Kang bed-stove

The kang (Chinese: 炕; pinyin: kàng; Manchu: ![]() nahan, Kazakh: кән) is a traditional long (2 metres or more) platform for general living, working, entertaining and sleeping used in northern part of China, where there is cold climate in winter times. It is made of bricks or other forms of fired clay and more recently of concrete in some locations.

nahan, Kazakh: кән) is a traditional long (2 metres or more) platform for general living, working, entertaining and sleeping used in northern part of China, where there is cold climate in winter times. It is made of bricks or other forms of fired clay and more recently of concrete in some locations.

Its interior cavity, leading to a often convoluted flue system, channels the hot exhaust from a firewood/coal fireplace, usually the cooking fire from an adjacent room that serves as a kitchen, sometimes from a stove set below floor level. This allows a longer contact time between the exhaust (which still contains much heat from the combustion source) and (indirectly) the inside of the room, hence more heat transfer/recycling back into the room, effectively making it a ducted heating system similar to the hypocaust system used by ancient Romans. A separate stove may be used for controlling the amount of smoke circulating through the kang, maintaining comfort in warmer weather. Typically, a kang occupies one-third to one half the area the room, and is used for sleeping at night and for other activities during the day.[1] A kang which covers the entire floor is called a dikang (Chinese: 地炕; pinyin: dì kàng; literally: "ground kang").[1]

Like the European ceramic stove, a massive block of masonry is used to retain heat. While it might take several hours of heating to reach the desired surface temperature, a properly designed bed raised to sufficient temperature should remain warm throughout the night without the need to maintain a fire.

History

The kang is said to be derived from the concept of a heated bed floor called a huoqiang found in China in the Neolithic period, according to analysis of archeological excavations of building remains in Banpo Xi'an. However, archeological sites in Shenyang, Liaoning, show humans using the heated bed floor as early as 7,200 years ago.[2][3] The bed at this excavation is made of 10 cm pounded clay on the floor. The bed was heated by zhidi which is simply the process of placing an open fire on the bed floor and clearing the ashes before sleeping. It is mentioned by Tang poet Meng Jiao in his poem titled Handi Baixing Yin. 'No fuel to heat the floor to sleep, standing and crying with cold at midnight instead'. In the excavated example the repeated burning is believed to have turned the bed surface hard and moisture resistant.

The first known type of heated platform appeared in modern-day Northeast of China and used a single flue systems found in the hypocaust of Ancient Rome and the ondol of Korean origin.[3] An example of this type of heated platform was unearthed in 1st-century building remains in the Heilongjiang Province. Its single flue is 'L' shaped, built from adobe and cobblestones and covered with stone slabs.

Heated walls with a double flue system was found in a 4th-century ancient palace building in the Jilin Province. It has an 'L' shaped adobe bench with a double flue system. It is structurally more complex than a single flue system and has functionality similar to a kang.

The word kang means "to dry", first documented in the Chinese dictionary in AD121. The earliest kang remains have been discovered at Ninghai, Heilongjiang Province, in the Longquanfu Palace (699-926) of Balhae origin.

The kang may have evolved to its bed design from earlier developments due to ongoing cultural changes during the Southern and Northern Dynasties, as high furniture and chairs came to be prevalent, over the earlier style of floor-sitting and low-lying furniture in Chinese culture.[1]

Literary evidence from the Shui Jing Zhu also gives evidence of heated floors by the Northern Wei Dynasty, though it was not explicitly named a dikang:[1]

In Guanji Temple [near the present day Fengrun in Hebei province], there is a grand lecture hall. It is very high and wide to accommodate a thousand monks. The platform of the hall was constructed with stones arranged as a network of channels, and the floor was finished with a coat of clay. Fires are set at outdoor openings at the four sides of the platform, while the heat flows inwards warming the entire hall. The construction was established by a benefactor (or benefactors) to enable the monks to study in cold winters.

Outside China, the concept of a "masonry heater", a large stove made of brick or other masonry keeping a house warm for a long time, has been used in various forms throughout northern and eastern Europe. In particular, Russians have traditionally used a similar sort of stove/bed, known as the Russian oven (Russian: Русская печь); it is unknown whether this was introduced from the East during the period of the "Tatar yoke".

Culture

Traditional Chinese Dwellings (Zhongguo chuantong minju) (a bilingual text) has a few line drawings of kangs. It says that the kang is used to cook meals and heat the room, making full use of the heat-retaining capacity of the loess [soil used to make adobe]. The kang produces radiant heat to heat the interior space indirectly in addition to the bed mass itself. It has been speculated that one of the oldest forms of Chinese housing, heated cave dwellings known as yaodong, widespread throughout northern China would have been uninhabitable without the kang.[1]

The Kang was also an important feature of traditional dwellings in the often frigid northeastern region of Manchuria, where it was known as nahan in the native language of the local Manchus. It plays an important role in Manchu's mourning customs. The deceased is placed beside the Kang instead of the Han Chinese practice which is in the central hall. The height of the board on which the body is placed indicates the family status or age of the deceased.

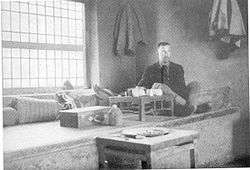

In this picture of a room in a Chinese inn, reproduced from Wandering in Northern China, by Harry A. Franck (Copyright 1923 by the Century Company of New York City and London), one can see a man who may be the author sitting at a short-legged table that has been placed on the Kang. Behind the Kang is a fine window that lets much light into the room. The window appears to be closed by a paper-covered lattice, not a pane of glass.

See also

- Masonry heater

- Ondol - similar system in Korea

- Kotatsu

- Russian oven

- Hypocaust

- Underfloor heating

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Guo, Qinghua (2002). "The Chinese Domestic Architectural Heating System [Kang]: Origins, Applications and Techniques". Architectural History. SAHGB Publications Limited. 45: 32–48. JSTOR 1568775.

- ↑ http://www.healthyheating.com/History_of_Radiant_Heating_and_Cooling/History_of_Radiant_Heating_and_Cooling_Part_1.pdf

- 1 2 Zhuang, Zhi; Li, Yuguo; Chen, Bin; Jiye; Guo (2009), "Chinese kang as a domestic heating system in rural northern China—A review", Energy and Buildings, 41 (1): 111–119, doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2008.07.013

- Bernan, Walter (1845) On the History and Art of Warming and Ventilating Rooms and Buildings by Open Fires, Hypocausts ... Stoves ... and Other Methods; with notices of the progress of personal and fireside comfort, and of the management of fuel. Illustrated by two hundred and forty figures of apparatus. 2 vols. London: George Bell, 1845 (Walter Bernan = Robert Stuart Meikleham)

- 1845 book

- 2001 book

- Chan, Alan, et al. (eds.) (2001) Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine. Singapore: World Scientific (Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on the History of Science in East Asia, held August 23–27, 1999 in Singapore)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kang (heated bed). |

- Mud bed influences Chinese ancient culture

- Robert Bean, Bjarne W. Olesen, Kwang Woo Kim, History of Radiant Heating and Cooling Systems. ASHRAE Journal, January 2010