Kafiristan

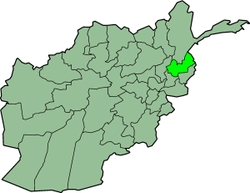

Kāfiristān or Kāfirstān (Pashto: کافرستان) is a historical region that covered present-day Nuristan Province in Afghanistan and its surroundings. It was also referred to as "Afica". This historic region lies on, and mainly comprises, the basins of the rivers Alingar, Pech (Kamah), Landai Sin, and Kunar, and the intervening mountain ranges. It is bounded by the main range of the Hindu Kush on the north, the city of Chitral in what is now Pakistan to the east, the Kunar Valley in the south, and the Alishang River in the west. Kafiristan took its name because the Nuristani inhabitants of the region, who once followed a form of ancient Hinduism, were non-Muslims and were thus known to the surrounding Muslim population as Kafir, meaning "infidel".[1] They are closely related to the Kalash people, a fiercely independent people with a distinctive culture, language and religion.

Etymology

Kafiristan or Kafirstan is normally taken to mean "land [-stan] of the kafirs" in Persian language, where the name kafir is derived from the Arabic kaafer, literally meaning a person who refuses to accept a principle of any nature and figuratively as a person refusing to accept Islam as his faith and is commonly translated into English as an "infidel" or "unbeliever".[1] Kafiristan was inhabited by people who followed a form of ancient Hinduism,[1] before large numbers converted to Islam in the 1890s.

The word "kafir" has also been suggested to be linked to Kapiś (= Kapish), the ancient Sanskrit name of the region that included historic Kafiristan. According to the theory, the name may have then mutated at some point into the word Kapir, and once again into the word Kafir.[2][3][4][5]

History of Kafiristan

Ancient history

Ancient Kapiśa janapada, located south-east of the Hindukush, included and is related to Kafiristan.[6] The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang who visited Kapisa in 644 AD calls it Kai-pi-shi(h).[7] Xuanzang describes Kai-pi-shi[8] as a flourishing kingdom ruled by a Buddhist kshatriya king holding sway over ten neighbouring states, including Lampaka, Nagarahara, Gandhara and Bannu. Until the 9th century AD, Kapiśi remained the second capital of the Shahi dynasty of Kabul. Kapiśa was known for goats and their skin.[9] Xuanzang talks of Shen breed of horses from Kapiśa (Kai-pi-shi). There is also a reference to Chinese emperor Taizong being presented with excellent breed of horses in 637 AD by an envoy from Chi-pin (Kapisa).[10] Further evidence from Xuanzang shows that Kai-pi-shi produced all kind of cereals, many kinds of fruits, and a scented root called yu-kin, probably of the grass khus, or vetiver. The people used woollen and fur clothes and gold,[11][12] silver and copper coins. Objects of merchandise from all parts were found here.[13]

Ghaznavids era

Another crusade against idolatry was at length resolved on; and Mahmud led the seventh one against Nardain, the then boundary of India, or the eastern part of the Hindu Kush; separating, as Ferishta says, the countries of Hindustan and Turkistan and remarkable for its excellent fruit. The country into which the army of Ghazni marched appears to have been the same as that now called Kafirstan, where the inhabitants were and still are, idolaters and are named the Siah-Posh, or black-vested, by the Muslims of later times. In Nardain there was a temple, which the army of Ghazni destroyed; and brought from thence a stone covered with certain inscriptions, which were according to the Hindus, of great antiquity.[14]

Early modern and later history

The first European recorded as having visited Kafiristan was the Portuguese Jesuit missionary Benedictus Gomes, SJ. By his account, he visited a city named "Capherstam"[15] in 1602, during the course of a journey from Lahore to China.[16]

The British adventurer Colonel Alexander Gardner claimed to have visited Kafiristan twice, in 1826 and 1828.[16] On the first occasion, Dost Mohammad, the amir of Kabul, killed members of Gardner's delegation in Afghanistan and forced him to flee from Kabul to Yarkand through west Kafiristan.[16] On his second visit, Gardner briefly sojourned in northern Kafiristan and the Kunar Valley while returning from Yarkand.[16]

George Scott Robertson, medical officer during the Second Anglo-Afghan War and later British political officer in the princely state of Chitral, was given permission to explore the country of the Kafirs in 1890–91. He was the last outsider to visit the area and observe these people's polytheistic culture before their conversion to Islam. Robertson's 1896 account was entitled The Kafirs of the Hindu Kush. Though some sub-groups such as the Kom paid tribute to Chitral, the majroity of Kafiristan was left on the Afghan side of the frontier in 1893, when large areas of tribal lands between Afghanistan and British India were divided into zones of control by the Durand Line.

A few years after Robertson’s visit, in 1895-6, Emir Abdur Rahman Khan invaded and converted the Kafirs to Islam as a symbolic climax to his campaigns to bring the country under a centralised Afghan government. He had similarly subjugated the Hazara people in 1892-3. In 1896 Abdur Rahman Khan, who had thus conquered the region for Islam,[17] renamed the people the Nuristani ("Enlightened Ones" in Persian) and the land as Nuristan ("Land of the Enlightened").

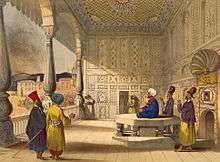

Kafiristan was full of steep and wooded valleys. It was famous for its precise wood carving, especially of cedar-wood pillars, carved doors, furniture (including "horn chairs") and statuary. Some of these pillars survive, as they were reused in mosques, but temples, shrines, and centers of local cults, with their wooden effigies and multitudes of ancestor figures were torched and burnt to the ground. Only a small fraction brought back to Kabul as spoils of this Islamic victory over infidels. These consisted of various wooden effigies of ancestral heroes and pre-Islamic commemorative chairs. Of the more than thirty wooden figures brought to Kabul in 1896 or shortly thereafter, fourteen went to the Kabul Museum and four to the Musée Guimet and the Musée de l'Homme located in Paris.[18] Those in the Kabul Museum were badly damaged under the Taliban but have since been restored.[19]

A few hundred Kati Kafirs, known the Red Kafirs of the Bashgal Valley, fled across the border into Chitral but, uprooted from their homeland, they converted by the 1930s. They settled near the frontier in the valleys of Rumbur, Bumboret and Urtsun, which were then inhabited by the Kalasha tribe or the Black Kafirs. Only this group in the three valleys of Birir, Bumburet and Rumbur escaped conversion, because they were located east of the Durand line in the princely state of Chitral. After a decline in population caused by forced conversion in the 1970s, this region of Kafiristan in Pakistan, known as Kalasha Desh, has recently shown an increase in its population.

Appearances in culture

- Kafiristan is the setting of most of Rudyard Kipling's famous 1888 novella "The Man Who Would Be King". It was adapted into the 1975 film of the same name.

- English travel writer Eric Newby's 1958 A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush describes the adventures of himself and Hugh Carless in Nuristan and their attempt at the (at the time) unprecedented feat of scaling the Mir Samir mountain.

- The Journey to Kafiristan is a German film by Donatello Dubini and Fosco Dubini.

See also

- Chiliss, an ancient people

- Chitrali people

- Kalash people

- Nuristani people

- Shin of Hindukush, a tribe

- Shina language

References

- 1 2 3 Minahan, James B. (10 February 2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 205. ISBN 9781610690188.

Living in the high mountain valleys, the Nuristani retained their ancient culture and their religion, a form of ancient Hinduism with many customs and rituals developed locally. Certain deities were revered only by one tribe or community, but one deity was universally worshipped by all Nuristani as the Creator, the Hindu god Yama Raja, called imr'o or imra by the Nuristani tribes. Around 700 CE, Arab invaders swept through the region now known as Afghanistan, destroying or forcibly converting the population to their new Islamic religion. Refugees from the invaders fled into the higher valleys to escape the onslaught. In their mountain strongholds, the Nuristani escaped conversion conversion to Islam and retained their ancient religion and culture. The surrounding Muslim peoples used the name Kafir, meaning "unbeliever" or "infidel," to describe the independent Nuristani tribes and called their highland homeland Kafiristan.

- ↑ Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, p 44, Dr Moti Chandra - India.

- ↑ Census of India, 1961, p 26, published by India Office of the Registrar General.

- ↑ See also: Kāṭhakasaṅkalanam: Saṃskr̥tagranthebhyaḥ saṅgr̥hītāni Kāṭhakabrāhmaṇa, Kāṭhakaśrautasūtra, 1981, p xii, Surya Kanta; cf: The Contemporary Review, Vol LXXII, July-Dec, 1897, p 869, A. Strahan (etc), London.

- ↑ S. Levi states that Chinese Kipin is a rendering of an Indian word Kapir (See quote in: Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, p 44, Moti Chandra - India; See also: Bhārata-kaumudī; Studies in Indology in Honour of Dr. Radha Kumud Mookerji, 1945, p 916, Radhakumud Mookerji - India).

- ↑ Ethnology of Ancient Bhārata, 1970, p 112, Dr R. C. Jain; Ethnic Settlements in Ancient India: (a Study on the Puranic Lists of the Peoples of Bharatavarsa, 1955, p 133, Dr S. B. Chaudhuri; The Cultural Heritage of India, 1936, p 151, Sri Ramakrishna Centenary Committee; Geography of the Mahabharata, 1986, p 198, Bhagwan Singh Suryavanshi.

- ↑ Another Chinese name for this region was Ki-pin or Chi-pin.

- ↑ Su-kao-seng-chaun, Chapter 2, (no. 1493); Kai-yuan-lu, chapter 7; Publications, 1904, p 122-123, published by Oriental Translation Fund (Editors Dr T. W. Rhys Davis, S. W. Bushel, London, Royal Asiatic Society).

- ↑ Geography of the Mahabharata, 1986, p 183, B. S.Suryavanshi.

- ↑ See:: T'se-fu-yuan-kuei, p 5024; Wen hisen t'ung-k'ao, 337: 45a; Diplomacy and Trade in the Chinese World, 589–1276, 2005, P 345, Hans Bielenstein

- ↑ Corpus II. 1, xxiv; Cambridge History of India, Vol i\I, p 587.

- ↑ Ancient references like Mahabharata, Ramayana etc profusely attest that the Kambojas produced and made use of woollen, fur and skin clothes and shawls, all embroidered with gold. Ancient Kambojas were noted for their horses, gold, woollen blankets, furry clothing etc (Foundations of Indian Culture, 1990, p 20, Dr Govind Chandra Pande – Spiritualism (Philosophy); Hindu World, Volume I, 1968, p 520, Benjamin Walker etc

- ↑ Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, 1906, p 54 & fn, By Samuel Beal.

- ↑ K̲h̲ān̲, ʻAlī Muḥammad (1835). The Political and Statistical History of Gujarát. Translated by Bird, James. London: Richard Bentley. p. 29.

- ↑ Pieter Vander Aa. "De Land-Reyse, door Benedictus Goes, van Lahor gedaan, door Tartaryen na China". Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps.

- 1 2 3 4 Newby, Eric. "A little bit of protocol". A short walk in the Hindukush. Picador India. pp. 74–93. ISBN 978-0-330-46267-9.

- ↑ Tanner, Stephen. Afghanistan: A Military History from Alexander the Great to the Fall of the Taliban. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002. Page 64

- ↑ Edelberg, Lennart. "Statues de bois rapporte‚ es du Kafiristan aà Kabul apreàs la conquête de cette province par l'Emir Abdul Rahman en 1895/96," Arts Asiatiques 7, 1960, pp. 243–286

- ↑ "R20405 KAkir sculpture from Nuristan destroyed by the talibans then restored". reportages-pictures.com.

- Greg, Mortenson. Stones into Schools. Penguin Books, 2009; p. 259

External links

-

"Kafiristan". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Kafiristan". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. - Map of Kafiristan 1881. Contributors Royal Geographical Society (great Britain)