Ki Teitzei

Ki Teitzei, Ki Tetzei, Ki Tetse, Ki Thetze, Ki Tese, Ki Tetzey, or Ki Seitzei (כִּי־תֵצֵא — Hebrew for "when you go," the first words in the parashah) is the 49th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the sixth in the Book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 21:10–25:19. The parashah is made up of 5,856 Hebrew letters, 1,582 Hebrew words, and 110 verses, and can occupy about 213 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews generally read the parashah in August or September.[2] Jews also read the part of the parashah about Amalek, Deuteronomy 25:17–19, as the concluding (מפטיר, maftir) reading on Shabbat Zachor, the special Sabbath immediately before Purim, which commemorates the story of Esther and the Jewish people’s victory over Haman’s plan to kill the Jews, told in the book of Esther.[3] Esther 3:1 identifies Haman as an Agagite, and thus a descendant of Amalek. Numbers 24:7 identifies the Agagites with the Amalekites. A Midrash tells that between King Agag’s capture by Saul and his killing by Samuel, Agag fathered a child, from whom Haman in turn descended.[4]

The parashah sets out a series of miscellaneous laws, mostly governing civil and domestic life, including ordinances regarding a beautiful captive of war, inheritance among the sons of two wives, a wayward son, the corpse of an executed person, found property, coming upon another in distress, rooftop safety, prohibited mixtures, sexual offenses, membership in the congregation, camp hygiene, runaway slaves, prostitution, usury, vows, gleaning, kidnapping, repossession, prompt payment of wages, vicarious liability, flogging, treatment of domestic animals, levirate marriage, weights and measures, and remembrance of the Amalekites.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashah Ki Teitzei has two "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashah Ki Teitzei has several further subdivisions, called "closed portions" (סתומה, setumah) (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within the first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah). The long first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) spans nearly the entire parashah, except for the concluding maftir (מפטיר) reading. The short second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) coincides with maftir (מפטיר) reading. Thus the parashah is nearly one complete whole. Closed portion (סתומה, setumah) divisions divide all of the readings (עליות, aliyot), often setting apart separate laws.[5]

First reading — Deuteronomy 21:10–21

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses directed the Israelites that when they took captives in war, and an Israelite saw among the captives a beautiful woman whom he wanted to marry, the Israelite was to bring her into his house and have her trim her hair, pare her nails, discard her captive’s garb, and spend a month lamenting her parents.[6] Thereafter, the Israelite could take her as his wife.[7] But if he should find that he no longer wanted her, he had to release her outright, and not sell her as a slave.[8] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[9]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if a man had two wives, one loved and one unloved, and both bore him sons, but the unloved one bore him his firstborn son, then when he willed his property to his sons, he could not treat the son of the loved wife as firstborn in disregard of the older son of the unloved wife; rather, he was required to accept the firstborn, the son of the unloved one, and allot to him his birthright of a double portion of all that he possessed.[10] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[11]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if a couple had a wayward and defiant son, who did not obey his father or mother even after they disciplined him, then they were to bring him to the elders of his town and publicly declare their son to be disloyal, defiant, heedless, a glutton, and a drunkard.[12] The men of his town were then to stone him to death.[13] The first reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[14]

Second reading — Deuteronomy 21:22–22:7

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses instructed that if the community executed a man for a capital offense and impaled him on a stake, they were not to let his corpse remain on the stake overnight, but were to bury him the same day, for an impaled body affronted God.[15] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here with the end of the chapter.[14]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if one found another’s lost ox, sheep, donkey, garment, or any other lost thing, then the finder could not ignore it, but was required to take it back to its owner.[16] If the owner did not live near the finder or the finder did not know who the owner was, then the finder was to bring the thing home and keep it until the owner claimed it.[17] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[18]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if one came upon another’s donkey or ox fallen on the road, then one could not ignore it, but was required to help the owner to raise it.[19] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[20]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that a woman was not to put on man’s apparel, nor a man wear woman’s clothing.[21] Another closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[20]

And as the reading continues, Moses instructed that if one came upon a bird’s nest with the mother bird sitting over fledglings or eggs, then one could not take the mother together with her young, but was required to let the mother go and take only the young.[22] The second reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[23]

Third reading — Deuteronomy 22:8–23:7

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses taught that when one built a new house, one had to make a parapet for the roof, so that no one should fall from it.[24] One was not to sow a vineyard with a second kind of seed, nor use the yield of such a vineyard.[25] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[23]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that one was not to plow with an ox and a donkey together.[26] One was not to wear cloth combining wool and linen.[27] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[23]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that one was to make tassels (tzitzit) on the four corners of the garment with which one covered oneself.[28] Another closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[29]

As the reading continues, Moses instructed that if a man married a woman, cohabited with her, took an aversion to her, and falsely charged her with not having been a virgin at the time of the marriage, then the woman’s parents were to produce the cloth with evidence of the woman’s virginity before the town elders at the town gate.[30] The elders were then to have the man flogged and fine him 100 shekels of silver to be paid to the woman’s father.[31] The woman was to remain the man’s wife, and he was never to have the right to divorce her.[32] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[33]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if the elders found that woman had not been a virgin, then the woman was to be brought to the entrance of her father’s house and stoned to death by the men of her town.[34] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[33]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if a man was found lying with another man’s wife, both the man and the woman with whom he lay were to die.[35] Another closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[33]

As the reading continues, Moses instructed that if, in a city, a man lay with a virgin who was engaged to a man, then the authorities were to take the two of them to the town gate and stone them to death — the girl because she did not cry for help, and the man because he violated another man’s wife.[36] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[37]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if the man lay with the girl by force in the open country, only the man was to die, for there was no one to save her.[38] Another closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[37]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if a man seized a virgin who was not engaged and lay with her, then the man was to pay the girl’s father 50 shekels of silver, she was to become the man’s wife, and he was never to have the right to divorce her.[39] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here with the end of the chapter.[37]

As the reading continues in chapter 23, Moses instructed that no man could marry his father’s former wife.[40] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[41]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that God’s congregation could not admit into membership anyone whose testes were crushed or whose member was cut off.[42] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[41]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that God’s congregation could not admit into membership anyone misbegotten or anyone descended within ten generations from one misbegotten.[43] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[41]

And as the reading continues, Moses instructed that God’s congregation could not admit into membership any Ammonite or Moabite, or anyone descended within ten generations from an Ammonite or Moabite.[44] As long as they lived, Israelites were not to concern themselves with the welfare or benefit of Ammonites or Moabites, because they did not meet the Israelites with food and water after the Israelites left Egypt, and because they hired Balaam to curse the Israelites — but God refused to heed Balaam, turning his curse into a blessing.[45] The third reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[46]

Fourth reading — Deuteronomy 23:8–24

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses told the Israelites not to abhor the Edomites, for they were kinsman, nor Egyptians, for the Israelites were strangers in Egypt.[47] Great grandchildren of Edomites or Egyptians could be admitted into the congregation.[48] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[46]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that any Israelite rendered unclean by a nocturnal emission had to leave the Israelites military camp, bathe in water toward evening, and reenter the camp at sundown.[49] The Israelites were to designate an area outside the camp where they might relieve themselves, and to carry a spike to dig a hole and cover up their excrement.[50] As God moved about in their camp to protect them, the Israelites were to keep their camp holy.[51] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[52]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that if a slave sought refuge with the Israelites, the Israelites were not to turn the slave over to the slave’s master, but were to let the former slave live in any place the former slave might choose and not ill-treat the former slave.[53] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[52]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses forbade the Israelites to act as harlots, sodomites, or cult prostitutes, and from bringing the wages of prostitution into the house of God in fulfillment of any vow.[54] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[52]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses forbade the Israelites to charge interest on loans to their countrymen, but they could charge interest on loans to foreigners.[55] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[56]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses required the Israelites promptly to fulfill vows to God, but they incurred no guilt if they refrained from vowing.[57] The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[58]

Fifth reading — Deuteronomy 23:25–24:4

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses allowed a visiting Israelite to enter another’s vineyard and eat grapes until full, but the visitor was forbidden to put any in a vessel.[59] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[58]

As the reading continues, Moses allowed a visiting Israelite to enter another’s field of standing grain and pluck ears by hand, but the visitor was forbidden to cut the neighbor’s grain with a sickle.[60] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here with the end of the chapter.[58]

As the reading continues in chapter 24, Moses instructed that a divorced woman who remarried and then lost her second husband to divorce or death could not remarry her first husband.[61] The fifth reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[62]

Sixth reading — Deuteronomy 24:5–13

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses exempted a newlywed man from army duty for one year, so as to give happiness to his wife.[63] Israelites were forbidden to take a handmill or an upper millstone in pawn, for that would be taking someone’s livelihood.[64] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[65]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that one found to have kidnapped a fellow Israelite was to die.[66] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[65]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that in cases of a skin affection, Israelites were to do exactly as the priests instructed, remembering that God afflicted and then healed Miriam’s skin after the Israelites left Egypt.[67] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[65]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses forbade an Israelite who lent to a fellow Israelite to enter the borrower’s house to seize a pledge, and required the lender to remain outside while the borrower brought the pledge out to the lender.[68] If the borrower was needy, the lender was forbidden to sleep in the pledge, but had to return the pledge to the borrower at sundown, so that the borrower might sleep in the cloth and bless the lender before God.[69] The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[70]

Seventh reading — Deuteronomy 24:14–25:19

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses forbade the Israelites to abuse a needy and destitute laborer, whether an Israelite or a stranger, and were required to pay the laborer’s wages on the same day, before the sun set, as the laborer would depend on the wages.[71] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[72]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that parents were not to be put to death for children, nor were children to be put to death for parents; a person was to be put to death only for the person’s own crime.[73] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[74]

_-_The_Olive_Trees_(1889).jpg)

In the continuation of the reading, Moses forbade the Israelites to subvert the rights of the proselyte or the orphan, and forbade the Israelites to take a widow’s garment in pawn, remembering that they were slaves in Egypt and that God redeemed them.[75] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[74]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that when Israelites reaped the harvest in their fields and overlooked a sheaf, they were not to turn back to get it, but were to leave it to the proselyte, the orphan, and the widow.[76] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[74]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that when Israelites beat down the fruit of their olive trees or gathered the grapes of their vineyards, they were not to go over them again, but were leave what remained for the proselyte, the orphan, and the widow, remembering that they were slaves in Egypt.[77] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here with the end of the chapter.[78]

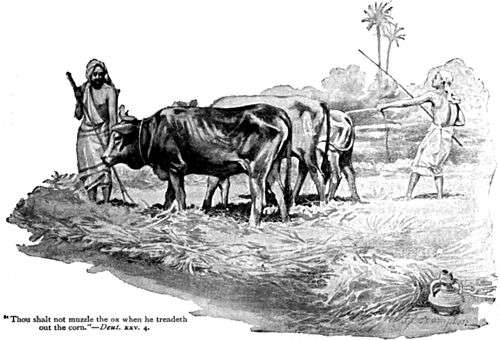

As the reading continues in chapter 25, Moses instructed that when one was to be flogged, the judge was to have the guilty one lie down and be whipped in his presence, as warranted but with no more than 40 lashes, so that the guilty one would not be degraded.[79] Israelites were forbidden to muzzle an ox while it was threshing.[80] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[81]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that when brothers dwelt together and one of them died leaving no son, the surviving brother was to marry the wife of the deceased and perform the levir’s duty, and the first son that she bore was to be accounted to the dead brother, that his name might survive.[82] But if the surviving brother did not want to marry his brother’s widow, then the widow was to appear before the elders at the town gate and declare that the brother refused to perform the levir’s duty, the elders were to talk to him, and if he insisted, the widow was to go up to him before the elders, pull the sandal off his foot, spit in his face, and declare: "Thus shall be done to the man who will not build up his brother’s house!"[83] They would then call him "the family of the unsandaled one."[84] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[85]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses instructed that if two men fought with each other, and to save her husband the wife of one seized the other man’s genitals, then her hand was to be cut off.[86] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[85]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses forbade Israelites to have alternate weights or measures, larger and smaller, and required them to have completely honest weights and measures.[87] The long first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[88]

In the maftir (מפטיר) reading of Deuteronomy 25:17–19 that concludes the parashah,[89] Moses enjoined the Israelites to remember what the Amalekites did to them on their journey, after they left Egypt, surprising them and cutting down all the stragglers at their rear.[90] The Israelites were enjoined never to forget to blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven.[91] The second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here with the end of the parashah.[92]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[93]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–2014, 2016–2017, 2019–2020 . . . | 2014–2015, 2017–2018, 2020–2021 . . . | 2015–2016, 2018–2019, 2021–2022 . . . | |

| Reading | 21:10–23:7 | 23:8–24:13 | 24:14–25:19 |

| 1 | 21:10–14 | 23:8–12 | 24:14–16 |

| 2 | 21:15–17 | 23:13–15 | 24:17–19 |

| 3 | 21:18–21 | 23:16–19 | 24:20–22 |

| 4 | 21:22–22:7 | 23:20–24 | 25:1–4 |

| 5 | 22:8–12 | 23:25–24:4 | 25:5–10 |

| 6 | 22:13–29 | 24:5–9 | 25:11–16 |

| 7 | 23:1–7 | 24:10–13 | 25:17–19 |

| Maftir | 23:4–7 | 24:10–13 | 25:17–19 |

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Deuteronomy chapter 25

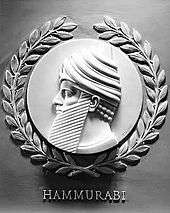

Presaging the injunction of Deuteronomy 25:13–16 for honest weights and measures, the Code of Hammurabi decreed that if merchants used a light scale to measure the grain or the silver that they lent and a heavy scale to measure the grain or the silver that they collected, then they were to forfeit their investment.[94]

In translation

While many English translations refer to "the third generation" in Deuteronomy 23:8, some versions refer to "grandchildren" (e.g. God's Word Translation, International Standard Version and The Living Bible) whereas other versions refer to "great-grandchildren" (e.g. Contemporary English Version, New Century Version and New International Reader's Version).[95]

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[96]

Deuteronomy chapters 12–26

Professor Benjamin Sommer of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America argued that Deuteronomy 12–26 borrowed whole sections from the earlier text of Exodus 21–23.[97]

Deuteronomy chapter 21

The "double portion" to be inherited by the firstborn son is literally a "double mouthful".[98] Jacob had said to Joseph in his last testament, "I give you one portion more than your brothers".[99]

The punishment of being stoned outside the city, prescribed in Deuteronomy 21:21 for a stubborn and rebellious son, was also the punishment prescribed for blaspheming the name of the Lord in Leviticus 24:16,23. The Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary suggests that "parents are considered God's representatives and invested with a portion of his authority over their children" [100] and therefore refusal to obey the voice of one's father or mother, when they have chastened one, is akin to refusal to honor the name of God. Proverbs 23:20 uses the same words, "a glutton and a drunkard", as Deuteronomy 21:20, also linked in the succeeding verses of Proverbs to the need for obedience to and respect for one's parents: "Listen to your father who begot you, and do not despise your mother when she is old" (Proverbs 23:22).

Deuteronomy chapter 22

The instruction in Exodus which parallels Deuteronomy 22:4 states that the duty to restore a fallen donkey or ox applies to one's enemy's animals as well as to one's brother's (Exodus 23:5).

Deuteronomy chapter 23

The first biblical mention of the Moabites and the Ammonites (or the people of Ammon) is in Genesis 19:37-38. It is stated there that the Ammonites were descended from Ben-Ammi, a son of Lot through incest with his younger daughter. Bén'ámmî literally means "son of my people". After the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, the daughters of Lot had sexual relations with their father, resulting in Ammon and his half brother, Moab, being conceived. This narrative was previously considered literal fact, but is now generally interpreted as recording a gross popular irony by which the Israelites expressed their loathing of the Moabites and Ammonites. [101] However, according to the same source, doubts remain as to whether the Israelites would have been willing to attribute such an irony to Lot himself. Deuteronomy 2:27-30 records the Israelites' request for safe passage and supplies through the land of the Moabites and the Moabites' refusal to "meet them with bread and water" is recalled in Deuteronomy 23:4.

Their exclusion from the Israelite congregation, "to their tenth generation, shall they not enter into the congregation of the Lord for ever",[102] is best understood to mean not only to the tenth generation, but for ever; and this law was understood as in force in Nehemiah's time, which was more than ten generations from the occupation of Canaan.[103] The text of Deuteronomy 23:4 was read in Nehemiah 13:1-2 when the post-exilic temple was rededicated.

Deuteronomy chapter 24

The Hebrew Bible reports skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara’at) and a person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora) at several places, often (and sometimes incorrectly) translated as "leprosy" and "a leper." In Exodus 4:6, to help Moses to convince others that God had sent him, God instructed Moses to put his hand into his bosom, and when he took it out, his hand was "leprous (מְצֹרַעַת, m’tzora’at), as white as snow." In Leviticus 13–14, the Torah sets out regulations for skin disease (צָרַעַת, tzara’at) and a person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora). In Numbers 12:10 after Miriam spoke against Moses, God’s cloud removed from the Tent of Meeting and "Miriam was leprous (מְצֹרַעַת, m’tzora’at), as white as snow." In the current parashah, Moses warned the Israelites in the case of skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara’at) diligently to observe all that the priests would teach them, remembering what God did to Miriam (Deuteronomy 24:8–9). In 2 Kings 5:1–19, part of the haftarah for parashah Tazria, the prophet Elisha cures Naaman, the commander of the army of the king of Aram, who was a "leper" (מְּצֹרָע, metzora). In 2 Kings 7:3–20, part of the haftarah for parashah Metzora, the story is told of four "leprous men" (מְצֹרָעִים, m’tzora’im) at the gate during the Arameans’ siege of Samaria. And in 2 Chronicles 26:19, after King Uzziah tried to burn incense in the Temple in Jerusalem, "leprosy (צָּרַעַת, tzara’at) broke forth on his forehead."

Deuteronomy 24:14–15 and 17–22 admonish the Israelites not to wrong the stranger, for “you shall remember that you were a bondman in Egypt.” (See also Exodus 22:20; 23:9; Leviticus 19:33–34; Deuteronomy 1:16; 10:17–19 and 27:19.) Similarly, in Amos 3:1, the 8th century BCE prophet Amos anchored his pronouncements in the covenant community's Exodus history, saying, “Hear this word that the Lord has spoken against you, O children of Israel, against the whole family that I brought up out of the land of Egypt.”[104]

The prophet Isaiah used the practice of leaving olives on the boughs and grapes in the vineyard for gleanings (Deuteronomy 24:20–21) as a sign of hope for Israel when he forecast the nation's downfall:

- "In that day it shall come to pass that the glory of Jacob will wane ... yet gleaning grapes will be left in it, like the shaking of an olive tree, two or three olives at the top of the uppermost bough, four or five in its most fruitful branches." (Isaiah 12:10)

Deuteronomy chapter 25

The Israelites' victory over the Amalekites and the role of Moses, supported by Aaron and Hur in directing the battle's outcome, was recorded in Exodus 17:8-16, but the Exodus narrative does not mention the Amalekites' tactics of attacking the "faint and weary" at the rear of the Israelites' convoy (Deuteronomy 25:17). At Moses' direction it was also recorded in another ancient text, possibly the Book of the Wars of the Lord, "I will utterly blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven.” (Exodus 17:14).

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[105]

Deuteronomy chapter 23

Philo read Deuteronomy 23:22 to instruct us to be prompt in our gratitude to God. Philo cited Cain as an example of a "self-loving man" who (in Genesis 4:3) showed his gratitude to God too slowly. Philo taught that we should hurry to please God without delay. Thus Deuteronomy 23:22 enjoins, "If you vow a vow, you shall not delay to perform it." Philo explained that a vow is a request to God for good things, and Deuteronomy 23:22 thus enjoins that when one has received them, one must offer gratitude to God as soon as possible. Philo divided those who fail to do so into three types: (1) those who forget the benefits that they have received, (2) those who from an excessive conceit look upon themselves and not God as the authors of what they receive, and (3) those who realize that God caused what they received, but still say that they deserved it, because they are worthy to receive God’s favor. Philo taught that Scripture opposes all three. Philo taught that Deuteronomy 8:12–14 replies to the first group who forget, "Take care, lest when you have eaten and are filled, and when you have built fine houses and inhabited them, and when your flocks and your herds have increased, and when your silver and gold, and all that you possess is multiplied, you be lifted up in your heart, and forget the Lord your God." Philo taught that one does not forget God when one remembers one’s own nothingness and God’s exceeding greatness. Philo interpreted Deuteronomy 8:17 to reprove those who look upon themselves as the cause of what they have received, telling them: "Say not my own might, or the strength of my right hand has acquired me all this power, but remember always the Lord your God, who gives you the might to acquire power." And Philo read Deuteronomy 9:4–5 to address those who think that they deserve what they have received when it says, "You do not enter into this land to possess it because of your righteousness, or because of the holiness of your heart; but, in the first place, because of the iniquity of these nations, since God has brought on them the destruction of wickedness; and in the second place, that He may establish the covenant that He swore to our Fathers." Philo interpreted the term "covenant" figuratively to mean God’s graces. Thus Philo concluded that if we discard forgetfulness, ingratitude, and self-love, we shall not longer through our delay miss attaining the genuine worship of God, but we shall meet God, having prepared ourselves to do the things that God commands us.[106]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[107]

Deuteronomy chapter 21

Deuteronomy 21:10–14 — the beautiful captive

The Gemara taught that Deuteronomy 21:10–14 provided the law of taking a beautiful captive only as an allowance for human passions. The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that taking a beautiful captive according to the strictures of Deuteronomy 21:10–14 was better than taking beautiful captives without restriction, just as it was better for Jews to eat the meat of a ritually slaughtered ill animal than to eat the meat of an ill animal that had died on its own. The Rabbis interpreted the words "and you see among the captives" in Deuteronomy 21:11 to mean that the provisions applied only if the soldier set his eye upon the woman when taking her captive, not later. They interpreted the words "a woman" in Deuteronomy 21:11 to mean that the provisions applied even to a woman who was married before having been taken captive. They interpreted the words "and you have a desire" in Deuteronomy 21:11 to mean that the provisions applied even if the woman was not beautiful. They interpreted the word "her" in Deuteronomy 21:11 to mean that the provisions allowed him to take her alone, not her and her companion. They interpreted the words "and you shall take" in Deuteronomy 21:11 to mean that the soldier could have marital rights over her. They interpreted the words "to you to wife" in Deuteronomy 21:11 to mean that the soldier could not take two women, one for himself and another for his father, or one for himself and another for his son. And they interpreted the words "then you shall bring her home" in Deuteronomy 21:12 to mean that the soldier could not molest her on the battlefield. Rav said that Deuteronomy 21:10–14 permitted a priest to take a beautiful captive, while Samuel maintained that it was forbidden.[108]

A Baraita taught that the words of Deuteronomy 21:10, "And you carry them away captive," were meant to include Canaanites who lived outside the land of Israel, teaching that if they repented, they would be accepted.[109]

The Gemara taught that the procedure of Deuteronomy 21:12–13 applied only when the captive did not accept the commandments, for if she accepted the commandments, then she could be immersed in a ritual bath (מִקְוֶה, mikveh), and she and the soldier could marry immediately.[110] Rabbi Eliezer interpreted the words "and she shall shave her head and do her nails" in Deuteronomy 21:12 to mean that she was to cut her nails, but Rabbi Akiva interpreted the words to mean that she was to let them grow. Rabbi Eliezer reasoned that Deuteronomy 21:12 specified an act with respect to the head and an act with respect to the nails, and as the former meant removal, so should the latter. Rabbi Akiva reasoned that Deuteronomy 21:12 specified disfigurement for the head, so it must mean disfigurement for the nails, as well.[111]

Rabbi Eliezer interpreted the words "bewail her father and her mother" in Deuteronomy 21:13 to mean her actual father and mother. But Rabbi Akiva interpreted the words to mean idolatry, citing Jeremiah 2:27. A Baraita taught that "a full month" meant 30 days. But Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar interpreted Deuteronomy 21:13 to call for 90 days — 30 days for "month," 30 days for "full," and 30 days for "and after that." Rabina said that one could say that "month" meant 30 days, "full" meant 30 days, and "and after that" meant an equal number (30 plus 30) again, for a total of 120 days.[112]

Deuteronomy 21:15–17 — inheritance among the sons of two wives

The Mishnah and the Talmud interpreted the laws of the firstborn’s inheritance in Deuteronomy 21:15–17 in Mishnah Bava Batra 8:4–5,[113] Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 122b–34a,[114] Mishnah Bekhorot 8:9,[115] and Babylonian Talmud Bekhorot 51b–52b.[116] The Mishnah interpreted Deuteronomy 21:17 to teach that a son and a daughter have equal inheritance rights, except that a firstborn son takes a double portion in his father’s estate but does not take a double portion in his mother’s estate.[117] The Mishnah taught that they disregarded a father who said, "My firstborn son shall not inherit a double portion," or "My son shall not inherit with his brothers," because the father’s stipulation would be contrary to Deuteronomy 21:17. But a father could distribute his property as gifts during his lifetime so that one son received more than another, or so that the firstborn received merely an equal share, so long as the father did not try to make these conveyances as an inheritance upon his death.[118]

The Gemara recounted a discussion regarding the right of the firstborn in Deuteronomy 21:17. Once Rabbi Jannai was walking, leaning on the shoulder of Rabbi Simlai his attendant, and Rabbi Judah the Prince came to meet them. Rabbi Judah the Prince asked Rabbi Jannai what the Scriptural basis was for the proposition that a son takes precedence over a daughter in the inheritance of a mother's estate. Rabbi Jannai replied that the plural use of the term "tribes" in the discussion of the inheritance of the daughters of Zelophehad in Numbers 36:8 indicates that the mother's tribe is to be compared to the father's tribe, and as in the case of the father's tribe, a son takes precedence over a daughter, so in the case of the mother's tribe, a son should take precedence over a daughter. Rabbi Judah the Prince challenged Rabbi Jannai, saying that if it this were so, one could say that as in the case of the father's tribe, a firstborn takes a double portion, so in the case of the mother's tribe would a firstborn take a double portion. Rabbi Jannai dismissed the remark of Rabbi Judah the Prince. The Gemara then inquired why it is true that a firstborn son takes a double share in his father's estate but not his mother's. Abaye replied that Deuteronomy 21:17 says, "of all that he [the father] has," implying all that "he" (the father) has and not all that "she" (the mother) has. The Gemara asked whether the proposition that a firstborn son takes a double portion only in the estate of his father might apply only in the case where a bachelor married a widow (who had children from her first marriage, and thus the father's firstborn son was not that of the mother). And thus where a bachelor married a virgin (so that the firstborn son of the father would also be the firstborn son of the mother) might the firstborn son also take a double portion in his mother’s estate? Rav Nahman bar Isaac replied that Deuteronomy 21:17 says, "for he [the firstborn son] is the first-fruits of his [the father’s] strength," from which we can infer that the law applies to the first fruits of the father’s strength and not the first-fruits of the mother’s strength. The Gemara replied that Deuteronomy 21:17 teaches that though a son was born after a miscarriage (and thus did not "open the womb" and is not regarded as a firstborn son for purposes of "sanctification to the Lord" and "redemption from the priest" in Exodus 13:2) he is nonetheless regarded as the firstborn son for purposes of inheritance. Deuteronomy 21:17 thus implies that only the son for whom the father's heart grieves is included in the law, but a miscarriage, for which the father's heart does not grieve, is excluded. (And thus, since Deuteronomy 21:17 is necessary for this deduction, it could not have been meant for the proposition that the law applies to the first fruits of the father’s strength and not of the mother’s strength.) But then the Gemara reasoned that if Deuteronomy 21:17 is necessary for excluding miscarriages, then Deuteronomy 21:17 should have read, "for he is the first-fruits of strength," but Deuteronomy 21:17 in fact says, "his strength." Thus one may deduce two laws from Deuteronomy 21:17. But the Gemara objected further that still that the words of Deuteronomy 21:17, "the first-fruits of his [the father’s] strength," not her strength, might apply only to the case of a widower (who had children from his first wife) who married a virgin (since the first son from the second marriage would be only the wife's firstborn, not the husband’s). But where a bachelor married a virgin (and thus the son would be the firstborn of both the father and the mother), the firstborn son might take a double portion also in his mother’s estate. But Raba concluded that Deuteronomy 21:17 states, "the right of the firstborn is his [the father’s]," and this indicates that the right of the firstborn applies to a man’s estate and not to a woman’s.[119]

A Midrash told that the Ishmaelites came before Alexander the Great to dispute the birthright with Israel, accompanied by the Canaanites and the Egyptians. The Ishmaelites based their claim on Deuteronomy 21:17, “But he shall acknowledge the firstborn, the son of the hated,” and Ishmael was the firstborn. Gebiah the son of Kosem representing the Jews, asked Alexander whether a man could not do as he wished to his sons. When Alexander replied that a man could, Gebiah quoted Genesis 25:5, “And Abraham gave all that he had to Isaac.” The Ishmaelites asked where the deed of gift to his other sons was. Gebiah replied by quoting Genesis 25:7, “But to the sons of the concubines, whom Abraham had, Abraham gave gifts.” Thereupon the Ishmaelites departed in shame.[120]

Deuteronomy 21:18–21 — the wayward son

Chapter 8 of tractate Sanhedrin in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the wayward and rebellious son (בֵּן סוֹרֵר וּמוֹרֶה, ben sorer umoreh) in Deuteronomy 21:18–21.[121] A Baraita taught that there never was a "stubborn and rebellious son" and never would be, and that Deuteronomy 21:18–21 was written merely that we might study it and receive reward for the studying. But Rabbi Jonathan said that he saw a stubborn and rebellious son and sat on his grave.[122]

The Mishnah interpreted the words "a son" in Deuteronomy 21:18 to teach that provision applied to "a son," but not a daughter, and to "a son," but not a full-grown man. The Mishnah exempted a minor, because minors did not come within the scope of the commandments. And the Mishnah deduced that a boy became liable to being considered "a stubborn and rebellious son" from the time that he grew two genital pubic hairs until his pubic hair grew around his genitalia.[123] Rav Judah taught in Rav’s name that Deuteronomy 21:18 implied that the son had to be nearly a man.[124]

The Mishnah interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 21:20 to exclude from designation as a "stubborn and rebellious son" a boy who had a parent with any of a number of physical characteristics. The Mishnah interpreted the words "then his father and his mother shall lay hold on him" to exclude a boy if one of his parents had a hand or fingers cut off. The Mishnah interpreted the words "and bring him out" to exclude a boy who had a lame parent. The Mishnah interpreted the words "and they shall say" to exclude a boy who had a parent who could not speak. The Mishnah interpreted the words "this our son" to exclude a boy who had a blind parent. The Mishnah interpreted the words "he will not obey our voice" to exclude a boy who had a deaf parent.[125]

Deuteronomy chapter 22

The first two chapters of tractate Bava Metzia in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of lost property in Deuteronomy 22:1–3.[126] The Mishnah read the reference to "your brother’s ox or his sheep" in Deuteronomy 22:1 to apply to any domestic animal.[127] The Mishnah read the emphatic words of Deuteronomy 22:1, "you shall surely return them," repeating the verb "return" in the Hebrew, to teach that Deuteronomy 22:1 required a person to return a neighbor’s animal again and again, even if the animal kept running away four or five times.[128] And Raba taught that Deuteronomy 22:1 required a person to return the animal even a hundred times.[129] If one found an identifiable item and the identity of the owner was unknown, the Mishnah taught that the finder was required to announce it. Rabbi Meir taught that the finder was obliged to announce it until his neighbors could know of it. Rabbi Judah maintained that the finder had to announce it until three festivals had passed plus an additional seven days after the last festival, allowing three days for going home, three days for returning, and one day for announcing.[130]

The Gemara read the emphatic words of Deuteronomy 22:4, "you shall surely help . . . to lift," repeating the verb in the Hebrew, to teach that Deuteronomy 22:4 required a person to lift a neighbor’s animal alone, even if the animal’s owner was too sick or too old to help.[129] Similarly, the Sifre read the emphatic words of Deuteronomy 22:4 to teach that Deuteronomy 22:4 required a person to help lift a neighbor’s animal even if they lifted it, it fell again, and again, even five times.[131]

Chapter 12 of tractate Chullin in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of sending the mother bird away from the nest (שילוח הקן, shiluach hakein) in Deuteronomy 22:6–7.[132] The Mishnah read Deuteronomy 22:6–7 to require a person to let the mother bird go again and again, even if the mother bird kept coming back to the nest four or five times.[133] And the Gemara taught that Deuteronomy 22:6–7 required a person to let the mother bird go even a hundred times.[129]

.jpg)

Tractate Kilayim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of separating diverse species in Deuteronomy 22:9–11.[134]

The Mishnah employed the prohibitions of Deuteronomy 22:9, 22:10, and 22:11 to imagine how one could with one action violate up to nine separate commandments. One could (1) plow with an ox and a donkey yoked together (in violation of Deuteronomy 22:10) (2 and 3) that are two animals dedicated to the sanctuary, (4) plowing mixed seeds sown in a vineyard (in violation of Deuteronomy 22:9), (5) during a Sabbatical year (in violation of Leviticus 25:4), (6) on a Festival-day (in violation of, for example, Leviticus 23:7), (7) when the plower is a priest (in violation of Leviticus 21:1) and (8) a Nazirite (in violation of Numbers 6:6) plowing in a contaminated place. Chananya ben Chachinai said that the plower also may have been wearing a garment of wool and linen (in violation of Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11). They said to him that this would not be in the same category as the other violations. He replied that neither is the Nazirite in the same category as the other violations.[135]

Rabbi Joshua of Siknin taught in the name of Rabbi Levi that the Evil Inclination criticizes four laws as without logical basis, and Scripture uses the expression "statute" (חֹק, chok) in connection with each: the laws of (1) a brother’s wife (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10), (2) mingled kinds (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), (3) the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16), and (4) the red cow (in Numbers 19).[136]

Leviticus 18:4 calls on the Israelites to obey God’s "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim) and "ordinances" (מִּשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim). The Rabbis in a Baraita taught that the "ordinances" (מִּשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim) were commandments that logic would have dictated that we follow even had Scripture not commanded them, like the laws concerning idolatry, adultery, bloodshed, robbery, and blasphemy. And "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim) were commandments that the Adversary challenges us to violate as beyond reason, like those relating to שַׁעַטְנֵז, shaatnez (in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11); חליצה, chalitzah (in Deuteronomy 25:5–10); purification of the person with skin disease, צָּרַעַת, tzara’at (in Leviticus 14), and the scapegoat (in Leviticus 16). So that people do not think these "ordinances" (מִּשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim) to be empty acts, in Leviticus 18:4, God says, "I am the Lord," indicating that the Lord made these statutes, and we have no right to question them.[137]

Similarly, reading Leviticus 18:4, "My ordinances (מִשְׁפָּטַי, mishpatai) shall you do, and My statutes (חֻקֹּתַי, chukotai) shall you keep," the Sifra distinguished "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim) from "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim). The term "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim), taught the Sifra, refers to rules that even had they not been written in the Torah, it would have been entirely logical to write them, like laws pertaining to theft, sexual immorality, idolatry, blasphemy and murder. The term "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim), taught the Sifra, refers to those rules that the impulse to do evil (יצר הרע, yetzer hara) and the nations of the world try to undermine, like eating pork (prohibited by Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8), wearing wool-linen mixtures (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shatnez, prohibited by Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), release from levirate marriage (חליצה, chalitzah, mandated by Deuteronomy 25:5–10), purification of a person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora, regulated in Leviticus 13–14), and the goat sent off into the wilderness (the scapegoat, regulated in Leviticus 16). In regard to these, taught the Sifra, the Torah says simply that God legislated them and we have no right to raise doubts about them.[138]

Rabbi Eleazar ben Azariah taught that people should not say that they do not want to wear a wool-linen mixture (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shatnez, prohibited by Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), eat pork (prohibited by Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8), or be intimate with forbidden partners (prohibited by Leviticus 18 and 20), but rather should say that they would love to, but God has decreed that they not do so. For in Leviticus 20:26, God says, "I have separated you from the nations to be mine." So one should separate from transgression and accept the rule of Heaven.[139]

Chapter 3 of tractate Ketubot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of seducers and rapists in Deuteronomy 22:25–29.[140]

Deuteronomy chapter 23

Rabbi Abba bar Kahana said that all of Balaam’s curses, which God turned into blessings, reverted to curses (and Balaam’s intention was eventually fulfilled), except for Balaam’s blessing of Israel’s synagogues and schoolhouses, for Deuteronomy 23:6 says, “But the Lord your God turned the curse into a blessing for you, because the Lord your God loved you,” using the singlular “curse,” and not the plural “curses” (so that God turned only the first intended curse permanently into a blessing, that concerning synagogues and school-houses, which are destined never to disappear from Israel). Rabbi Johanan taught that God reversed every curse that Balaam intended into a blessing. Thus Balaam wished to curse the Israelites to have no synagogues or school-houses, for Numbers 24:5, “How goodly are your tents, O Jacob,” refers to synagogues and school-houses. Balaam wished that the Shechinah should not rest upon the Israelites, for in Numbers 24:5, “and your tabernacles, O Israel,” the Tabernacle symbolizes the Divine Presence. Balaam wished that the Israelites’ kingdom should not endure, for Numbers 24:6, “As the valleys are they spread forth,” symbolizes the passing of time. Balaam wished that the Israelites might have no olive trees and vineyards, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, “as gardens by the river's side.” Balaam wished that the Israelites’ smell might not be fragrant, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, “as the trees of lign aloes that the Lord has planted.” Balaam wished that the Israelites’ kings might not be tall, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, “and as cedar trees beside the waters.” Balaam wished that the Israelites might not have a king who was the son of a king (and thus that they would have unrest and civil war), for in Numbers 24:6, he said, “He shall pour the water out of his buckets,” signifying that one king would descend from another. Balaam wished that the Israelites’ kingdom might not rule over other nations, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, “and his seed shall be in many waters.” Balaam wished that the Israelites’ kingdom might not be strong, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, “and his king shall be higher than Agag. Balaam wished that the Israelites’ kingdom might not be awe-inspiring, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, “and his kingdom shall be exalted.[141]

Rabbi Jose noted that the law of Deuteronomy 23:8 rewarded the Egyptians for their hospitality notwithstanding that Genesis 47:6 indicated that the Egyptians befriended the Israelites only for their own benefit. Rabbi Jose concluded that if Providence thus rewarded one with mixed motives, Providence will reward even more one who selflessly shows hospitality to a scholar.[142]

Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman compared the laws of camp hygiene in Deuteronomy 23:10–15 to the case of a High Priest who was walking on the road and met a layman who wanted to walk with him. The High Priest answered the layman that he was a priest and needed to go along a ritually clean path, and that it would thus not be proper for him to walk among graves. The High Priest said that if the layman would come with the priest, it was well and good, but if not, the priest would eventually have to leave the layman and go his own way. So Moses told the Israelites, in the words of Deuteronomy 23:15, "The Lord your God walks in the midst of your camp, to deliver you."[143]

Rabbi Eleazar ben Perata taught that manna counteracted the ill effects of foreign foods on the Israelites. But the Gemara taught after the Israelites complained about the manna in Numbers 21:5, God burdened the Israelites with the walk of three parasangs to get outside their camp to answer the call of nature. And it was then that the command of Deuteronomy 23:14, “And you shall have a paddle among your weapons,” began to apply to the Israelites.[144]

The Mishnah taught that a red cow born by a caesarean section, the hire of a harlot, or the price of a dog was invalid for the purposes of Numbers 19. Rabbi Eliezer ruled it valid, as Deuteronomy 23:19 states, "You shall not bring the hire of a harlot or the price of a dog into the house of the Lord your God," and the red cow was not brought into the house.[145]

In part by reference to Deuteronomy 23:19, the Gemara interpreted the words in Leviticus 6:2, "This is the law of the burnt-offering: It is that which goes up on its firewood upon the altar all night into the morning." From the passage, "which goes up on its firewood upon the altar all night," the Rabbis deduced that once a thing had been placed upon the altar, it could not be taken down all night. Rabbi Judah taught that the words "This . . . goes up on . . . the altar all night" exclude three things. According to Rabbi Judah, they exclude (1) an animal slaughtered at night, (2) an animal whose blood was spilled, and (3) an animal whose blood was carried out beyond the curtains. Rabbi Judah taught that if any of these things had been placed on the altar, it was brought down. Rabbi Simeon noted that Leviticus 6:2 says "burnt-offering." From this, Rabbi Simeon taught that one can only know that a fit burnt-offering remained on the altar. But Rabbi Simeon taught that the phrase "the law of the burnt-offering" intimates one law for all burnt-offerings, namely, that if they were placed on the altar, they were not removed. Rabbi Simeon taught that this law applied to animals that were slaughtered at night, or whose blood was spilt, or whose blood passed out of the curtains, or whose flesh spent the night away from the altar, or whose flesh went out, or were unclean, or were slaughtered with the intention of burning its flesh after time or out of bounds, or whose blood was received and sprinkled by unfit priests, or whose blood was applied below the scarlet line when it should have been applied above, or whose blood was applied above when it should have been applied below, or whose blood was applied outside when it should have been applied within, or whose blood was applied within when it should have been applied outside, or a Passover-offering or a sin-offering that one slaughtered for a different purpose. Rabbi Simeon suggested that one might think that law would also include an animal used for bestiality, set aside for an idolatrous sacrifice or worshipped, a harlot's hire or the price of a dog (as referred to in Deuteronomy 23:19), or a mixed breed, or a trefah (a torn or otherwise disqualified animal), or an animal calved through the cesarean section. But Rabbi Simeon taught that the word "This" serves to exclude these. Rabbi Simeon explained that he included the former in the general rule because their disqualification arose in the sanctuary, while he excluded the latter because their disqualification did not arise in the sanctuary.[146]

Tractates Nedarim and Shevuot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of vows and oaths in Exodus 20:7, Leviticus 5:1–10 and 19:12, Numbers 30:2–17, and Deuteronomy 23:24.[147]

Deuteronomy chapter 24

Tractate Gittin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of divorce in Deuteronomy 24:1.[148]

The Mishnah interpreted the prohibition of Deuteronomy 24:6, "No man shall take the mill or the upper millstone to pledge," to teach that a creditor who took a mill as security for a loan transgressed a negative commandment and was guilty on account of two forbidden utensils. The Mishnah interpreted Deuteronomy 24:6 to prohibit a creditor from taking in security not only millstones, but everything employed in the preparation of food for human consumption. For the continuation of Deuteronomy 24:6 says of the creditor, "for he takes a man's life to pledge" (and the debtor needs such utensils to prepare the food necessary to sustain life).[149]

A Midrash interpreted the words of Genesis 37:24, "there was no water in it," to teach that there was no recognition of Torah in the pit into which Joseph’s brothers cast him, as Torah is likened to water, as Isaiah 55:1 says, "everyone that thirsts, come for water." For the Torah (in Deuteronomy 24:7) says, "If a man be found stealing any of his brethren of the children of Israel . . . and sell him, then that thief shall die," and yet Joseph’s brothers sold their brother.[150]

The Gemara read the emphatic words of Deuteronomy 24:12–13, "you shall surely restore . . . the pledge," repeating the verb in the Hebrew, to teach that Deuteronomy 24:12–13 required a lender to restore the pledge whether or not the lender took the pledge with the court’s permission. And the Gemara taught that the Torah provided similar injunctions in Deuteronomy 24:12–13 and Exodus 22:25 to teach that a lender had to return a garment worn during the day before sunrise, and return a garment worn during the night before sunset.[151]

Rabbi Eliezer the Great taught that the Torah warns against wronging a stranger in 36, or others say 46, places (including Deuteronomy 24:14–15 and 17–22).[152] The Gemara went on to cite Rabbi Nathan’s interpretation of Exodus 22:20, "You shall neither wrong a stranger, nor oppress him; for you were strangers in the land of Egypt," to teach that one must not taunt one’s neighbor about a flaw that one has oneself. The Gemara taught that thus a proverb says: If there is a case of hanging in a person’s family history, do not say to the person, "Hang up this fish for me."[153]

The Mishnah interpreted Leviticus 19:13 and Deuteronomy 24:14–15 to teach that a worker engaged by the day could collect the worker’s wages all of the following night. If engaged by the night, the worker could collect the wages all of the following day. If engaged by the hour, the worker could collect the wages all that day and night. If engaged by the week, month, year, or 7-year period, if the worker’s time expired during the day, the worker could collect the wages all that day. If the worker’s time expired during the night, the worker could collect the wages all that night and the following day.[154]

The Mishnah taught that the hire of persons, animals, or utensils were all subject to the law of Deuteronomy 24:15 that "in the same day you shall give him his hire" and the law of Leviticus 19:13 that "the wages of a hired servant shall not abide with you all night until the morning." The employer became liable only when the worker or vendor demanded payment from the employer. Otherwise, the employer did not infringe the law. If the employer gave the worker or vendor a draft on a shopkeeper or a money changer, the employer complied with the law. A worker who claimed the wages within the set time could collect payment if the worker merely swore that the employer had not yet paid. But if the set time had passed, the worker’s oath was insufficient to collect payment. Yet if the worker had witnesses that the worker had demanded payment (within the set time), the worker could still swear and receive payment.[155]

The Mishnah taught that the employer of a resident alien was subject to the law of Deuteronomy 24:15 that "in the same day you shall give him his hire" (as Deuteronomy 24:14 refers to the stranger), but not to the law of Leviticus 19:13 that "the wages of a hired servant shall not abide with you all night until the morning."[155]

The Gemara reconciled apparently discordant verses touching on vicarious responsibility. The Gemara noted that Deuteronomy 24:16 states: "The fathers shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the fathers; every man shall be put to death for his own sin," but Exodus 20:4 (20:5 in NJPS) says: "visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children." The Gemara cited a Baraita that interpreted the words "the iniquities of their fathers shall they pine away with them" in Leviticus 26:39 to teach that God punishes children only when they follow their parents’ sins. The Gemara then questioned whether the words "they shall stumble one upon another" in Leviticus 26:37 do not teach that one will stumble through the sin of the other, that all are held responsible for one another. The Gemara answered that the vicarious responsibility of which Leviticus 26:37 speaks is limited to those who have the power to restrain their fellow from evil but do not do so.[156]

Reading the words of Deuteronomy 24:17, "You shall not take a widow’s raiment to pledge," the Mishnah taught that a person may not take a pledge from a widow whether she is rich or poor.[157] The Gemara explained that Rabbi Judah (reading the text literally) expounded the view that no pledge may be taken from her whether she is rich or poor. Rabbi Simeon, however, (addressing the purpose of the text) taught that a wealthy widow was subject to distraint, but not a poor one, for the creditor was bound (by Deuteronomy 24:12–13) to return the pledge to her, and would bring her into disrepute among her neighbors (by her frequent visits to the creditor).[158]

Tractate Peah in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the harvest of the corner of the field and gleanings to be given to the poor in Leviticus 19:9–10 and 23:22, and Deuteronomy 24:19–21.[159]

The Mishnah taught that the Torah defines no minimum or maximum for the donation of the corners of one’s field to the poor.[160] But the Mishnah also taught that one should not make the amount left to the poor less than one-sixtieth of the entire crop. And even though no definite amount is given, the amount given should accord with the size of the field, the number of poor people, and the extent of the yield.[161]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that one who cultivates land in which one can plant a quarter kav of seed is obligated to give a corner to the poor. Rabbi Joshua said land that yields two seah of grain. Rabbi Tarfon said land of at least six handbreadths by six handbreadths. Rabbi Judah ben Betera said land that requires two strokes of a sickle to harvest, and the law is as he spoke. Rabbi Akiva said that one who cultivates land of any size is obligated to give a corner to the poor and the first fruits.[162]

The Mishnah taught that the poor could enter a field to collect three times a day — in the morning, at midday, and in the afternoon. Rabban Gamliel taught that they said this only so that landowners should not reduce the number of times that the poor could enter. Rabbi Akiva taught that they said this only so that landowners should not increase the number of times that the poor had to enter. The landowners of Beit Namer used to harvest along a rope and allowed the poor to collect a corner from every row.[163]

The Mishnah taught that if a wife foreswore all benefit from other people, her husband could not annul his wife’s vow, but she could still benefit from the gleanings, forgotten sheaves, and the corner of the field that Leviticus 19:9–10 and 23:22, and Deuteronomy 24:19–21 commanded farmers to leave for the poor.[164]

Deuteronomy chapter 25

Tractate Yevamot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of levirate marriage (יִבּוּם, yibbum) in Deuteronomy 25:5–10.[165]

Interpreting the laws of Levirite marriage (יִבּוּם, yibbum) under Deuteronomy 25:5–6, the Gemara read Exodus 21:4 to address a Hebrew slave who married the Master’s Canaanite slave, and deduced from Exodus 21:4 that the children of such a marriage were also considered Canaanite slaves and thus that their lineage flowed from their mother, not their father. The Gemara used this analysis of Exodus 21:4 to explain why Mishnah Yevamot 2:5[166] taught that the son of a Canaanite slave mother does not impose the obligation of Levirite marriage (יִבּוּם, yibbum) under Deuteronomy 25:5–6.[167]

Chapter 3 in tractate Makkot in the Mishnah and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of punishment by lashes in Deuteronomy 25:1–3.[168]

The Gemara interpreted Deuteronomy 25:13–15 to teach that both one's wealth and one's necessities depend on one's honesty.[169]

Reading Deuteronomy 25:15, Rabbi Levi taught that blessed actions bless those who are responsible for them, and cursed actions curse those who are responsible for them. The Midrash interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 25:15, "A perfect and just weight you shall have," to mean that if one acts justly, one will have something to take and something to give, something to buy and something to sell. Conversely, the Midrash read Deuteronomy 25:13–14 to teach, "You shall not have (possessions if there are) in your bag diverse weights, a great and a small. You shall not have (possessions if there are) in your house diverse measures, a great and a small." Thus, if one does employ deceitful measures, one will not have anything to take or give, to buy or sell. The Midrash taught that God tells businesspeople that they "may not make" one measure great and another small, but if they do, they "will not make" a profit. The Midrash likened this commandment to that of Exodus 20:19 (20:20 in the NJPS) "You shall not make with Me gods of silver, or gods of gold, you shall not make," for if a person did make gods of silver and gold, then that person would not be able to afford to have even gods of wood or stone.[170]

Rabbi Levi taught that the punishment for false weights or measures (discussed at Deuteronomy 25:13–16) was more severe than that for having intimate relations with forbidden relatives (discussed at Leviticus 18:6–20). For in discussing the case of forbidden relatives, Leviticus 18:27 uses the Hebrew word אֵל, eil, for the word "these," whereas in the case of false weights or measures, Deuteronomy 25:16 uses the Hebrew word אֵלֶּה, eileh, for the word "these" (and the additional ה, eh at the end of the word implies additional punishment.) The Gemara taught that one can derive that אֵל, eil, implies rigorous punishment from Ezekiel 17:13, which says, "And the mighty (אֵילֵי, eilei) of the land he took away." The Gemara explained that the punishments for giving false measures are greater than those for having relations with forbidden relatives because for forbidden relatives, repentance is possible (as long as there have not been children), but with false measure, repentance is impossible (as one cannot remedy the sin of robbery by mere repentance; the return of the things robbed must precede it, and in the case of false measures, it is practically impossible to find out all the members of the public who have been defrauded).[171]

Rabbi Hiyya taught that the words of Leviticus 19:35, "You shall do no unrighteousness in judgment," apply to judgment in law. But a Midrash noted that Leviticus 19:15 already mentioned judgment in law, and questioned why Leviticus 19:35 would state the same proposition again and why Leviticus 19:35 uses the words, "in judgment, in measures." The Midrash deduced that Leviticus 19:35 teaches that a person who measures is called a judge, and one who falsifies measurements is called by the five names "unrighteous," "hated," "repulsive," "accursed," and an "abomination," and is the cause of these five evils. Rabbi Banya said in the name of Rav Huna that the government comes and attacks that generation whose measures are false. The Midrash found support for this from Proverbs 11:1, "A false balance is an abomination to the Lord," which is followed by Proverbs 11:2, "When presumption comes, then comes shame." Reading Micah 6:11, "Shall I be pure with wicked balances?" Rabbi Berekiah said in the name of Rabbi Abba that it is impossible for a generation whose measures are false to be meritorious, for Micah 6:11 continues, "And with a bag of deceitful weights" (showing that their holdings would be merely illusory). Rabbi Levi taught that Moses also hinted to Israel that a generation with false measures would be attacked. Deuteronomy 25:13–14 warns, "You shall not have in your bag diverse weights . . . you shall not have in your house diverse measures." But if one does, one will be attacked, as Deuteronomy 25:16, reports, "For all who do such things, even all who do unrighteously, are an abomination to the Lord your God," and then immediately following, Deuteronomy 25:17 says, "Remember what Amalek did to you (attacking Israel) by the way as you came forth out of Egypt."[172]

Rabbi Judah said that three commandments were given to the Israelites when they entered the land: (1) the commandment of Deuteronomy 17:14–15 to appoint a king, (2) the commandment of Deuteronomy 25:19 to blot out Amalek, and (3) the commandment of Deuteronomy 12:10–11 to build the Temple in Jerusalem. Rabbi Nehorai, on the other hand, said that Deuteronomy 17:14–15 did not command the Israelites to choose a king, but was spoken only in anticipation of the Israelites’ future complaints, as Deuteronomy 17:14 says, "And (you) shall say, ‘I will set a king over me.’"[173]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[174]

Deuteronomy chapter 22

Medieval rabbi David Kimchi stated that a parapet (Deuteronomy 22:8) needed to be "ten hands high, or more, that a person might not fall from it".[175]

Deuteronomy chapter 23

Maimonides used Deuteronomy 23:8 to interpret how far to extend the principle of charity. Maimonides taught that the Law correctly says in Deuteronomy 15:11, "You shall open your hand wide to your brother, to your poor." Maimonides continued that the Law taught how far we have to extend this principle of treating kindly every one with whom we have some relationship — even if the other person offended or wronged us, even if the other person is very bad, we still must have some consideration for the other person. Thus Deuteronomy 23:8 says: "You shall not abhor an Edomite, for he is your brother." And if we find a person in trouble, whose assistance we once enjoyed, or of whom we have received some benefit, even if that person has subsequently wronged us, we must bear in mind that person’s previous good conduct. Thus Deuteronomy 23:8 says: "You shall not abhor an Egyptian, because you were a stranger in his land," although the Egyptians subsequently oppressed the Israelites very much.[176]

Deuteronomy chapter 25

Reading the words of Deuteronomy 24:17, "You shall not take a widow’s raiment to pledge," Maimonides taught that collateral may not be taken from a widow, whether she is rich or poor, whether it is taken at the time the loan is given or after the time the loan is given, and even when a court would supervise the matter. Maimonides continued that if a creditor takes such collateral, it must be returned, even against the creditor’s will. If the widow admits the debt, she must pay, but if she denies its existence, she must take an oath. If the security the creditor took was lost or consumed by fire before the creditor returned it, the creditor was punished by lashes.[177]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Deuteronomy chapter 22

Professor William Dever of Lycoming College noted that most of the 100 linen and wool fragments, likely textiles used for cultic purposes, that archeologists found at Kuntillet Ajrud in the Sinai Desert (where the climate may better preserve organic materials) adhered to the regulations in Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11.[178]

Deuteronomy chapter 25

Professor James Kugel of Bar Ilan University noted that Deuteronomy shares certain favorite themes with Wisdom literature, as, for example, when Deuteronomy 25:13–16 prohibits using false weights, a specific offense also mentioned in Proverbs 11:1 and 20:10 and 23. As well, in the wisdom perspective, history is the repository of eternal truths, lessons that never grow old, and thus Deuteronomy constantly urges its readers to "remember," as Deuteronomy 25:17 does when it admonishes to "Remember what Amalek did to you." Kugel concluded that the Deuteronomist was closely connected to the world of wisdom literature.[179]

In critical analysis

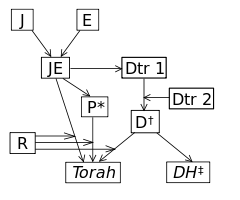

Some secular scholars who follow the Documentary Hypothesis consider all of the parashah to have been part of the original Deuteronomic Code (sometimes abbreviated Dtn) that the first Deuteronomistic historian (sometimes abbreviated Dtr 1) included in the edition of Deuteronomy that existed during Josiah’s time.[180]

Commandments

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 27 positive and 47 negative commandments in the parashah.[181]

- To keep the laws of the captive woman[182]

- Not to sell the captive woman into slavery[8]

- Not to retain the captive woman for servitude after having relations with her[8]

- The courts must hang those stoned for blasphemy or idolatry.[183]

- To bury the executed on the day that they die[184]

- Not to delay burial overnight[184]

- To return a lost object to its owner[185]

- Not to turn a blind eye to a lost object[186]

- Not to leave another’s beast lying under its burden[19]

- To lift up a load for a Jew[19]

- Women must not wear men's clothing.[21]

- Men must not wear women's clothing.[21]

- Not to take the mother bird from her children[187]

- To release the mother bird if she was taken from the nest[188]

- To build a parapet[24]

- Not to leave a stumbling block about[24]

- Not to plant grains or greens in a vineyard[25]

- Not to eat diverse seeds planted in a vineyard[25]

- Not to do work with two kinds of animals together[26]

- Not to wear cloth of wool and linen[27]

- To marry a wife by means of ketubah and kiddushin[189]

- The slanderer must remain married to his wife.[32]

- The slanderer must not divorce his wife.[32]

- The court must have anyone who merits stoning stoned to death.[190]

- Not to punish anyone compelled to commit a transgression[191]

- The rapist must marry his victim if she chooses.[192]

- The rapist is not allowed to divorce his victim.[192]

- Not to let a eunuch marry into the Jewish people[42]

- Not to let the child of a prohibited union (מַמְזֵר, mamzer) marry into the Jewish people[43]

- Not to let Moabite and Ammonite men marry into the Jewish people[44]

- Not to ever offer peace to Moab or Ammon[193]

- Not to exclude a third generation Edomite convert from marrying into the Jewish people[194]

- To exclude Egyptian converts from marrying into the Jewish people only for the first two generations[194]

- A ritually unclean person should not enter the camp of the Levites.[195]

- To prepare a place of easement in a camp[196]

- To prepare a boring-stick or spade for easement in a camp[197]

- Not to return a slave who fled into Israel from his master abroad[198]

- Not to oppress a slave who fled into Israel from his master abroad[199]

- Not to have relations with women not married by means of ketubah and kiddushin[200]

- Not to bring the wage of a harlot or the exchange price of a dog as a holy offering[201]

- Not to borrow at interest from a Jew[202]

- To lend at interest to a non-Jew if the non-Jew needs a loan, but not to a Jew[203]

- Not to be tardy with vowed and voluntary offerings[204]

- To fulfill whatever goes out from one’s mouth[205]

- To allow a hired worker to eat certain foods while under hire[59]

- That a hired hand should not raise a sickle to another’s standing grain[59]

- That a hired hand is forbidden to eat from the employer’s crops during work[60]

- To issue a divorce by means of a get document[206]

- A man must not remarry his ex-wife after she has married someone else.[207]

- Not to demand from the bridegroom any involvement, communal or military during the first year[63]

- To give him who has taken a wife, built a new home, or planted a vineyard a year to rejoice therewith[63]

- Not to demand as collateral utensils needed for preparing food[64]

- The metzora must not remove his signs of impurity.[208]

- The creditor must not forcibly take collateral.[209]

- Not to delay return of collateral when needed[210]

- To return the collateral to the debtor when needed[211]

- To pay wages on the day that they were earned[212]

- Relatives of the litigants must not testify.[73]

- A judge must not pervert a case involving a convert or orphan.[213]

- Not to demand collateral from a widow[213]

- To leave the forgotten sheaves in the field[76]

- Not to retrieve the forgotten sheaves[76]

- The precept of whiplashes for the wicked[214]

- The court must not exceed the prescribed number of lashes.[215]

- Not to muzzle an ox while plowing[80]

- The widow must not remarry until the ties with her brother-in-law are removed.[216]

- To marry a childless brother's widow (to do yibum)[216]

- To free a widow from yibum (to do חליצה, chalitzah)[217]

- To save someone being pursued by a killer, even by taking the life of the pursuer[218]

- To have no mercy on a pursuer with intent to kill[218]

- Not to possess inaccurate scales and weights even if they are not for use[219]

- To remember what Amalek did to the Jewish people[220]

- To wipe out the descendants of Amalek[91]

- Not to forget Amalek’s atrocities and ambush on the Israelites’ journey from Egypt in the desert[91]

In the liturgy

The parashah is reflected in these parts of the Jewish liturgy:

Following the Shacharit morning prayer service, some Jews recite the Six Remembrances, among which is Deuteronomy 24:9, "Remember what the Lord your God did to Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt," recalling that God punished Miriam with skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara’at).[221]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For Parashah Ki Teitzei, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Saba. Saba, in Hebrew, literally means "army." It is appropriate here, because the parashah commences with the discussion of what to do in certain cases of war with the army.

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is Isaiah 54:1–10. The haftarah is the fifth in the cycle of seven haftarot of consolation after Tisha B'Av, leading up to Rosh Hashanah.

Notes

- ↑ "Devarim Torah Stats". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Parashat Ki Teitzei". Hebcal. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ↑ Esther 1:1–10:3.

- ↑ Seder Eliyahu Rabbah chapter 20. Targum Sheni to Esther 4:13.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 136–61. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4226-0210-2.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 21:10–13.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 21:13.

- 1 2 3 Deuteronomy 21:14.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 137.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 21:15–17.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 138.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 21:18–20.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 21:21.

- 1 2 See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 139.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 21:22–23.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:1–3.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:2–3.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 140.

- 1 2 3 Deuteronomy 22:4.

- 1 2 See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 141.

- 1 2 3 Deuteronomy 22:5.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:6–7.

- 1 2 3 See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 142.

- 1 2 3 Deuteronomy 22:8.

- 1 2 3 Deuteronomy 22:9.

- 1 2 Deuteronomy 22:10.

- 1 2 Deuteronomy 22:11.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:12.

- ↑ See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 143.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:13–17.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:18–19.

- 1 2 3 Deuteronomy 22:19.

- 1 2 3 See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 144.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:20–21.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:22.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:23–24.

- 1 2 3 See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Devarim / Deuteronomy. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 145.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:25–27.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 22:28–29.

- ↑ Deuteronomy 23:1.