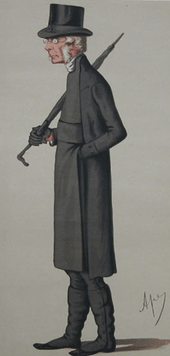

John Colenso

| The Right Reverend John William Colenso | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Natal | |

| |

| Church | Church of England |

| See | Natal |

| In office | 1853 – 20 June 1883 |

| Predecessor | none |

| Successor | Hamilton Baynes |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

24 January 1814 St Austell, Cornwall, England |

| Died |

20 June 1883 (aged 69) Durban, Natal Colony |

| Previous post | Rector of Forncett St Mary |

John William Colenso (24 January 1814 – 20 June 1883) was a British mathematician, theologian, Biblical scholar and social activist, who was the first Church of England Bishop of Natal.

Early life and education

Colenso was born at St Austell, Cornwall, on 24 January 1814. His father (John William Colenso) invested his capital into a mineral works in Pentewan, Cornwall, but the speculation proved to be ruinous when the investment was lost following a sea flood. His cousin was William Colenso, a missionary in New Zealand.

Family financial problems meant that Colenso had to take a job as an usher in a private school before he could attend University. These earnings and a loan of £30 raised by his relatives paid for his first year at St John's College, Cambridge where he was a sizar scholar. In 1836 he was Second Wrangler and Smith's Prizeman at Cambridge, and in 1837 he became fellow of St John's.[1] Two years later he went to Harrow School as mathematical tutor, but the step proved an unfortunate one. The school was at its lowest ebb, and Colenso not only had few pupils, but lost most of his property in a fire. He returned to Cambridge burdened by an enormous debt of £5,000. However, within a relatively short period of time he paid off this debt by diligent tutoring and the sale to Longmans of his copyright interest in the highly successful and widely read manuals he had written on algebra (in 1841) and arithmetic (in 1843).

Career

Colenso's early theological thinking was heavily influenced by Frederick Maurice to whom he was introduced by his wife and by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

In 1846 he became rector of Forncett St Mary, Norfolk, and in 1853 he was recruited by the Bishop of Cape Town, Robert Gray, to be the first Bishop of Natal.[2]

Life in Africa

Colenso was a significant figure in the history of the published word in nineteenth century South Africa. He first wrote a short but vivid account of his initial journeying in Natal, Ten Weeks in Natal. A Journal of a first tour of Visitation among the colonists and Zulu Kaffirs of Natal (Cambridge, 1855). Using the printing press he brought to his missionary station at Ekukhanyeni in Natal, and with William Ngidi he published the first Zulu Grammar and English/Zulu dictionary.[3][4] His 1859 journey across Zululand to visit Mpande (the then Zulu King) and meet with Cetshwayo (Mpande's son and the Zulu King at the time of the Zulu War) was recorded in his book First Steps of the Zulu Mission.[5] The same journey was also described in the first book written by native South Africans in Zulu – Three Native Accounts (with accounts written by Magema Fuze, Ndiyane and William Ngidi).[6] He also translated the New Testament and other portions of Scripture into Zulu.

Religious debate

Through the influence of his talented and well-educated wife, Colenso became one of only a handful of theologians to embrace Frederick Maurice, who was raised a Unitarian but joined the Church of England to help it "purify and elevate the mind of the nation".[7]

Before his missionary career Colenso's volume of sermons dedicated to Frederick Maurice signalled the critical approach he would later apply to biblical interpretation and the baleful impact on native Africans of colonial expansion in southern Africa.

Colenso first courted controversy with the publication in 1855 of his Remarks on the Proper Treatment of Polygamy;[8] one of the most cogent Christian-based arguments for tolerance of polygamy.[9]

Colenso's experiences in Natal informed his development as a religious thinker. In his commentary upon St Paul's Epistle to the Romans (1861) [10] he countered the doctrine of eternal punishment and the contention that Holy Communion was a precondition to salvation. Colenso, as a missionary, would not preach that the ancestors of newly Christianised Africans were condemned to eternal damnation. The thought provoking questions put to him by students at his missionary station encouraged him to re-examine the contents of the Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua and question whether certain sections of these books should be understood as literally or historically accurate. His conclusions, positive and negative, were published in a series of treatises on the Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua, over a period of time from 1862 to 1879.[11][12] The publication of these volumes created a scandal in England and were the cause of a number of anguished and patronising counter-blasts from those (clergy and laity alike) who refused to countenance the possibility of biblical fallibility. Colenso's work attracted the notice of biblical scholars on the continent such as Abraham Kuenen and played an important contribution in the development of biblical scholarship[13]

Colenso's biblical criticism and his high-minded views about the treatment of African natives created a frenzy of alarm and opposition from the High Church party in South Africa and in England. As controversy raged in England, the South African bishops headed by Bishop Gray pronounced Colenso's deposition in December 1863.[14] Colenso, who had refused to appear before this tribunal otherwise than by sending a proxy protest (delivered by his friend Wilhelm Bleek), appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. The Privy Council eventually decided that the Bishop of Cape Town had no coercive jurisdiction and no authority to interfere with the Bishop of Natal. In view of this finding of ultra vires there was no opinion given upon the allegations of heresy made against Colenso. The first Lambeth Conference was convened in 1867 to address concerns raised by the Privy Council's decision in favour of Colenso.

His adversaries, though unable to remove him from his episcopal office, succeeded in restricting his ability to preach both in Natal and in England. Bishop Gray not only excommunicated him but consecrated a rival bishop (W.K. Macrorie), who took the title of "Bishop of Maritzburg" (the latter a common name for Pietermaritzburg). The contributions of the missionary societies were withdrawn, but an attempt to deprive him of his episcopal income and the control of St Peter's Cathedral in Pietermaritzburg was frustrated by another court ruling. Colenso, encouraged by a handsome testimonial raised in England to which many clergymen subscribed, returned to his diocese. A rival cathedral was built but it has long been sold and moved. The new Cathedral of the Nativity, beside St Peter's, honours both Bishop Colenso and Bishop Macrorie in the names it has given to its halls.

Advocacy of native African causes

Colenso devoted the latter years of his life to further labours as a biblical commentator and as an advocate for native Africans in Natal and Zululand who had been unjustly treated by the colonial regime in Natal. In 1874 he took up the cause of Langalibalele and the Hlubi and Ngwe tribes in representations to the Colonial Secretary, Lord Carnarvon.[15] Langalibalele had been falsely accused of rebellion in 1873 and, following a charade of a trial, was found guilty and imprisoned on Robben Island. In taking the side of Langalibalele against the Colonial regime in Natal and Theophilus Shepstone, the Secretary for Native Affairs, Colenso found himself even further estranged from colonial society in Natal.

Colenso's concern about the misleading information that was being provided to the Colonial Secretary in London by Shepstone and the Governor of Natal prompted him to devote much of the final part of his life to championing the cause of the Zulus against Boer oppression and official encroachments. He was a prominent critic of Sir Bartle Frere's efforts to depict the Zulu kingdom as a threat to Natal. Following the conclusion of the Anglo-Zulu War he interceded on behalf of Cetshwayo with the British government and succeeded in getting him released from Robben Island and returned to Zululand. Colenso's campaigns revealed the dark, racist foundation underpinning the colonial regime in Natal and made him more enemies among the colonists than he had ever made among the clergy.

He was known as Sobantu (father of the people) to the native Africans in Natal and had a close relationship with members of the Zulu royal family; one of whom, Mkhungo (a son of Mpande), was taught at his school in Bishopstowe. After his death his wife and daughters continued his work supporting the Zulu cause and the organisation that eventually became the African National Congress.

Polygenism

Colenso was a polygenist; he believed in CoAdamism that races had been created separately. Colenso pointed to monuments and artifacts in Egypt to debunk monogenist beliefs that all races came from the same stock. Ancient Egyptian representations of races for example showed exactly how the races looked today. Egyptological evidence indicated the existence of remarkable permanent differences in the shape of the skull, bodily form, colour and physiognomy between different races which are difficult to reconcile with biblical monogenesis. Colenso believed that racial variation between races was so great, that there was no way all the races could have come from the same stock just a few thousand years ago, he was unconvinced that the climate could change racial variation, he also with other biblical polygenists believed that monogenists had interpreted the bible wrongly.[16] Colenso said “It seems most probable that the human race, as it now exists, had really sprung from more than one pair”. Colenso denied that polygenism caused any kind of racist attitudes or practices, like many other polygenists he claimed that monogenesis was the cause of slavery and racism. Colenso claimed that each race had sprung from a different pair of parents, and that all races had been created equal by God.[16]

Later life and death

Colenso died at Durban on 20 June 1883. His daughter Frances Ellen Colenso (1849–1887) published two books on the relations of the Zulus to the British (History of the Zulu War and Its Origin[17] in 1880 and The Ruin of Zululand[18] in 1885) that explained recent events in Zululand from a pro-Zulu perspective. His oldest daughter, Harriette E Colenso (b. 1847), took up Colenso's mantle as advocate for the Zulus in opposition to their treatment by the authorities appointed by Natal, especially in the case of Dinizulu in 1888–1889 and in 1908–1909.

Personal life

Colenso married Sarah Frances Bunyon in 1846,[7] and they had five children, Harriet Emily, Frances Ellen, Robert John, Francis "Frank" Ernest, and Agnes.

In popular culture

- In the 1979 film Zulu Dawn, Colenso is sympathetically portrayed by Freddie Jones, as a principled critic of the decision to declare war on Cetshwayo and the Zulus.

References

- ↑ "Colenso, John William (CLNS832JW)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Josephine Guy (4 January 2002). The Victorian Age: An Anthology of Sources and Documents. Taylor & Francis. pp. 299–. ISBN 978-0-203-00904-8. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso (bp. of Natal.) (1861). Zulu-English dictionary. Davis. pp. 5–. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso (1890). First Steps in Zulu: Being an Elementary Grammar of the Zulu Language. P. Davis & Sons. pp. 1–. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso (1860). First Steps of the Zulu Mission (October 1859). Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso (1901). Three Native Accounts of the Visit of the Bishop of Natal in September and October, 1859, to Umpande, King of the Zulus. Vause, Slatter. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 Donald R. Morris (1998). The Washing of the Spears: A History of the Rise of the Zulu Nation Under Shaka and Its Fall in the Zulu War of 1879. Da Capo Press. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-0-306-80866-1. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso (1855). Remarks on the Proper Treatment of Cases of Polygamy Converts from Heathensm. May & Davis. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Steven Kaplan (1995). Indigenous Responses to Western Christianity. NYU Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-8147-4649-3. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso; Jonathan A. Draper, (ed.) (2003). Commentary on Romans. Cluster Publications. ISBN 978-1-875053-30-8. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso (1862). The Pentateuch and Book of Joshua Critically Examined. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ John William Colenso (bp. of Natal.) (1865). The Pentateuch and Book of Joshua critically examined. (People's ed.). Empty Field. pp. 19–. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Timothy Larsen (2004). Contested Christianity: The Political and Social Contexts of Victorian Theology. Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-0-918954-93-0. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Draper 2003, pp. 306-325.

- ↑ Bartle Frere; John William Colenso (2000). The Zulu War: Correspondence Between His Excellency the High Commissioner and the Bishop of Natal Referring to the Present Invasion of Zululand, with Extracts from the Blue Books and Additional Information from Other Sources. Archival Publ. Internat. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 Colin Kidd (7 September 2006). The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600-2000. Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-1-139-45753-8. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Frances Colenso (22 September 2011). History of the Zulu War and Its Origin. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-03209-4. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Frances Ellen Colenso (6 March 2012). The Ruin of Zululand: An Account of British Doings in Zululand Since the Invasion of 1879, Volume 1... Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-277-20515-2. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

Bibliography

- Ausloos, Hans "John William Colenso (1814–1883) and the Deuteronomist." Revue Biblique 113 (2006): 372 397.

- Draper, Jonathan A. (2003). "The Trial of Bishop John William Colenso". In Jonathan A. Draper. The Eye of the Storm: Bishop John William Colenso and the Crisis of Biblical Inspiration. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-40158-8.

- Ch Hodge (1861). Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Arithmetic. Designed for Use in Schools (1867 revised edition) National Library of Australia

- John William Colenso (1855). Ten weeks in Natal: A journal of a first tour of visitation among the colonists and Zulu Kafirs of Natal. Macmillan & co. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- John William Colenso (bp. of Natal.) (1866). Natal sermons. Retrieved 19 September 2013. (The 1st and 2nd series of the Natal Sermons have been re-printed, but the 3rd and 4th series, published only in South Africa and extremely rare, have not yet been reprinted.)

- Frances Bunyon Colenso (1958). Colenso Letters from Natal. Shuter and Shooter. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- John William Colenso (1873). Lectures on the Pentateuch and the Moabite Stone. Longmans, Green. pp. 2–. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Cox, George William (1888). The life of John William Colenso, D.D.: bishop of Natal. W. Ridgway. Retrieved 18 September 2013. (Though somewhat hagiographical, Cox's work is of major importance, containing as it does many of Bishop Colenso's letters.)

- F. Frank Leslie Cross; Elizabeth Anne Livingstone (2005). The Oxford Dictionary Of The Christian Church. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. pp. 308–309. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Jeff Guy (January 1994). The Destruction of the Zulu Kingdom: The Civil War in Zululand, 1879-1884. University of Natal Press. ISBN 978-0-86980-892-4. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Jeff Guy (1983). The Heretic: A Study of the Life of John William Colenso, 1814-1883. Ravan Press. ISBN 978-0-86975-168-8. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Jeff Guy (2001). The View Across the River: Harriette Colenso and the Zulu Struggle Against Imperialism. New Africa Books. ISBN 978-0-86486-373-7. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Hinchliff, Peter (1964). John William Colenso: Bishop of Natal. Nelson. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Alfred Leslie Rowse (1 July 1989). The controversial Colensos. Dyllansow Truran. ISBN 978-1-85022-047-3. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Sugirtharajah, R. S. (2001). The Bible and the Third World: Precolonial, Colonial and Postcolonial Encounters. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00524-1. *Sugirtharajah, R. S. (2005). The Bible and Empire: Postcolonial Explorations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82493-4.

Books written in response to Colenso's views on the Pentateuch

- Micaiah HILL (1863). Christ or Colenso? or, a full reply to the objections of the ... Bishop of Natal to the Pentateuch [in his work entitled: "the Pentateuch and Book of Joshua critically examined"]. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- John Cumming; John William Colenso (bp. of Natal.) (1863). Moses right and bishop Colenso wrong, lectures in reply to 'Bishop Colenso on the Pentateuch'. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Garland George Vallis (August 2009). Plain Possible Solutions of the Objections of John William Colenso. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-113-41572-1. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- James Robert Page; John William Colenso (bp. of Natal.) (1863). The pretensions of bishop Colenso [in The Pentateuch and book of Joshua critically examined] to impeach the wisdom and veracity of the compilers of the holy Scriptures considered. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Jacob Mair Hirschfelder; John William Colenso (bp. of Natal.) (1863). The Scriptures defended, a reply to bishop Colenso's book, on the Pentateuch, and the book of Joshua. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- William H. Hoare (September 2009). The Age and Authorship of the Pentateuch Considered: In Further Reply to Bishop Colenso. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-113-94965-3. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- William Henry Green (1863). The Pentateuch Vindicated from the Aspersions of Bishop Colenso. J. Wiley. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Alexander Moody Stuart (January 2010). Our Old Bible; Moses on the Plains of Moab. General Books LLC. ISBN 978-1-152-68210-8. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Joseph Benjamin M'Caul (January 2010). Bishop Colenso's Criticism Criticised; In a Series of Ten Letters Addressed to the Editor of the "Record" Newspaper; With Notes and a PostScript. General Books LLC. ISBN 978-1-152-74897-2. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Ezekiel Stone Wiggins; John William Colenso (1864). The Architecture of the Heavens: Containing a New Theory of the Universe and the Extent of the Deluge, and the Testimony of the Bible and Geology in Opposition to the Views of Dr. Colenso. J. Lovell. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John William Colenso. |

- Material relating to Colenso at Lambeth Palace Library

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "John Colenso", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- "Archival material relating to John Colenso". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of John William Colenso at the National Portrait Gallery, London

| Anglican Church of Southern Africa titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| New diocese | Bishop of Natal 1853–1883 |

Succeeded by Hamilton Baynes |