John Betjeman

| Sir John Betjeman | |

|---|---|

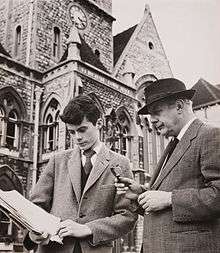

.jpg) Betjeman in 1961 | |

| Born |

John Betjemann 28 August 1906 Parliament Hill Mansions, Lissenden Gardens, Gospel Oak, London, England, UK |

| Died |

19 May 1984 (aged 77) Trebetherick, Cornwall, England, UK |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, broadcaster |

| Spouse |

Hon. Penelope Chetwode (m. 1933–1984) |

| Partner |

Lady Elizabeth Cavendish (1951–1984) |

| Children |

Paul Betjeman Candida Lycett Green |

Sir John Betjeman, CBE (/ˈbɛtʃəmən/; 28 August 1906 – 19 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster who described himself in Who's Who as a "poet and hack". He was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1972 until his death.

He was a founding member of the Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture. He began his career as a journalist and ended it as one of the most popular British Poets Laureate and a much-loved figure on British television.

Life

Early life and education

Betjeman was born "John Betjemann". His parents, Mabel (née Dawson) and Ernest Betjemann, had a family firm at 34–42 Pentonville Road which manufactured the kind of ornamental household furniture and gadgets distinctive to Victorians.[1]

He changed his name to the less German-looking "Betjeman" during the First World War. His father's forebears had actually come from the present day Netherlands and had, ironically, added the extra -n during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War to avoid the anti-Dutch sentiment existing at the time[2] more than a century earlier, setting up their home and business in Islington, London.

Betjeman was baptised at St Anne's Church Highgate Rise, a 19th-century church at the foot of Highgate West Hill. The family lived at Parliament Hill Mansions in the Lissenden Gardens private estate in Highgate in north London.

In 1909, the Betjemanns moved half a mile north to more opulent Highgate. From West Hill they lived in the reflected glory of the Burdett-Coutts estate:

- "Here from my eyrie, as the sun went down,

- I heard the old North London puff and shunt,

- Glad that I did not live in Gospel Oak."[3]

Betjeman's early schooling was at the local Byron House and Highgate School, where he was taught by poet T. S. Eliot. After this, he boarded at the Dragon School preparatory school in North Oxford and Marlborough College, a public school in Wiltshire. In his penultimate year, he joined the secret 'Society of Amici'[4] in which he was a contemporary of both Louis MacNeice and Graham Shepard. He founded The Heretick, a satirical magazine that lampooned Marlborough's obsession with sport. While at school, his exposure to the works of Arthur Machen won him over to High Church Anglicanism, a conversion of importance to his later writing and conception of the arts.[5]

Magdalen College, Oxford

Betjeman entered the University of Oxford with difficulty, having failed the mathematics portion of the university's matriculation exam, Responsions. He was, however, admitted as a commoner (i.e. a non-scholarship student) at Magdalen College and entered the newly created School of English Language and Literature. At Oxford, Betjeman made little use of the academic opportunities. His tutor, a young C. S. Lewis, regarded him as an "idle prig" and Betjeman in turn considered Lewis unfriendly, demanding, and uninspired as a teacher.[6] Betjeman particularly disliked the coursework's emphasis on linguistics, and dedicated most of his time to cultivating his social life, his interest in English ecclesiastical architecture, and to private literary pursuits.

At Oxford he was a friend of Maurice Bowra, later (1938 to 1970) to be Warden of Wadham. Betjeman had a poem published in Isis, the university magazine, and served as editor of the Cherwell student newspaper during 1927. His first book of poems was privately printed with the help of fellow student Edward James. He famously brought his teddy bear Archibald Ormsby-Gore up to Magdalen with him, the memory of which inspired his Oxford contemporary Evelyn Waugh to include Sebastian Flyte's teddy Aloysius in Brideshead Revisited. Much of this period of his life is recorded in his blank verse autobiography Summoned by Bells published in 1960 and made into a television film in 1976.[7]

It is a common misapprehension, cultivated by Betjeman himself, that he did not complete his degree because he failed to pass the compulsory holy scripture examination, known colloquially as "Divvers", short for "Divinity". In Hilary term 1928, Betjeman failed Divinity for the second time. He had to leave the university for the Trinity term to prepare for a retake of the exam; he was then allowed to return in October. Betjeman then wrote to the Secretary of the Tutorial Board at Magdalen, G. C. Lee, asking to be entered for the Pass School, a set of examinations taken on rare occasions by undergraduates who are deemed unlikely to achieve an honours degree. In Summoned by Bells Betjeman claims that his tutor, C. S. Lewis, said "You'd have only got a third" – but he had informed the tutorial board that he thought Betjeman would not achieve an honours degree of any class.[6]

Permission to sit the Pass School was granted. Betjeman famously decided to offer a paper in Welsh. Osbert Lancaster tells the story that a tutor came by train twice a week (first class) from Aberystwyth to teach Betjeman. However, Jesus College had a number of Welsh tutors who more probably would have taught him. Betjeman finally had to leave at the end of the Michaelmas term, 1928.[8] Betjeman did pass his Divinity examination on his third try but was 'sent down' after failing the Pass School. He had achieved a satisfactory result in only one of the three required papers (on Shakespeare and other English authors).[6] Betjeman's academic failure at Oxford rankled with him for the rest of his life and he was never reconciled with C.S. Lewis, towards whom he nursed a bitter detestation. This situation was perhaps complicated by his enduring love of Oxford, from which he accepted an honorary doctorate of letters in 1974.[6]

After university

Betjeman left Oxford without a degree. Whilst there, however, he had made the acquaintance of people who would later influence his work, including Louis MacNeice and W. H. Auden.[9] He worked briefly as a private secretary, school teacher and film critic for the Evening Standard, where he also wrote for their high-society gossip column, the Londoner's Diary. He was employed by the Architectural Review between 1930 and 1935, as a full-time assistant editor, following their publishing of some of his freelance work. Timothy Mowl (2000) says, "His years at the Architectural Review were to be his true university".[10] At this time, while his prose style matured, he joined the MARS Group, an organisation of young modernist architects and architectural critics in Britain.

Betjeman's sexuality can best be described as bisexual, but his longest and best documented relationships were with women, and a fairer analysis of his sexuality may be that he was "the hatcher of a lifetime of schoolboy crushes - both gay and straight", most of which progressed no further.[11] Nevertheless, he has been considered 'temperamentally gay', and even became a penpal of Lord Alfred 'Bosie' Douglas of Oscar Wilde fame.[12] On 29 July 1933 he married the Hon. Penelope Chetwode, the daughter of Field Marshal Lord Chetwode. The couple lived in Berkshire and had a son, Paul, in 1937, and a daughter, Candida, in 1942.

In 1937, Betjeman was a churchwarden at Uffington, the Berkshire town (since relocated to Oxfordshire) where he lived. That year, he paid for the cleaning of the church's royal arms and later presided over the conversion of the church's oil lamps to electricity.[13]

The Shell Guides were developed by Betjeman and Jack Beddington, a friend who was publicity manager with Shell-Mex Ltd, to guide Britain's growing number of motorists around the counties of Britain and their historical sites. They were published by the Architectural Press and financed by Shell. By the start of World War II 13 had been published, of which Cornwall (1934) and Devon (1936) were written by Betjeman. A third, Shropshire, was written with and designed by his good friend John Piper in 1951.

In 1939, Betjeman was rejected for active service in World War II but found war work with the films division of the Ministry of Information. In 1941 he became British press attaché in neutral Dublin, Ireland, working with Sir John Maffey. He may have been involved with the gathering of intelligence. He is reported to have been selected for assassination by the IRA. The order was rescinded after a meeting with an unnamed Old IRA man who was impressed by his works.

Betjeman wrote a number of poems based on his experiences in "Emergency" World War II Ireland including "The Irish Unionist's Farewell to Greta Hellstrom in 1922" (written during the war) which contained the refrain "Dungarvan in the rain". The object of his affections, "Greta", has remained a mystery until recently revealed to have been a member of a well-known Anglo-Irish family of Western county Waterford. His official brief included establishing friendly contacts with leading figures in the Dublin literary scene: he befriended Patrick Kavanagh, then at the very start of his career. Kavanagh celebrated the birth of Betjeman's daughter with a poem "Candida"; another well-known poem contains the line Let John Betjeman call for me in a car.

After World War II

Betjeman's wife Penelope became a Roman Catholic in 1948. The couple drifted apart and in 1951 he met Lady Elizabeth Cavendish, with whom he developed an immediate and lifelong friendship.

By 1948 Betjeman had published more than a dozen books. Five of these were verse collections, including one in the USA. Sales of his Collected Poems in 1958 reached 100,000.[14] The popularity of the book prompted Ken Russell to make a film about him, John Betjeman: A Poet in London (1959). Filmed in 35mm and running 11 minutes and 35 seconds, it was first shown on BBC's Monitor programme.[15]

He continued writing guidebooks and works on architecture during the 1960s and 1970s and started broadcasting. He was a founder member of the Victorian Society (1958). Betjeman was closely associated with the culture and spirit of Metro-land, as outer reaches of the Metropolitan Railway were known before the war.

In 1973 he made a widely acclaimed television documentary for the BBC called Metro-Land, directed by Edward Mirzoeff. On the centenary of Betjeman's birth in 2006, his daughter led two celebratory railway trips: from London to Bristol, and through Metro-land, to Quainton Road. In 1974, Betjeman and Mirzoeff followed up Metro-Land with A Passion for Churches, a celebration of Betjeman's beloved Church of England, filmed entirely in the Diocese of Norwich. In 1975, he proposed that the Fine Rooms of Somerset House should house the Turner Bequest, so helping to scupper the plan of the Minister for the Arts for a Theatre Museum to be housed there. In 1977 the BBC broadcast "The Queen's Realm: A Prospect of England", an aerial anthology of English landscape, music and poetry, selected by Betjeman and produced by Edward Mirzoeff, in celebration of the Queen's Silver Jubilee.

Betjeman was fond of the ghost stories of M.R. James and supplied an introduction to Peter Haining's book M.R. James – Book of the Supernatural. He was susceptible to the supernatural. Diana Mitford tells the story of Betjeman staying at her country home, Biddesden House, in the 1920s. She says, "he had a terrifying dream, that he was handed a card with wide black edges, and on it his name was engraved, and a date. He knew this was the date of his death".[16]

For the last decade of his life Betjeman suffered increasingly from Parkinson's disease. He died at his home in Trebetherick, Cornwall on 19 May 1984, aged 77, and is buried nearby at St Enodoc's Church.[17]

Poetry

Betjeman's poems are often humorous, and in broadcasting he exploited his bumbling and fogeyish image. His wryly comic verse is accessible and has attracted a great following for its satirical and observant grace. Auden said in his introduction to Slick But Not Streamlined, "so at home with the provincial gaslit towns, the seaside lodgings, the bicycle, the harmonium." His poetry is similarly redolent of time and place, continually seeking out intimations of the eternal in the manifestly ordinary. There are constant evocations of the physical chaff and clutter that accumulates in everyday life, the miscellanea of an England now gone but not beyond the reach of living memory.

He talks of Ovaltine and Sturmey-Archer bicycle gears. "Oh! Fuller's angel cake, Robertson's marmalade," he writes, "Liberty lampshades, come shine on us all."[18]

In a 1962 radio interview he told teenage questioners that he could not write about 'abstract things', preferring places, and faces.[19] Philip Larkin wrote of his work, "how much more interesting & worth writing about Betjeman's subjects are than most other modern poets, I mean, whether so-and-so achieves some metaphysical inner unity is not really so interesting to us as the overbuilding of rural Middlesex".[20]

Betjeman was a practising Anglican and his religious beliefs come through in some of his poems. He combined piety with a nagging uncertainty about the truth of Christianity. Unlike Thomas Hardy, who disbelieved in the truth of the Christmas story while hoping it might be so, Betjeman affirms his belief even while fearing it might be false.[5] In the poem "Christmas", one of his most openly religious pieces, the last three stanzas that proclaim the wonder of Christ's birth do so in the form of a question "And is it true...?" His views on Christianity were expressed in his poem "The Conversion of St. Paul", a response to a radio broadcast by humanist Margaret Knight:

But most of us turn slow to see

The figure hanging on a tree

And stumble on and blindly grope

Upheld by intermittent hope,

God grant before we die we all

May see the light as did St. Paul.

Betjeman became Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom in 1972, the first Knight Bachelor to be appointed (the only other, Sir William Davenant, had been knighted after his appointment). This role, combined with his popularity as a television performer, ensured that his poetry reached an audience enormous by the standards of the time. Similarly to Tennyson, he appealed to a wide public and managed to voice the thoughts and aspirations of many ordinary people while retaining the respect of many of his fellow poets. This is partly because of the apparently simple traditional metrical structures and rhymes he uses.[21] In the early 1970s, he began a recording career of four albums on Charisma Records which included Betjeman's Banana Blush (1974) and Late Flowering Love (1974), where his poetry reading is set to music with overdubbing by leading musicians of the time.[22] His recording catalogue extends to nine albums, four singles and two compilations.

Betjeman and architecture

Betjeman had a fondness for Victorian architecture and was a founding member of the Victorian Society. He wrote on this subject in First and Last Loves (1952) and more extensively in London's Historic Railway Stations in 1972, defending the beauty of twelve stations. He led the campaign to save Holy Trinity, Sloane Street in London when it was threatened with demolition in the early 1970s.[23]

He fought a spirited but unsuccessful campaign to save the Propylaeum, known commonly as the Euston Arch, London. He is considered instrumental in helping to save St Pancras railway station, London, and was commemorated when it became an international terminus for Eurostar in November 2007. He called the plan to demolish St Pancras a "criminal folly".[24] About it he wrote, "What [the Londoner] sees in his mind's eye is that cluster of towers and pinnacles seen from Pentonville Hill and outlined against a foggy sunset, and the great arc of Barlow's train shed gaping to devour incoming engines, and the sudden burst of exuberant Gothic of the hotel seen from gloomy Judd Street."[25]

On the reopening of St Pancras station in 2007, a statue of Betjeman was commissioned from curators Futurecity. A proposal by artist Martin Jennings was selected from a shortlist. The finished work was erected in the station at platform level, including a series of slate roundels depicting selections of Betjeman's writings.[24]

Betjeman was given the remaining two-year lease on Victorian Gothic architect William Burges's Tower House in Holland Park upon leaseholder Mrs E.R.B. Graham's death in 1962.[26] Betjeman felt he could not afford the financial implications of taking over the house permanently, with his potential liability for £10,000 of renovations upon the expiration of the lease.[26] After damage from vandals, restoration began in 1966. Betjeman's lease included furniture from the house by Burges, and Betjeman gave three pieces, the Zodiac settle, the Narcissus washstand, and the Philosophy cabinet, to Evelyn Waugh.[27]

Betjeman responded to architecture as the visible manifestation of society's spiritual life as well as its political and economic structure. He attacked speculators and bureaucrats for what he saw as their rapacity and lack of imagination. In the preface of his collection of architectural essays First and Last Loves he says, "We accept the collapse of the fabrics of our old churches, the thieving of lead and objects from them, the commandeering and butchery of our scenery by the services, the despoiling of landscaped parks and the abandonment to a fate worse than the workhouse of our country houses, because we are convinced we must save money."

In a BBC film made in 1968 but not broadcast at that time, Betjeman described the sound of Leeds to be of "Victorian buildings crashing to the ground". He went on to lambast John Poulson's British Railways House (now City House), saying how it blocked all the light out to City Square and was only a testament to money with no architectural merit. He also praised the architecture of Leeds Town Hall.[28][29] In 1969 Betjeman contributed the foreword to Derek Linstrum's Historic Architecture of Leeds.[30]

Betjeman was for over 20 years a trustee of the Bath Preservation Trust and was Vice-President from 1965 to 1971, at a time when Bath — a city rich in Georgian architecture — came under increasing pressure from modern developers and a proposed major road to cut across the city.[31] He also created a short television documentary called "Architecture of Bath", in which he voiced his concerns about the way the city's architectural heritage was being mis-treated.

Legacy

- A memorial window, designed by John Piper, in All Saints' Church, Farnborough, Berkshire, where Betjeman lived in the nearby Rectory.

- The Betjeman Millennium Park at Wantage in Oxfordshire, where he lived from 1951 to 1972 and where he set his book Archie and the Strict Baptists

- One of the roads in Pinner, a town covered in Betjeman's film Metro-Land is called Betjeman Close, while another in Chorleywood, also covered in Metro-Land, is called Betjeman Gardens.

- The John Betjeman Poetry Competition for Young People (2006–) is open to 10- to 13-year-olds living anywhere in the British Isles (including the Republic of Ireland), with a first prize of £1,000. In addition to prizes for individual finalists, state schools who enter pupils may win one of six one-day poetry workshops.[32]

- One of the engines on the pier railway at Southend-on-Sea is named Sir John Betjeman (the other Sir William Heygate).

- A British Rail Class 86 AC electric locomotive, 86229, was named Sir John Betjeman by the man in person at St Pancras station on 24 June 1983,[33] just before his death; it was renamed Lions Group International in 1998 and is now in storage.

- In 2003, to mark their centenary, the residents of Lissenden Gardens in north London put up a blue plaque to mark Betjeman's birthplace.

- In 2006, a blue plaque was installed on Betjeman's childhood home, 31 West Hill, Highgate, London N6.[34]

- The statue of Betjeman at St Pancras station in London by sculptor Martin Jennings was unveiled in 2007.

- In 2012 Betjeman featured on BBC Radio 4 as author of the week on The Write Stuff.[35]

- On 1 September 2014 Betjeman was the subject of the hour-long BBC Four documentary Return to Betjemanland, presented by his biographer A. N. Wilson.[36] At the start of the broadcast, there was a spoken tribute to Betjeman's daughter Candida Lycett Green, who had died just twelve days earlier on 19 August, aged 71.[37]

Awards and honours

- 1960 Queen's Medal for Poetry

- 1960 Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE)

- 1968 Companion of Literature, the Royal Society of Literature

- 1969 Knight Bachelor

- 1972 Poet Laureate

- 1973 Honorary Member, the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

- 2011 Honoured by the University of Oxford, his alma mater, as one of its 100 most distinguished members from ten centuries.[38]

Works

Selected works of poetry:

- Mount Zion (1932)

- Continual Dew (1937)

- Old Lights For New Chancels (1940)

- New Bats in Old Belfries (1945)

- A Few Late Chrysanthemums (1954)

- Poems in the Porch (1954)

- Summoned by Bells (1960)

- High and Low (1966)

- A Nip in the Air (1974)

Notes

- ↑ "Survey of London: volume 47: Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville". English Heritage. 2008. pp. 339–372. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ↑ Mowl, Timothy (2000). Stylistic Cold Wars, Betjeman versus Pevsner, p 13.

- ↑ Betjeman, John (1960). Summoned by Bells. John Murray. p. 5.

- ↑ Paths of Progress: A History of Marlborough College by Rt Hon Peter Brooke MP and Thomas Hinde

- 1 2 Gardner, Kevin (2005). Faith and Doubt of John Betjeman: An Anthology of Betjeman's Religious Verse. Continuum International. ASIN B00NPOJLVM.

- 1 2 3 4 Priestman, Judith, "The dilettante and the dons", Oxford Today, Trinity term, 2006.

- ↑ John Betjeman: a bibliography (2006) William S. Peterson Clarendon Press

- ↑ B. Hillier, Young Betjeman, pp. 181–194.

- ↑ Taylor-Martin, Patrick (1983). John Betjeman, his life and work. London: Allen Lane. p. 35. ISBN 0-7139-1539-0.

- ↑ Mowl, Timothy (2000). Stylistic Cold Wars, Betjeman versus Pevsner. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5909-X.

- ↑ Thompson, Johnathan. "Betjeman Poet, hero of Middle England & a very bad boy". The Independent. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Gowers, Justin. "Why John Betjeman is a true gay icon". Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Delaney, Frank (1983). Betjeman Country. Paladin (Granada). p. 158. ISBN 0-586-08499-1.

- ↑ Website by Omni digital. "Faber". Faber. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ "BFI Screenonline: John Betjeman: A Poet in London (1959)". screenonline.org.uk. 28 March 1960.

- ↑ Mosley, Diana (1977) A life of contrasts: the autobiography of Diana Mosley. H. Hamilton p83 ISBN 1-903933-20-X

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, OUP, 2004

- ↑ From "Myfanwy" in Old Lights for New Chancels (1940).

- ↑ John Betjeman: Recollections from the BBC Archives, BBC Worldwide (2000)

- ↑ Larkin, Philip (2010). Letters to Monica. Faber & Faber. p. 147. ISBN 978-0571239092.

- ↑ "Poetry Archive.org". Poetry Archive.org. 1 December 1967. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Mojo No 187 pp122

- ↑ Pearce, David (1989). Conservation Today. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00778-X.

- 1 2 Shukor, Steven (6 November 2007). "St Pancras faced demolition ball". BBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Betjeman, John (1972). London's Historic Railway Stations. London: John Murray. p. 11. ISBN 0-7195-2573-X.

- 1 2 Wilson, A. N. (27 June 2011). Betjeman. Random House. pp. 208–. ISBN 978-1-4464-9305-2. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ "Zodiac Settle by William Burges". Art Fund. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Leeds International Film Festival". Leeds International Film Festival.

- ↑ Wainwright, Martin (16 February 2009). "BBC revives unaired Betjeman film forgotten for 40 years". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ↑ Linstrum, Derek; foreword by John Betjeman (1969). Historic Architecture of Leeds. Oriel Press. ISBN 0-85362-056-3.

- ↑ Peterson, William S. (2006). John Betjeman: A Bibliography. OUP. p. 440. ISBN 978-0198184034.

- ↑ "The John Betjeman Young People's Poetry Competition". Johnbetjeman.com. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ "Sir John names 'his' loco". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. August 1983. pp. 6–7. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (16 September 2006). "Betjeman's childhood home gets blue plaque". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Walton, James (17 June 2012). "Sir John Betjeman". The Write Stuff. BBC Radio. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Wilson, A. N. (28 December 2014). "Return to Betjemanland". BBC. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Dowlen, Jerry. "John Betjeman & Candida Lycett Green". Books Monthly. Jerry Dowlen on... Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ "University of Oxford Undergraduate Prospectus 2011". University of Oxford Undergraduate Prospectus 2011. University of Oxford. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

References

- Brooke, Jocelyn (1962). Ronald Firbank and John Betjeman. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Games, Stephen (2006). Trains and Buttered Toast, Introduction. London: John Murray.

- Games, Stephen (2007). Tennis Whites and Teacakes, Introduction. London: John Murray.

- Games, Stephen (2007). Sweet Songs of Zion, Introduction. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Games, Stephen (2009). Betjeman's England, Introduction. London: John Murray.

- Gardner, Kevin J. (2005). "John Betjeman." The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gardner, Kevin J. (2011) Betjeman on Faith: An anthology of his religious prose. London: SPCK.

- Gardner, Kevin J. (2010) Betjeman and the Anglican Tradition, London, SPCK.

- Green, Chris (2006). John Betjeman and the Railways. Transport for London

- Hillier, Bevis (1984). John Betjeman: a life in pictures. London: John Murray.

- Hillier, Bevis (1988). Young Betjeman. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-4531-5.

- Hillier, Bevis (2002). John Betjeman: new fame, new love. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5002-5.

- Hillier, Bevis (2004). Betjeman: the bonus of laughter. London : John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-6495-6.

- Hillier, Bevis (2006). Betjeman: the biography. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-6443-3

- Lycett Green, Candida (Ed.) (Methuen, 1994). Letters: John Betjeman, Vol.1, 1926 to 1951. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77595-X

- Lycett Green, Candida (Ed.) (Methuen, 1995). Letters: John Betjeman, Vol.2, 1951 to 1984. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-77596-8

- Lycett Green, Candida, Betjeman's stations in The Oldie, September 2006

- Matthew, H.C.G. and Harrison, B. (eds), (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (vol. 5). Oxford: OUP.

- Mirzoeff, Edward (2006). Viewing notes for Metro-land (DVD) (24pp)

- Mowl, Timothy (2000). Stylistic Cold Wars, Betjeman versus Pevsner. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5909-X

- Schroeder, Reinhard (1972). Die Lyrik John Betjemans. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag. (Thesis).

- Sieveking, Lancelot de Giberne (1963). John Betjeman and Dorset. Dorchester: Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society.

- Stanford, Derek (1961). John Betjeman, a study. London: Neville Spearman.

- Taylor-Martin, Patrick (1983). John Betjeman, his life and work. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-1539-0

- Wilson, A. N. (2006). Betjeman. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-179702-0

Further reading

- Betjeman, John (1960). Summoned by Bells. London: John Murray.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Betjeman |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Betjeman. |

- Betjeman documentaries on BBC iPlayer

- John Betjeman Poetry Competition for Young People website

- John Betjeman fonds at University of Victoria, Special Collections

- John Betjeman Concordance at University of Victoria, Special Collections

- The Betjeman Society

- Poetry Foundation profile

- profile and poems written and audio at the Poetry Archive

- BBC4 audio interviews from People Today 24 December 1959 Home Service

- David Heathcote's A Shell Eye on England

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Cecil Day-Lewis |

Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom 1972–1984 |

Succeeded by Ted Hughes |