Ken (magazine)

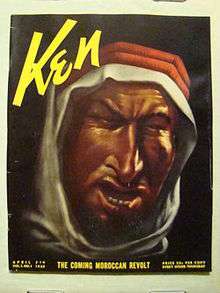

Ken was a short-lived illustrated magazine first issued on April 7, 1938. It was a controversial, political, large format magazine with full page photo spreads, published every two weeks on Thursdays.[1] It contained both articles and stories.

History and profile

Ken was founded in March 1938 by publisher David A. Smart and editor Arnold Gingrich, who earlier had founded Esquire.[2][3] Initial publication was delayed due to difficulties in assembling an editorial team. Jay Allen was the first editor hired, and he began to assemble a staff drawing heavily from the political left. Smart and Gingrich found his work unsatisfactory and quickly fired Allen and most of his new men, replacing him with George Seldes; but as Seldes's left-wing views provoked little sympathy from potential advertisers, he was soon downgraded although not fired. Microbe Hunters author Paul de Kruif was brought on as an editor, but was not able to devote full-time to the project.[2]

Smart and Gingrich then took more direct editorial control and launched the magazine with contributors including Seldes, Ernest Hemingway, John Spivak, Raymond Gram Swing, Manuel Komroff, critic Burton Rascoe, and sportswriter Herb Graffis.[2] Sam Berman contributed caricatures, and David Low cartoons.[4]

Some of the politicians with photo layouts in the magazine included Presidents Calvin Coolidge, Grover Cleveland, Thomas Harding, Franklin D. Roosevelt and as well as many prominent people in German politics.[1]

The publication was investigated 1938 for being Communist leaning.[5] However its editor Arnold Gingrich denied that the publication had any political slant.

Ken ceased publication in the fall of 1939.[3][6]

Ernest Hemingway's involvement

The first fourteen issues of Ken featured articles by Ernest Hemingway on the Spanish Civil War. In the first issue, of which his article begins on page 36, it is revealed in a caption that Hemingway was initially contracted and announced to be an editor of Ken, but had thus far taken no part in the editing of the magazine, nor in the formation of its policies. The caption goes on to reveal "If he sees eye to eye with us on Ken, we would like to have him as an editor. If not, he will remain as a contributor until he is fired or quits."[7] The disclaimer was written at Hemingway's insistence, as he felt that Ken's politics might be "liberal-phoney" and did not wish to be too closely associated with it.[2]

References

- 1 2 The Dean (June 24, 2008). "Vintage Ken Magazine: Not For The Decorator". Collector's Quest. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Press: Insiders". Time. March 21, 1938. Retrieved June 29, 2014. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "Ken's End". Time. July 10, 1939. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ↑ Chris Mullen. "Ken". The Visual Telling of Stories.

- ↑ Subcommittee of the Special Committee To Investigate Un-American Activities, United States House of Representatives (1938). "Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States, Thursday October 6, 1938 (hearing transcript)". Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States. Washington, D. C.: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 1221–1227. LCCN 41011564. OCLC 3350505. OL 7053152M. Dewey 335.0973, Library of Congress E743.5 .A4. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ Michael Denning (1998). The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. Verso. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-85984-170-9. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Ken Magazine". 1 (1). April 7, 1938.