:20. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ McWhertor, Michael (July 12, 2010). "The New Kid Icarus May Explore Another Dimension: Multiplayer". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas, Lucas M. (January 26, 2011). "You Don't Know Kid Icarus". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Reiley, Sean Patrick (June 2008). "Memorial to Captain N: Kid Icarus". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Ziff Davis Media Inc. (229): 91.

- 1 2 Casamassina, Matt (December 3, 2008). "Reboot: Kid Icarus Wii". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on May 22, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Casamassina, Matt (May 18, 2006). "Smash Bros. Profile: Pit". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Geddes, Ryan (March 30, 2011). "Life Support: Games in Danger". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Casamassina, Matt (May 14, 2009). "Factor 5 Shuts Down". IGN. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on May 17, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ "History". Factor 5 GmbH. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Crecente, Brian (March 11, 2010). "Nintendo Would "Happily" Make Kid Icarus Wii". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ Gantayat, Anoop (June 16, 2010). "Project Sora Brings Kid Icarus to 3DS". Andriasang. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ Gifford, Kevin (July 14, 2010). "More on The Making of Kid Icarus: Uprising". 1UP.com. UGO Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ Flip Industries (May 2011). "Super Kid Icarus - Reception". Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ↑ Goulter, Tom (June 23, 2012). "Fan-made Super Kid Icarus imagines Pit on SNES". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

External links