Kanesatake, Quebec

| Kanehsatà:ke | |

|---|---|

| Mohawk Territory | |

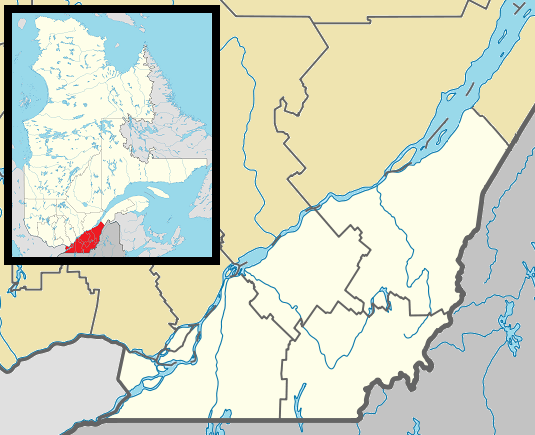

Location within Deux-Montagnes RCM. | |

Kanehsatà:ke Location in southern Quebec. | |

| Coordinates: 45°29′N 74°07′W / 45.483°N 74.117°WCoordinates: 45°29′N 74°07′W / 45.483°N 74.117°W[1] | |

| Country |

|

| Province |

|

| Region | Laurentides |

| RCM | Deux-Montagnes |

| Government | |

| • Grand Chief | Serge Otsi Simon |

| • Federal riding | Argenteuil—Papineau—Mirabel |

| • Prov. riding | Mirabel |

| Area[2] | |

| • Land | 11.88 km2 (4.59 sq mi) |

| Population (2014)[2] | |

| • Total | ~1,350 living on territory; 2,400 registered[3] |

| Time zone | EST (UTC−5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−4) |

Kanehsatà:ke is a Kanien'kéha:ka Mohawk settlement on the shore of the Lake of Two Mountains in southwestern Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers and about 30 miles west of Montreal. People who reside in Kanehsatà:ke are referred to as Kanehsatà:kehró:non. As of 2014, the total registered population was 2400, with a total of ~1350 persons living on the Territory. Both they and the Kanien'kéha:ka of the Kahnawà:ke reserve, located across from Montreal, also control and have hunting and fishing rights to Tiowéro:ton (aka Doncaster 17 Indian Reserve).[4]

The Kanien'kéha:ka historically were the most easterly nation of the Haudenosaunee (Six Nations Iroquois), who were based mostly east and south of the Great Lakes, in present-day New York west of the Hudson River, and in Pennsylvania of the United States, with hunting territory extending into the Ohio and Shenandoah valleys.

Some Mohawk moved closer for trade with French colonists in what became Quebec, Canada, or settled in mission villages. In the mid-nineteenth centuries, the people of Kanehsatà:ke were formally recognized as one of the Seven Nations of Canada, First Nations who were allies of the British. Today this territory, an interim land base, is one of several settlements or reserves in Canada where the Kanienkehaka are self-governing. Reserves include Kahnawake and Akwesasne along the St. Lawrence River, and the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation, where the Mohawk constitute the majority of residents.

History

Beginning about 1000AD indigenous people around the Great Lakes area began adopting the cultivation of maize. By the 14th century, Iroquoian-speaking peoples, later called the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, had created fortified villages along the fertile valley of what is now called the St. Lawrence River. They spoke a discrete Laurentian language.[5] Among their villages were Stadacona and Hochelaga, visited in 1535-1536 by explorer Jacques Cartier.

By the time Samuel de Champlain explored the same area 75 years later, the villages had disappeared. Huron and Kanienkehaka based in other Iroquoian territories used the valley for hunting grounds and routes for war parties. Historians are continuing to examine this culture, but theorize that the stronger Kanienkehaka (Mohawk) waged war against the St. Lawrence Iroquoians to get control of the fur trade and hunting along the valley downriver from Tadoussac. (The Montagnais, an Innu people, controlled Tadoussac, which was closer to the coast.)

By 1600, the Mohawk of the Iroquois Confederacy, based largely in present-day New York and Pennsylvania south of the Great Lakes, used the valley for hunting grounds. The Mohawk were the easternmost of the Five Nations.[5] While the Mohawk shared certain culture with the earlier Iroquoian groups, archeological and linguistic studies since the 1950s have demonstrated that the Mohawk and St. Lawrence Iroquoians were distinctly separate peoples.[5] Historians and anthropologists believe the Mohawk pushed out or destroyed the St. Lawrence Iroquoians.[5]

In the colonial period, the French established trading posts and missions with the Mohawk. They also had intermittent conflict and raiding. Some Mohawk moved near or in Montreal for trading and protection at mission villages. In 1717, the King of France granted the Mohawk in Quebec a tract of land 9 miles long by 9 miles wide about 40 miles to the northwest under the condition they leave the island of Montreal. The settlement of Kanesatake was formally founded as a Catholic mission, a seigneury under the supervision of the Sulpician Order for Mohawk, Algonquin, and Nipissing peoples in their care. Over time the Sulpicians claimed total control of the land, gaining a deed giving them legal title, when the Mohawk thought it was held in trust for them.[6][7]

A majority of the Mohawk converted to the Catholic religion during the colonial period, but grew wary of the Sulpicians due to mistreatment and unjust dealings with regard to their right to the land. The Sulpicians sold some of it for settlement, and the village of Oka developed around Kanesatake. In 1787 Chief Aughneeta complained by letter to Sir John Johnson, the superintendent general of Indian affairs, that the Mohawk had moved to Kanesatake only after being promised a deed to the land by the King of France.[6]

By 1851, the Mohawk made seven other protests about the land to the government. Mohawk dissent increased, and conversion to Protestantism in 1851 was avoided only when the Sulpicians excommunicated 15 activists.[6] In 1868 the Mohawk selected Sosé Onasakenrat as chief at the age of 22. Baptized as Joseph, he had been educated by the Sulpicians in a Catholic seminary and worked with them afterward at Oka. That year he traveled to Montreal to present the Mohawk land claim to the seigneury, but to no avail. Later that year, he and many other Mohawk converted to Methodism, as they were outraged by their treatment by the Catholic Church.[6]

In 1880 Onasakenrat was ordained and became a Methodist missionary to the Mohawk-dominated communities at Kahnawake and Akwesasne, which became known as First Nations reserves. He began to urge moderation and acceptance of a Sulpician offer to buy land for the Mohawk away from Oka and pay for their move. He lost the support of many followers by this change in position and died at age 35 in 1881. Six months later, when the Sulpicians had completed arrangements for the move, only 20 percent of the Mohawk left Kanehsatà:ke to relocate to present-day Wahta Mohawk Territory near Muskoka, Ontario.[6] In 1910 the Sulpician Order claim to the land was upheld by the Canadian Supreme Court. Kanesatake has been defined as an 'interim land base' by the federal government, unlike the reserves which come under the 20th-century Indian Act.

In terms of governance, the Mohawk at Kanehsatà:ke continued "custom", or the traditional practice of having clan mothers select chiefs from clans with hereditary responsibility; clan mothers made the selection. Like the other Iroquois nations and many other Native Americans, they long had a matrilineal kinship system, with inheritance and property passed through the maternal line.

In the late 20th century, the Kanienkehaka renewed a land claim case to recover their property at Kanesatake, but were ruled against by the courts on technical issues.[7] The settlement is surrounded by the city of Oka, Quebec. In 2001 S-24 was passed by the Parliament, to clarify the relationship between Kanesatake and the federal government, and make its relationship with provincial and federal governments comparable to those of the governments of reserves.[8] Different members of the community have disputed the interpretation of the intent and implementation of this act, and disagreements added to internal tensions.

History since 1990

Oka crisis

The City of Oka developed along the lake around the reserve of Kanehsatà:ke. The Sulpician order had sold off land to other settlers. The Mohawk had been contesting the Sulpician land claim since 1717, arguing that France never owned the land and thus France did not have the right to give the land to the Sulpician.[9] Included in these lands were a pine grove and cemetery long used by the Mohawk. Some of their ancestors' tombstones were still standing in the cemetery. The Mohawk had tried to reclaim this land (as part of their land claim against the government and Sulpician mission) but were rejected in the courts due to technical issues.

In 1990 the City of Oka approved plans to develop the pine grove and cemetery by allowing the addition of nine holes to a private golf course, along with construction of new private luxury housing. The Mohawk protested formally, because they considered the land to be sacred. The city persisted in letting the developer proceed. In response, the Mohawk barricaded a dirt road leading to the land to prevent the developer's vehicles from passing.[7] This was the beginning of a 78-day standoff between the Mohawk Nation and their allies (both aboriginal and non-aboriginal) against various levels of local and Canadian government.

The city requested support from the Sûreté du Québec, who barricaded highway 344 leading to Kanesatà:ke. In the first days of the confrontation, a police officer was killed in an exchange of gunfire with the protesters. In solidarity, Mohawk in Kahnawake blockaded the approach to the Mercier Bridge over the St. Lawrence River; this route passed through their land. Non-Mohawk residents of the area became enraged about traffic delays in trying to get through this area and across the river.

The Quebec provincial government requested support from the Canadian Army, which sent in 3700 troops.[10] Provincial and national leaders participated in negotiations between the Mohawk and the provincial government. The Mohawk at Kanesatà:ke finally removed their barricades.[7] Police and military forces pushed the remaining protesters back until they were confined to the health centre and surrounded by the military. The protesters' food and supply lines were systematically reduced and possibly tampered with.

In the end they chose to come out of the health centre, although they did not formally surrender.[7] They were immediately arrested and separated. These events and history are explored in Alanis Obomsawin's documentary film, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993). A number of Mohawk were tried and convicted, and disruption continued.

Electoral changes

In 1991 the people adopted an electoral political system for the first time (see Governance below). Because they do not come under the Indian Act, their choice was still considered "custom". There has continued to be internal division over how chiefs are selected. In the first election, Jerry Peltier was elected as Grand Chief, serving two terms into 1996.

In 2013 the Kanehsatà:ke Health Centre Inc. was the first Indigenous Health Centre in North America to receive a Baby Friendly Accreditation, a major achievement.

Also in 2013 the local Pikwadin group, a funded initiative of the First Nations Human Resource and Development Commission of Quebec (FNHRDCQ), began a re-vamp of the local radio station CKHQ 101.7 FM. It had become idle after its previous manager died in 2003. In 2004 the station failed to renew its broadcasting licence with the CRTC. The radio station was running under a 'pirate radio' status pending a licence renewal, until it was accepted on June 17, 2014.[11][12] The Montréal-based non-profit organization Exeko assisted with the licensing process through their idAction program [13]

Governance

The Oka crisis generated political change at Kanehsatà:ke. They altered their method of governance. In 1991 their citizens held the first elections for grand chief and six council chiefs. Chiefs previously had traditional hereditary claims to positions through their clans under the matrilineal kinship system, in which inheritance and property were passed through the maternal lines. Chiefs were nominated (and could be unseated) by clan mothers. In 1991 Jerry Peltier was elected as grand chief, serving until 1996.[14] He also served as Chairman for the Quebec First Nations Education Council.[15]

In the 1990s, the Nation began to exercise more autonomy, establishing its own police force.[16]

In 2004 and 2005, disputes over the governance practices of Grand Chief James Gabriel, who had been elected three times to his position, resulted in violence and political disruption in Kanehsatà:ke. Chiefs Pearl Bonspille, Steven Bonspille and John Harding (Sha ko hen the tha) opposed Gabriel. They and other opponents effectively ended Gabriel's tenure as grand chief.

John Harding and fellow council chiefs Steven Bonspille (who was elected to the council in 2001) and Pearl Bonspille said they opposed Gabriel's attempt to control policing by bringing in more than 60 officers from other reserves and forces for a drug raid in January 2004. (He had support from the Quebec Sûreté.) These chiefs, dissidents, considered Gabriel's action to be an unlawful attempt to usurp the power of the Police Commission. The 67 special constables were forced to take shelter in the local police station for protection after 200 community members surrounded the police station. After Gabriel's home was burned in purported arson, the deposed chief left the community for Montreal.[14][16] "A long criminal trial resulted in multiple convictions of Kanesatake residents for arson, rioting and other offences."[14]

During this period, the reserve organized a Community Watch team to counter the lack of a police force. A liaison team was established with the Sûreté du Québec (the provincial police force). Political communication lines were opened up with the Quebec government to prevent another crisis as had occurred in 1990 at Oka.

Following the overthrow of Gabriel, elections were held in late spring of 2005. On June 26, 2005, Steven Bonspille defeated Gabriel in the election for grand chief. But Harding and Pearl Bonspille were both replaced as chiefs on the council when a slate of six Gabriel allies were elected.[14] For a period the Nation operated under a federal trusteeship as an investigation was made of alleged spending excesses under Gabriel, but it was not conclusive.[14]

Tribal engagement in politics has remained high: in 2008 there were 25 candidates running for seven seats on the council. Steven Bonspille chose not to run for re-election and had moved off the reserve to Oka to get some distance. At the time, there were more than 2300 voters registered: 1685 on the reserve territory and 664 outside.[14]

As of 2015, the grand chief of Kanesatake is Serge Simon. Soon after his election, he spoke in an interview with the Montreal Gazette about events from the Oka Crisis in 1990.[17]

Tobacco trade

Tobacco is a traditional herb and medicine indigenous to North and South America. Archeological evidence has shown its use has been part of ritual religious and political traditions in native cultures in the Americas for at least two thousand years. Under current laws in Canada and the United States, state and provincial authorities attempt to control commercial sales of tobacco products through prices and sales taxes, in part because of health concerns related to tobacco's ill effects if used in excess.

Kanehsatà:ke has benefited by economic returns from the tax-free sales of tobacco (in cigarettes) to non-natives. Beginning about 2003 with only two fishing shacks set up at each end of the territory, the community has expanded its tobacco sales. As of 2014 there are ~25 stores selling tobacco products. The Mohawk reserves of Akwesasne and Kahnawake have both developed factories to supply Kanehsatà:ke with their cigarettes since the business expansion began.

Through the available historical archives from parish resisters available from 1721 to 1800, on August 20 1789 a cultural notice concerning tobacco also known as "petun", which was the only one observed during the period analysed read like this: "Michel, borned on the 26th of July, illegitimate child of Marguerite St-Germain (who was buried the 24th of August.) The godfather was Ignace “Kit8eiantch” and the last sentence read: “ne trouvant point d’autre petun et l’enfant en danger pressant” / “not finding any more petun and the child in urging danger”.(Eric Pouliot-Thisdale, 1786-1800 Oka Mission Parish registers Kanehsatà:ke,OKA, Library and Archives Canada, Montreal, 2015, page 103)

Education

The area English school board is the Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board. As of 2014, 55 students from Kanesatake choose to attend Lake of Two Mountains High School in Deux-Montagnes.[18] Mountainview Elementary School and Saint Jude Elementary School, both in Deux-Montagnes, also serve this community.[19][20]

See also

- Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, 1993 documentary by Alanis Obomsawin

- Joseph Onasakenrat, Chief of the Mohawk nation at Kanesatake, 1868–1881

References

- ↑ Reference number 149275 of the Commission de toponymie du Québec (French)

- 1 2 "(Code 2472802) Census Profile". 2011 census. Statistics Canada. 2012.

- ↑ "Mohawks of Kanehsatà:ke - Connectivity Profile", Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, accessed 11 September 2013

- ↑ "Mohawks of Kanesatake", Aboriginal Communities, Government of Canada

- 1 2 3 4 Pendergast, James F. (Winter 1998). "The Confusing Identities Attributed to Stadacona and Hochelaga". Journal of Canadian Studies. 32 (4): 149–159.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith, Donald B. (1982). "Onasakenrat Joseph". In Halpenny, Francess G. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. XI (1881–1890) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press., accessed 13 October 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alanis Obomsawin, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, National Film Board of Canada, 1993, accessed 30 January 2010

- ↑ "BILL S-24: THE KANESATAKE INTERIM LAND BASE GOVERNANCE ACT", Parliament, Canada

- ↑ http://commonground.ca/2013/05/oka-origin-of-a-crisis/

- ↑ [ Marian Scott, "Revisiting the Pines: Oka's legacy"], Montreal Gazette, 10 July 2015, accessed 13 October 205

- ↑ , CRTC

- ↑ "CRTC approves CKHQ licence", blog

- ↑ "Uniting Kanesatake through radio", Wawatay News, 16 May 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jeff Heinrich, "Wide-open race in Kanesatake", The Gazette, 27 June 2008, La Nation Autochthone du Quebec, accessed 29 January 2010

- ↑ "Jerry Peltier", ZoomInfo, accessed 13 October 2015

- 1 2 Aubin, Benoit (March 23, 2004). "Kanesatake Chief in Exile", Maclean's Magazine, online at The Canadian Encyclopedia, Retrieved on: July 12. 2008.

- ↑ Marian Scott, "Kanesatake chief remembers the chaos: 'They were out to kill' ", Montreal Gazette, 10 July 2015, accessed 13 October 2015

- ↑ "Overview." Lake of Two Mountains High School. Retrieved on December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Mountainview Elementary Zone." Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board. Retrieved on December 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Saint Jude Elementary School Zone Map," Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board. Retrieved on December 8, 2014.

Further reading

- Claude Pariseau, “Les troubles de 1860–1880 à Oka: choc de deux cultures” (thèse de MA, McGill Univ., 1974).

- J. K. Foran, “Chronique d’Oka,” Le Canada (Ottawa), 2, 10, 19, 22 juill., 3, 12, 19, 30 août, 9, 13 sept. 1918.

- Olivier Maurault, “Les vicissitudes d’une mission sauvage,” Rev. trimestrielle canadienne (Montréal), 16 (1930): 121–49.

External links

- Kanesatake First Nation, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada

- Native nations of Québec, Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones du Québec

- Photos, Surviving Canada

Links re: Policing and governance issues of 2003-2005

- Chronology 2003-2005 Kanesatake Mohawk Voice

- Ross Montour, "Impasse leads to trusteeship over Kanehsatake", The Eastern Door (Kahnawake Mohawk Community).

- "Mohawk blockade stops traffic near Kanesatake", CTV.ca

- Francis v. Mohawk Council of Kanesatake - Judicial review of Council decision re: 2003 By-election (Federal Court of Canada)

- Ross v. Mohawk Council of Kanesatake, Judicial review of Council decision to fire Ross (Federal Court of Canada)

- "Mohawks end blockade northwest of Montreal", Sympatico.ca

- "Uprising in Kanesatake", Maritimes Independent Media

|

Mirabel |  | ||

| Oka | |

Oka | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Oka |