Jefferson Davis Highway

| Jefferson Davis Highway | |

|---|---|

| Route information | |

| Existed: | 1913 – present |

| Major junctions | |

| West end: | San Diego, California |

| East end: | Washington, D.C. |

| Location | |

| States: | California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia |

| Highway system | |

|

Auto Trails | |

The Jefferson Davis Highway was a planned transcontinental highway in the United States in the 1910s and 1920s that began in Washington, D.C., and extended south and west to San Diego, California; it was named for Jefferson Davis, who, in addition to being the first and only President of the Confederate States of America was also a U.S. Congressman and Secretary of War. Because of unintended conflict between the National Auto Trail movement and the federal government, it is unclear whether the Jefferson Davis highway ever really existed in the complete form that its founders originally intended.[1]

Background

In the first quarter of the 20th century, as the automobile gained in popularity, a system of roads began to develop informally through the actions of private interests, these were known as auto trails. They existed without the support or coordination of the federal government, although in some states, the state governments participated in their planning and development. The first of these National Auto Trails was the Lincoln Highway, which was first announced as a project in 1912.

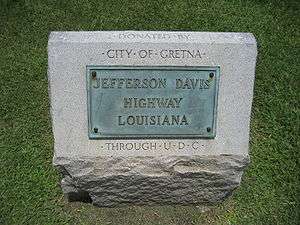

With the need for new roads being so significant, dozens of new auto trails were begun in the decade following. One such roadway was the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway, which was sponsored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The UDC planned the formation of the Jefferson Davis as a road that would start in Washington, D.C. and travel through the southern states until its terminus at San Diego. More than ten years after the construction of the Jefferson Davis was begun, it was announced that it would be extended north out of San Diego and go to the Canada–US border.

End of the auto trails

In the mid-1920s, the disparate system of national auto trails had grown cumbersome, and the federal government imposed a numbering system on the nations's highways. Using a system of even numbers for east–west routes and odd numbers for north–south routes, the numbers were imposed on the auto trails. And rather than designate one number for each auto trail, different sections of each trail were given different numerical designations. However the UDC petitioned the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads to designate the Jefferson Davis as a national highway with a single number. The Bureau's reply casts doubt on whether or not the JDMH ever really existed as a transcontinental highway:

A careful search has been made in our extensive map file in the Bureau of Public Roads and three maps showing the Jefferson Davis highways have been located, but the routes on these maps are themselves different and neither route is approximately that described by you, so that I am somewhat at a loss as to just what route your constituents are interested in. For instance, there is the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway which extends from Miami, Florida to Los Angeles (but not to San Francisco); and there is another Jefferson Davis Highway shown on the Rand-McNally maps which extends from Fairview, Kentucky the site of the Jefferson Davis monument, by a very circuitous route to New Orleans, but I find no route whatever bearing the name Jefferson Davis extending from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. [emphasis added][1]

This problem may well have been the fault of the UDC themselves. In addition to the planned transcontinental route, they also designated an auxiliary route running from Kentucky to Mississippi, as well as another that ran through Georgia. These ancillary routes were intended to commemorate important venues in Davis' life, but they also contributed to the confusion of the federal government in trying to locate exactly where the Jefferson Davis highway traveled. What is known is that when numbered highways came into existence, the Jefferson Davis National Highway was split among US 1, US 15, US 29, US 61, US 80, US 90, US 99, US 190 and others. But today many of these numbered routes themselves are no longer extant, having been supplanted by the Interstate Highway System.

Remaining portions

Although it may not be possible to view the entire length of the highway on a map today, many parts of it still exist, scattered across the country. This is an incomplete listing of some of the places today where one can see pieces of the Jefferson Davis highway.

Virginia

- The Virginia General Assembly defined the Jefferson Davis Highway in Virginia on March 17, 1922, as traveling from the District of Columbia at the 14th Street Bridge to the Commonwealth's border with North Carolina south of Clarksville, Virginia. This corridor was defined as US 1/US 15 in 1926, although US 1 took a shorter route between south of McKenney and South Hill. (The Jefferson Davis Highway used what was then SR 122 and SR 12).[2] Its original eastern terminus marker of the highway can still be found near the Virginia end of the 14th Street Bridge, which crosses the Potomac River from Washington, DC. The terminal marker was here until the 1960s, when it was moved to a nearby location for safety reasons.[1]

- SR 110 bears the name of "Jefferson Davis Highway" as it travels past the Pentagon in Arlington County between Rosslyn (near the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge) and US 1 in Crystal City.[3] This is a relatively recent extension to the original Jefferson Davis Highway. The extension was created as part of The Pentagon's road system during World War II.[3]

- State Route 712 and U.S. Route 58 are still defined as the Jefferson Davis Highway.

- The Jefferson Davis Highway now uses the following business routes:[4]

- U.S. Route 58 Business in Lawrenceville

- U.S. Route 58 Business in Boydton

- The Falling Creek and Proctor Creek highway markers in Chesterfield County, Brook Road Marker in Henrico County, Ashland Marker in Hanover County, and Elliott Grays Marker and Maury Street Marker in Richmond, Virginia are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[5]

North Carolina

The Jefferson Davis Highway traverses through the state for 162 miles (261 km). Starting at the Virginia state line along US 15 to Sanford; then on US 1 from Sanford to the South Carolina state line. Designation of highway was approved on May 28, 1955.[6][7]

South Carolina

The Jefferson Davis Highway traverses through the state for 170 miles (270 km). Starting at the North Carolina state line, it follows US 1 to the Georgia state line near Augusta. Several monuments can be found along the route including in Camden and Aiken.[8][9]

Georgia

- Highway markers can still be seen in certain spots along the old main transcontinental route through the state of Georgia.

- In Taliaferro County, in Crawfordville along US 278 (SR 12).

- In Morgan County, in Madison along Main Street (US 278/US 441/SR 12) near its intersection with Reese Street.

- In Walton County, also along US 278 (SR 12), approximately 890 yards (810 m) from the Morgan County line.[10]

- In DeKalb County, between Atlanta and Decatur, a marker stands in the traffic island at the intersection of Ponce de Leon Avenue (US 23/US 29/US 78) and East Lake Road (US 278).

- In Coweta County, in Grantville, Georgia on Main Street just north of the railroad crossing.

- An auxiliary route through Georgia went south of the main route through Irwin County and Irwinville, where Davis was ultimately captured at the end of the Civil War. This route followed SR 32 to the west of Irwinville, into neighboring Turner County, where today SR 32 retains the official name of "Jefferson Davis Highway".

- In LaGrange, a monument exists at the northeast corner of LaGrange College, which is within 1 mile (1.6 km) of Confederate Senator Benjamin Hill's National Historical Home.

Alabama

In Alabama, the segment of US 80 from Selma to Montgomery is the most famous part of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway today. On this road, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., led the 1965 Voting Rights March that helped prompt Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act. This road also extends through eastern Montgomery and today is known as the Atlanta Highway, although interstate I-85 has replaced the route to Atlanta.

Mississippi

In Biloxi, located at 2244 Beach Boulevard in front of "Beauvoir", the Last home of Jefferson Davis. It is located on the coastline overlooking the Gulf of Mexico.

Louisiana

- Jefferson Highway goes north out of New Orleans along US 61 and changes onto LA 73 near Prairieville, Louisiana. It continues along LA 73 into and across Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- In Baton Rouge, the highway follows Government Street to the levee and then north along the levee to Florida Street (US 190 Business). The road continued west across the Mississippi River on a now closed ferry into Port Allen, Louisiana.

- In Port Allen, Jefferson Highway goes north to the northern end of the town. The highway then follows west along LA 986. The roadway later changes to LA 76 and follows that highway into the town of Rosedale, Louisiana. It continued up northward through the Town of Maringouin, Livonia Fordoche on LA 77. Then crossed the Atchafalaya River via ferry LA 10 in the City of Melville, Louisiana.

Texas

The original alignment of the main route traversed from Sabine River to El Paso, via Houston, Austin, San Antonio, Alpine and Van Horn. This routing today would predominantly be along US 90, with US 290 and I-35 connecting Austin. A coastal spur, brancing from Houston to Brownsville, travels along US 59 and US 77. At least 20 markers are still in existence across the state.[11]

New Mexico

Parts along I-10 are signed as Jefferson Davis Highway. There is a marker at a rest stop that indicates the highway and that the marker was paid for by the Daughters of the Confederacy in 1955.

California

The western terminus of the highway is identified by a monument on Horton Plaza, in downtown San Diego. The formal opening of the highway at this terminus was performed by President Warren Harding. Photographs of this event are available in the archives of the San Diego Union-Tribune and in the files of the San Diego Historical Society.

Washington

In 1939, the Washington State Legislature named U.S. Route 99 as the "Jefferson Davis Highway", making it the final component of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway.[12]

Controversies and renamings

Virginia

The northeastern Virginia section of the highway approximates the route of the older Washington and Alexandria Turnpike, which received its charter from the United States Congress in 1808.[13] A street in Crystal City once designated as "Old Jefferson Davis Highway" parallels the east side of US 1, part of which is the present Jefferson Davis Highway in the area.[3] This street, which was the original route of the highway, now ends before reaching the 14th Street Bridge.[3][14] In 2011, the Arlington County Board (see Arlington County, Virginia#Government) voted to change the name of the street to "Long Bridge Drive" after the Board's chairman, who was originally from the northeastern part of the United States, stated: "I have a problem with 'Jefferson Davis' ... There are aspects of our history I'm not particularly interested in celebrating". However, the name of Jefferson Davis Highway itself, a portion of U.S. 1 that only the Virginia General Assembly could rename, remained unchanged.[15]

In its 2016 legislative package, the Arlington County Board asked the Virginia General Assembly to rename the portion of Jefferson Davis Highway that was within the County.[16] However, no member of Arlington's legislative delegation offered any such legislation during the 2016 session of the General Assembly.[17]

In February 2016, the Virginia Attorney General's office issued an advisory opinion that the City of Alexandria, unlike the neighboring Arlington County, had the legal authority to change the name of the portion of Jefferson Davis Highway that was within the City's jurisdiction.[18] In September 2016, the Alexandria City Council voted unanimously to change the name of the City's portion of the Highway.[19]

Washington

In 1998, officials of the city of Vancouver removed a marker of the Jefferson Davis Highway and placed it in a cemetery shed in an action that several years later became controversial.[20] The marker was subsequently moved twice, and eventually was placed alongside Interstate 5 on private land purchased for the purpose of giving the marker a permanent home.[21][22]

In 2002, the Washington House of Representatives unanimously approved a bill that would have removed Davis' name from the road. However, a committee of the state's Senate subsequently killed the proposal.[23][24]

In March 2016, the Washington State Legislature unanimously passed a joint memorial that asked the state transportation commission to designate the road as the "William P. Stewart Memorial Highway" to honor an African-American volunteer during the Civil War who later became a pioneer of the town and city of Snohomish.[25] In May 2016, the transportation commission agreed to the renaming.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Weingroff, Richard F. (2011-04-07). "Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration, United States Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ↑ Virginia Highways Project – VA 122

- 1 2 3 4 Arlington County Manager (September 9, 2011). "Renaming of Old Jefferson Davis Highway between Boundary Channel Drive and 12th Street South, effective April 1, 2012". Government of Arlington County, Virginia. pp. 1–3, 8. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ↑ Virginia Route Index, revised July 1, 2003 (PDF)

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "North Carolina Memorial Highways and other Named Facilities" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ Google (2011-03-03). "Jefferson Davis Highway in North Carolina" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Historical marker/historic landmark in Camden, Kershaw, SC, US; Jefferson Davis Highway (Camden, SC)". Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ↑ Google (2012-01-26). "Jefferson Davis Highway in South Carolina" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ↑ Sprinterman (2009-08-10). "Jefferson Davis Highway Marker-Walton County Georgia". U.S. Historic Survey Stones and Monuments on Waymarking.com. Groundspeak, Inc. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

- ↑ United Daughters of the Confederacy – Texas. "Jefferson Davis Highway". Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ↑ Ray, Susanna (January 24, 2002). "Jefferson Davis Highway here? Legislator outraged". HeraldNet. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ↑ Rose, C.B., Jr. (1976). Arlington County, Virginia: A History. Arlington Historical Society, Inc. p. 75.

- ↑ Coordinates of Old Jefferson Davis Highway: 38°52′01″N 77°02′52″W / 38.866862°N 77.047677°W

- ↑ (1) "Old Jefferson Davis Highway to be Renamed "Long Bridge Drive"". Newsroom. Arlington County, Virginia government. September 21, 2011. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

(2) McCaffrey, Scott (September 28, 2011). "Road Renaming Proves Another Chance to Re-Fight the Civil War". Arlington Sun Gazette. Springfield, Virginia: Sun Gazette Newspapers. Archived from the original on August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012. - ↑ (1) Sullivan, Patricia (July 10, 2015). "A road named for Confederate leader comes under fire 150 years after war". Virginia Politics. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 10, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

(2) McCaffrey, Scott. "Arlington may seek removal of 'Jefferson Davis' from highway". InsideNOVA. Leesburg, VA: Northern Virginia Media Services. Archived from the original on February 10, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

(3) Arlington County Manager (November 19, 2015). "County Board Agenda Item: Meeting of December 12, 2015: Subject: Adoption of the 2016 General Assembly Legislative Package". Government of Arlington County, Virginia. p. 2.7. Renaming Jefferson Davis Highway: Work with General Assembly and the community toward renaming the Arlington portion of Jefferson Davis Highway in a way that is respectful to all who live and work along it.

(4) McCaffrey, Scott (December 17, 2015). "Arlington County Board finalizes state legislative priorities". InsideNOVA. Leesburg, VA: Northern Virginia Media Services. Archived from the original on February 10, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016. - ↑ McCaffrey, Scott (January 28, 2016). "No push in Richmond to nix name of Jefferson Davis from highway". InsideNOVA. Leesburg, VA: Northern Virginia Media Services. Archived from the original on February 10, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ↑ McCaffrey, Scott (August 29, 2016). "'Jefferson Davis' hanging on, but for how long?: Jurisdictions have different routes to removing highway name". InsideNOVA. Leesburg, VA: Northern Virginia Media Services. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ↑ Sullivan, Patricia (September 17, 2016). "Alexandria will seek to move Confederate statue and rename Jefferson Davis Highway". Virginia politics. Washingon, D.C.: The Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Road Named for Jefferson Davis Stirs Spirited Debate". The New York Times. 2002-02-14. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

Another granite marker proclaiming the road's designation as the Jefferson Davis Highway was erected at the time in Vancouver, Wash., at the highway's southern terminus. It was quietly removed by city officials four years ago and now rests in a cemetery shed there, but publicity over the bill has brought its mothballing to light and stirred a contentious debate there about whether it should be restored.

- ↑ "History of the Jefferson Davis Park". Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Jefferson Davis Park". Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- ↑ Verhovek, Sam Howe (February 14, 2002). "Road Named for Jefferson Davis Stirs Spirited Debate". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Senate Committee Kills Plan To Rename Jefferson Davis Highway". KOMOnews.com. Seattle, Washington: Sinclair Interactive Media. August 30, 2006. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ↑ (1) "House Joint Memorial 4010: As Amended by the Senate" (PDF). 64th Legislature: 2016 Regular Session. Washington State Legislature. March 8, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

(2) "History of the Bill as of Tuesday, September 20, 2016". HJM 4010 - 2015-16: Requesting that state route number 99 be named the "William P. Stewart Memorial Highway". Washington State Legislature. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

(3) "Stewart, William P. (1839–1907)". African American History in the American West: Online Encyclopedia of Significant People and Places. BlackPast.org. 2015. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016. - ↑ (1) Cornfield, Jerry (May 17, 2016). "SR 99 to be renamed for Snohomish black Civil War soldier". HeraldNet. Everett, Washington: Everett Herald and Sound Publishing, Inc. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

(2) Muhlstein, Julie (May 21, 2016). "Highway 99 renamed in honor of Snohomish settler William P. Stewart". HeraldNet. Everett, Washington: Everett Herald and Sound Publishing, Inc. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

External links

![]() Media related to Jefferson Davis Highway at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jefferson Davis Highway at Wikimedia Commons

- US DOT, Federal Highway Administration, official website

- Map of the Southern portion of the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway; a proposed highway that was never established