Jackson Ward

|

Jackson Ward Historic District | |

|

| |

| |

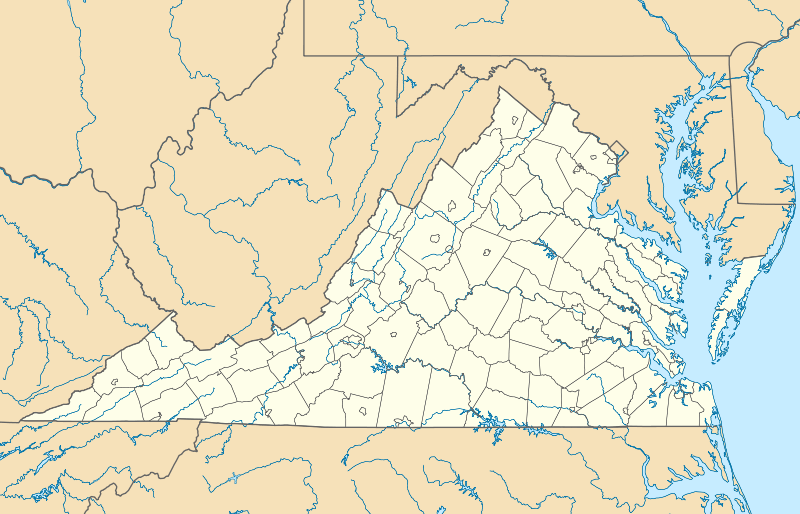

| Location | Richmond, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°32′54″N 77°26′27″W / 37.54833°N 77.44083°WCoordinates: 37°32′54″N 77°26′27″W / 37.54833°N 77.44083°W |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Greek Revival, Italianate, Late Victorian |

| NRHP Reference # | 76002187 |

| VLR # | 127-0237 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 30, 1976[1] |

| Designated NHLD | June 2, 1978[2] |

| Designated VLR | April 20, 1976; November 4, 2002; June 1, 2005; March 20, 2008[3] |

Jackson Ward is a historically African-American neighborhood in Richmond, Virginia with a long tradition of African-American businesses. It is located less than a mile from the Virginia State Capitol. It sits to the west of Court End and north of Broad Street. It was listed as a National Historic Landmark District in 1978.[4] "Jackson Ward" was originally the name of the area's political district within the city, or ward, from 1871 to 1905, yet has remained in use long after losing its original meaning.[4]

History

Center of black commerce, entertainment and religion

After the American Civil War, previously free blacks joined freed slaves and their descendants and created a thriving African-American business community, and became known as the "Black Wall Street of America." Leaders included such influential people as John Mitchell, Jr., editor of the Richmond Planet, an African American newspaper, and Maggie L. Walker. Ms. Walker was the first woman to charter and serve as president of an American bank, all the more remarkable an accomplishment as she was both African-American and was mobility-impaired. The Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site at her former Jackson Ward home is operated by the National Park Service. The house was designated a National Historic Site in 1978 and was opened as a museum in 1985.

As a center for both black commerce and entertainment, Jackson Ward was also called the "Harlem of the South". Venues along "The Deuce " (2nd Street) such as the Hippodrome Theater were frequented by the likes of Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday, Nat King Cole , James Brown and other Chitlin' circuit performers. Today, a statue of Robinson dancing on a staircase is at the center of the neighborhood at the intersection of Chamberlayne Parkway and West Leigh Street.

Other notable residents included Bishop F. M. Whittle, Addolph Dill and Max Robinson and brother Randall Robinson.

Desegregation and decline

The district was central to the Civil Rights movement in Richmond.[5] It housed the law practice of Oliver Hill, Martin A. Martin and Spottswood William Robinson III, the plaintiff attorneys in Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, one of the cases that was part of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared segregation in public schools as unconstitutional. The firm helped desegregate Richmond's schools, and also achieve pay equity for black teachers. After Martin's death, the firm continued with Hill, and later attorneys Samuel Wilbert Tucker and Henry L. Marsh[5]

Ironically, after desegregation, as black Virginians became more widely integrated into Richmond's other business and residential areas, Jackson Ward's role as a center of black commerce and entertainment declined. In addition, during the construction of the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike (today Interstate 95) in the 1950s, Jackson Ward was split in two, much to the detriment of the neighborhood. Like most older urban neighborhoods of a similar era, the housing stock of Jackson Ward deteriorated as absentee landlords took over from single-family households.

Revival

Toward the end of the 20th century, investment in the housing stock increased. The National Park Service assisted in the process by restoration of the Maggie L. Walker house and the listing of the neighborhood on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and as a National Historic Landmark District in 1978. Subsequently, the neighborhood became a Richmond Old and historic district. In the 1980s, historic tax credits by the federal government aided the restoration of dozens of houses on Leigh, Marshall and Clay Streets.

City officials hoped that construction of the Greater Richmond Convention Center and Visitors Bureau at the eastern edge of Jackson Ward would bring renewed vitality to the neighborhood.[6] However, the construction of the convention center destroyed a number of historic houses (including that used by the Hill, Tucker and Marsh law firm), and separated it from much of downtown. Vacant and substandard houses in the neighborhood have been targeted in Richmond's Neighborhoods in Bloom program. In some areas, the progress of renovation has been slow, most notably with the First Virginia Volunteers Battalion Armory, best known as the Leigh Street Armory. In the mid-1980s, the Richmond School Board leased the armory building to the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia, and the museum is expected to open in the armory in 2015.[7]

Some Richmond residents have bought houses in Jackson Ward to renovate and restore in order to live in an historic area and revive the cultural character of the neighborhood. Each first Friday of the month, First Fridays Artwalk is held at night on Broad Street. Art Galleries open their doors to an outdoor party that includes live music, including Jazz and Salsa. Local restaurants, bars and a coffee shops serve customers who come to the First Fridays Art Walk.

Architecture and landmarks

.jpg)

The earliest houses of Jackson Ward were a series of small cottages built in the Federal style. By the later 1830s up until the Civil War, the Greek Revival style was prominent, which represents a major part of Richmond's pre-war architectural heritage. And then beginning in the 1850s the Italianate styles. A major part of the district's visual appeal and charm derived from the contrast between the two ornamental and austere characteristics of the two styles.[8]

Early on, the neighborhood held a mix of German, Jewish, English and African American residents. In fact, St Mary's German Catholic Church was built on Marshal St to serve the growing German Catholic immigrant community that had moved into the greater Richmond community from about 1850 to through the 1880s.

The center of the neighborhood is dominated by the former Armstrong High School, now the Richmond Public Schools Adult Career Development Center. Armstrong's sports field is now Abner Clay Park, which has a bandstand, football field, basketball court and tennis facilities.

Notable historic churches in Jackson Ward include the Third Street Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Hood Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church, Ebenezer Baptist Church and Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church. Sixth Mount Zion is known as the home of African-American evangelist John Jasper, whose famous "Sun Do Move" sermon brought him fame .

The Leigh Street Armory is now being revitalized and will be the future home of the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia, which was previously located at 00 Clay Street in Jackson Ward.[9]

See also

- Neighborhoods of Richmond, Virginia

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Richmond, Virginia

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Jackson Ward Historic District". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- 1 2 "National Register Nomination" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Jackson Ward HD - 2002 Additional Documentation" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ [http://www.richmondcenter.com

- ↑ "First Battalion Virginia Volunteers Armory". National Park Service. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ The Jackson Ward historic district. Richmond : Dept. of Planning and Community Development. 1978. pp. 27–31.

- ↑ "Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia". Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jackson Ward. |

- Historic Jackson Ward Association

- Historic Richmond Foundation Architecture Survey

- Jackson Ward - Richmond (VA)

- Adult Career Development Center

- Black History Museum

- Black History Sites of Richmond

- First Fridays Artwalk

- Jackson Ward neighbors on Yahoo!Groups

- Jackson Ward on Myspace.com

- Greater Jackson Ward News

- Jackson Ward Historic District Collection from the collection of the VCU Libraries

- Richmond Commission of Architectural Review Slide Collection from the collection of the VCU Libraries

- Richmond Architectural Survey Collection from the collection of the VCU Libraries

- Jackson Ward Historic District, Bounded by Marshall, Fifth, & Gilmer Streets, Richmond, Independent City, VA: 2 photos, 2 color transparencies, and 2 photo caption pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

|

Virginia Union University | Barton Heights; Gilpin |  | |

| Carver | |

Court End | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Fan district | Monroe Ward | Central Business District Virginia State Capitol |