Karoo National Park

| Karoo National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Karoo landscape | |

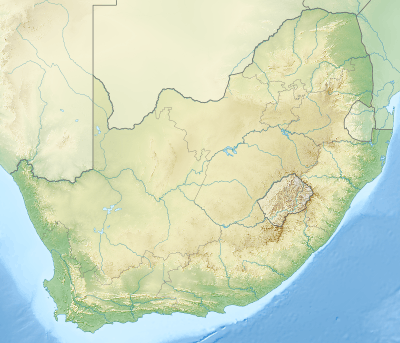

Location of the park | |

| Location | Western Cape, South Africa |

| Nearest city | Beaufort West |

| Coordinates | 32°21′S 22°35′E / 32.350°S 22.583°ECoordinates: 32°21′S 22°35′E / 32.350°S 22.583°E |

| Area | 767.9 km2 (296.5 sq mi)[1] |

| Established | 1979 |

| Governing body | South African National Parks |

| http://www.sanparks.org/parks/karoo/ | |

The Karoo National Park, founded in 1979, is a wildlife reserve in the Great Karoo area of the Western Cape, South Africa near Beaufort West. This semi-desert area covers an area of 750 square kilometres (290 sq mi).[1] The Nuweveld portion of the Great Escarpment runs through the Park. It is therefore partly in the Lower Karoo, at about 850 m above sea level, and partly in the Upper Karoo at over 1300 m altitude.[2] There are two main game viewing drives that do not require a four-wheel drive vehicle: the one to the east remains on the “Lammertjiesleegte” plains of the Lower Karoo; the other is the 49 km long circular route to the west which ascends the Klipspringer Pass on to the plateau (Upper Karoo), and eventually returns to the plains at the "Doornhoek" picnic site at the western extremity of the loop. From there it follows a south-easterly course across the plains to the beginning of the Klipspringer Pass, near the camp site and chalets. At the top of the Klipspringer Pass the Rooivalle View Point presents a magnificent panorama of the Lower Karoo.[3] The middle portion of the park, to the west of the Klipspringer Pass circular route, is easily accessible in 4x4 vehicles, and covers an extensive area, with rewarding game viewing opportunities.

The Karoo National Park is a sanctuary for herds of springbok, gemsbok (or Oryx), Cape mountain zebra, buffalo, red hartebeest, black rhinoceros, eland, kudu, klipspringer, bat-eared foxes, black-backed jackal, ostriches, and, since fairly recently, lions.[4] It also has the greatest number of tortoise species of any park in the world - five in total.[5][6] The endangered riverine rabbit has been successfully resettled here.[7] A large number of Verreaux's eagles have nests on the cliffs of the Escarpment. Martial eagles, booted eagles and the shy Cape eagle-owl are other raptors that can be seen in the Park. A wide variety of smaller birds occur in abundance, making the Park a birder’s paradise.[8] The park has also been populated with Rau Quagga which are Plains or Burchell's zebras that have been back-bred to resemble the quaggas that roamed the karoo in great profusion until the middle of the 1800s, when they were hunted to extinction. The last quagga died in Amsterdam Zoo on 12 August 1883.[9][10][11]

The Park both below and above the Great Escarpment is situated on the Beaufort group of rocks, which form part of the Karoo geological system of deposits.[12] The Beaufort sediments were laid down on a vast alluvial plain covering much of what was to become Southern Africa, when it was still part of Gondwana, beginning about 280 million years ago, and ending about 240 million years ago. These 6 km thick sediments were deposited by rivers similar in size and number to the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus rivers which drain the Himalaya mountains on the Indian subcontinent today.[13] In Gondwana, when the Beaufort sediments were being laid down, the Himalaya-sized mountains were to the south of the present South African coastline, on what is geologically known as the “Falklands Plateau”, now separated from South Africa by continental drift, and lying as severely eroded islands in the south western Atlantic Ocean.[14] A large variety of amphibians and reptiles lived on the lush vegetation of these well-watered plains, the most interesting of which were the mammal-like reptiles, which have made the Karoo paleontologically famous. Their fossils have been found all over the Karoo. Some of these fossils are on display in the Park, though none of them have been found there.

About 60 million years after the Beaufort sediments had been laid down and topped with a thick layer of desert sands, there was an outpouring of lava on to Southern Africa on a titanic scale. The entire area was covered within a very short space of time with a 1.5 km thick layer of lava, the remnants of which form the Drakensberg. In addition to flooding the African surface with lava, lava was also forced under great pressure between the sedimentary layers of the Beaufort rocks. These subterranean horizontal layers of lava solidified into what are known as dolerite sills, which can vary in thickness from a few centimeters to several meters.[14][15] Subsequent erosion of the Southern African interior re-exposed the Beaufort rocks over most of the Great Karoo. But the dolerite sills were more resistant to erosion than the Beaufort sediments, which resulted in the creation of flat topped hills all over the Karoo (the flat tops being formed by dolerite sills). The flat top edge of the Great Escarpment in the Karoo is also formed, in many places including the Karoo National Park, by a thick dolerite sill.

The vegetation consists primarily of dwarf (less than 1 m high) xerophytic shrubs with some grasses.[16][17][18] The shrubs and grasses are deciduous, mainly in response to the irregular rainfall[19][20]

The Park has a camp site for caravans and tents, chalets, an à la carte restaurant, a shop for basic necessities and curios, and picnic sites. The Park can be viewed by visitors on their own or with a guide.[8]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karoo National Park. |

References

- 1 2 "Karoo National Park". Protected Planet. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ↑ Atlas of Southern Africa. (1984). p. 102-103. Reader’s Digest Association, Cape Town

- ↑ Park map

- ↑ Van Deventer, L. & McLennan, B. (eds) (2010). “The Koup” in South Africa by Road, a Regional Guide. p. 58. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

- ↑ http://www.nature-reserve.co.za/cape-western-karoo-national-park.html

- ↑ Karoo National Park - Official Site, Sanparks. URL last accessed on April 1, 2006

- ↑ Karoo national Park, Beaufort West SA. URL last accessed on April 2, 2006.

- 1 2 Karoo National Park

- ↑ Max, D. T. (1 January 2006). "Can You Revive an Extinct Animal?". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ "Rebuilding a Species". VOA. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ↑ Geological Map of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. (1970). Council for Geoscience, Geological Survey of South Africa.

- ↑ The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World. (1999) p.28. Times Books Group, London.

- 1 2 McCarthy, T., Rubridge, B. (2005). The Story of Earth and Life. p. 202-207. Struik Publishers, Cape Town

- ↑ Karoo national Park: Western Cape, SouthAfrica-travel. URL last accessed on April 1, 2006

- ↑ Potgieter, D.J. & du Plessis, T.C. (1972) Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. Vol. 6. pp. 306-307. Nasou, Cape Town.

- ↑ Reader’s Digest Illustrated Guide to Southern Africa. (5th Ed. 1993). pp. 78-89. Reader’s Digest Association of South Africa Pty. Ltd., Cape Town.

- ↑ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Micropaedia, Vol. 6. (2007). p.750. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., Chicago.

- ↑ The Nama Karoo Biome. . Accessed 2 May 2014

- ↑ The Nama Karoo Biome . Accessed 2 May 2014