Irish stepdance

| Irish step dance | |

|---|---|

Irish dancers performing at a show | |

| Medium | dance |

| Types | performance and competition |

| Ancestor arts | Irish dance |

| Originating culture | Irish |

| Originating era | mid-1800s to present |

Irish stepdance is a style of performance dance with its roots in traditional Irish dance. It is generally characterized by a stiff upper body and quick and precise movements of the feet. It can be performed solo or by groups. Irish stepdance is performed in most places with large Irish populations. Aside from public dance performances, there are also stepdance competitions all over the world. Costumes are considered important for stage presence in competition and performance Irish stepdance. Riverdance, an Irish stepdancing interval act in the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest that later became a hugely successful theatrical production, greatly contributed to its popularity.

Two types of shoes are worn; hard shoes, which make sounds similar to tap shoes, and soft shoes, which are similar to ballet slippers. The dances for soft shoe and hard shoe are generally different, though they share basic moves and rhythms. Most competitive stepdances are solo dances, though many stepdancers also perform and compete in traditional set and céilí dances. Competition is organized by several organizations, and there are competitions from the local level to world championships. Several other theatrical productions based around Irish stepdance have been made since Riverdance.

Roots

The dancing traditions of Ireland are likely to have grown in tandem with Irish traditional music. Its first roots may have been in Pre-Christian Ireland, but Irish dance was also partially influenced by dance forms on the Continent, especially the quadrille dances. Traveling dancing masters taught all over Ireland beginning around the 1750s and continuing as late as the early 1900s.[1]

Professor Margaret Scanlan, author of Culture and customs of Ireland, points out that the earliest feis or stepdancing competition dates no earlier than 1897, and states: "Although the feis rhetoric suggests that the rules [for international stepdancing competitions] derive from an ancient past, set dances are a product of modern times".[2] There are many styles of stepdancing in Ireland (such as the Connemara style stepdancing), but the style most familiar is the Munster, or southern, form, which has been formalised by An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha (English: The Gaelic Dancing Commission), which first met in 1930. The Commission (abbreviated as CLRG), was formed from a directorate of the Gaelic League that was formed during the Gaelic Revival and codified the modern rules.

In the 19th century, the Irish diaspora had spread Irish dance all over the world, especially to North America and Australia. However, schools and feiseanna were not established until the early 1900s: in America these tended to be created within Irish-American urban communities, notably in Chicago. The first classes in stepdancing were held there by the Philadelphia-born John McNamara.[3]

According to the BBC's A Short History of Irish Dance, "The nature of the Irish dance tradition has changed and adapted over the centuries to accommodate and reflect changing populations and the fusion of new cultures. The history of Irish dancing is as a result a fascinating one. The popular Irish dance stage shows of the past ten years have reinvigorated this cultural art, and today Irish dancing is healthy, vibrant, and enjoyed by people across the globe."[4]

One explanation for the unique habit of keeping the hands and upper body stiff relates to the stage. To get a hard surface to dance on, people would often unhinge doors and lay them on the ground. Since this was clearly a very small "stage," there was no room for arm movement. The solo dances are characterised by quick, intricate movements of the feet.

Sometime in that decade or the one following, a dance teacher had his students compete with arms held firmly down to their sides, hands in fists, to call more attention to the intricacy of the steps. The adjudicator approved by placing the students well. Other teachers and dancers quickly followed the new trend. Movement of the arms is sometimes incorporated into modern Irish stepdance, although this is generally seen as a hybrid and non-traditional addition and is only done in shows and performances, not competitions.

Irish stepdance has precise rules about what one may and may not do, but within these rules leeway is provided for innovation and variety. Thus, stepdance can evolve while still remaining confined within the original rules.

Dances

Irish stepdances can be placed into two categories. Solo stepdances, which are danced by a single dancer, and group stepdances, which are coordinated with 2 or more dancers.

Solo dance

Reel, slip jig, hornpipe, and jig are all types of Irish stepdances and are also types of Irish traditional music. These fall into two broad categories based on the shoes worn: hard shoe and soft shoe dances. Reels, which are in 2

4 or 4

4 time, and slip jigs, which are in 9

8 time and considered to be the lightest and most graceful of the dances, are soft shoe dances.[5][6] Hornpipes, which can be in 2

4 or 4

4 time, are danced in hard shoes. Three jigs are danced in competition; the light jig, the single jig,which is also called the Hop jig, and the treble jig, which is also called double jig. Light and single jigs are in 6

8 time, and are soft shoes dances, while the treble jig is hard shoe, danced in a slow 6

8. The last type of jig is the slip jig, which is danced in 9

8 time. There are many dances, which steps vary between schools. The traditional set dances (danced in hardshoe) like St. Patrick's Day and the Blackbird, among others, are the only dances that all schools have the same steps.

The actual steps in Irish stepdance are usually unique to each school or dance teacher. Steps are developed by Irish dance teachers for students of their school. Each dance is built out of the same basic elements, or steps, but the dance itself is unique, and new dances are being choreographed continuously. For this reason, videotaping of competitions is forbidden under the rules of An Coimisiun.

Each step is a sequence of foot movements, leg movements and leaps, which lasts for 8 bars of music, starting on the right foot. This is then repeated on the left foot to complete the step. Hard shoe dancing includes clicking (striking the heels of the shoes against each other), trebles (the toe of the shoe striking the floor), stamps (the entire foot striking the floor), and an increasing number of complicated combinations of taps from the toes and heels.

There are two types of hard shoe dance, the solo dances, which are the hornpipe and treble jig, and the traditional set dances, also called set dances, which are also solo dances, despite having the same name as the social dances. Traditional set dances use the same choreography regardless of the school whereas contemporary sets are choreographed by the teachers. The music and steps for each traditional set was set down by past dance masters and passed down under An Coimisiún auspices as part of the rich history of stepdancing, hence the "traditional."

There are about 30 traditional sets used in modern stepdance, but the traditional sets performed in most levels of competition are St. Patrick's Day, the Blackbird, Job of Journeywork, Garden of Daisies, King of the Fairies, and Jockey to the Fair. The remaining traditional set dances are primarily danced at championship levels. These tunes vary in tempo to allow for more difficult steps for higher level dancers. An unusual feature of the set dance tune is that many are "crooked", with some of the parts, or sections, of the tunes departing from the common 8 bar formula. The crooked tune may have a part consisting of 7½ bars, fourteen bars, etc. For example, the "St. Patrick's Day" traditional set music consists of an eight-bar "step," followed by a fourteen-bar "set."

Group dance

The group dances are called céilí dances or, in the less formal but common case, figure dances. Competitive céilís are more precise versions of the festive group dances traditionally experienced in social gatherings.

There is a list of 30 céilí dances that have been standardised and published in An Coimisiun's Ár Rinncidhe Foirne[7] as examples of traditional Irish folk dances. Standardized dances for 4, 6 or 8 dancers are also often found in competition. Most traditional céilí dances in competition are significantly shortened in the interests of time. Many stepdancers never learn the entire dance, as they will never dance the later parts of the dance in competition.

Other céilí dances are not standardised. In local competition, figure dances may consist of two or three dancers. These are not traditional book dances and are choreographed as a blend of both traditional céilí dancing and solo dancing. Standardized book dances for 16 dancers are also rarely offered. Figure Choreography competitions held at major oireachtasi (championships) involve more than 8 dancers and are a chance for dance schools to show off novel and intricate group choreography.

Some dance schools recognised by An Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha place as much emphasis on céilí dancing as on solo dancing, meticulously rehearsing the dances as written in the book and striving for perfect interpretation. In competition, figure dancers are expected to dance their routine in perfect unison, forming seamless yet intricate figures based on their positions relative to each other.

Costume

In public performances, dancers wear costumes appropriate to the show. The costumes are frequently modern interpretations of traditional Irish styles of dress. In competitions, there are various rules and traditions which govern the choice of a dancer's costume.

Competitive costumes

Judges at competitions critique the dancers primarily on their performance, but they also take into account presentation. In every level of competition the dancers must wear either hard shoes or soft shoes. Boys and girls wear very distinctive costumes. Girls must wear white poodle socks or black tights. Competition dresses have changed in many ways since Irish Dance first appeared. Several generations ago the appropriate dress was simply your "Sunday Best". In the 1980s ornately embroidered velvet became popular. Other materials include gaberdine and wool. Today many different fabrics are used, including lace, sequins, silk, embroidered organzas and more. Some dresses, mainly solo dresses, have flat backed crystals added for stage appeal. Swarovski is being used more frequently. Velvet is also becoming popular again, but in multiple colours with very different, modern embroidery. The commission dresses have stiff skirts which can be stiffened with Vilene and are intricately embroidered.

Costumes can be simple for the beginning female dancer; they often wear a simple dance skirt and plain blouse or their dancing school's costume. The certain colours and emblem that are used on the dresses represents the dance school to differentiate it from other dance schools. These are similar to a solo dress, but are simple with only a few colours, while are still more pounds, depending on the fabric, and may require some getting used to. School costumes are not decorated with crystals.

At advanced levels where dancers can qualify for Major competitions, solo costumes help each dancer show their sense of style, and enable them to stand out among a crowd. The dancers can have a new solo dress specially tailored for them with their choice of colours, fabrics, and designs. Popular designers include Gavin Doherty, Siopa Rince, and Elevations. Some dancers will even design the dress themselves. The dancer can also buy second hand from another dancer. Since the dresses are handmade with pricey materials, unique designs, and are measured to each dancer's body type, the dresses can cost between $600 and $4,000.

Along with having the handcrafted dresses, championship commission dancers have wigs and crowns or decorative headbands. In commission schools female dancers have the choice to wear either a wig or curl their hair, but usually in championship levels, girls choose to wear a wig, as wigs are more convenient and popular. Dancers get synthetic ringlet wigs that match their hair color or go with an extremely different shade (a blonde dancer wearing a black wig or vice versa). The wigs can range from $20.00 to $150. Usually the crowns match the colours and materials of the dresses, but some dancers choose to wear tiaras, or tiaras with a fabric crown. The championship competitions are usually danced on stages with a lot of lighting. To prevent looking washed out, dancers often wear stage makeup and tan their legs. A rule was put in place in January 2005 for Under 10 dancers forbidding them to wear fake tan, and in October 2005 it was decided that Under 12 dancers who were in the Beginner and Primary levels would not be allowed to wear fake tan or make up.

The boys used to wear jackets and kilts, but now more commonly perform in black trousers with a colorful vest and tie and, more frequently, a vest with embroidery and crystals.

Festival costumes

The festival style differs, styling more towards a simple unified design, not using much detail or diamonds. Irish dance festivals (also called "shows") have dancers wear their hair either in a wig or down, depending on the age and level of the dancer.

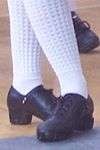

Shoes

Some of the footwork of softshoe dances is echoed in the footwork of Scottish country dancing, though the two styles are distinct. American tap dance was also influenced by Irish Stepdancing.

Three types of shoes are worn in competitive step dancing: hard shoes and two kinds of soft shoe.

Hard shoes

The hard shoe, which is also called heavy shoe and jig shoe, is, unlike tap shoes, made with fiberglass tips, instead of metal. The first hard shoes had wooden taps with metal nails. It was common practice in the 17th and 18th century to hammer nails into the soles of a shoe to increase the life of the shoe. Dancers used the sounds created by the nails to create the rhythms that characterize hard shoe dancing.

Beginning in the 1990s shoes tips were made using resin or fiberglass to reduce the weight and enhance the sound of the footwork. Hard shoes are made of black leather with flexible soles. Sometimes the front taps are filed flat to enable the dancer to stand on his or her toes, somewhat like pointe shoes.

Each shoe has eight striking surfaces: the toe, bottom, and sides of the front tap and the back, bottom, and sides of the back tap (the heel). The same hard shoes are worn by all dancers, regardless of gender or age.

A legend about hard shoe dances is that the Irish used to dance at crossroads or on the earthen floors of their houses, and they removed and soaped their doors to create a resonant surface for hard shoe dancing. The more common actuality was that dancers "battered" on a stone laid in the floor with a space underneath; in the case of set dancing, the head couple of the set would claim the stone.

Soft shoes

Soft shoes, often called "ghillies" fit more like ballet slippers and are made of black leather, with a leather sole and a very flexible body. They lace from toe to ankle and do not make sounds against the dance surface. They are worn by female dancers for the light jig, the reel, the single jig, the slip jig, and group dances with two or more people. They are also worn for competitive céilí dancing, though social céilí dance doesn't have rules about the shoes that can be worn.

The second kind of soft shoe is worn by male dancers; these are called "reel shoes" and are similar to Oxford or jazz shoes in black leather, with fiberglass heels that the dancers can click them together. Some male dancers do not wear fiberglass heels. The men's steps may be choreographed in a different style to girls' to take advantage of the heels and to avoid feminine movements in steps.

Competition structure

Competitive step dancing has grown steadily since the mid 1900s, and more rapidly since the appearance of Riverdance. An organised stepdance competition is referred to as a feis (/ˈfɛʃ/, plural feisanna). The word feis means "festival" in Irish, and strictly speaking is also composed of competitions in music and crafts. Féile ("faila") is a more correct term for the dance competition, but the terms may be used interchangeably. Many annual competitions are truly becoming full-fledged feiseanna, by adding competitions in music, art, baking, etc.

Participants in a feis must be students of an accredited step dance teacher. Dance competitions are divided by age and level of expertise. The names for feis competition levels vary around the world:

- UK and Europe: beginner, primary, intermediate, open[8]

- Ireland: Bun Grád, Tús Grád, Meán Grád, Ard Grád, Craobh Grád (translates as "bottom", "beginning", "middle", "high" and "trophy" grades)[8]

- North America: Beginner, Advanced Beginner (or Beginner 2), Novice, Open Prizewinner, Preliminary Champion, Open Champion (Pre-Beginner is also available for dancers under 6. At this level, every competitor receives first place.)[8]

- Australia: Novice, Beginner, Primary, Intermediate, Open[8]

- South Africa: Bun Grád, Tús Grád, Meán Grád, Ard Grád, Craobh Grád (Ungraded section is also offered for dancers 7 years old or younger. Dancers who win this section do not grade.)[8]

Teachers must be certified with one of several separate organisations including, but not limited to An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha ("The Irish Dancing Commission or CLRG"),[9] Comhdháil Múinteoirí Na Rincí Gaelacha ("The Congress of Irish Dancing Teachers"),[10] NAIDF ("North American Irish Dance Federation")[11] or World Irish Dance Association (WIDA),[12] in order for their students to be eligible for competitions. Dancers may only enter competitions run by the organisation the teacher is registered with the exception of WIDA feisanna, which are open to everybody. Other less well known organisations also exist.[13]

Each organisation has a certification process which consists of a written and practical exam in the applicant's ability to teach Irish dance. In An Coimisiún these certificates are the T.M.R.F. (gives permission to teach céilí dances), T.C.R.G. (gives permission to teach solo dances) and A.D.C.R.G. (gives permission to judge at feisanna).

Despite a competition structure and culture that almost exclusively supports children, many feisanna offer competitions for adult Irish dancers. A beginner dancer can be any age, including adults. A beginner adult Irish stepdancer is someone who did not dance as a child and is over the age of 18. Past beginner level, there is no restriction. Adult competitions, when offered, are held separately from children's competitions, and adults may advance only to Prizewinner level in North America. If they wish to attempt higher levels, then they must switch over to competitions for young adults and may no longer compete as "Adults." This is referred to an "And Over" level, such as Ages 18 and Over.

In North America, the Irish Dance Teachers Association of North America has recently changed its rules to restrict adult Irish dancers to the simpler, traditional speed hardshoe dances. Adult dancers capable of dancing the more complex, non-traditional speed hardshoe dances must have the support of their teacher before they can compete in the "And Over" age categories where they may perform the more complex dances.[14]

Rules for feisanna are set by the Organization, not a particular feis. In An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha (the largest of the "official" organisations), dancers are judged by adjudicators certified by An Coimisiún. This certification is known as the A.D.C.R.G., meaning Árd Diploma Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha (in English – Highest Diploma in Gaelic Dancing.) It is awarded to those who have passed the exams set by the An Coimisiún and have also been certified as T.C.R.G. Local organisations may add additional rules to the basic rule set. The Irish Dance Teacher's Association of North America (IDTANA) is the largest body of dance teachers associated with An Coimsiun le Rince Gaelacha. There are seven CLRG regions in North America.

An annual regional championship competition is known as an oireachtas /ˈɪərəxtəs/. Regional Oireachtas are normally held in November and December. Up to 10 dancers from each age group may qualify for the World Championships. The exact number is worked out with a formula and is based on the number of dancers competing. National championship competitions are held annually in Ireland, North America, the UK, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe. An Coimisiún's annual World Championship competitions (Irish: Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne) began in 1970 and have been held in the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and more recently in the United States (2009, 2013), England (2014) and Canada (2015). Past and future host cities of the World Championships include:

- 1970: Dublin

- 1975: Dublin

- 1980: Ennis

- 1981: Dún Laoghaire

- 1983: Dublin

- 1985: Malahide

- 1986: Limerick

- 1987: Galway

- 1988: Galway

- 1989: Galway

- 1990: Galway

- 1994: Dublin

- 1995: Galway

- 1996: Dublin

- 1997: Galway

- 1998: Ennis

- 1999: Ennis

- 2000: Belfast

- 2001: Cancelled due to Foot-and-mouth outbreak

- 2002: Glasgow

- 2003: Killarney

- 2004: Belfast

- 2005: Ennis

- 2006: Belfast

- 2007: Glasgow

- 2008: Belfast

- 2009: Philadelphia

- 2010: Glasgow

- 2011: Dublin

- 2012: Belfast

- 2013: Boston

- 2014: London

- 2015: Montreal

- 2016: Glasgow

In the media

Riverdance was the interval act in the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest which contributed to the popularity of Irish stepdance, and is still considered a significant watershed in Irish culture.[15] Its roots are in a three-part suite of baroque-influenced traditional music called "Timedance" composed, recorded and performed for the 1994 contest, which was hosted in Ireland. This first performance featured American-born Irish dancing champions Jean Butler and Michael Flatley, the RTÉ Concert Orchestra and the Celtic choral group Anúna with a score written by Bill Whelan. Riverdance's success includes an eight-week sell out season at Radio City Music Hall, New York, with the sales of merchandise resulting in Radio City Music Hall merchandise sale's record smashed during the first performance, sell-out tours at King's Hall, Belfast, Northern Ireland, and The Green Glens Arena, Millstreet, Co. Cork, Ireland, plus a huge three and a half-month return to The Apollo in Hammersmith with astounding advance ticket sales of over five million pounds.

After Flatley left Riverdance, he created other Irish dance shows including Lord of the Dance, Celtic Tiger Live and Feet of Flames, the last-named being an expansion of Lord of the Dance.

In 2011 a documentary was released titled Jig. It follows Irish dancers as they prepare for the World Championships in March 2010. TLC acquired the rights to the documentary in preparation for a new television show about the competitive Irish stepdance world in America, for which the working title is Irish Dancing Tweens. The series, which will be produced by Sirens Media, features several dance schools. Each episode will focus on individual dancers during rehearsals, preparation, travel, and during competitions. Eight episodes of the series have been ordered.[16][17]

See also

References

- ↑ Don Haurin & Ann Richens (February 1996). "Irish Step Dancing – A Brief History". Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Scanlan, 2006: p. 162.

- ↑ Long, Lucy. "Irish Dance" in The American Midwest: an interpretive encyclopedia: p. 389

- ↑ "A Short History of Irish Dance." BBC News. BBC, n.d. Web. 25 Feb 2013. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/irish/articles/view/741/english/>.

- ↑ Megan Romer. "Reel". Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Megan Romer. "Jig". Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ AR RINNCIDHE FOIRNE – THIRTY POPULAR FIGURE DANCES, VOLS. 1–3 (09-76) – Elderly Instruments

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Competition". Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ An Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha

- ↑ http://www.irishdancingorg.com/comh/

- ↑ North American Irish Dance Federation, LLC (NAIDF)

- ↑ Welcome to the World Irish Dance Association

- ↑ "Associations".

- ↑ "Irish Dance Teachers Association of North America".

- ↑ O'Cinneide, Barra. The Riverdance Phenomenon. Blackhall Publishing.

- ↑ Hunter Lopez, Lindsey. "TLC orders 'Irish Dancing Tweens'".

- ↑ Nededog, Jethro. "TLC Pairs Up With Competitive Irish Dancers on New Series (Exclusive)".