Josef Mysliveček

Josef Mysliveček (9 March 1737 – 4 February 1781) was a Czech composer who contributed to the formation of late eighteenth-century classicism in music. Mysliveček provided his younger friend Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with significant compositional models in the genres of symphony, Italian serious opera, and violin concerto; both Wolfgang and his father Leopold Mozart considered him an intimate friend from the time of their first meetings in Bologna in 1770 until he betrayed their trust over the promise of an operatic commission for Wolfgang to be arranged with the management of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. He was close to the Mozart family, and there are frequent references to him in the Mozart correspondence.

Biography

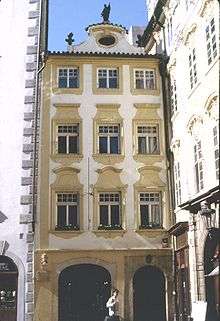

Mysliveček was born in Prague, one of twin sons of a prosperous mill owner, and studied philosophy at Charles-Ferdinand University before following in the footsteps of his father.[1] No documentation exists to support claims that he was actually born in Horní Šárka, a rural district to the north and west of Prague in the early eighteenth century. He achieved the rank of master miller in 1761, but gave up the family profession in order to pursue musical studies. In Prague, he studied composition with Franz Habermann and Josef Seger in the early 1760s. His ambitions led him to travel to Venice in 1763 to study with Giovanni Pescetti. His travel to Italy was subsidized in part from family wealth, in part from the Bohemian nobleman Vincenz von Waldstein. In Italy he became known as Il Boemo ("the Bohemian") and also Venatorini ("the little hunter"), a literal translation of his name. Reports that he was known as Il divino Boemo ("the Divine Bohemian") during his lifetime are false.[2] The nickname originated from the title of a romanetto about the composer by Jakub Arbes that was first published in 1884. He was made a member of the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna in 1771. Mysliveček prized freedom of movement and was never employed directly by any noble, prelate, or ruler, unlike most of his contemporaries. He earned his living through teaching, performing, and composing music, and frequently received gratuities from wealthy admirers. Financially irresponsible throughout his life, he died destitute in Rome in 1781. He is buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina, where a memorial placed by latter-day Czech admirers can be seen. No trace has ever been found of a memorial in marble supposedly erected shortly after his death by James Hugh Smith Barry, a wealthy English student of Mysliveček who paid for his funeral expenses.

After his arrival in Italy in 1763, Mysliveček never left the country except for a visit to Prague in 1767–68, a short visit to Vienna in 1773, and an extended stay in Munich between December 1776 and April 1778. His return to Prague led to the production of several of his operas. He was invited to Munich by the musical establishment of the Elector Maximilian III Joseph to compose an opera for the carnival season of 1777 (Ezio).

Mysliveček's first opera, Semiramide, was performed at Bergamo in 1766 (there is no evidence that a putative production at Parma of an opera titled Medea ever took place). His Il Bellerofonte was a great success in Naples after its first performance at the Teatro San Carlo on 20 January 1767, and it led to a number of commissions from Italian theaters. Ever after, his productions would almost always feature first-rate singers in the leading roles. Almost all of his operas were successful until a disastrous production of Armida that took place at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan for the carnival season of 1780. One of the many honors that came to him for his talents as a composer of opera was a commission to provide the music for the opening of a new opera theater in Pavia in 1773 (his first setting of Metastasio's libretto Demetrio).[3]

Other than a reputation for promiscuity recorded in the Mozart correspondence, nothing is known of Mysliveček's love life. The composer never married, and no names of lovers are recorded. There is no documentation to support reports of romantic liaisons with the singers Caterina Gabrielli and Lucrezia Aguiari; no mention of love affairs with these singers pre-dates the publication of the fifth edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1954).

Relationship with Mozart

In 1770 Mysliveček met the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Bologna.[4] He was close to the Mozart family until 1778, when contacts were broken off after he failed to make good on a promise to arrange an opera commission for Mozart at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples.[5] Earlier, the Mozarts found his dynamic personality irresistible. In a letter to his father Leopold written from Munich on 11 October 1777, Mozart described his character as "full of fire, spirit and life."

Similarities in his musical style with the earlier works of Mozart have often been noted. Additionally, Mozart used musical motives drawn from various Mysliveček compositions to help fashion opera arias, symphonic movements, keyboard sonatas, and concertos. He also made an arrangement of Mysliveček's aria "Il caro mio bene" (from the opera Armida of 1780). The old text was replaced with the new text "Ridente la calma", KV 152 (210a), in a scoring for soprano with piano accompaniment.

According to the same letter of Wolfgang Mozart written from Munich on 11 October 1777, an incompetent surgeon burned off Mysliveček's nose while trying to treat a mysterious illness.[6] A letter of Leopold Mozart to his son of 1 October 1777 refers to the illness as something shameful for which Mysliveček was deserving of social ostracism. Mysliveček's reputation for sexual promiscuity, Leopold's insinuations, and the reference to facial disfigurement in Wolfgang's letter hint unmistakenly at the symptoms of tertiary syphilis. Mysliveček's explanation for his condition to Wolfgang--bone cancer caused by a carriage accident—is on the face of it preposterous. The concern Mozart revealed to his father at this time for Mysliveček's sufferings was very touching. In the entire Mozart correspondence, no individual outside the Mozart family was ever the cause for so much outpouring of emotion as what is found in Wolfgang's letter of 11 October 1777.

Compositions

In all, he wrote twenty-six opere serie, including the aforementioned Il Bellerofonte. Nearly all were successful at their first performances until the disaster of Armida at La Scala during carnival of 1780. Some of the irregularities that doomed this production were not Mysliveček's fault, however, for example the interruption of performances caused by the lying-in of the prima donna Caterina Gabrielli, who gave birth, out of wedlock, in the middle of the run, at the age of 49.[7]

During the period of his activity as a composer of operas (1766–1780), Mysliveček succeeded in having more new opere serie brought into production than any other composer in Europe. It is noteworthy that in this same period more of his works were performed at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, the most prestigious venue in Italy at that time for productions of serious opera, than those of any other composer. Nonetheless his contributions to Italian operatic culture of the 1760s and 1770s have been almost universally ignored by opera historians.

Mysliveček and Gluck were the first Czechs to become famous as operatic composers, but their output exhibits few, if any, Czech characteristics. Mysliveček's operas were very much rooted in a style of Italian opera seria that prized above all the vocal artistry to be found in elaborate arias.

Among his other pieces were oratorios, symphonies, concertos, and chamber music, including some of the earliest known string quintets composed with two violas. His Op. 2 string quintets were almost certainly the earliest string quintets with two violas ever published. Additionally, he was a pioneer in the composition of music for wind ensemble, the outstanding examples of which are his three wind octets. It may be fair to say that his greatest composition is the oratorio Isacco figura del Redentore, first performed in Florence in 1776. His violin concertos are perhaps the finest composed between the generation of Vivaldi and the Mozart violin concertos of 1775.

He was also one of the most gifted and most prolific composers of eighteenth-century symphonies, although his contributions to this genre have been ignored by musicologists in western Europe and North America almost as completely as his operas have been. Nearly all of Mysliveček's symphonies are cast in three movements without a minuet, following Italian traditions that originated in opera overtures. His opera overtures are also cast in three movements and were frequently performed as independent instrumental pieces. In the 1770s, he was the finest symphonist resident in Italy, and the esteem he enjoyed is reflected in the issuance of a set of symphonies (originally opera overtures) published by Ranieri del Vivo in Florence that was the first anthology of symphonies ever printed in Italy.

Mysliveček's compositions evoke a gracious, diatonic style typical of Italian classicism in music. His best works are characterized by melodic inventiveness, logical continuity, and a certain emotional intensity that may be attributable to his dynamic personality.

Works

Instrumental works

Mysliveček's instrumental music includes divertimenti, sonatas, symphonies, etc.[8] Lost and questionable works have been omitted from this works' list, however they are inventoried fully in Freeman, Josef Mysliveček, which also provides a complete list of recordings and early and modern editions of the composer's music. The listings here do not report all manuscript and printed sources, rather key eighteenth-century sources and catalogs that offer clues to chronology.

Works for solo keyboard

- Six Easy Divertimentos for the Harpsichord or Piano-Forte. London: Longman & Broderip, 1777. [F major, A major, D major, B-flat major, G major, C major]

- Six Easy Lessons for the Harpsichord. Edinburgh: Corri & Sutherland, 1784. [C major, B-flat major, A major, G major, F major, D major]

- 1 undated sonata in C major in the Archivio e Museo della Badia of the Basilica Benedettina di San Pietro, Perugia

Violin sonatas

- 5 sonatas for violin and a bass line preserved in manuscripts in the library of the Conservatorio di Musica Niccolò Paganini in Genoa, perhaps from the 1760s

- Six Sonatas for the Piano Forte or Harpsichord with an Accompaniment for a Violin. London: Charles & Samuel Thompson, c. 1775. [E-flat major, D major, C major, B-flat major, G major, F major]

- 6 sonatas for violin and keyboard in a manuscript dated 1777 in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague [D major, F major, E-flat major, G major, B-flat major, E-flat major]

- 6 sonatas for violin and keyboard in an undated manuscript in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague [D major, G major, C major, B-flat major, F major, C major]

Sonatas for two cellos

- 6 sonatas for two cellos and a bass line in an undated manuscript in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague [A major, D major, G major, F major, C major, B-flat major]

Sonata for violin, cello, and bass

- 1 sonata in G major for violin, cello, and a bass line in an undated manuscript in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague

Duets for two flutes

- 6 duets for two flutes and a bass line in an undated manuscript in the private collection of Antonio Venturi in Montecatini-Terme, Italy [G major, C major, A minor, E minor, D major, B-flat major]

Trios for flute, violin, and cello

- Sei trii per flauto, violino, e violoncello. Florence: Del Vivo, c. 1778 [D major, G major, C major, A major, F major, B-flat major]

String trios

- 1 trio for 2 violins and cello in E-flat major in the Music Library of the University of California at Berkeley (remnant of a set of six advertised in the Breitkopf catalog of 1767)

- Six sonates, op. 1, for 2 violins and cello published by La Chevardière in Paris c. 1768 [C major, A major, D major, F major, A major, E-flat major]

- Four of the trios in the Op. 1 set of La Chevardière also appear in Six Orchestra Trios for Two Violins and a Violoncello (London: Welcker, c. 1772), but the English print also contains two new trios [G major, B-flat major]

- Six sonates, op. 1, for 2 violins and cello published by La Menu in Paris in 1772 [C major, G major, E-flat major, A major, B-flat major, F major]

- 5 additional trios for 2 violins and cello survive in undated manuscripts in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague [D major, F major, F major, G major, A major]

- 1 additional trio in E major for 2 violins and cello (remnant of an original set of six) survives in the Biblioteca Antoniana in Padua

Trio for violin, cello, and string bass

- 1 trio in G major for this combination of instruments survives in the České Muzeum Hudby

String quartets

- Sei quartetti a due violini alto e basso, op. 3. Paris: La Chervardière; Lyon: Castaud, c. 1768. [A major, F major, B-flat major, G major, E-flat major, C major]

- Sei quartetti a due violini, viola e violoncello, op. 1. Offenbach: Johann André, 1777. [E-flat major, C major, D major, F major, B-flat major, G major]

- Six quatuors à deux violons, taille et basse, op. post. Berlin: Hummel, c. 1781.

String quintets

- VI Sinfonie concertanti o sia quintetti per due violini, due viole, e basso, Op. 2. Paris: Venier; Lyon: Castaud, c. 1767. [B-flat major, E major, G major, A major, D major, C major]

- 6 string quintets in an undated manuscript in the Biblioteca Estense in Modena [G major, E-flat major, C major, A major, F major, B-flat major]

Wind quintets

- 6 quintets for 2 oboes, 2 horns, and bassoon in undated manuscripts in the Santini-Bibliothek in Münster, probably composed in Rome in 1780 or 1781 [D major, G major, E-flat major, B-flat major, F major, C major]

Wind octets

- 3 octets for 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 horns, and 2 bassoons in undated manuscripts from the Fürstlich Fürstenburgische Hofbibliothek in Donaueschingen, probably composed in Munich in 1777 or 1778 [E-flat major, E-flat major, B-flat major]

Oboe quintets

- 6 quintets for oboe with string quartet in an undated manuscript in the Biblioteca Comunale in Treviso [B-flat major, D major, F major, C major, A major, E-flat major]

Miscellaneous work for wind instruments

- "Cassation" for 2 clarinets & horn in B flat major in an undated manuscript in the Rossijskaja Nacional'naja Biblioteka in St. Petersburg

Concertos

- Violin Concerto in D major cited in the Breitkopf catalog of 1769, preserved in an undated manuscript in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague

- Violin Concerto in C major cited in the Breitkopf catalog of 1770, preserved in an undated manuscript in the Thüringesches Hauptstaatsarchiv in Weimar, the original version of the Cello Concerto in C major

- Violin Concerto in C major preserved in an undated manuscripts in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague and other archives

- Six violin concertos preserved in an undated manuscript in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, almost certainly composed by 1772 [E major, A major, F major, B-flat major, D major, G major]

- Cello Concerto in C major preserved in an undated manuscript in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, an arrangement of a violin concerto preserved in Weimar

- Flute Concerto in D major preserved in an undated manuscript in the Biblioteka Uniwersytecka in Wrocław

- 2 Keyboard Concertos preserved in undated manuscripts in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris

- 3 concertos for wind quintet & orchestra in undated manuscripts in the library of the Monumento Nazionale di Montecassino

Symphonies

- No. 1 - Symphony in C major dated 1762 in a manuscript preserved in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague

- Nos. 2-7 – Six symphonies [D major, G major, C major, D major, G minor, D major] preserved in the print VI Sinfonie a quattro, Op. 1 (Nuremberg: Johann Ulrich Haffner, [c. 1763])

- No. 8 – Symphony in D major cited in a 1766 catalog of the musical holdings of the court of Sigmaringen

- Nos. 9-10 – Two symphonies [G major, D major] cited in a 1768 catalog of the musical holdings of the Benedictine monastery of Lambach

- Nos. 11-12 – Two symphonies [D major, E-flat major] offered for sale in the Breitkopf catalog of 1769

- No. 13 – Symphony in D major dated 1769 in a manuscript in the Moravské Zemské Muzeum in Brno

- No. 14 – Symphony in G major dated 1770 in a catalog of the musical holdings of the Benedictine monastery in Göttweig

- No. 15 – Symphony in F major preserved in a manuscript of c. 1770 in the Fürstlich

Thurn und Taxis Hofbibliothek in Regensburg

- No. 16 – Symphony in B-flat major preserved in a manuscript of c. 1770 in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague

- No. 17 – Symphony in G major preserved in a manuscript collection from the early 1770s in the Music Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

- No. 18 - Symphony in F major preserved in a manuscript of c. 1771 in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague

- Nos. 19-25 – Seven symphonies [C major, D major, D major, F major, C major, D major, F major] cited in a 1771 catalog of the musical holdings of Stift Vorau [the music for Nos. 23-25 is lost]

- Nos. 26-31 – Six symphonies [C major, A major, F major, D major, B-flat major, G major] preserved in the print Six Overtures (London: William Napier, [c. 1772])

- Nos. 32-35 – Four symphonies [D major, E-flat major, A major, B-flat major] cited in an Austrian catalog of unidentifiable origins compiled c. 1775

- Nos. 36-41 – Six symphonies [D major, B-flat major, G major, E-flat major, C major, F major] offered for sale in the Breitkopf catalog of 1776/77 [all of which are lost]

- Nos. 42-47 – Six symphonies [C major, D major, E-flat major, F major, G major, B-flat major] dated 1778 in manuscripts from the library of the Pfarrkirche in Weyarn

- No. 48 – Symphony in D major dated 1780 in a manuscript in the Biblioteca Civica Girolamo Tartarotti in Rovereto

- Nos. 49-53 - Five symphonies [C major, D major, F major, F major, G major] preserved in manuscripts of c. 1780 in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague

- No. 54 – Symphony in E-flat major preserved in an undated manuscript in the České Muzeum Hudby in Prague

- No. 55 – Symphony in G major preserved in an undated manuscript in the Biblioteca Estense in Modena

Overtures

- Overtures are preserved for all of the Mysliveček operas and oratorios that survive in score, most of them disseminated in manuscript and printed form to be performed as separate instrumental pieces. A complete listing of sources is presented in Freeman, Josef Mysliveček. The most significant print of overtures is the Sei sinfonie da orchestra published by Ranieri del Vivo in Florence c. 1777, the first anthology of symphonic works ever known to have been published in Italy.

Operas

See List of Operas by Mysliveček.

Miscellaneous secular dramatic works

- Il Parnaso confuso (c. 1765), dramatic cantata

- Elfrida (1774), play with choruses (lost)

- Das ausgerechnete Glück (1777), children's operetta (lost)

- Theodorich und Elisa (c. 1777), melodrama

Oratorios

- Il Tobia (Padua, 1769)

- I pellegrini al sepolcro (Padua, 1770)

- Giuseppe riconosciuto (Padua, c. 1770) - lost

- Adamo ed Eva (Florence, 1771)

- La Betulia liberata (Padua, 1771) - lost

- La passione di Nostro Signore Gesù Cristo (Florence, 1773)

- La liberazione d'Israele (1773 – c. 1774) - lost, perhaps composed in Naples, first recorded performance in Prague in 1775

- Isacco figura del redentore (Florence, 1776; revised for a performance in Munich in March 1777 known to Mozart under the title Abramo ed Isacco)

Other vocal works

Secular cantatas

- Cantata per S.E. Marino Cavalli (1768) - lost

- Narciso al fonte (1768) - lost

- Cantata a 2 (by 1771)

- Enea negl'Elisi (1777) - lost

- Armida

- Ebbi, non ti smarir

- Non, non turbati, o Nice

- 6 birthday cantatas written between 1767 and 1779 during his stays in Naples - lost

Arias

- Ah che fugir … Se il ciel mi chi rida;

- 3 duetti notturni (2 vv, insts)

Sacred works

- Veni sponsa Christi (1771)

- Lytanie laurentanae

- Offertorium Beatus Bernardy

Recordings

- Opera Il Medonte. L'Arte del Mondo. dir. Werner Ehrhardt, dhm, 2011

- Opera Il Bellerofonte. Prague Chamber Orchestra dir. Zoltán Peskó, Supraphon, 2003

Cinema

A documentary film about the genesis of the 2013 Prague production of Mysliveček's opera L'Olimpiade, produced by Mimesis Film and directed by Petr Václav, was released in 2015 under the title Zpověď zapomenutého (Confession of the Vanished). It was a winner of the Trilobit Beroun award of 2016. A full-length biopic devoted to Josef Mysliveček is scheduled to be produced by Jan Macola of Mimesis Film with a planned release date of 2017.[9]

Notes

- ↑ A comprehensive treatment of Mysliveček's life and works is found in Daniel E. Freeman, Josef Mysliveček, "Il Boemo" (Sterling Heights, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 2009).

- ↑ See Freeman, Josef Mysliveček, pp. 3 & 100.

- ↑ A collection of essays centered around the Pavia performance of Mysliveček's Demetrio of 1773 is found in Mariateresa Dellaborra, ed., "Il ciel non soffre inganni": Attorno al Demetrio di Mysliveček, "Il Boemo" (Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana, 2011).

- ↑ Mysliveček was first mentioned by Leopold Mozart in his Reisenotizen (travel notes) from 24–29 March 1770, after which he appears in 28 surviving letters written by members of the Mozart family. These are translated in Emily Anderson, ed., The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 3rd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985). Anderson's translations of the Mozart correspondence were first published in 1938. She recognized the importance of Mysliveček's association with the Mozart family from her work as a translator and took care to include his portrait among the illustrations prepared for the edition. A complete appraisal of Mysliveček's personal and musical connections with the Mozart family is provided in Freeman, Josef Mysliveček, pp. 225–55.

- ↑ New insights into Mysliveček's rapport with the Mozart family during their trips to Italy are presented in Giuseppe Rausa, "Mysliveček e Mozart: stranieri in Italia," in Il ciel non soffre inganni: Attorno al Demetrio di Mysliveček, 'Il Boemo', edited by Mariateresa Dellaborra (Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana, 2011), 45-82.

- ↑ The letter of 11 October 1777 that confirms Mysliveček's facial disfigurement is translated in Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 302-6, and is discussed in Freeman, Josef Mysliveček, 75-79.

- ↑ This incident is documented in issues of the Florentine newspaper Gazzetta universale published during the run of Armida (see Freeman, Josef Mysliveček, pp. 89–90).

- ↑ A. Evans and R. Dearling, Josef Mysliveček (1737–1781): a Thematic Catalogue of his Instrumental and Orchestral Works, Musikwissenschaftliche Schriften XXXV (Munich & Salzburg: Katzbichler, 1999) is the only published thematic catalog of Mysliveček's works. Freeman, Josef Mysliveček, contains new works' lists with corrections to the Evans/Dearling catalog, which contains many mistakes and omissions.

- ↑ These plans are outlined in an article in the Prague Monitor of 30 July 2013 and the Mimesis Film website.

See also

References

- Freeman, Daniel E. Josef Mysliveček, 'Il Boemo'. Sterling Heights, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 2009.

- Evans, Angela, and Robert Dearling. Josef Mysliveček (1737–1781): a Thematic Catalogue of His Instrumental and Orchestral Works. Munich and Salzburg: Katzbichler, 1999.

- Josef Mysliveček

- Mozart Contemporaries: Myslivecek, Joseph

- Karadar Classical Music Dictionary Includes full libretto of Mysliveček's Il Gran Tamerlano, 1772.

- W.A.Mozart and Josef Mysliveček Discussion begins about halfway down page.

- More at the same site Links to several other language pages.

External links

- Free scores by Josef Mysliveček at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free scores by Josef Mysliveček in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- A variety of vocal and instrumental music in manuscript, including eight complete operas, available for viewing and downloading at http://www.internetculturale.it (Subcategory: Digital Contents)